The sun rose hard and white over central Texas, flattening everything beneath it into glare and dust.

July 4th, 1945. Camp Swift.

By midmorning the recreation field was already shimmering. Heat fanned up off the hard-packed ground, carrying the smoke from the long row of grills until it hung over the camp in a blue haze. Somewhere a brass band was tuning up, brass notes bending in the dry air.

On the far side of the field, two squads of German women marched in step, boots crunching on gravel.

There were only about thirty of them in all, nothing compared to the thousands of male prisoners scattered across Camp Swift’s 18,000 acres. From a distance they might have been any group of women on a factory outing—cotton dresses instead of uniforms now, hair tied back with strips of cloth or army-issue combs. Up close, the story was written clearer: collarbones sharp, eyes set deep in faces that had seen too many sirens and too little sleep.

At the head of the file walked twenty-four-year-old Leisel Weber, once a secretary in Cologne, later a communications helper in Hitler’s Luftwaffe. She kept her gaze straight ahead, not because the Americans demanded it, but because the smells floating on the wind made her dizzy.

Roasting meat. Coffee. Something sweet and sharp—vinegar and mustard.

Behind her, Hilda, a nurse from Dortmund, whispered in German, voice so low it barely moved the air. “They must be mad to burn so much fat in this heat.”

“Maybe they want us to salivate,” someone muttered. “Makes it easier to laugh when they take it away.”

No one laughed. Fear had been their reflex for too long.

They had been told since girlhood that Americans were crude, violent, undisciplined. In Nazi newsreels, Yankee soldiers were slouching figures in ill-fitting uniforms, eyes blank with stupidity or burning with hunger. The Party had warned them: if the Americans ever set foot on German soil, German women would suffer most. Hair shorn, bodies violated, food withheld.

Even after two months in Texas, there were parts of those warnings that clung in the dark corners of their minds.

The guards flanking them were young men in sun-faded uniforms, rifles held more like habits than weapons. One—a boy from Iowa with hair the same color as the dust—caught Leisel glancing toward the grills and gave her a quick, lopsided smile that he probably thought she didn’t see.

The Lieutenant leading them halted at the edge of the field. The women fell out in a loose knot in the shade of the bleachers, if you could call that strip of slightly lighter ground “shade.” The sergeant in charge stepped forward.

“Food first,” he said in careful German, courtesy of a German-American interpreter from Dallas. “Then music and games. No trouble. Understand?”

Heads nodded.

Food first.

Two months earlier, the idea would have been unthinkable.

Back then, the women had been standing in a muddy field in northern France, hands raised, Luftwaffe grey hanging off their frames like someone else’s lives.

The front had collapsed so fast there hadn’t even really been an order. One day they were routing messages and scribbling down coordinates in a school requisitioned for signals. The next, their officers had vanished, the radios were silent, and the men who remained were only interested in burning papers and finding civilian clothes.

“Do not let the Americans take you,” their last Feldwebel had told them. He’d said it over the chatter of a burning file cabinet. “They’re animals. They’ll shame you, starve you. Better to run east—even to the Russians—than fall into their hands.”

Then he’d pulled on a worn brown coat over his uniform and slipped away like smoke.

There hadn’t really been a choice. The Red Army was still far away; the Americans were already on the road.

So when a patrol in olive drab rounded the corner of that French lane and shouted in English, the women in Luftwaffe grey lifted their arms and tried not to make eye contact.

The first shock was that none of the Americans fired.

“Hands up, ja,” one of them said in mangled German. “Langsam… slowly.”

They knew the taste of fear in their mouths, the chalk of it. They shuffled forward.

Up close, the soldiers didn’t look like the monsters of the newsreels. They looked like tired young men in dirty uniforms, faces smeared with dust and sweat, eyes red from lack of sleep. One of them had freckles. Another had a gap between his teeth. One, with an accent that rolled like the Rhine valley, asked, “Name?” with the easy German he’d learned from his grandmother.

