The Day the Monsters Had Rules

Schroenhausen, Bavaria

April 1945

The engines came first.

Margaret Miller pressed her forehead to the cracked pane of the upstairs window and listened as the sound grew—low at first, a distant growl, then louder, heavier, like thunder rolling uphill.

American tanks.

She’d heard them in newsreels once, big and ugly and unstoppable, framed by speeches about barbarian invaders.

She’d seen the posters, too.

American beasts with ape arms, teeth bared, fists wrapped around terrified German women. The announcer’s voice on the radio had made it sound like a law of nature: They will come. They will destroy. They will do to you what we did to them.

She’d believed him.

It was not hard to believe, after the last few years. They’d watched their own side burn villages and shoot civilians and call it necessary. Margaret had changed bandages on soldiers who came back from the East with their eyes hollow and vaguely pleased, talking about “teaching them a lesson.”

If those were the things your own men did, what would the enemy do when they finally reached you?

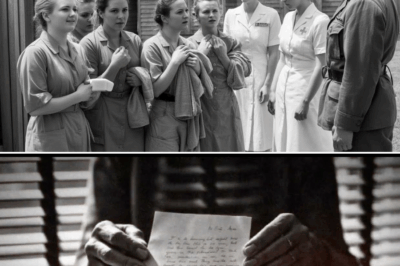

That morning, Margaret had been summoned to the town hall.

The Bürgermeister stood in the cellar with a stack of papers and a face that had gone from florid to gray in two weeks.

“You have been chosen,” he said, hands folded behind his back.

Eight young women stood in front of him. Margaret recognized them all—girls from school, from choir, from the baker’s queue.

“To do what?” asked Helga, the boldest of them.

The Bürgermeister looked at the floor.

“To… serve the victors,” he said. “To protect the other women in the town.”

None of them needed the word he didn’t say.

Comfort.

The syllables lodged in Margaret’s throat like a stone.

The regime that had told them they were the purest daughters of the Reich now lined them up in a damp basement to be offered like hush money.

“Surely…” Elsa whispered, voice squeaking, “surely they cannot mean…”

The Bürgermeister cut her off sharply.

“It is decided,” he said. “It is better that a few suffer than that all suffer. This way, the Americans will leave the rest alone.”

Margaret clutched the small cloth bag she’d brought—two changes of underclothes, a comb, the little photograph of her parents she’d salvaged from the rubble after the last air raid. In the side pocket, tucked into a scrap of paper, was the cyanide capsule the pharmacist had pressed into her hand the day before.

“If the stories are true,” he’d said, eyes too bright, “you may not want to see tomorrow.”

Now, sitting on a hard wooden bench in a town hall cellar that smelled of damp stone and fear, she believed him.

Upstairs, the engines grew louder.

Someone sobbed.

Margaret took the cyanide out once, turning the tiny glass vial between her fingers.

Better to choose, she thought, than be… chosen.

Then she shoved it back into her pocket.

She wasn’t ready.

She’d never be ready.

The tanks rolled into Schroenhausen at midday.

She expected screams.

She expected gunfire inside houses, boots on stairs, doors kicked in.

What she heard instead, from behind the thick cellar door, was… voices.

Male. American, by the accent—harsh R’s, lazy vowels.

Orders.

“Squad two, on me. Check that building. Nobody alone. Stay in pairs. You know the rules.”

Boots crossed above them.

The cellar door rattled once.

Margaret flinched.

Then the bolt slid back.

She swallowed hard and gripped the vial in her pocket.

The door opened.

Light spilled in, blinding after the dim.

Silhouetted in the doorway was a figure in a helmet and an American uniform. His rifle was slung over his shoulder, barrel pointed down, hands visible.

Beside him stood… a woman.

American, by the uniform. Red cross on her sleeve.

She stepped forward.

Her German was halting but understandable.

“Wer sind Sie?” she asked. “Who are you?”

