Years later, she wrote, “This is how mercy moves through a war. Not in speeches, not in orders, but in tired men refusing to leave strangers in the snow.”

By the time the storm blew itself out, the road to the ridge was lined with stalled trucks and drifts as high as a man’s chest. Patrols went out to find the lagging squad Harris had sent behind the column, half expecting to find frozen shapes in ditches. Instead they found them in and around that farmhouse.

The place had become a small, improvised sanctuary.

Inside, every bed and bench was full. American soldiers lay with their boots off, feet swaddled in bandages or wool socks, steam rising from wet clothes hung over chairs. On the floor near the stove, the German women sat wrapped in the same brown army blankets as the men, hands curled around tin cups of soup. Paula’s toes were wrapped in gauze. Diaz had painted them with something that burned and then soothed.

No one cared much about uniforms in that room.

A medic moved from pallet to pallet, checking frostbitten fingers with the same professional touch, regardless of what language the patient spoke. A corporal from Ohio dozed against the wall, his head tipped back, while a woman from Bremen—who had manned radios in a concrete tower for months—slept with her head on his arm, snoring softly.

When Harris ducked into the doorway, shaking snow from his helmet, the smell of wood smoke and boiled potatoes hit him first. Then the sight.

“You made it,” he said.

Miller, sitting on an upturned crate with his boots off and a blanket around his shoulders, grinned tiredly. “You said no one dies in a ditch, sir. We found a house.”

It wasn’t heroism in the storybook sense. No one had charged a machine-gun nest. No medals would be written up for carrying frozen enemy auxiliaries six miles through a blizzard. Officially, the report that went up the chain of command would read something like: “Twelve female POWs evacuated to aid station. No casualties.”

But for the women, it was the hinge on which their idea of “enemy” swung.

The war went on without consulting them.

Within weeks, the American advance rolled over the ridge they had struggled to reach. Towns fell. Bridges were crossed. In April, the Rhine was behind the U.S. First Army. By May, Germany had surrendered. The maps in headquarters were redrawn, lines vanishing and borders shifting.

For Paula and the other women, those months blurred into a series of waypoints: the farmhouse turned temporary aid station; a proper field hospital farther back, where a German-speaking nurse laughed at their astonishment at clean sheets; then a rail siding stacked with repurposed freight cars; then a camp with straight rows of barracks and barbed wire fences somewhere in France.

There, the routines of captivity wrapped around them. Roll calls, work details, medical inspections. For a time, they were numbers on lists: Prisoner No. 84712, No. 84713, No. 84714. But behind the numbers, some moments stayed sharp.

One evening, months later, Paula saw a familiar face at a distance—a jawline under a helmet, a way of walking. It took her a second to recognize him without snow blowing sideways across his cheeks.

Sergeant Miller spotted her at the same moment.

He raised a hand.

“Hey, Paula, right?” he called through the fence, sure he was mangling the name.

She nodded, pressing fingers through the wire.

He mimed hoisting something on his back and staggered comically, rolling his eyes as if to say, you nearly killed me that day. She laughed, an honest, surprised sound that made a nearby guard glance over and then look away again, smiling faintly to himself.

They never had much language in common—his German stopped at a few phrases, her English was barely forming—but they didn’t need words to understand the shared memory of cold and weight and the knowledge that each had, in a way, kept the other alive.

After the war ended, trains and ships carried the women back east through a Germany that looked more like a wound than a country. Paula stepped off in a town she barely recognized. The school where she had once written essays in careful script was a shell. The church spire lay broken across the market square. Her parents’ house was gone, a pit of blackened bricks and tangled beams.

It was, in some ways, easier to talk about physical losses than about what had happened in that cellar and on that road.

In the first years after the war, few wanted to hear about Americans sharing blankets in a storm. People spoke instead of hunger winters, of missing sons, of occupation indignities. To say “we were treated well by them” felt like disloyalty, or at least like rubbing salt into a wound that still bled.

So Paula held the story close. She married, had children. She queued for ration cards, cleared rubble, stitched worn clothes to make them last another year. At night, when winter winds rattled their new windows, she sometimes dreamed of the howl over the Eiffel Hills and the sensation of being lifted, weightless for an instant, in arms that were supposed to harm.

