On the morning of January 11th, 1944, the sky over central Germany looked like it was being erased.

From his P-51’s cockpit at twenty thousand feet, Major James Howard watched the stream of B-17s below him push into a rising wall of cloud. Each bomber was a silver cross against the gray, four engines drawing white contrails across the frozen air. Six hundred Fortresses and Liberators, stretching from one horizon to the other, all headed for the factories around Oschersleben and Halberstadt.

Howard scanned above and behind them. Nothing yet. The radio crackled with fragmentary calls from other squadrons, vectors from ground control, clipped status reports from bomber formations whose voices he’d begun recognizing by tone alone.

“Third Division on course…”

“Flak heavy over Magdeburg…”

“No fighters sighted yet…”

They all knew what was coming.

He checked his fuel, his ammunition counters, his drop tanks. The Merlin ahead of him felt smooth and eager, humming through the stick. Somewhere off his right wing, the rest of his flight held formation, white exhaust trailing in ordered lines.

“Eyes open, boys,” he said into the mic. “Jerry knows we’re headed for his heart this time.”

He’d flown in China with the Flying Tigers. He’d seen Japanese pilots commit suicide dives rather than be taken. He’d watched American pilots bleed out in bamboo cages. He thought he knew what desperate courage looked like.

He hadn’t yet seen it through the eyes of his enemies.

Down below, in a dim briefing room near Halberstadt, Oberleutnant Karl Rehm sat on a wooden bench with half a dozen other fighter pilots while the operations officer pointed at a map speared with colored pins.

“American bomber raid from the west,” the officer said. “Eighth Air Force. Primary target, Oschersleben. Secondary, Halberstadt. We estimate three hundred bombers.”

The men around Karl shifted, some whistled softly. Three hundred. Heavy stuff, but they’d seen it before.

“Escort?” someone asked.

The officer’s jaw tightened.

“P-47 Thunderbolts and P-38 Lightnings. Maybe Spitfires at the edges. Nothing new. They’ll have to turn back near the border. As always.”

The men nodded. It was an old pattern. The American fighters peeled away over the Netherlands, the bombers plowed on alone, and the Luftwaffe pounced.

Inside that briefing room, it was still 1943. The future hadn’t arrived yet.

Outside, on icy runways in England, it was already warming up.

Howard led his squadron out over the North Sea, Mustangs strung behind him like the tail of an arrow. The cockpit smelled faintly of oil and canvas and cold aluminum. Light frost crackled off the canopy when he pushed it back to wipe a clearer view.

Below, the gray water was flecked with the wakes of ships. Above, a scattering of high, thin cloud. The air was smooth, the Merlin’s song steady in his bones.

“Pioneer Group, this is Red Leader,” Howard called. “Check in.”

Voices replied, callsigns threaded through static. It was always like this at the beginning, routine and almost peaceful. The trouble came later, when the horizon filled with black puffs of flak and enemy fighters weathered like hawks.

He’d been told to escort a different bomber division that day. But missions rarely survived contact with reality.

They crossed the German coast under a low shelf of cloud that mirrored the flat land beneath. Wind turbines spun lazily near the shore—German industry still breathing. The bombers droned below, lines tightening as they approached their target area.

“Fighters six o’clock high!”

The first call came from a bomber group somewhere behind and to the left. Howard craned his neck, eyes sweeping the sky. For a moment he saw nothing.

Then he saw them.

High and dark against the haze, like flecks of ash, they dropped out of a patch of cloud. Thirty, maybe more. Two engines here and there—JU 88s or Me 110s—escorting flocks of single-engined 109s and Fw 190s.

“Here they come,” Howard muttered.

He keyed his mic.

“Green and Blue flights, stay with the Forts,” he ordered. “Red Flight, we’re pushing out. Let’s spoil Jerry’s party.”

They climbed, engines straining as they hauled their drop tanks, banking into the oncoming wave.

From Karl’s perspective, the sky looked different that day.

His unit had scrambled from their field near Oschersleben as soon as the sirens began. The thin winter light stabbed at his eyes as he climbed his Bf 109 through fourteen thousand, fifteen, eighteen. Breath rasped in his mask. The canopy frame rattled softly as slipstream clawed at the plexiglass.

