The fog rolled in thick off the Bristol Channel that morning, the kind that swallowed sound and smeared the outlines of ships into ghosts.

November 1942. A British dockyard, somewhere along a battered coast that had already endured two years of German bombs.

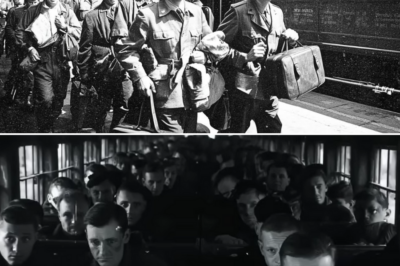

The transport eased up to the quay with a grinding moan, ropes thrown, bollards wrapped, gangways swung into place. On deck, pressed up against the rail, stood men in olive drab who’d crossed an ocean to fight in a war that, if they were honest, had not really been theirs to begin with.

Among them, wearing a too-stiff wool overcoat and a battered service cap, was Sergeant James Holley of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion.

He was twenty-two, a carpenter’s son from Birmingham, Alabama. He’d known heat and red clay dust and sawdust, the smell of pine boards and sweat and the crack of a ball hitting wood. He had also known the narrow world of “colored” stamped on every aspect of his life: colored schools, colored neighborhoods, colored churches. Segregated train cars. “Whites Only” water fountains. Guard shacks and bus drivers and sheriffs who made sure he never forgot who he was.

“Don’t forget who you are over there,” his mother had said, standing small and straight by the station platform, one hand on her hip, the other pressed flat against his chest as if to hold his heart in place.

As if he ever could.

The Army had done its best to remind him: segregated units, segregated barracks, segregated mess halls. Even here, as they squeezed toward the gangway, the white units were mustered separately, already tramping down the ramps to waiting buses, while the black battalion waited for orders.

But as James stepped ashore onto British soil with the rest of the 320th—two hundred black soldiers in unfamiliar uniforms—something in the air shifted.

The dock workers stared, sure. Hard not to. Many of them had never seen this many black men in one place in their entire lives. They took in the brown faces and the American uniforms and the balloons painted on the trucks and muttered to each other.

“Blimey,” one said, loud enough for James to hear. “They didn’t tell us they were sending coloured lads.”

Every muscle in James went tight. Back home, that tone led to the next thing: the narrowed eyes, the spit, the casual how-dare-you-breathe-our-air threats. The barman refusing to serve him, the policeman crossing the street.

But the dock worker just… shrugged.

“Lads is lads,” he said, and turned back to a crate, muscles bunching under his overalls as he swung it onto a pallet.

James let out a breath he hadn’t realized he was holding. Beside him, Private Marcus Wright from rural Georgia shot him a quick look. The same question was in both their eyes.

What the hell?

They didn’t say it. They’d both learned young that it was dangerous to trust a moment just because it felt different.

The first week in Britain passed in a blur of work and cold.

They were billeted on the edge of Bristol, a battered port city still wearing its scars from the Blitz. Bombed-out shells gaped along streets of intact row houses. Whole blocks were nothing but rubble and weeds. At night the searchlights swung through the sky, pale fingers probing for enemy bombers that sometimes still came, though less often than before.

The 320th’s job was simple and exhausting: balloon positions, anti-aircraft defenses. They manned winches and cables, coaxed great sagging silver sausages of hydrogen into the sky, anchoring them above factories, docks, and rail yards. The balloons were ugly-beautiful, lumbering up into the clouds, their tethers humming when the wind caught them right. Their very presence said to any German bomber pilot: come low and you’ll rip your belly out.

James had never imagined that his war would be about rope tension and height calculations. He’d imagined guns and mud and the usual fantasies of young men who hadn’t yet found out what war really was.

The small things bewildered them far more than the military routines.

The first time they walked into a British pub in Clifton, the owner, a man with a worn bar rag and the look of someone who’d seen his city burn and kept serving anyway, simply nodded and poured.

“What’ll it be, mate?” he asked.

James stood there dumb, thinking there must be some mistake.

Back home, you didn’t walk into a bar where white men drank.

“Beer,” Marcus said finally. “Just—beer.”

The pints came: cloudy, warm, bitter in a way American beer never was. After the first careful sip, James decided he liked it. After the second, he decided he liked the feeling even more: sitting at a table, in public, with white men at the next table over, and no one staring daggers or telling him to move.

The first time it really broke his brain was outside a picture house on White Ladies Road.

He and Marcus were walking back from setting a balloon near the zoo, wool coats buttoned up to their throats, breath ghosting white in the November air. People moved around them, heads down against the cold, RAF uniforms mixing with factory overalls and the occasional suit.

