By the time the hatch slammed shut on the Liberty ship and the Atlantic swells began to lift the hull, most of the men in the hold had finally stopped joking.

They had called America soft.

They’d laughed in foxholes and bunkers that GI’s lived on chocolate and coffee, that their uniforms came with candy bars sewn into the pockets, that their factories mass-produced chewing gum instead of discipline. Around smoky fires, German soldiers told each other that while they survived on black bread and cabbage soup, Americans needed steak and Coca-Cola just to pick up a rifle.

“Let’s see how these spoiled Americans feed us,” some sneered as they were herded aboard, pretending not to notice the hollowness in their own cheeks.

But beneath the bravado, another feeling lurked. Unease.

They had been told everything about America: that it was poor, chaotic, racially rotten, still paralyzed by the Great Depression; that its politics were corrupt, its culture degenerate, its people weak and divided. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda machine poured out this image for years, and for men whose only other view of the world came through army newspapers and Party lectures, there was little reason to doubt it.

So when capture came—at Kasserine in North Africa, in the hedgerows of Normandy, outside ruined French villages—many of these soldiers believed they knew what awaited them. Barbed wire cages, starvation, beatings. The same treatment they had watched meted out to captured Russians and Poles. The thought of being sent across the ocean to the United States only magnified their dread. If their own regime could be so brutal toward prisoners, what would the “decadent” enemy do?

On the endless gray water of the Atlantic, these stories followed them like ghosts.

The holds stank of sweat, vomit, and fuel oil. The threat of their own navy’s U-boats prowling beneath the waves added a sharp edge of irony. They could be sunk by German torpedoes before they even reached America. Each time the engines changed pitch, conversations stopped. Men strained to hear whether it meant danger or merely a change of course.

And then, after days of rocking darkness and the metallic taste of anxiety, the ship slowed.

The first sight of America

The prisoners saw it in fragments at first.

Through a porthole, a skyline bristling with buildings that seemed to stab the clouds. Cranes stalking across harbors where freighters and tankers queued two, three deep. Trains rattling along elevated tracks, full of cargo rather than evacuating refugees. Smoke drifting not from burning cities but from factory stacks working at full power.

For men who had watched Hamburg, Cologne, and Berlin turned to ash, the sight of a fully lit, fully functioning city was almost unreal. No bomb scars. No hollowed-out blocks. No blackout curtains.

One former prisoner later wrote, “We had been told America was starving. Yet in the harbor, I saw ships loaded with bananas, oranges, and meat. It was the first time I realized something we had been told was wrong.”

They were marched down gangways under guard. The guards were armed—but they were not screaming. Commands were short and clear. The column formed without blows or butts to the ribs. The prisoners were loaded onto trains that seemed to stretch forever into the distance.

Through barred windows, the country unspooled: neat rows of corn and wheat, red barns, towns with movie theaters and drugstores, highways full of cars even in wartime. It did not look like a land of unemployment and chaos. It looked organized. Busy. Almost obscenely intact.

On those rattling carriages, the laughter died away for good. In its place was a quiet reckoning.

The mess hall that broke propaganda

For all that, most prisoners clung to one last illusion: that their captors would reveal their true nature through food.

Germany, after all, had turned food into a weapon. Rations at home shrank each year. Civilians stood for hours in line to buy dark bread cut with fillers, ersatz coffee made from roasted barley, soup so thin it barely colored the water. At the front, soldiers went hungry more often than not. They watched the regime deliberately starve conquered populations and treat prisoners as expendable labor.

So the Germans expected their own captivity to mirror this. Thin soup. Hard crusts. A deliberate grinding down of strength and dignity.

The barbed wire of the first camps in America looked familiar enough. Guard towers. Floodlights. Rows of barracks. The smell of dust, sweat, and disinfectant. They filed into the mess halls braced for the worst.

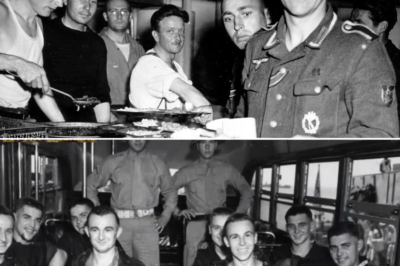

Then the kitchen doors swung open.

Steam billowed from vats of stew thick with beans and meat. Loaves of bread, soft and white, lay stacked beside tubs of butter and jam. At breakfast there was oatmeal, eggs when supply allowed, sometimes even bacon. Coffee—not the burned substitute they knew, but real coffee—filled metal urns. Prisoners watched American cooks ladle food onto their trays in portions larger than anything they had seen at the front.

“The first meal, no one spoke,” a former P.O.W. recalled. “We sat there staring at the plates like they would be taken away. Then we ate, and it was like waking up from a bad dream.”

It wasn’t a one-time gesture. The abundance continued. Three meals a day, every day, regulated by the Geneva Convention, which required that prisoners receive the same basic ration as American soldiers. By 1944, that meant roughly 2,800 calories a day for P.O.W.s—more than many Germans back home saw in a week.

