In the spring of 1944, deep inside a smoky office in Berlin, German intelligence officers spread photographs, intercepted messages, and reconnaissance reports across a long conference table. They were not assembling a picture of Allied supply lines. They were not mapping all of Eisenhower’s armies.

They were hunting one man.

His name was George S. Patton, and the Germans were spending more time trying to figure out where he was than on any other Allied commander. Not Eisenhower, who commanded the entire Allied expeditionary force. Not Montgomery, who had chased Rommel across North Africa. It was Patton who consumed their attention.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, senior German commander in the West, had issued the standing order: Any information about Patton’s whereabouts is high-priority intelligence. Reconnaissance notes with his name on them moved faster up the chain of command. Radio intercepts mentioning him were translated first. Rundstedt had fought British and French generals in one war, British, American, and Soviet commanders in this one. He respected many of them.

Patton frightened him.

First Contact: North Africa

The Germans got their first real look at Patton in November 1942, when American troops made their first large-scale landings in Operation Torch. Patton commanded the Western Task Force, 35,000 Americans pushing onto the coast of Morocco.

The US Army had a reputation. New to the war. Slow. Methodical. Dependent on overwhelming artillery rather than daring maneuvers. German staff officers expected a heavy-footed opponent, one they could study and counter at leisure.

Patton did not fit that picture.

In three days, his troops had fought their way to Casablanca, forced a French surrender, and secured their objectives. German observers in the region sent back reports that didn’t match their assumptions: “American general Patton moves with unusual speed”…”Force advances faster than expected”…”Local resistance collapses under pressure.”

The name went into their files, highlighted in red.

Who was this man?

Berlin Intelligence dug deeper. The reports that came back were unsettling. Patton, they learned, had been studying German doctrine for years. He read German military writings in German. He had walked the battlefields of the First World War, tracing the routes where German armies had nearly broken the Allied lines. He talked about mobile warfare and armored thrusts the way their own Panzer generals did.

He understood the German way of war—

sometimes better than German officers who had grown up in it.

Kasserine: He Turns a Rout into an Army

In February 1943, German and Italian forces under Rommel smashed into green American units at Kasserine Pass in Tunisia. The result was a disaster. The 2nd US Corps broke and ran. Guns were abandoned, positions overrun, command structure shredded.

Rommel wrote that American soldiers were brave individually but poorly led and badly coordinated. In Berlin, officers nodded. The Americans hadn’t fought a continental war in a generation. This, they thought, was what they expected.

Then they watched what happened next.

Three days after the Kasserine debacle, Patton took command of II Corps.

German intelligence watched the same units they’d just routed suddenly behave like a different army. Discipline returned overnight. Stragglers were rounded up. Patrols became sharper, more dangerous. Within two weeks, those same troops were attacking German positions with energy that surprised even British units that had fought alongside them.

Field reports mentioned it: “The Americans have a new commander. They are no longer the same opponents.”

Rommel, no stranger to audacity himself, noted that the Americans under Patton had become “fast, flexible, and aggressive.” The change hadn’t come from new equipment or reinforcements. It had come from one man’s command style.

The Germans took note: this was not a predictable enemy who needed months to recover from a defeat.

This was someone who could turn collapse into counterattack in a matter of days.

Sicily: Racing Through the Island

In July 1943, Allied forces invaded Sicily. The plan was straightforward on paper. Montgomery’s British Eighth Army would lead the main push up the eastern coast toward Messina. Patton’s newly formed Seventh Army would protect the left flank.

Patton had different ideas about “protecting the flank.”

From the moment his troops hit the beaches, he drove them like a cavalry commander, not a cautious infantry general. He exploited every weakness, every gap, pushing units across the island at breakneck speed.

His columns took Palermo in ten days. They freed the western half of the island while German units, expecting a slower Allied advance, scrambled to set up defenses that Patton was already flanking.

In Berlin, German staff officers read the reports with disbelief. One after-action note from a German division commander sounded almost admiring: “Patton’s army maneuvers with the tempo of a Panzer formation. He throws his forces forward without the delays we expect of Americans.”

Most astonishingly, Patton reached Messina before Montgomery—despite starting farther away and being assigned a secondary role on paper. To German planners, that said everything. Here was an American general who attacked like a German—a good German. He was breaking their own rules against them.

They’d spent years telling each other that Americans could not conduct true mobile warfare.

Then Patton drove an entire army across a mountainous island in 39 days and proved them wrong.

The Slapping Incident: A Gift That Wasn’t

At the height of his new fame, Patton did something that nearly got him removed from the war.

Visiting two field hospitals in Sicily that summer, he walked among wounded men—those he called “his boys.” In two separate incidents, he encountered soldiers suffering from what we now call PTSD and what then was vaguely understood as “battle exhaustion.”

To Patton, there was no such thing. A man wearing a uniform should be on the line. He slapped one soldier. Days later, he slapped another, even drawing his pistol. Word got out. Eisenhower was furious. The American press, when they finally learned, published outraged stories. Some congressmen wanted Patton sent home in disgrace.