They were separated from male prisoners, counted, searched for weapons. They waited for blows that didn’t come.

Then someone shouted, “Mess truck’s here!” and the smell hit them.

Coffee.

Not the bitter burnt acorn substitute they’d been drinking since 1941, but real coffee. Rich, dark, strong. Behind it came the warm, greasy smell of stew. Potato. Some kind of meat.

They stared at the clanking field kitchen as if it were an alien machine.

“Get ’em fed,” a sergeant said, nodding at the women. “POWs get chow same as anybody. Orders from way up.”

Metal trays were pushed into hands that still expected fists. A ladle dropped stew onto each one, thick with recognizable chunks. A whole boiled potato followed. Then a slice of bread — soft, white bread that sprang back when you pressed it.

Leisel pressed her thumb into hers. It left a neat depression.

Back home, bread had been black and dense for years, bulked out with ground beet, barley husks, and whatever the mills could legally—and illegally—add. It crumbled when you tried to spread anything on it. It tasted mostly of sawdust and salt.

She raised the white bread to her nose. It smelled of yeast. Of the bakery on the corner of their street in Cologne before the war. The bakery that was now a roped-off crater.

“We expected blows and hunger,” Hilda whispered. “Instead they hand us this.”

That night, in the stifling press of the makeshift French cage, lying on damp grass with a blanket barely thicker than paper, the stew and bread sat warm in their stomachs. It was the first time in months the gnawing emptiness had softened, even a little.

“If this is how they treat enemies,” Hilda murmured, “what must life be like for their own people?”

It was a dangerous question. They did not yet have anywhere to put the answer.

The ship that carried them west was a Liberty ship. They didn’t know that term, then. To them it was just a hulking grey vessel with rust streaks and a maw that swallowed trucks and bodies and everything that the war turned into cargo.

They were herded down into a hold that smelled of oil and old salt and metal. triple-tier bunks stretched in two rows. She climbed to a middle bunk, feeling the steel frame through the thin mattress. Above her, someone’s booted feet swung. Below her, someone whispered a prayer.

The Atlantic was rough in late May. The ship rolled and pitched. Five women were seasick before they left sight of land and did not really stop until they were halfway across. The air in the hold grew thick and sour, no matter how many times the staff opened the hatches.

But three times a day the mess call sounded, and they lined up and climbed out into the open air.

More white bread. More stew. Once, on a Sunday, two boiled eggs each, their shells still faintly warm. A luxury. Twelve women pooled their eggs, mashed them with a tiny packet of salt someone had begged from a sympathetic guard, and ate in silence with their eyes closed.

One night under the dim red lamp in the hold, Hilda said, “Think of how far this food has traveled. The eggs, the flour, the meat. They came from the other side of an ocean.”

“And from another world,” someone added.

Newport News, Virginia.

The gangplank thudded under boots. They stepped out of the stale air of the hold and into a different world. Cranes swung overhead, lifting crates the size of small houses. Trucks queued along rails that gleamed under the sunlight. Grain elevators stood undamaged. Warehouses had all four walls.

Leisel blinked. The last German port she had seen had been a skeleton of concrete and twisted beams.

The smell was different too. Harbor mud and coal smoke, of course, but threaded through with the sweeter, warmer scent of roasting coffee from a plant somewhere along the docks. People walked along the pier carrying paperwork and lunch pails. Civilians. In clean clothes. No holes, no patches.

It felt like stepping into one of those newsreels the Propaganda Ministry had called lies. Only this time she could not look away from the sharpness of the details. The cracking of a crane pin, the call of a gull, the subtle sheen of fresh paint on the hull of another ship.

They were marched into passenger rail cars, not freight wagons. The seats were upholstered, if worn. The windows had glass. Through them, the country flowed past: fields that went on forever, barns as big as houses, roads with cars on them. Petrol stations with signs that said “GAS” in big friendly letters.

In the barracks nights, the women whispered to each other about it.

