Part 1

April 15th, 1945. Northern Germany.

The British 11th Armored Division wasn’t looking for a smell.

They were looking for the enemy.

That’s what you do in the last weeks of a war—push forward, clear woods, take villages, keep moving. You expect small-arms fire from a hedgerow, a panicked rear-guard stand, maybe a few desperate men in gray trying to slow you down long enough to vanish north.

But that morning, in the woods, the tanks picked up something else.

A stench.

Not “bad hygiene” stench. Not “dead livestock” stench. Something heavier, thicker, so powerful it seemed to coat the inside of your throat.

The crews tied handkerchiefs around their faces. Some soaked them in water first, like that would help.

It didn’t.

The smell didn’t belong to ordinary war.

It smelled like the end of the world.

They followed it anyway, because soldiers learn fast that the worst things are usually located exactly where your instincts tell you to turn away.

The trees thinned.

A fence line appeared.

Then a gate.

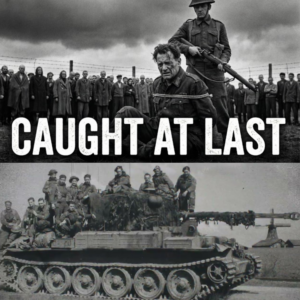

And then, standing there as if he’d been waiting for an appointment, was a man in an immaculate SS uniform.

Boots polished.

Medals shining.

Healthy.

Well-fed.

Arrogant in the way only someone can be arrogant when they believe the world still owes them respect.

He held a riding crop in his hand.

He didn’t run.

He didn’t hide.

He walked up to the lead British tank, raised his arm, and saluted like this was a formal inspection.

And in heavily accented English, he said:

“I am the commandant. I demand a truce. The prisoners are sick. You must not let them out.”

For a moment, the British soldiers stared at him.

Then they looked past him.

And the world behind that gate hit them like a punch.

Bodies stacked like firewood.

Thousands of people moving like shadows.

Living skeletons behind wire, staring with eyes too large for their faces.

A silence so unnatural it made the hair on your arms lift, because silence at that scale doesn’t mean peace.

It means people don’t have the energy to scream anymore.

The British commander—Brigadier Glenn Hughes—stood there looking at the fat, healthy Nazi at the gate and then looking at the nightmare behind him.

His hand went to his revolver.

He wanted to shoot the man right there.

He didn’t.

Instead, he gave an order that would become legend in the mouths of the men who were there:

“Arrest him and put him in the cages. Let him see what it feels like.”

That SS officer was Josef Kramer.

The world would call him the Beast of Belsen.

And the capture of Josef Kramer wasn’t just another arrest in the collapse of the Reich.

It was the moment a division of tough, battle-hardened soldiers realized this war hadn’t only been about territory.

It had been about the soul of humanity.

And now they were standing at the gate of something that made battlefields look clean.

To understand why the British reacted the way they did, you have to see what they saw.

Bergen-Belsen was not Auschwitz.

It didn’t have gas chambers.

It wasn’t built as an efficient industrial killing machine the way some camps were.

It was, in your transcript’s words, something else entirely:

A horror camp.

A place where the Nazis dumped tens of thousands of prisoners and then stopped feeding them.

Stopped giving them water.

Let disease—typhus—rage through barracks until the camp itself became a biological catastrophe.

When the British rolled in, they found about 60,000 prisoners.

And they found 13,000 unburied bodies lying out in the open.

Thirteen thousand.

That number doesn’t make sense until you picture it. The ground itself turned into storage. The dead weren’t in graves. They were in piles, in ditches, on pathways, slumped against walls.

And the living—people still breathing—were sleeping on top of the dead because there was nowhere else to lie down.

That’s what the British saw.

Not one or two bodies. Not a mass grave hidden behind trees.

A landscape made of death.

One British officer, Lieutenant Colonel Mvin Gonan, later wrote that it was like a scene out of Dante’s Inferno.

He described a woman eating a raw turnip while sitting on her sister’s corpse.

Not because she was cruel.

Because starvation erases normal human reactions. It strips you down to the need to keep your body alive for one more hour. People weren’t screaming. They weren’t rioting. They weren’t even begging in the way the British expected.

They just stared.

And that stare broke men who thought they were unbreakable.

British soldiers had fought across France and into Germany. They’d seen blown-apart villages, dead civilians, wrecked tanks, men burned into black shapes in steel.

But this…

This made them sit down on their tanks and weep openly.