German intelligence followed every twist of the scandal.

They could hardly believe their luck. The most aggressive, instinctive American commander might destroy his own career with his temper. Reports to Berlin were almost gleeful: “Patton reprimanded by Eisenhower…subject of political scandal…possible dismissal.”

But Eisenhower, who understood the value of Patton’s abilities all too well, did not fire him. He removed him from immediate field command, forced him to apologize, and then quietly kept him on the bench.

German analysts read that detail and fell silent.

Patton might be sidelined now, but if the Americans were keeping him in reserve, it meant they were saving him for something important.

That single decision would haunt them a year later.

The Phantom Army: Patton as Decoy

By early 1944, with the invasion of Europe approaching, Patton found himself in England without a field army to command. On paper, that made no sense. German intelligence refused to accept it.

They assumed—as any professional would—that the Allies would put their most dangerous general in charge of their most important operation. So when their reconnaissance and radio intercepts pointed to something called First United States Army Group (FUSAG), based in southeast England and apparently commanded by Patton, they drew a natural conclusion:

Where Patton was, the main invasion would strike.

Everything they saw confirmed this. Radio traffic. Dummy tanks (they didn’t know they were rubber). Inflatable aircraft. Fake landing craft. Headquarters buildings with lots of comings and goings.

They believed it.

FUSAG was a ghost army. A deception. A giant stage set erected across Kent and Sussex. Its job was to convince the Germans that the real invasion would come across the shortest point of the Channel—at Pas-de-Calais. And because Patton was “in command,” it worked.

When D-Day came on June 6th at Normandy, 150 miles away from Calais, German commanders hesitated. Field Marshal Rommel was away. Rundstedt wanted to commit the Panzer reserves immediately to throw the Allies back into the sea. But Berlin stalled.

Could this be a diversion? Was Patton about to land the real blow at Calais?

For six crucial weeks after the Normandy landings, German armored divisions—some of their best—sat near Calais waiting for Patton’s phantom army. They remained fixed in place while American, British, and Canadian forces clawed their way off the beaches and into the bocage.

Patton didn’t fire a shot in that part of the war. He didn’t have to.

His reputation pinned down entire Panzer divisions.

Third Army Unleashed: The Breakout

On August 1st, 1944, the waiting ended. Patton was given command of Third Army, unleashed into the breakout from Normandy.

To German intelligence, it was like watching a dam burst.

Once his units punched through the German line at Avranches, they poured into the open countryside of France. Patton loved open ground. It let him do what he did best: move fast and hit hard.

Third Army advanced up to 50 miles a day. Town names poured into situation reports: Le Mans. Chartres. Orléans. They bypassed pockets of resistance, left them to follow-on units, and kept driving. German forces who tried to set up a new defensive line found Patton’s tanks and armored infantry already in their rear.

Rundstedt’s staff complained that their maps were worthless by the time they were printed; Patton was outrunning them. The Third Army’s spearheads became known to German troops as “fire brigades”—appearing wherever the line seemed thin, spraying destruction, then vanishing again in dust.

In mid August, Patton turned that speed toward strategic effect. Near the town of Falaise, retreating German forces were funneling through a narrow gap as they tried to escape encirclement. Patton’s divisions drove north while Canadian and Polish forces attacked from the other side.

The trap closed.

Inside, German units dissolved. Thousands were killed, tens of thousands captured. The roads were clogged with burned-out trucks, smashed artillery, dead horses, and abandoned tanks.

One German officer, who managed to escape on foot, later described it like this: “We were not an army anymore. We were a mob, and Patton was the butcher.”

The German army in France ceased to exist as an effective fighting force in just a few weeks. Its equipment was gone. Its men dead or captured. Its generals humiliated.

They had underestimated Patton yet again.

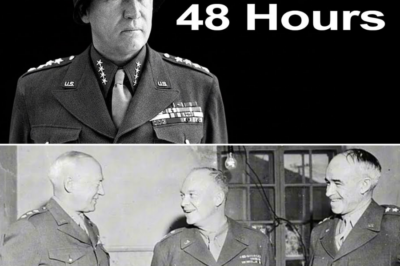

The Bulge: 48 Hours

In December 1944, the Germans did something no one expected: they attacked.

Hitler launched his last great gamble through the Ardennes—a massive offensive intended to split the Allied lines, capture the port of Antwerp, and force a negotiated peace in the West.

The Battle of the Bulge began with fog, snow, and surprise. American units in the quiet Ardennes sector were overrun. Communications broke down. The 101st Airborne Division found itself surrounded in the road hub of Bastogne.

Eisenhower called his commanders to Verdun.

The mood in that room was grim. Maps showed a huge German salient jutting westward. Eisenhower didn’t mince words. The situation was dangerous. Then he asked the only question that mattered:

“How soon can someone attack north to relieve Bastogne?”

The answers came back hesitantly. Weeks, most said. They’d have to disengage, reorient, move supply lines. The weather was terrible.

Patton said: “I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours.”