“Enemy bombers sighted,” control called. “Heading one-three-zero. Height, five thousand meters. No escorts observed beyond the border.”

Karl felt that familiar tightening in his chest that wasn’t quite fear. This was what he’d trained for. This was why he’d flown hundreds of sorties. Somewhere down in that formation were the machines that had turned his uncle’s town into rubble.

“Two Staffel, climb and turn east,” his Staffelkapitän ordered. “We’ll attack head-on, break through, then climb and do it again.”

Karl could almost recite the tactic in his sleep. Approaches by clock positions. Cannon aim points. When to break off to avoid colliding with the lead bombers.

He never saw the P-51 that killed his best friend.

One second his wingman’s 109 was there beside him, silver nose and black crosses. The next, tracers stitched across it from above, the canopy burst, the engine erupted, and the aircraft folded gracelessly into a fireball.

“Dietrich!” Karl shouted. “Dietrich, roll!”

Silence.

In the shock of that moment, he almost missed the sleek shape that dove between their formation and the bombers, guns flashing. Not a P-47. Too slim. Not a Spitfire. Wrong wing. It was something else, something faster.

He jinked hard and felt a line of bullets tear through the air his fuselage had just vacated.

Back in the Mustang, Howard had no time to count his kills. It was like diving into a school of piranhas.

The German fighters were coming in from all angles, focused on the bombers, confident their old rules still applied. He broke their formations, flying directly into the path of attackers, forcing them to break off or risk collision.

He fired at a 109 that streaked past, saw pieces fly off its wing root. He rolled, spotted a Focke-Wulf lining up on a straggler below, dove behind it and held the trigger until the guns clicked empty. In minutes, his ammunition counters dropped to zero.

He had one Mustang and a sky full of enemies. He should have turned for home. Every training manual, every tactical brain cell said so.

But below him, the bombers were taking hits, dropping from the formation trailing flame. He thought of the crews inside—twenty-year-olds who couldn’t even see the fighters shooting them apart.

Howard shoved the nose down again.

“Why isn’t he leaving?” one of the bomber pilots asked later in debriefs. “We could see his guns stop firing. He was still there. Still flying at those Krauts like he had an entire squadron behind him.”

He made pass after pass with empty guns, using the Mustang’s speed and newfound climb to bluff attacks, forcing German pilots to jink, to break their runs, to bleed energy. Several later swore he’d rammed one of their number deliberately. The only thing Howard hit was the spotlight of history.

Down below, in what had moments ago been German airspace, it now felt like someone else’s. The Luftwaffe pilots who survived that day carried the story with them. An American fighter, unknown and unwelcome, that refused to leave.

The old calculus—wait for the Thunderbolts to turn back, then feast—was broken.

The break hadn’t come overnight. It had started weeks before the mission that would make Howard famous.

In December 1943, when the first Mustangs had shown up over Kiel and Bremen, the German reaction had been disbelief.

“It has to be a navigation error,” one colonel said, staring at reports in a smoky operations room. “No American fighter can have that range. The P-47 barely makes it to Aachen and back if it scratches its nose.”

They had learned the range of their enemies the hard way.

Bf 109s had known exactly when the Spitfires turned back in 1940. Fw 190s knew down to the minute when Thunderbolts would roll away, low on fuel and duty done, leaving the big ships to fend for themselves.

So when pilots started describing an American fighter that stayed, that still circled above Berlin as the bombers turned for home, there was a reluctance to accept it.

“Perhaps they’re P-47s with an extra tank,” one staff officer suggested.

“They’re too slim,” another replied. “And they climb. God help us, they climb.”

In a cold office in Berlin, Adolf Galland read the reports with increasing unease. He had come up through the ranks as a fighter pilot, not an armchair general. He’d flown the Bf 109 in Spain, over France, over Britain, and he knew the feel of air and the face of a foe.

He frowned at a squadron’s combat report.

New American Jäger type, possibly all-metal, laminar wing. Superior climb rate. Identified by characteristic under-belly radiator and bubble cockpit in some variants. Capable of pursuing us beyond target area and toward our bases.