No one answered.

“What is this?” the soldier asked in English.

Margaret didn’t understand the words, but she understood the tone—confusion, not hunger.

The Bürgermeister, pale as paper, stepped forward.

“Sie sind… für Ihre Männer,” he stammered. They are for your men.

The American’s face went hard.

“For our what?” he snapped.

The medic’s lips tightened.

She turned to the Bürgermeister.

“No,” she said in German, the word sharp. “This is… wrong. These women go home.”

He blinked.

“That is… impossible,” he said weakly. “The orders—”

“Our orders,” the American cut in, “come from General Eisenhower. Fraternization verboten.” He mispronounced the last word, but the meaning hit Margaret like a slap.

Forbidden.

The American pulled a small booklet from his pocket and snapped it open.

On the cover, in neat black letters, were the words: Pocket Guide to Germany.

He flipped to a page and jabbed his finger at a line for the medic and the Bürgermeister to see.

“The German woman is not your prize,” he read slowly, then looked up. “That’s what it says. In case there was any confusion.”

Margaret stared.

He was quoting from a book.

About rules.

About not touching them.

The medic stepped fully into the room now, scanning the faces.

“You can go home,” she said. “Nach Hause. Directly.”

No one moved.

“This is not a trick,” she added, as if aware of how unbelievable it sounded. “The war is almost over. We do not… take women.”

Margaret’s knees nearly gave way.

The vial in her pocket suddenly felt absurd.

“We were told…” Elsa blurted, “…you would… hurt us.”

The medic’s mouth twisted.

“We were told a lot of things, too,” she said. “Some were true. Some weren’t. This is true: If you go home now, no one in my unit will follow. You have my word. That is… alles, was ich sagen kann.”

All I can say.

The women looked at each other.

One laughed, a short, hysterical burst.

Then one by one, as if testing thin ice, they stepped past the cellar threshold into the hallway.

No one grabbed them.

The soldier stepped back to make room, fingers loosely around his rifle, barrel still pointed at the ground.

Margaret waited until she was the last.

When she reached the door, she paused.

The American—not much older than she was, she realized now saw his face—met her eyes.

“Ma’am,” he said in English, with the same respectful tone she’d heard them use with their own nurses.

She edged past him, heart hammering.

She expected to feel hands on her.

She felt only air.

Outside, the tanks sat in the main square like huge, ugly dogs that had been ordered to “stay.” Soldiers moved around them in pairs, always within sight of each other.

No one lingered under windows.

No one leaned in doorways watching the girls spill into the street.

An officer with a clipboard was talking to her neighbor, Frau Weber, who had three daughters barely younger than Margaret.

“This room remains private,” he was saying, gesturing toward a closed door in the house. “Nur für Ihre Familie. Only for your family.”

The translator repeated the words.

He pointed to another room.

“Here, we sleep. We bring our own food. We lock this door. You lock yours.”

He said “lock” like it was a promise.

Frau Weber blinked.

“You won’t…” she fumbled “…take my girls?”

The officer’s expression tightened.

“No,” he said. “Our orders are clear. Frauen bleiben in Ruhe. Women are to be left alone.”

He made a note on his clipboard, had her sign at the bottom.

“There,” he said. “Paper. If any man bothers your daughters, you tell the Kommandantur. They will see this.”

He tapped the signature.

He was building a wall out of forms.

Margaret watched, numb.

She’d spent years being told the Americans were coming to do what German soldiers had done in Poland, in France, in the Soviet Union. That they were wolves.

These wolves were asking permission to sleep on the floor.

The first few nights, she still slept with the cyanide capsule under her pillow.

Habits didn’t evaporate just because reality refused to match the story.

She listened for screams.

For cries in the night.

What she heard instead was boots on patrol, the occasional bark of a dog, a jeep’s engine.

The Americans came and went in twos.

They carried their rifles like tools, not trophies.