Not quietly wiping tears. Not turning away to hide it.

Grown men crying because what they were looking at didn’t fit inside any definition of war they’d been prepared for.

And in the middle of that—standing as if he was the manager of a hotel that had some unfortunate sanitation issues—was Josef Kramer.

Calm.

Unbothered.

His uniform immaculate.

His posture straight.

His riding crop held like a symbol of authority he believed still mattered.

He spoke to the British as if he was doing them a favor.

He said he’d done his best.

He said Berlin had stopped sending food.

He said the camp’s condition wasn’t his fault.

And then he shrugged.

That shrug—the complete absence of humanity—was the spark.

Because it wasn’t just that the British had discovered horror.

It was that the man in charge of it was acting like it was paperwork.

Like it was an inconvenience.

That’s what lit the fire of rage.

Josef Kramer wasn’t an accidental villain.

He wasn’t a clerk who got stuck in a post and tried to survive.

Your transcript makes him something darker: a career monster.

He joined the SS early.

He learned his trade at camps like Dachau and Mauthausen.

He became commandant at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Survivors described him as brutal. They said he would beat prisoners to death for walking too slowly. That he personally selected children for death. That he loved his job.

By 1945, he was transferred to Bergen-Belsen.

No gas chambers here.

So he used starvation.

He let the camp rot into disease because disease was free.

He didn’t have to pull a trigger to kill someone. He could simply ensure nothing arrived—no food, no clean water, no sanitation—and the camp would do the killing for him.

That’s why he was called the Beast.

Not because he looked like a monster.

Because he looked normal.

Like someone you’d pass on the street.

The kind of face you might see behind a counter in a bakery or driving a delivery truck.

And behind it, survivors said, there was nothing.

Kramer’s fatal mistake—when the British arrived—was thinking the British would behave like gentlemen.

He believed in rank.

He believed in uniforms.

He believed officers treated other officers with a certain formal respect, even in defeat.

He thought his SS insignia would still command something.

He was about to learn that the men of the 11th Armored Division weren’t arriving as diplomats.

They were arriving as witnesses.

And witnesses, when confronted with something like Belsen, don’t stay polite for long.

The arrest happened fast, and it wasn’t gentle.

Brigadier Hughes ordered Kramer disarmed.

A British sergeant walked up to the Beast.

Kramer sneered like he couldn’t believe anyone was touching him.

“Do you know who I am?” Kramer demanded.

The sergeant didn’t answer.

He slammed the butt of his rifle into Kramer’s stomach.

Kramer doubled over.

And in that moment, the arrogance vanished. Not because his ideology vanished, but because pain reminds you you’re still just flesh.

The British stripped him of weapons.

They tore off his medals.

They tied his hands behind his back.

Kramer protested, still clinging to the illusion of authority.

“I am a commandant. You cannot treat me like this.”

A British officer replied with a sentence that cut through rank like a knife:

“You are a murderer, and you will be treated like one.”

They didn’t put him in a proper cell.

They didn’t lodge him in some officer’s quarters.

They dragged him to what your transcript calls the ice box—an underground storage space, like a root cellar, cold and damp and dark.

They shoved him inside and slammed the metal door.

For the first time in his life, the Beast was in a cage.

Not as a man with power.

As a prisoner.

And the symbolism wasn’t subtle.

The British weren’t just imprisoning him.

They were stripping him of the fantasy that he was above consequences.

Kramer wasn’t the only monster they found.

Running the women’s camp was Irma Grese—twenty-one years old, blonde hair, blue eyes, a face that made newspapers later call her “the beautiful beast.”

But the beauty was irrelevant.

The cruelty wasn’t.

She carried a whip made of cellophane and used it to slash women’s faces. She had dogs trained to attack prisoners on command.

When the British arrested her, she wasn’t begging.

She was defiant.

Hands on hips.

Glare sharp.

As if she believed her youth, her appearance, her posture could protect her.

It didn’t.

The British had seen the scars.

They’d seen the fear in prisoners’ eyes when her name was spoken.

They put her in a cell next to Kramer.

And in the days that followed, she screamed, cursed, sang Nazi songs at the top of her voice like she could keep herself strong with noise.

The British guards didn’t give her special treatment.

They gave her the same rations the prisoners got.

Watery soup.

Stale bread.

The “master race” finally tasting its own medicine.

But arresting the SS wasn’t enough.

Because Belsen wasn’t just a crime scene.