The Mustang was being cataloged, measured, hated.

“You sound almost impressed,” the officer beside him said.

Galland didn’t answer immediately.

“We ignored it when they put our tanks on their bombers and flew them farther than they had any right to,” he said finally. “It seems we have made the same mistake with their fighters.”

If you were one of the men in the belly of a B-17, none of that mattered as much as what you saw out of a plexiglass window.

Joe Keller—whose bomber had almost fallen out of the sky over Schweinfurt—flew again in early 1944. This time, he noticed something different.

“Fighters!” someone yelled over the interphone as black specks appeared above the bomber stream.

Joe snapped his head up from the radio, fingers freezing on the key. He grabbed his gun and looked out. His stomach did that old familiar lurch.

Then, from above, sleek shapes dropped—not toward them, but toward the Germans.

For a fraction of a second, adrenaline made him tense. Enemy?

A Mustang flashed past, so close he saw the pilot’s face, scarf flapping, eyes narrowed. The American fighter dove straight into a clump of 109s that had been forming up, guns winking. A 109 exploded, breaking apart like someone had smashed a model plane against a table.

The Mustang pulled up, rolled, came around again. Behind him, more of them, their silver wings slashing across the morning sun.

Joe realized his shoulders, tensed for months of missions, had dropped a fraction. He felt like someone had just stepped into a bar fight at his side.

He wasn’t alone anymore.

On mission after mission, bomb group after bomb group began marking a difference in their logbooks. Before P-51 escort: nine planes lost. After P-51 escort: two, maybe three. Sometimes none.

Math had a way of cutting through fear.

The Mustang changed the way German pilots felt about their own sky.

In early 1944, Johannes Steinhoff, a tired man in a worn flight jacket with a face that had seen too much, sat on the edge of a bunk writing in his journal. Outside, the freezing air gnawed at the edges of the hangar. Inside, half his squadron was asleep, half playing cards. All of them were listening for the phone.

He wrote slowly, the words scratching at paper like a confession.

The new American Jäger, the long-range one, has altered everything. We no longer know where it will appear, or when. Our airfields, once sanctuaries, now feel exposed. We see their contrails far to the west and know: they will still be with the bombers when those bombers leave. We used to choose the time of combat. Now, combat chooses us.

He paused, eyes going distant.

I have flown perhaps 700 missions now. I have survived through skill and luck. But I look at the youngsters arriving from the training schools, with their 50 hours of flight time, and I send them up to face pilots with 200 hours of training in machines that can stay over our territory as long as they like. It feels… unfair in a way that has nothing to do with chivalry. We are being out-produced, out-trained, and now, it seems, out-flown.

Steinhoff was not prone to exaggeration.

One of his contemporaries, Eric Hartmann—black tulip on his 109’s nose, 352 kills to his name—had a more visceral memory.

He later told an interviewer that battling P-51s in 1944 felt like “boxing in a room where the walls kept moving closer. You could slip one punch, maybe two, but eventually there was nowhere left to go.”

For men whose identity was built around mastery of the air, that sense of confinement, of inevitability, was perhaps the cruelest wound.

On June 6th, 1944, as Mustangs patrolled over Normandy, a young Luftwaffe recruit named Peter strapped into a worn Bf 109 on a grass strip in France.

He had, by his own count, forty-two hours of flying time. Two flights firing his guns. No combat experience. His instructor had shaken his hand that morning and said, “Don’t try to be a hero. Just survive.”

Peter had nodded bravely and then promptly had to run around the back of a hangar to vomit.

He’d grown up on stories of the Battle of Britain, when German planes had blackened the skies. Those stories felt like ancient myth now.

He took off, stumbled through formation flying with half a dozen other equally green pilots, and climbed into a sky already thick with contrails.

For a few minutes, he saw nothing but cloud and smoke.

Then his radio exploded with panic.

“Feindliche Jäger! Feindliche Jäger überall!”

He peered over his shoulder and saw them. Silver shapes, too many to count. Some diving. Some climbing. All around the edges of the German formation.

He never saw the Mustang that killed him.

His instructor later described watching Peter’s 109 simply disintegrate, a brief flare of flame, a canopy spinning away, no parachute.