A girl, maybe nineteen, stepped out of the cinema queue. Dark hair curled just so, scarf looped around her neck, lipstick carefully applied despite the blackout and rationing.

She caught James’s eye and smiled.

Not a small, tight, nervous smile. A real one. Quick, wide, there-and-gone.

She turned back to her friend, laughing at something, and didn’t glance back.

James walked three paces past before his legs remembered how.

“Did you see that?” Marcus hissed.

He nodded once, throat dry.

Back home, that kind of smile could get you killed. Not her, him. There would be whispers, and then there would be men waiting in the dark.

Here, it had been nothing. A girl at a cinema on a cold night, acknowledging a man in uniform.

“Maybe they don’t know,” Marcus said later that night, as they lay in their cots in the Nissen hut, the curved corrugated steel roof pinging softly with rain.

“Know what?” James asked, though he already knew.

“How it’s supposed to work.”

He found out exactly how it was supposed to work when the military police showed up.

The American MPs arrived in Bristol like they arrived everywhere the Army went: white armbands, white helmets, batons at their belts. Home had come with them: the rules, the lines, the knowledge of who belonged where and who didn’t.

They tried to carve out a little Alabama and Mississippi and Georgia right there in the middle of Britain.

They stood outside pubs and told owners, in firm, unaccented American English, that they shouldn’t serve “colored” soldiers in the same room as whites. They tried to designate certain pubs as “white only” by threat, not law. They glared at British girls who danced with black GIs in the town halls and YMCA socials that dotted the calendar.

And Britain, shellshocked and weary as she was, quietly said: no.

The mayor of Bristol issued a statement: all Allied servicemen would be welcomed in public establishments, regardless of race. The local paper printed an editorial, careful but clear, reminding readers that Jim Crow was an American practice, not a British one.

Pub owners put up small hand-printed signs: “All Allied Soldiers Welcome.” And they meant it.

The stories spread through the barracks like warm air.

In Liverpool, a black GI thrown out of a pub by an American MP saw the MP, not him, escorted to the door by two burly British dockworkers. In Bath, American officers who tried to shut down a dance because black soldiers were present found themselves facing not only angry black GIs, but white British soldiers and civilians who told them, in no uncertain terms, to leave.

In a village outside London, a local women’s committee sent a polite but firm note to the American base commander: they would not agree to separate social events. They would dance with whomever they pleased.

It was a strange sort of battle. No artillery. No flak. Just stares and words and the simple revolutionary act of serving a pint to a man the Americans said shouldn’t have one.

One night, James saw both worlds collide.

Colston Hall had survived the worst of the Blitz. The big municipal hall had been blacked out, its stained glass covered, its chandeliers gone dark, but its ballroom still echoed with music on some Saturday nights. The city needed somewhere to remember joy.

The Red Cross posted notices: “Dance for American Colored Troops.” A special event just for them, because it was clear the Army wasn’t going to make room for them at the larger gatherings.

The hall was packed. Black GIs in their best uniforms. British girls in dresses let out and patched, their hair done up with a pride the bombs couldn’t touch. The band played American swing, brass slick and bright, the rhythm section holding it all up.

James stood against the wall at first, watching, the bass drum thumping in his chest.

“Are you going to stand there all night, then?” a voice asked.

He turned. A blonde girl in a green dress stood with her hands on her hips, head cocked. She looked him in the eye.

“Or are you going to dance with me?”

He could barely process the question.

“Yes, ma’am,” he heard himself say, because his mother had raised him with manners, even in the face of miracles.

Her smile flashed. She took his hand, tugged him toward the dance floor. For three minutes, they moved together, feet finding the beat, bodies cautious then looser. He smelled lavender soap and cigarette smoke. She giggled when he stumbled, then corrected his step with a gentle hand on his shoulder.

No one pulled her away. No one shouted. No one reached for a badge or a baton.

When the song ended, she thanked him and disappeared into the crowd.

His hands shook for ten minutes afterward.

That night, on the walk back, he told Marcus about it.

“Man,” Marcus said, “imagine us doing that in Birmingham.” He let the thought hang there, the impossible weight of it filling the space between them.

Of course, the Army had its own ideas about “impossible.”

The first time James saw an American MP club a black soldier outside a pub in Broadmead, he felt something in his chest go cold.

The soldier was a corporal from Ohio, drunk but not disorderly. He had wandered into a pub where white GIs sat at the bar. The British barkeep had served him without blinking.

The MPs arrived ten minutes later.

“You know you ain’t supposed to be in here,” one barked, and when the corporal didn’t move fast enough, the baton came down. Hard. Once across the back. Once across the shoulders. The corporal went to his knees. The barkeep shouted something furious in Bristol dialect. One of the British regulars stood up, fists balled.