Years later, when her son came home from school with questions—Why did we lose? What were the Americans like?—she found that the story wanted to be told.

She didn’t start with Hitler, or battles, or speeches. She started with the cold.

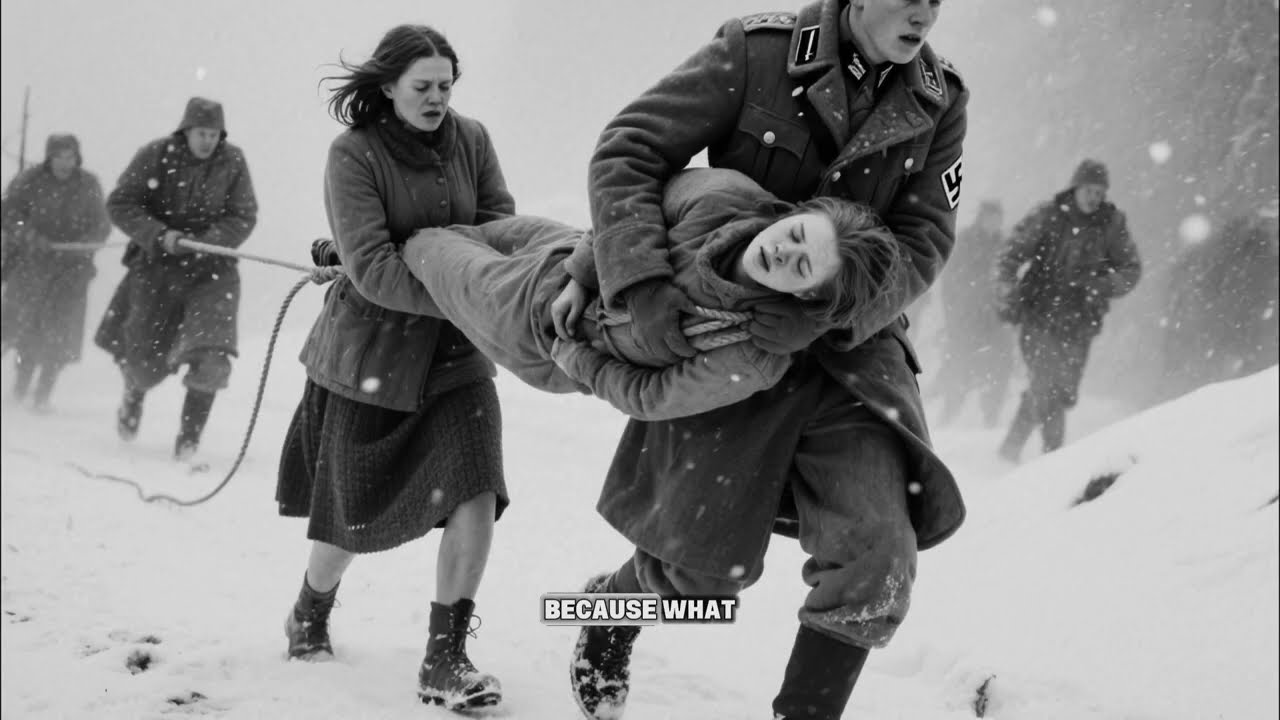

She described the cellar that smelled of smoke and fear. The long march through snow with boots that had given up. The cellar door opening on light and strange faces. The American medic’s hand on her foot, warmer than anything she’d felt in days. The argument in the street, where she didn’t understand the words but understood the stakes. The rope around her waist. The weight of another woman’s arm over her shoulder. The farmhouse. The soup.

“They had orders,” she told her son. “Orders to leave and save themselves. And they had a chance to leave us. No one would have known our names. We were the enemy. But they stayed with us. They carried us. That… changes something.”

Her son frowned, trying to fit that into the simpler narratives he’d heard elsewhere.

“I thought they were all…” he searched for the right word, “…victors. Hard.”

“Some were,” she said. “War makes people hard. But some made space inside their hardness for other choices.”

When her grandchildren, decades later, studied the war in school, the maps in their textbooks showed arrows and fronts and casualty figures. The Battle of the Bulge was a paragraph, maybe two. They came to visit on a winter day and complained about the cold walk from the bus.