The Mustang gave veterans like Steinhoff something to fight, to match their skill against—with diminishing success—but it made boys like Peter expendable.

After the war, in calm rooms where the only sound was the clink of coffee cups and the mutter of translators, men who had tried to slaughter each other talked about airplanes.

At a symposium in the 1960s, a German former fighter commander admitted what none of them had wanted to say while the war was still raging.

“When the P-51 arrived in numbers,” he said, “we understood that the Americans had married their industry to their tactics in ways we could not copy. It was not just the aircraft. It was the training, the fuel, the spare parts, the pilot rotation. We were using up our best men to kill their young ones. They could afford it. We could not.”

He stirred sugar into his coffee.

“For us, the P-51 symbolized that imbalance. It was the visible edge of a vast machine.”

An American pilot sitting across from him smiled wryly.

“Funny,” he said. “For us it was just… the thing that finally meant we might live long enough to go home.”

They both laughed, that strange laughter veterans share when the only alternative is something darker.

In an attic somewhere in Germany, a box sits on a shelf. Inside are brittle letters, a black-and-white photograph of a young man in Luftwaffe blue standing beside a 109, and a page torn from an old journal.

The journal entry reads:

14 October 1943: Today I saw the sky filled with bombers. Hundreds. And new fighters with them, ones that did not turn back. In that moment, I knew the war was changing. We could still shoot them down. We did. But for each one that fell, more came. These new fighters, the long-range Mustangs, are like wolves that have learned to follow the herd into our own forest. I fear we will not be able to dislodge them.

On another continent, in a drawer in a quiet American house, there’s a Medal of Honor citation on yellowed paper, beginning with the words:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty…

It tells, in formal language, what James Howard did on January 11th, 1944. It does not capture the taste of fear in his mouth or the way his hands shook slightly when he lit a cigarette after landing, or the fact that he could not remember how many times he’d dove into that maelstrom, only that it always felt like once more might be too many.

What links those two artifacts—a German pilot’s note and an American pilot’s citation—is a machine and what it represented.

The P-51 Mustang did not end the war alone. No weapon ever does.

But to the men in the cockpits, on both sides of the gunsights, it was a turning point made metal. For the Americans, it was the promise of reaching home again. For the Germans, it was the realization that their sky, once so fiercely guarded, was no longer theirs.

And on that cold January day when one Mustang refused to leave and a skyful of bombers made it home, the Luftwaffe began to understand that the war in the air had moved beyond anything courage or skill alone could salvage.

From then on, every time a German pilot scanned the high altitudes and saw sleek shapes sitting comfortably above the bombers, he knew their name.

Mustang.

News

(CH1) German Pilots Laughed at the P-51 Mustangs, Until It Shot Down 5,000 German Planes

By the time the second engine died, the sky looked like it was tearing apart. The B-17 bucked and shuddered…

(CH1) October 14, 1943: The Day German Pilots Saw 1,000 American Bombers — And Knew They’d Lost

The sky above central Germany looked like broken glass. Oberleutnant Naunt Heinz had seen plenty of contrails in three years…

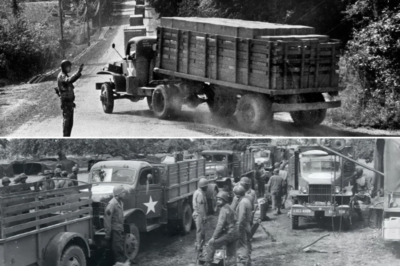

(CH1) German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

The first thing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl noticed was that the numbers, for once, were comforting. For weeks now, the war…

(CH1) German Teen Walks 200 Miles for Help — What He Carried Shocked the Americans

The first thing Klaus Müller remembered about that October afternoon was the sound. Not the siren—that had been screaming for…

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Couldn’t Believe Americans Spared Their Lives and Treated Them Nicely

May 12, 1945 – Kreuzberg, Berlin The panzerfaust was heavier than it looked in the training pamphlet. Fifteen-year-old Klaus Becker…

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

June 4th, 1943 – Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. The ship’s gangplank creaked. The air tasted like coal dust and salt….

End of content

No more pages to load