“Take him outside,” the MP snarled. “We’ll teach him his place.”

That last word was the only one James really heard. Place. He’d grown up with that word tattooed on his existence.

He watched it play out again in Bath. And in a little village near Weston-super-Mare. By the third time, he had stopped being shocked.

British civilians were shocked, though. Outraged even. Not because they were free of their own prejudices—they weren’t—but because the raw, codified brutality of American racial policy was visible in a way that their own more subtle class hierarchies weren’t.

Local newspapers ran editorials condemning the treatment. The BBC aired carefully worded radio programs talking about the contributions of colonial troops and black Americans to the war effort. MPs in Parliament raised questions that never made it into the official record, but made their way into the rumour mills.

Not all of it helped the men on the street. But it helped them know they weren’t crazy. That what they were seeing was wrong, and that at least a few people in power were willing to say so.

And then there was the story about the queen.

James first heard it sitting on the edge of his cot in a cold Nissen hut outside Bath, the corrugated steel roof dripping condensation like the hut was sweating.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Morrison had come down from HQ to talk to the men of the 92nd Infantry Division and the 320th Balloon Battalion—some rare moment when someone higher up remembered that black units existed and occasionally needed words.

Morrison was one of the few black officers who’d made it that high. He wore his uniform like armor and chose his words like tools.

“I was at a planning meeting yesterday,” he said, voice low but carrying. “British liaison officers, American staff. Deployments, logistics, all that. One of the British colonels—proper old school type, educated, well-spoken—asked our commanding officer how to ‘accommodate’ the Negro units.”

James shifted, already bracing for what came next.

“Our CO starts talking about separate facilities. Separate recreation. The same nonsense we get back home. The British colonel just looks at him. Doesn’t shout, doesn’t bluster. Just says very quietly, ‘That will not be possible on British soil. His Majesty’s government does not recognize such distinctions.’”

A few men chuckled skeptically. It sounded good. Too good.

Morrison’s mouth twitched. “Our man starts arguing. The Brit cuts him off. Tells him the matter’s been discussed at the highest levels. Says when Her Majesty the Queen”—he paused, knowing the weight those words carried—“heard that American Negro troops were coming, she asked to be assured they would be treated with the same respect as any Allied servicemen. Not less. Not separately. The same.”

Silence settled over the hut. Not reverent. Just… stunned.

“Now,” Morrison said, raising a hand, “I don’t know if those were her exact words. Stories grow in the telling. But I know for a fact that something was said, high enough that our brass had to sit up and pretend to listen. And I know for a fact that British authorities are not keen on importing Mississippi into Manchester.”

A ripple of dark laughter moved through the hut.

Morrison’s eyes found James’s in the crowd.

“Don’t misunderstand me, boys. This doesn’t make Britain paradise. Doesn’t fix the Army. When this war is done, you’re going back to the same country that sent you here to fight but won’t let you vote. But I want you to remember this much: somewhere in the machinery of power, somebody looked at what’s happening and said, ‘This is wrong.’ Not impolite. Not inconvenient. Wrong.”

That night, James lay awake, listening to the damp drip from the roof. He pictured a small woman in pearls and a hat, listening to someone explain American segregation and feeling something like disgust.

He didn’t know her. She sure as hell didn’t know him. But the idea that someone like that might have spoken, even in a limited, polite, aristocratic way, on behalf of men like him?

It was a strange kind of comfort. A borrowed spine.

He saw her once, or thought he did.

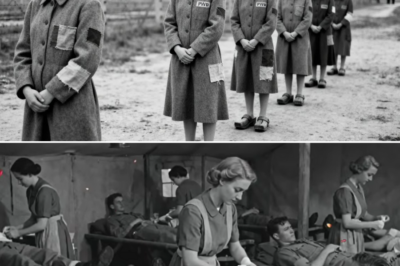

March 1943. The Queen Mother toured a hospital in Bristol that housed wounded from North Africa. The 320th had been assigned as extra security. James stood at attention outside the entrance, balloon patch on his sleeve, rifle slung properly, uniform pressed as best as a wartime laundry allowed.

The official car pulled up. A cluster of officers gathered. And then she stepped out: shorter than he expected, wrapped in a dark coat, hat perched just so. Her face looked older than the picture on the money, lined from worry and the weight of Blitz years. She moved through the line of men with a practiced grace, stopping here and there to speak.

For a moment, her gaze swept toward where James and two other black soldiers stood.

Her expression did not change.