A staff sergeant in charge of one camp kitchen in Texas later noted in his logs that the prisoners “often looked guilty when receiving meat and sugar, knowing their families in Germany had none.”

The irony bit deep. Men who had considered themselves hardened warriors, superior in discipline and endurance, found themselves putting on weight behind barbed wire while their families wrote from bombed-out cities about hunger and cold.

Work, fields, and quiet kindness

The United States did not build all this infrastructure out of pure charity.

Under the laws of war, prisoners could be required to work so long as it didn’t directly support combat operations. With millions of American men abroad, farms and factories at home were short-handed. German prisoners became the solution.

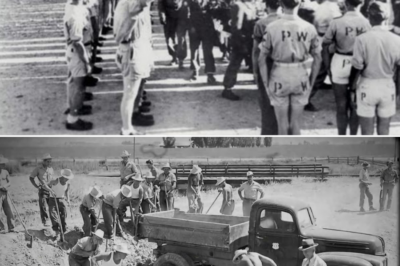

They were trucked to cotton rows in Texas, to sugar-beet fields in Minnesota, to orchards in California and canneries in New Jersey. They cut timber in Southern forests and moved freight in Midwestern depots. They wore stenciled “PW” on their dungarees and worked under guard, but the work itself was often no harsher than what they had done in peacetime at home.

There, something even stranger happened.

Farmers who had first looked at them with tight jaws and wary eyes realized these young Germans with sunburned necks and calloused hands were not so different from their own sons overseas. A farmer in Iowa brought pies out to the fields one hot afternoon. A woman in Georgia slipped extra biscuits into a prisoner’s hand. In the South, some German P.O.W.s were stunned to find that, as enemy soldiers, they could eat in restaurants or enter town shops more freely than Black Americans could under Jim Crow laws—a contradiction that baffled and unsettled them.

“We were enemies,” one prisoner remembered. “But she smiled at us. That small kindness was more powerful than any propaganda.”

In many camps, prisoners were paid token wages in scrip they could use at the camp canteen. They bought smoking pipes, paper, soap, even small radios. They organized orchestras and theater groups. They played soccer against American teams. Some ran classes in mathematics or languages.

It was captivity, but it was structured, predictable, almost civilized.

The guards, by and large, followed rules. Beatings or abuses did happen, but they were rare and often punished. There were no mass shootings, no deliberate starvation policies. Discipline came from paperwork and regulations rather than clubs.

To men who had watched their own army crush prisoners, this was another shock. The enemy, who could afford to treat them well, chose to. It said something about the strength—and the confidence—of that enemy.

The country outside the wire

The strangeness did not end at the camp fence.

On transport days, as trucks rolled through American towns, P.O.W.s caught glimpses of a society that had been at war for years and yet bore hardly any scars. Movie theaters advertised Hollywood pictures. Supermarkets displayed piles of fruit and canned goods behind gleaming glass. Kids rode bicycles down clean streets. Neon signs buzzed over diners where coffee and pie were served through the night.

For soldiers whose mental picture of the United States had been cobbled together from Nazi caricatures, these sights were a quiet but devastating rebuke.

One prisoner wrote years later, “In Germany, we heard that America was collapsing. In America, I saw a nation overflowing. I realized then who had been lying to me.”

That realization did not come overnight. Pride dies slowly. In the barracks, there were arguments. Hardened Nazis insisted that all this abundance was a façade, that the Americans were soft, that their kindness was calculated. Others began to speak more openly.

“If we had this food, these factories, this oil,” one man told his bunkmate, “perhaps we would also be generous. But we do not. And that is the point.”

The oil was no exaggeration. In 1944 alone, the United States pumped around 1.8 billion barrels of crude. Germany, strangled by bombardments and blockades, managed barely a fraction of that, and Japan even less. American industry dwarfing Axis production wasn’t just a statistic to these men; it was visible in every mess hall, in every new truck, in every ration crate stamped “U.S.A.”

Fairness and paradox

For many prisoners, the most powerful impression was not simply the food or the work, but the fairness.

They saw guards reprimanded for mishandling prisoners. They watched officers insist that Geneva Convention rules be followed. In many camps, there were complaint boxes, and grievances were actually investigated. When P.O.W.s were killed in accidents or disease, they were buried with markers and records kept. The machinery of the US Army, however vast and impersonal it sometimes felt, acknowledged their humanity in ways their own army had not always done.

And yet, the same prisoners sometimes saw Black American soldiers segregated into separate units, sent to do the hardest labor, or denied service at Southern diners that had no problem feeding German captives. They watched Italian P.O.W.s freely chat with locals while African American civilians were forced to enter buildings through the back door.

It was a paradox as sharp as anything they had seen in war: a nation capable of such generosity toward enemy soldiers could be blind to injustice at home.

That contradiction did not cancel out what they experienced. If anything, it made them think harder. In their letters and later memoirs, many former P.O.W.s wrote with both admiration for America’s abundance and discomfort at its racial inequalities. It was, for them, the first look at a democracy in all its messy imperfection.