They ate in the schoolhouse, not at local tables, and when they requisitioned food, they left receipts that said things like “two sacks potatoes” and “four loaves bread” instead of just leaving emptiness.

They posted curfews.

They posted rules.

They enforced them.

She heard, weeks later, that a soldier from the next town over had been court-martialed for being caught alone with a German woman after curfew.

“Forty-one already,” the American chaplain said, reading a memo and shaking his head. “Eisenhower wasn’t kidding about making examples.”

The news went around faster than any leaflet.

Not even the Americans were allowed to treat German women the way everyone had expected.

In another town, not that far away, on the other side of what would soon be called the line, Soviet troops rolled in.

They did not bring booklets.

The rumors that came back from there were… worse than any propaganda Margaret had heard about the Americans.

Far worse than the posters. Not exaggerated.

She thought of the cellar again. Of the vial in her pocket. Of the medic’s firm, tired face.

Somewhere between the Missouri National Guard and the town hall steps, two versions of what defeat looked like had diverged.

She’d landed in the one where the men had signed pledges not to treat her as spoils.

It changed everything.

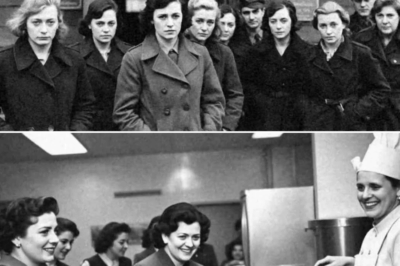

At first, the American rules were ironclad.

No private conversation.

No letters without inspection.

No more than five minutes of talking to the same civilian without a second soldier present.

No German women in military vehicles.

No German women in the barracks. Ever.

The Germans watched them move through the town like figures behind glass.

By summer, some of the glass thinned.

Children were allowed to sit on jeeps in the square during quiet hours, as long as their mothers watched. Boys listened to American stories about New York and Chicago. Girls laughed at their accents.

In the fall, Margaret saw flyers posted on the town hall bulletin board: Gesucht: Übersetzerinnen—wanted: female translators. The Americans needed secretaries who could speak both languages.

She went.

She’d always been good with words.

The office in the old mayor’s building was a strange mix of uniforms and civilian dresses, typewriters clacking in English and German.

She sat at a desk opposite an American sergeant named Tom Wilson, who dictated letters to Munich while she translated, both ways.

“You’re very fast,” he said once, impressed.

She shrugged.

“The Nazi party taught us typing before they taught us anything else,” she said dryly. “I might as well put it to better use now.”

He grinned.

“Glad to help repurpose your skills,” he said.

He was kind.

He made sure his coffee pot was full.

He brought chocolate once a week to share with the office staff.

He never closed the door when it was just the two of them.

Not because he feared her.

Because he respected his own rules.

She noticed.

So did every other German woman in that room.

Every conversation like that chipped away at the thing propaganda had built between them.

By Christmas, she found herself humming an American carol under her breath at the same time she peeled potatoes for a soup kitchen run by the U.S. Army and the local pastor together.

The Reich had told her the Americans would destroy Germany.

They were… rebuilding it.

With ration forms and Marshall Plan proposals and dull meetings that lasted hours and ended with the sudden appearance of a bag of oranges in the office.

What destroyed Germany was the same thing that had decided girls in Schroenhausen’s cellar were expendable.

That had been German.

Years later, in ’55, when Margaret signed Margaret Wilson at the bottom of a memo as a liaison for the Marshall Plan, she paused for the briefest moment over her maiden name in her head.

Margarete Müller.

She could still see herself in the mirror of that cellar, cheeks smudged, braids coming loose, hand clenched around a glass capsule.

She could still hear American boots on stairs.

Could still hear the medic’s German, awkward and clear.

“You can go home.”

She’d gone farther.

Across an ocean, across a language, across a border that ran straight through her old life.

She married Tom.

Not because he’d rescued her.

He hadn’t.