“All that,” Hilda said, gesturing toward where the tracks had been, “and we were told they were starving.”

Camp Swift rolled into view as a patchwork of long low buildings, towers, and dust.

Guard towers stood at the corners, their silhouettes sharp against the sky. Double rows of barbed wire framed the roads. Military trucks and jeeps moved in steady lines.

But inside the wire, there were lawns.

Not lush carpets like the parks in Cologne, but grass. Scruffy, sunburned Texas grass, cut short. There were trees, too—a few scattered oaks and hackberries providing a little shade. Someone had planted flowers in a rectangle of dirt ringed by stones: pansies, bravely trying to do their thing against the heat.

Their first barracks smelled of wood, soap, and faintly of the American disinfectant that stung the nose. Two rows of metal bunks. Thin mattresses, yes, but mattresses. A pot-bellied stove at one end. Windows with screens. Air moving.

“This is prison,” someone said. “The Reich never gave us this much when we were free.”

The rules came next.

Twice-daily roll calls. No leaving the compound without permission. Work assignments. No fraternization with male prisoners. They were told, through the interpreter, that the rules were for everyone’s safety. Disobedience would bring loss of privileges, perhaps solitary, but not beatings.

Discipline without blows.

They didn’t quite believe that yet.

Then came the first breakfast.

Oatmeal thick in the bowl. White bread. Coffee.

Real coffee.

Hilda took a sip and closed her eyes. “If I died right now,” she said, “I would still believe this day was worth living.”

Life settled into a rhythm so steady that days blurred.

Bugle at 5:30. Dunkel, dunkel, up.

Washing in long trough sinks, the water sometimes icy, sometimes lukewarm. Work parties marched out under armed escort. Some went to the camp laundry, steam and soap and the slap of wet cloth. Others to the kitchens and potato peeling that made hands ache. A handful to the hospital to mop floors and strip beds. A few, the German women, were kept inside the compound mostly, assigned to sewing, mending, light cleaning.

Lunchtime meant more stew, sometimes beans, sometimes canned plain meat, always bread. “American Army standard rations,” the interpreter explained. “They try to give you similar calories. Geneva Convention.”

Numbers were starting to mean things to them now. Three thousand calories a day, roughly. Twice what their families back home were reportedly living on.

At night, under the glare of the floodlights, they sat on their barracks steps and smoked American cigarettes—Lucky Strikes or Camels acquired with canteen coupons from work pay. They watched the male prisoners play soccer in the central yard. They listened to the faint strains of a guitar from somewhere near the American barracks.

They talked.

“Do you think they’re pretending?” one woman asked. “Like they did with that film they made about our Winter Relief? All for the camera?”

“Have you seen cameras?” Hilda countered.

“No.”

“Then maybe this is just how they are.”

The notice about the Fourth of July went up at the end of June.

It was a single sheet of paper, tacked crookedly to the barracks bulletin board. The top half was in English. The bottom was in German.

“Independence Day Celebration – July 4th

Recreation Field – All Personnel and Authorized Prisoners

Program: Music, Sports, Special Meal”

“National holiday,” the interpreter explained. “Like your May Day was. Music. Games. Food.”

“Food?” Greta asked, voice thin with hope and cynicism.

“Special food,” he confirmed. “Hot dogs. Hamburgers. Watermelon, maybe. It is… tradition.”

Hot dogs. The word dog caught in some throats. A few muttered jokes about what meat exactly went into them. Still, the scent that started to drift over the fence on July 3rd when the cooks tested the grills silenced even the dark humor.

Charcoal. Fat. Something almost like what used to drift from festival stalls back home in the days before everything turned gray.

In the dark that night, with the barracks creaking softly around them, Hilda whispered from the bunk above, “If they feed us the same way they feed themselves on their biggest holiday, then I will believe this country is not what we were told.”

“And if they don’t?” Leisel whispered back.

“Then at least we got to smell it.”