She did not flinch, did not frown, did not beam some exaggerated warmth. She just looked at them as she’d looked at the white orderlies and the white guards and the wounded coming down the corridor: with the polite, distant attention of someone for whom all of this suffering had become both personal and abstract.

Then she moved on.

It was the smallest of things. But it stuck.

She had, in that second, not marked him as something other. That alone separated this moment from every interaction with authority he’d ever had back home.

War compresses time.

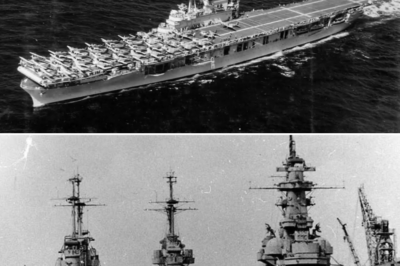

By 1944, the Americans were in Italy, then Normandy. Black units went where they were sent: the 92nd Infantry in Italy, engineer units everywhere, the 320th’s barrage balloons floating above Omaha Beach on D-Day, their cables shredding the wings of German planes that tried to attack low.

James stayed in Britain longer than many, watching the tide of war turn. Watching fewer bombers come from the east and more go the other way, wearing American stars and bars. Watching British civilians endure rationing and grief with a stubbornness he came to recognize as kin to his own people’s.

He danced in more halls. Drank in more pubs. He took blows from MPs and saw white Brits thrown out alongside him when they sided with him against some particularly arrogant officer.

He formed a picture in his mind: America was a place where the government could be strong and also cruel. Britain was a place where the government was weaker but sometimes, in small ways, braver.

Neither was heaven. Both were better than a boot on your neck.

When the war ended, the orders came: go home.

He stepped back onto a ship, then a train, then a bus, then into Birmingham’s heavy summer air. The signs were still there: COLORED at the back entrance of cafes, WHITES ONLY over the front. Police eyes still followed him too closely. The Klan still held meetings in the bottoms.

The temporary freedom he’d known in Bristol dissolved like fog over water.

But it didn’t vanish.

It lived in his memory and in the stories he told.

He became a carpenter, like his father. Built houses for white folks he wasn’t allowed to live near. Married. Had children.

At night, when the radio talked about civil rights and Brown v. Board and Little Rock, he’d tell his kids, “I seen a place where they served me a beer in a white bar and nobody said a damn thing. I danced with white women and the roof didn’t fall in. Don’t let anybody tell you it can’t be different. I know better. I saw it.”

He told them about the Queen Mother’s glance. About the British colonel’s quiet “not on our soil.” About the dock worker’s shrug.

He told them about the ones who beat him and the ones who stood next to him anyway.

The story about the queen’s words grew in the telling, of course. Maybe she had said exactly that. Maybe she’d asked something vaguer like “I trust they will be treated properly?” Maybe it had never reached her ears at all and had been created by British officers who needed to invoke her name to give their own resistance weight.

The point was not whether the quote was perfect.

The point was what it meant to believe it came from her.

That somewhere high in a palace across the sea, someone with power and privilege had at least tried to insist that men like him be treated as allies, not livestock.

In the end, that knowledge—that things had once been different, that even temporary justice had been possible—was its own kind of ammunition.

When he stood in a line to vote, years later, after the Voting Rights Act, he thought of standing in line for beer in Bristol.

When he rode a bus and didn’t have to move for anyone, he thought of riding on English trains with white soldiers and nobody flinching.

When his daughter brought home a school textbook with pictures of black GIs in Britain dancing with white girls in bomb shelters, he pointed at it and said, “That wasn’t just a picture. That was me. Not in this photo, but in those halls. Don’t let anybody tell you that freedom was handed to us. We tried it on overseas, then came back and made them give it to us here.”

It would take marches and dogs and fire hoses and blood to make that true. But the memory of those months in England mattered. They were a crack in the wall.

For a few months, in a small island nation under siege, men like James were treated almost like what they were always told they weren’t: men.

Not saints, not martyrs, not symbols.

Just men.

And once you’ve known that feeling, it’s harder to settle for less.

That realization—shared quietly among thousands of black veterans who came back from Europe and the Pacific with stories in their pockets—is one of the war’s quieter victories.

Not marked in medals. Not carved into stone. But carried in hearts like James’s, passed down like a family secret and a promise:

The world doesn’t have to be this way.

We’ve seen it otherwise.

News

(CH1) Captured German Officers See a US Aircraft Carrier for the First Time

The first time they heard about the American carriers, most of the officers in the Kriegsmarine laughed. It was early…

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) He Taught His Grandson to Hate Americans — Then an American Saved the Boy’s Life

January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed. In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul…

End of content

No more pages to load