It was an active catastrophe.

Bodies rotting.

Disease spreading.

Lice everywhere.

The British quickly realized something terrible: even liberation wasn’t instantly “safe.”

You couldn’t just open the gates and let people walk away. The prisoners were sick. Typhus was raging. The camp itself was contaminated.

And the British commander made a decision that combined practicality with something darker:

The SS created this mess.

The SS would clean it up.

They ordered the SS guards—men and women—to report for duty.

Not as guards.

As laborers.

And the prisoners watched.

Some cheered, because seeing the people who had tormented them forced into work was the first crack of justice they had been allowed to witness.

Bayonets pointed.

Orders barked.

“Pick them up.”

“Pick up the bodies.”

The SS guards—used to ordering others to do the dirty work—were horrified.

Now they had to touch the rotting flesh of their victims.

They had to carry bodies to mass graves.

No gloves.

No masks.

Bare hands.

And the British weren’t doing it as theater.

They were doing it because the camp had to be cleaned or the disease would keep killing.

Still—there was something undeniably humiliating about it, something designed to make the SS face what they had created.

And then—like war’s final cruelty—biology entered the story.

The bodies were infected with typhus. A deadly disease carried by lice.

The British forced the SS to carry bodies without protection, and whether or not it was intended as punishment, it became one anyway.

The camp turned against its creators.

Part 2

When the last trapdoor closed at Hamelin Prison on December 13th, 1945, it didn’t feel like triumph to the men who had been there.

It didn’t feel like victory the way a battle victory feels—flags, cheering, music.

It felt like something colder.

Like a door being shut.

Like a disease being cauterized.

Josef Kramer was dead.

Irma Grese was dead.

The Beast and the Beautiful Beast—names that had carried weight in newspapers—were reduced to what they had always been underneath the uniforms and mythology:

Human bodies.

Ropes.

Gravity.

And silence.

Albert Pierrepoint, the executioner, did his job the way he always did it—efficiently, professionally, without rage. He measured the drop. Checked the rope. Put the hood on. Opened the trap.

Kramer didn’t get a speech.

He didn’t get an audience.

He didn’t get to die as a symbol.

He died as a criminal.

And that distinction mattered.

Because part of what made Nazis like Kramer dangerous wasn’t just what they did.

It was the way they tried to dress it up afterward—orders, duty, bureaucracy, “the system.”

They wanted to turn mass murder into procedure.

They wanted to turn cruelty into job description.

The British trial—and then the hanging—ripped that disguise off.

It said: no.

You do not get to hide behind rank.

You do not get to hide behind “following orders.”

You did this.

You are accountable.

And now you are removed.

But the real ending of Bergen-Belsen did not happen in the courtroom.

It happened back at the camp itself, long before Kramer ever stood under a noose.

It happened the day the British soldiers walked through the gate.

The day the smell hit them.

The day grown men sat on tanks and wept.

Because something broke inside them there that didn’t heal just because the war ended.

Those soldiers had been hardened by combat—France, the push into Germany, the normal brutal math of war.

But Belsen wasn’t “war.”

It was industrial suffering.

And witnessing it rearranged their understanding of what they had been fighting for.

A lot of those men later said the same thing in different words:

They thought they were fighting to defeat Germany.

Then they saw Belsen and realized they were fighting to defeat something deeper—an idea that human beings could be turned into waste.

That was why the capture of Kramer mattered so much.

Not because he was the only monster.

Not because killing him made everything right.

Because in that moment, British soldiers made a decision that cut through all the noise of war:

They would not treat him like an officer.

They would not treat him like a gentleman.

They would treat him like what he was.

A murderer.

They stripped him.

They caged him.

They forced him to face the camp he had run.

And then they brought him to court.

The world needed that.

Because without court, Belsen becomes rumor.

Without evidence, horror becomes denial.

Without a record, the dead are killed again—this time by forgetting.

So the British documented everything.

They filmed the barracks.

They photographed the bodies.

They recorded witness statements.

They forced the SS to bury the dead not just as punishment, but because the dead needed burial and the camp needed to stop killing.

And then they did something that felt almost symbolic in its brutality:

They destroyed the camp itself.

After the survivors were evacuated to hospitals, Belsen was still full of lice and disease. The barracks were contaminated. The ground was contaminated. The place had become a source of infection as much as a symbol of evil.

So the British brought flamethrowers.

Bulldozers.

Fire.

They burned the wooden huts.