Nazism dies one meal at a time

The war ended in May 1945 for Europe, but for the P.O.W.s, it wound down slowly. For months and then years, many remained in camps, working, eating, thinking.

Some took part in formal re-education programs. The US and British authorities provided books and lectures on democracy, the rule of law, and the crimes of the Nazi regime. Posters and films documented the concentration camps’ horrors. For some men, these intellectual efforts mattered. But for many, the most convincing argument had already been made in silence.

A full plate in the messaul.

The orderly rows of houses in towns untouched by bombs.

The cook’s casual “Morning, boys” as he handed an enemy soldier a steaming mug of coffee.

“I did not abandon Nazism because of pamphlets,” one former P.O.W. admitted. “It was the food. It was the fairness. It was seeing a system so confident in its strength that it could afford to treat us well. That was stronger than any lecture.”

The numbers behind it were staggering. Between 1942 and 1945, roughly 425,000 Germans were held in nearly 700 camps across 46 US states. Almost all went home eventually. But they did not return unchanged.

They stepped off trains into a Germany of ruins and hunger, families living in cellars, children playing among the rubble of cities the Allies had firebombed. They saw ration cards where they had once seen surplus. They smelled coal smoke and damp, not coffee and bananas. Their first instinct was often guilt. They had eaten better as prisoners than their own people had as citizens.

Yet many also brought back a different kind of cargo: stories.

They told their families and neighbors about the America they had actually seen, not the caricature their propaganda had drawn. They talked about supermarkets overflowing with goods, about factories humming day and night, about farms that seemed to stretch forever. They described guards who followed rules, farmers’ wives who brought pies, pastors who came to offer them Bibles, and the strange notion that even in war, you could treat your enemy decently.

Some never stopped thinking about it. A few returned to settle in America after the war, marrying women they had met while working in the fields, or coming back years later under immigration programs. Others stayed in Germany but carried a lingering respect for the system they had seen.

The real face of strength

The story of German prisoners in America is not a simple tale of kindness. It does not erase bombed cities or concentration camps or the brutality that defined much of World War II. It lives alongside all that—uncomfortable, unexpected, and true.

Inside those camps, behind barbed wire and watchtowers, thousands of men experienced a reality that didn’t match anything they had been told. A democracy they had been taught to despise proved itself resilient. A people mocked as soft turned out to be industrially unstoppable. A military they had expected to mirror the cruelty of their own instead followed rules, not always perfectly, but often enough to astonish those on the receiving end.

In the end, what shocked them most was not American firepower. It was American abundance—and what that abundance allowed.

The United States did not need to starve its enemies to feel safe. It did not need to beat prisoners into submission to prove its dominance. It could, and often did, choose to feed them, house them, and treat them as human beings, even while its own sons were still dying overseas.

That quiet confidence—the ability to win a world war and still put bread, meat, and coffee on a prisoner’s tray—spoke louder than any slogan. For thousands of German soldiers, it cracked open the lies they had lived by.

They had mocked America as soft. In the end, what they found was something harder to understand and harder to defeat: a strength built not just on weapons, but on the power to be merciful.

News

(CH1) The German POWs Mocked America at First—Then They Saw Its Factories

When the train slid to a stop in Norfolk in January 1944, the men inside braced themselves for the worst….

(CH1) “It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

By the time the trucks pulled up to the gate at Camp Swift on May 12th, 1945, Texas heat had…

(CH1) The German POWs Laughed at American Food—Then They Ate in US Camps

They had laughed at America long before they ever saw it. Around smoky campfires in Russia and under low tarpaulins…

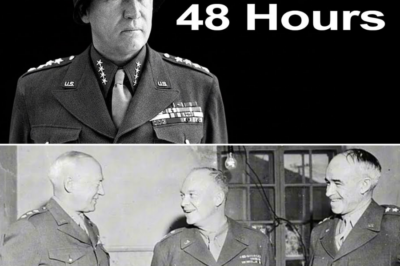

(CH1) Why Patton Was the Only General Ready for the Battle of the Bulge

On the night of December 19th, 1944, in a converted French army barracks at Verdun, the air in the conference…

(CH1) “He Gave Me His Blanket” — How a Frozen American Soldier Saved a Little Girl in the Ardennes

On the night of December 22nd, 1944, the Ardennes forest seemed to have turned entirely to ice. Snow swallowed the…

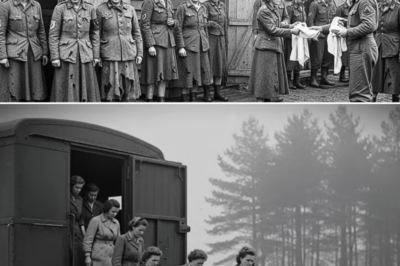

(CH1) German Women POWs Hadn’t Bathed in 6 Months — Americans Gave Them Fresh Uniforms and Hot Showers

On the morning of March 12th, 1945, the train rolled to a halt in a foggy corner of rural Georgia….

End of content

No more pages to load