He’d simply done what his pocket guide and his conscience told him to.

She married him because over months and years of shared files and bad coffee and decent jokes, she discovered that beneath the uniform was a man who believed in rules even when no one was looking.

Who thought “respect” was something you owed people before they earned it.

Who, when she told him about the cellar, had gone white and said, “We had no idea—that they were planning… that.”

“You didn’t do it,” she’d said.

“I would’ve killed a man under my command who tried,” he’d replied, fierce. “That’s the difference, I think.”

She’d nodded.

They’d built their life in a world the Reich had called impossible—German and American, equal, messy, arguing over whose traditions their daughter would follow and whose holidays to visit.

Their daughter grew up bilingual.

She played with American and German kids in streets that hadn’t seen tanks in years.

She wrote school essays about “My two homelands” and turned in reports on what her mother remembered about the war.

“In April 1945,” Margaret told her once for a homework assignment, “I sat in a cellar and waited to be hurt. They told us we had no choice. The men who came through the door gave us one anyway.”

“So the Americans weren’t monsters?” her daughter asked.

“Some were,” Margaret said honestly. “There were crimes. There were bad men. But most…” She thought of the medic. Of the officer with the clipboard. Of Tom, with his careful distance and his clumsy German. “…most were human. And that,” she added, “was what the Nazis never warned us about. Because if you admit your enemy is human, the whole story starts to fall apart.”

Her daughter chewed on her pen.

“So democracy won because… it behaved better?” she asked.

“In part,” Margaret said. “Bombs ended the fighting. Behavior ended the fear.”

She didn’t romanticize occupation.

There were shortages and black markets and arguments and mistakes.

But when she thought of the line where her life bent away from what might have been, it wasn’t a date on a treaty.

It was a pair of boots at the top of a staircase.

A red cross on a sleeve.

A man reading from a booklet and saying, “The German woman is not your prize.”

The end of a war wasn’t just the silence of guns.

Sometimes, it was the silence of doors that never opened the way you’d been taught to dread.

Margaret kept the cyanide vial in a drawer for years.

She never used it.

Eventually, she threw it away.

By then, she had something the Reich had never offered her:

A life not built on fear.

The little American booklet had promised soldiers that how they behaved would help “win the peace.”

No booklet could have predicted a girl in a Bavarian cellar holding it up as proof, decades later, that right and wrong hadn’t been abstract terms.

They had been boots and orders and distance.

Propaganda had tried to teach her what monsters looked like.

Reality had shown her something far more subversive:

Men who could have done their worst—

And didn’t.

Sometimes, she’d think, that’s all it takes to pull the teeth out of a lie.

Not grand speeches.

Just a knock on a door, a hand held back, and the words:

“You can go home.”

THE END

News

Amidst the chaos, they set up a makeshift aid station in a church displaying a prominent red cross, treating wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict.

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

My husband left us for his mistress—and three years later, I met them again. It was unbelievable, but satisfying.

After 14 years of marriage, two children, and a life I thought was happy, everything collapsed in an instant. How…

The Dishwasher Girl Took Leftovers from the Restaurant — They Laughed, Until the Hidden Camera Revealed the Truth

Olivia slid the last dish from a large pile into the sanitizer and breathed a sigh of relief. She wiped…

German Women POWs in Oklahoma Were Told to Shower With Water — And Burst Into Tears

Story title: The Day the War Fell Off Their Skin Camp Gruber, Oklahoma April 1945 The truck came in on…

“Are There Left Overs?” Female German POWs Were ASTONISHED When They First Tasted Biscuits and Gravy

Story title: Biscuits and Mercy Camp Somewhere in the American Midwest Late 1944 The first thing they noticed was the…

When A German POWs Women Married To An American Soldier.

Story title: Paper Walls March 1946 Fifteen miles south of Fort Dix, New Jersey The morning came in wrapped tight,…

End of content

No more pages to load