The room went still. Some thought he was joking. Others assumed he was showing off, as usual. It was impossible. An army is not a sports car. You don’t just turn the wheel and go.

But Patton had already done the hardest part. For days before the offensive, his intelligence chief, Oscar Koch, had warned him that German troop movements suggested something big brewing in the Ardennes. High command dismissed the warning; they believed Germany was on the ropes and incapable of such an effort.

Patton listened.

He quietly ordered his staff to prepare contingency plans: three different options for pivoting Third Army north on short notice. Routes. Timetables. Fuel dumps. Signal plans.

So when Eisenhower asked his question at Verdun, Patton wasn’t making a wild promise. He was giving a timeline for plans that already existed.

He left the meeting, picked up a field phone, and gave the code phrase: “Play ball.”

Third Army began to turn.

In snow and ice and under low clouds, more than 250,000 men and thousands of vehicles wheeled 90 degrees and started moving. They drove day and night over narrow roads, through villages, around stalled traffic, through conditions that froze oil and killed men in their foxholes.

On December 26th, tanks from Patton’s 4th Armored Division broke through to Bastogne.

The Germans had never imagined an American army could pivot so fast. Their offensive timetable depended on the Allies needing at least a week to muster a response.

Patton did it in four days.

“The General We Feared Most”

After the war, Allied officers sat down with captured German generals and asked them to evaluate their opponents. It was a professional courtesy among career soldiers: who did you respect, who did you mistrust, who did you fear?

Again and again, they named Patton.

Montgomery, they said, was cautious. Predictable. “One could prepare for him.” Bradley was competent but methodical. “One could foresee his actions.”

Patton was different.

He moved too fast. He took chances they themselves might have taken ten years earlier, when their own army was young and audacious. He attacked before they believed he had the supplies. He maneuvered where they assumed the terrain was impossible. He didn’t wait for perfect conditions.

He forced them to play his game.

Field Marshal von Rundstedt called him “the most dangerous of the Allied generals.” General Fritz Bayerlein, veteran Panzer commander, said Patton was “the only American general who understands mobile warfare.”

They recognized, uncomfortably, a mirror of their own ideal.

He thought like a German Panzer commander—only now he commanded the side with more tanks, more planes, more fuel.

From Casablanca to Kasserine, from Sicily to Falaise, from Normandy’s hedgerows to the Ardennes forests, the pattern held. Patton broke their assumptions and then broke their lines.

It wasn’t that German generals believed Patton was invincible. They defeated him tactically at times, delayed him with weather and logistics, outmaneuvered him in patches.

But as an opponent, he forced them into constant crisis. Into reacting. Into doubting.

And in war, that’s often the beginning of the end.

In the spring of 1944, those German intelligence officers in Berlin stared at their maps and photos, at reports of dummy armies and real ones, trying to answer a question that would shape the fate of Europe:

Where will Patton strike next?

They had learned one thing the hard way: wherever he was, that was where the real danger lay.

George S. Patton never commanded all Allied forces. He never wore the title Supreme Commander. But in the minds of his enemies—the men who had rolled across Europe behind their own blitzkriegs—he was the one they feared the most.

Not because he was loud or theatrical, though he was both.

Because he fought their war better than they did.

And because, from the moment he arrived in North Africa until the last German unit laid down its arms, he refused to be the kind of enemy they thought they understood.

News

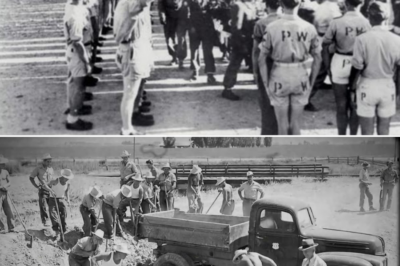

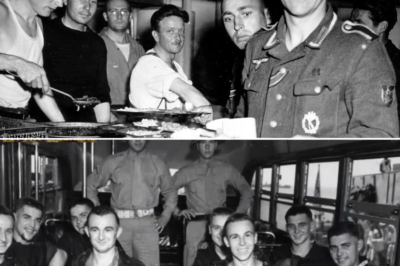

(CH1) The German POWs Mocked America at First—Then They Saw Its Factories

When the train slid to a stop in Norfolk in January 1944, the men inside braced themselves for the worst….

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

By the time the hatch slammed shut on the Liberty ship and the Atlantic swells began to lift the hull,…

(CH1) “It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

By the time the trucks pulled up to the gate at Camp Swift on May 12th, 1945, Texas heat had…

(CH1) The German POWs Laughed at American Food—Then They Ate in US Camps

They had laughed at America long before they ever saw it. Around smoky campfires in Russia and under low tarpaulins…

(CH1) Why Patton Was the Only General Ready for the Battle of the Bulge

On the night of December 19th, 1944, in a converted French army barracks at Verdun, the air in the conference…

(CH1) “He Gave Me His Blanket” — How a Frozen American Soldier Saved a Little Girl in the Ardennes

On the night of December 22nd, 1944, the Ardennes forest seemed to have turned entirely to ice. Snow swallowed the…

End of content

No more pages to load