“You weren’t there,” she told them with a small smile, “when the snow tried to steal your breath.”

They laughed, but then she began talking quietly about 1945.

She told them about twelve women in a cellar who thought “enemy” meant one thing, and a handful of American soldiers in the snow who showed them it could mean something else. Not “friend”—that would come much later with time and letters and exchange visits for some people—but something like “fellow human, subject to the same cold.”

Sergeant Tom Miller went back to the States in 1946. He returned to a hardware store job in Ohio, a wife who’d learned to run a household without him, and a son who had been born while he was in France. Sometimes in winter, when the wind came whistling across the flat fields and piled snow against the porch, he would stand at the window and watch the white blur and feel an old rope dig into his waist.

When his own grandchildren asked him about the war, he didn’t talk first about firefights or medals. He talked about tripping over roots in the dark with another human being slung over his shoulders, numb fingers refusing to let go.

“I didn’t want to come home and have to live with the idea that I’d left somebody to freeze because my orders told me to walk faster,” he told his daughter once. “That ain’t the kind of soldier I wanted to be. That ain’t the kind of man I wanted you to think I was.”

He never saw Paula again.

He didn’t need to.

He trusted, in the way he had learned to trust in the war, that the effort had not ended in that farmhouse. That she had gone on carrying something intangible that weighed nothing and everything.

History books will always show the big things: the dates, the battles, the lines on maps that shift like shadows. They’ll tell you that the winter of 1944–45 was a season of offensives and counteroffensives, of the Bulge and the crossing of the Rhine.

They rarely mention what happened on that one snow-choked road in the Eiffel Hills, when a lieutenant, a sergeant, and a handful of cold, tired men decided that the loudest voice in their heads would not be the one saying “Move on.”

In that moment, the machinery of war—the orders, the timetables, the fuel calculations—met something older and quieter: the unwillingness to let people die simply because it was easier.

Twelve German women walked into that blizzard expecting to be abandoned by the enemy their own leaders had taught them to fear.

They came out of it with frostbitten toes, US Army blankets, and a new, unsettled knowledge: that the world was more complicated than the slogans that had been fed to them. That mercy could come from the direction they’d been taught to dread.

Paula put it best, many years later, when a young historian asked her what she had learned from that night.

“I learned,” she said, “that sometimes the enemy is not the man in front of you. It is the idea in your own head that says his suffering does not matter. Those Americans refused that idea. They gave me back my life. And they gave me back a piece of my humanity I might otherwise have lost.”

On a frozen road in 1945, under a sky that wanted to kill everyone equally, a group of soldiers carried their enemies through a storm.

They had no reason to believe anyone would remember.

But we do.

News

For almost 2 years, I sat across white tablecloths watching my boss slice people up with words sharper than any knife, telling myself it was just part of working for a powerful CEO.

“If you spill one drop on this dress, you’ll pay for it.” That was the first thing my boss said…

Poor Black Nanny Adopted 3 Boys Nobody Wanted— 25 Years Later, They Did the Unthinkable

The day three black cars pulled up outside my mother’s crumbling brick house, the neighbors thought someone had died. I…

At 16, My Dad Disowned Me For My Brother’s Lie. “You’re A Disgrace,” He Yelled. Two Weeks Later, His Pride Shattered When He Found Out The Truth.

“You’re not welcome in this house if you act like this.” My dad’s voice cut through the rain harder than…

For 5 years I packed sad little Tupperware lunches, worked late nights, and funneled every bonus and spare dollar into a savings account with one goal: a place that was finally mine.

“The house belongs to your sister.” My dad said it so calmly that for a second I thought I’d misheard…

Millionaire Invited Black Cleaning Lady to Mock Her… But She Arrived Like a Diva and Left Them in Shock

The invitation arrived on a Tuesday, folded in on itself like it knew it had no business coming through the…

“A millionaire returns unexpectedly to find his maid tied up next to his twins… and the ending is shocking…

By the time Elena’s arms began to shake, she couldn’t tell whether it was from exhaustion or fear. The twins…

End of content

No more pages to load