They tore down the guard towers.

They destroyed fences.

Not because they wanted to erase history.

Because they wanted to erase contagion.

They wanted the earth to stop being poisonous.

The sound of the fire consuming the camp became part of the memory too—wood cracking, smoke rolling up into the sky like the camp was finally exhaling all the death it had held.

Afterward, a sign was put up.

It didn’t celebrate a victory.

It didn’t boast.

It simply stated facts in the plain way facts are sometimes the only moral language left.

This is the site of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, liberated April 15th, 1945.

Thousands of unburied dead were found here.

Thousands more died after.

May they rest in peace.

That sign was quiet.

But it was a warning.

Because the most terrifying thing about Belsen wasn’t that it existed.

It was that it was run by people who looked ordinary.

A man who could walk up to a tank in polished boots, salute, and demand a truce—while behind him bodies lay stacked like firewood.

A young woman who could smile, fix her hair, whip prisoners, and believe beauty would protect her.

That’s what haunts people.

Not monsters with horns.

Monsters with paperwork and uniforms and normal faces.

That’s why the British soldiers’ rage made sense to those who smelled the smell.

Some people later said the British were too harsh in the first hours—rifle butts, humiliation, forcing guards to handle bodies bare-handed.

And in a clean moral universe, yes—violence against prisoners is wrong.

But those who were there said something harsher back:

You didn’t see what we saw.

You didn’t breathe what we breathed.

You didn’t watch living people sleeping on dead people because there was nowhere else to lie down.

They weren’t defending cruelty as policy.

They were describing human reaction to unimaginable evidence.

The kind of reaction that happens when the distance between “enemy” and “criminal” collapses instantly, because you’re looking at something beyond war.

Belsen was that.

And in that space, the British didn’t want polite justice.

They wanted immediate consequence.

They wanted the SS to feel—if only for a moment—what it was like to be powerless in a place of suffering.

Then, after the first rage passed, they did what matters most in history:

They turned rage into record.

They built a case.

They put the monsters on trial.

They executed them legally.

And they burned the camp so it could not keep killing.

That is how Belsen ended—not cleanly, not neatly, but with a combination of raw human fury and formal accountability.

And that’s why the story endures.

Not because it’s satisfying.

Because it’s necessary.

Because it reminds us that evil doesn’t always arrive as something obvious.

Sometimes it arrives polished and well-fed, holding a riding crop, insisting it did its best.

And the only thing that stops it is people willing to say:

No.

You don’t get to walk away.

Not as an officer.

Not as a bureaucrat.

Not as a man “following orders.”

You will be treated as what you are.

And then, once the anger is done and the record is written, you will be removed.

For the British soldiers of the 11th Armored Division, the liberation of Bergen-Belsen was the moment the war changed meaning.

It stopped being only about winning territory.

It became about proving that humanity still had rules.

That there were lines even war could not erase.

That people like Josef Kramer—no matter how clean their uniforms—would not be allowed to hide behind them forever.

The Beast of Belsen thought he was a god inside his camp.

In the end, he was just a man in a hood, dropping through a trapdoor.

And the world was better without him.

THE END

News

How To Interrogate a Narcissist

The Room Where the Story Changed The knife hit the table with a sharp, metallic clatter—an ordinary sound made suddenly…

(CH1) “The Americans Said, ‘Root Beer Float’” — Female German POWs Thought It Was Champagne

Part 1 April 12th, 1945 — Camp Shanks, New York The transport truck rumbled through the gates like it was…

(Ch1) Why Patton Carried Two Ivory-Handled Revolvers

Part 1 May 14, 1916. Rubio, Chihuahua, Mexico. Second Lieutenant George S. Patton crouched behind the corner of an adobe…

(CH1) You’re Mine Now,” The American Soldier Said To a Starving German POW Woman

Part 1 Northern Italy, April 1945. Corporal James Mitchell found her in the rubble of a communications bunker outside Bologna,…

(Ch1) Everyone Traded For New Tractors in 1980… He Kept His Farmall And Bought Their Land 15 Years Later

Part 1 The year 1980 was a fever dream for American farmers. That’s not exaggeration. That’s what it felt like—like…

(CH1) John Deere Salesman Called Him a Fool for Keeping That Farmall… 10 Years Later, He Bought His Farm

Part 1 The confrontation happened at the parts counter on a Tuesday morning in March 1981, in Tama County, Iowa—the…

End of content

No more pages to load