July 4th dawned like any other Texas day: brutally.

The field was a busy chaos of color and motion. American soldiers in khaki and olive drab milled around, some in T-shirts, some with sleeves rolled up, all seeming less tense than the women had ever seen them. Flags hung from poles. The band, their brass instruments catching the sun, launched into a tune that the interpreter said was called “Yankee Doodle.”

The women were lined up and marched out, every step bringing them closer to the row of grills.

It felt like walking into another country inside the fence.

The cooks looked like cooks everywhere—sweating, shouting, joking. They worked fast, assembly-line efficiency born in mess halls and kitchens across a continent. One man shoveled charcoal, another turned sausages, another split buns and laid them open. A fourth man, with forearms the size of hams, wielded two bottles—bright yellow and ketchup red—like paintbrushes.

Leisel reached the front of the line, tray in hand, and froze.

The sausage nestled in the bun, glistening with juices. The mustard and ketchup pooled and dripped in unashamed color. The potato salad on the tray beside it was pale and creamy, flecked with green. The slice of watermelon looked like a jewel, red and black and green all at once.

“Hot dog,” the cook said with a grin. “Very American.” He pointed from the sausage to her, pantomimed eating. “Good. Eat.”

She searched his face for mockery. Found only heat and a sort of weary amusement.

Her hands did the rest.

The first bite was a shock of textures. Soft, then firm, then a burst of hot, salty fat. The mustard cut through it with acid, the ketchup with sugar.

Happy food, she thought, stunned.

The second bite went down easier. By the third, she understood at last why Americans in newsreels seemed so casual about their meals. When your world held this as a simple lunch option, you did not live in fear of tomorrow’s ration.

Around her, other women were discovering the same thing in their own ways.

“This is what they eat on holidays,” Hilda murmured. “We were told they had bread lines and soup kitchens still. We have been living on turnips and lies.”

A private from somewhere down South leaned on his rifle and watched them with curious eyes. “Ain’t much,” he said to no one in particular. “Just a hot dog. But you’d think we were handin’ out miracles.”

Maybe they were.

That afternoon, full for the first time in years, the women sat under the bleachers and watched baseball.

The game itself was incomprehensible. Men ran in circles and sometimes cheered when they failed to hit the ball and sometimes groaned when they did. The American prisoners explained it with a mixture of gestures and broken German. It didn’t really matter.

What mattered was the way the Americans shouted at each other and at their own officers without fear; the way a captain could fumble a catch and be laughed at by his men and laugh back. The way arguments about a close call ended in handshakes, not arrests.

Later, in the classroom, the women would learn the words for it: freedom of speech, accountability, rule of law.

On the Fourth of July, they saw it live, in dust and sweat and laughter.

Going home was harder.

In late winter, the order came. Their names were read out in the icy morning, breath showing white in the air.

Repatriation.

Such a big word for such a scary thing.

They had spent almost a year behind American wire. They had bathed more regularly than some had in their adult lives. They had eaten cafe coffee, hot dogs, peanut butter, canned milk. They had learned English words for things they had thought were out of reach forever.

Now they were going back to a land of ruins and hunger.

The last weeks in camp were bittersweet. They said goodbye to Mrs. Peterson in the little classroom that had smelled of chalk and hope.

“Remember,” she told them, squeezing each hand in turn. “You saw it with your own eyes. We’re not what your teachers told you. You are not what our posters said either. You’re more than uniforms. So are we.”

They lined up one last time for evening chow. The cooks gave them slightly larger portions without comment. A supply sergeant looked the other way when a few tucked extra bread into their coats.

On the day of departure, they carried suitcases that had been gifts from the Red Cross, American wool coats, notebooks, and one more hot dog each, wrapped in wax paper—the quartermaster’s quiet indulgence.

“You’ll get sick of ’em over there,” one GI joked. “Then you’ll see we ain’t so special.”

Leisel bit into hers on the train and tasted Texas sun and charcoal and a kind of reckless generosity she’d never associate with the word “enemy” again.

Germany in 1946 was grey.

Grey sky, grey rubble, grey faces.

The port where they docked was a broken mirror of Newport News—same cranes, same water, but half the buildings were missing pieces, as if a giant hand had taken bites out of them. The air smelled of coal dust and wet ash.

At the reception center, British and German officials processed them, stamped papers, asked questions. There was no band. No grills. The only smell was boiled cabbage.

Homecoming meant standing in line for ration cards.

It meant walking past lots that had once held houses and now held only piles of bricks where kids played among burned-out bathtubs and twisted bed frames. It meant making your way to what had been your street and finding a crater.

For months, maybe years, people resented them.

“You had it easy,” someone snapped when Hilda mentioned Texas. “Eating American meat while your mother stood in line for hours for margarine.”

Hilda never denied it. She never pretended her captivity had been hardship compared to those who’d suffered under bombs and hunger at home.

But she also wouldn’t let the story be twisted.

“Yes,” she said. “I ate American meat. And learned that other nations can treat even their enemies according to laws. Learned that not all of our enemies are monsters. That matters now.”

That was why the Americans had fed them like that. Not out of pure kindness, not because their soldiers were saints, but because someone “way up,” as the sergeant had said, had decided that the way you treat the defeated says more about your system than any speech.

They had come as—and for—a conquering army.

They left as students.

Years later, when West Germany held elections without intimidation, when newspapers criticized chancellors without fear of brown shirts, when people gathered in gardens behind little houses they’d built through sweat and Marshall Plan money, those quiet stories from behind American fences and at American grills mattered.

They were not the whole explanation. History is never that simple.

But they were a part of it.

Somewhere in that explanation is a field in Texas, a girl from Cologne holding a hot dog with trembling hands, and a young lieutenant from San Antonio deciding that on his country’s birthday, the right thing to do was to say “Essen, bitte” instead of “Hands up.”

For the rest of her life, whenever Leisel smelled charcoal on a hot day or someone handed her a sausage in a soft white bun, she would remember that moment.

Not because the sausage itself was so extraordinary—though it had tasted that way at the time—but because of what it quietly declared:

That real strength can afford to be generous.

That the way you win the peace is different from the way you win the war.

And that sometimes, the thing that cracks a wall of hatred is not a bomb or an argument, but a plate held out across a line that used to be a front, and the words:

“Here. This is for you too.”

News

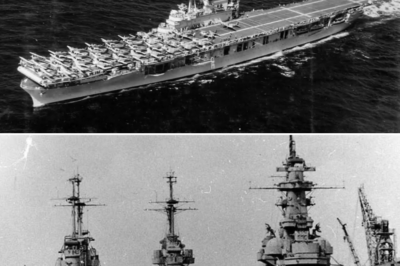

(CH1) Captured German Officers See a US Aircraft Carrier for the First Time

The first time they heard about the American carriers, most of the officers in the Kriegsmarine laughed. It was early…

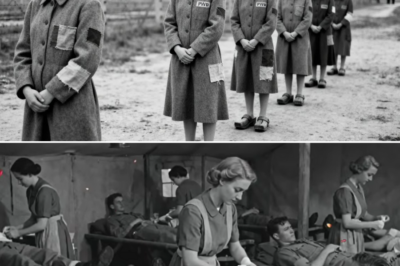

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

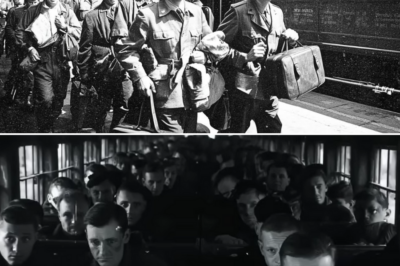

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) He Taught His Grandson to Hate Americans — Then an American Saved the Boy’s Life

January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed. In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul…

End of content

No more pages to load