Part 1 – Names on the Fence Line

The desert gave them up the way it gave up everything else: slowly, grudgingly, without drama.

General Reinhardt Keller squinted into the white North African sky as the column of prisoners trudged toward the trucks. The light was so harsh it scraped color out of everything—the sand, the trucks, the faces of men who only a week ago had been calling in artillery with the certainty of people who believed the war could only end one way.

Their way.

Now the only maps Keller could see were in his memory. Arrows that had once driven toward Alexandria, then bent back under British pressure. Thin supply lines stretching from Tunisia to Tripoli, cut again and again by Allied aircraft. Fuel gauges dropping toward zero, artillery shells stacked in ever smaller pyramids.

Surrender, when it came, had felt less like a decision than like gravity.

No last stand. No heroic final charge. Just a quiet arithmetic: fuel gone, ammunition thin, no relief in sight. The desert had swallowed their options and offered up their bodies in exchange.

As he climbed into the back of the American truck, Keller glanced at the other officers.

General Matthias Vogle, ten years younger and half a head shorter, stared straight ahead, his expression caught somewhere between anger and disbelief. Behind him, Colonel Hartmann’s jaw worked, as if he were chewing on a curse he couldn’t quite spit out.

Around them, desert wind lifted thin veils of sand that settled on boots, trousers, the cuffs of uniforms that still carried rank insignia the Americans hadn’t bothered to strip. Not yet.

The engines roared. The convoy moved.

Someone at the tailgate muttered, “Where will they take us?”

“England,” another guessed. “Canada, perhaps.”

“Let them,” Hartmann snorted. “The Reich will still be there when we return.”

Keller said nothing. He kept his hands folded on his knees and watched the desert recede.

He had spent his life learning to interpret terrain. The color of soil. The way water cut through valleys. How railways bent toward cities. North Africa had been an alien map at first, but he had learned its language. It was a place of edges—coast and sand, lifeline and emptiness.

Now, as the trucks rolled toward waiting ships, Keller had the uneasy sense that he was about to fall off the edge of the world.

The ocean smelled different than he’d imagined.

In German training films, the sea was always gray and noble, a thing of steel hulls and white wakes. Here it was endless and indifferent. Salt, diesel, something green and alive beneath the surface.

Days blurred into nights, the ship creaking its way west. The German officers were confined to a section below deck, let up in small groups to stretch their legs under the watchful eyes of American guards.

Keller took the rail whenever they let him.

He’d grown up on riverbanks and among hills. This much openness unsettled him, a horizon with no anchor points. He found himself looking for something—anything—that would tell him where he was.

There was only sky and water.

Behind him, men talked.

They traded rumors the way soldiers always did.

“One of the Afrikakorps officers said the Americans have no discipline,” Vogle remarked one afternoon, leaning beside Keller at the rail. “It’s all machines. Money. No real spirit.”

“That officer is on this ship with us,” Keller said. “I wonder if that comforts him.”

Vogle gave a short, bitter laugh.

“Our propaganda films always show Americans as fat, soft, indulgent,” he said. “Jazz and gangsters. No backbone.”

“And yet they crossed an ocean to fight us,” Keller said quietly. “Soft men do not do this.”

Vogle shifted uncomfortably.

Others clung harder to the old stories.

“They are a rabble,” Colonel Hartmann insisted one night in the cramped sleeping bay. “A nation of mongrels. No true blood, no true unity. Once their casualties mount, they will fracture. Italians, Poles, Jews, all squabbling. They cannot match our will.”

Keller lay on the narrow canvas cot and stared at the underside of the bunk above him.

He thought of the American soldiers he’d seen in Tunisia—awkward at first, then more sure-footed as the months went on. Their artillery coordination had improved. Their armor had become faster, their infantry more confident.

Will, he’d decided long ago, was not a uniquely German commodity.

Now, in the dark, listening to the soft groaning of the ship, he wondered what that will looked like in the place they called home.

“Where do you think they will keep us?” Vogle asked later, as the ship rolled gently.

“Near the coast,” Keller said automatically. “Ports. Naval bases. Easier to guard.”

“Not in America itself?”

Keller hesitated.

“There is no reason to waste ships moving us farther,” he said. “We are officers, not secrets.”

He said it like an axiom, something that did not require proof.

So when a guard came down the next day and announced—in halting German—that they would be traveling “thousands of miles inland” once they reached the United States, Keller’s certainty cracked.

Why send prisoners into the interior?

What were they hiding there?

The first glimpse of America did not look like a military secret.

It looked like a painting.

New York—or some port that might as well have been New York—rose from the water in steel and glass, cranes and bridges, as if the land itself had decided to grow upward.

The Germans pressed against the portholes, eyes wide.

“Look at the height,” someone breathed.

“Skyscrapers,” another murmured. “We have buildings like this in Berlin, but…”

“But Berlin looks like a war,” Vogle finished grimly.

Here, the harbor seemed… intact. Ships came and went, cargo cranes moved, tugboats nudged freighters into place. There were soldiers, yes, and flags and bustle. But no bomb craters. No smoke.

As they disembarked and were marched under guard, Keller inhaled the city’s smell—salt, coal, hot metal, something sweet from a bakery they passed too quickly to see. Civilians walked the sidewalks. Women pushed prams. Children stared openly at the column of German uniforms and then were pulled gently away by their mothers.

There were no jeering crowds. No thrown stones.

Just curious glances, some hard, some neutral.

“They do not seem afraid of us,” Vogle muttered.

“Why would they be?” Keller replied. “The war is far from their homes. For now.”

Trains waited.

The Germans were loaded into cars—not cattle cars, but passenger coaches, their windows barred but not boarded. As the train pulled out, Keller watched the harbor recede, the steel forest shrinking into a line on the horizon.

Then the landscape changed.

It wasn’t just the size of the country that stunned him.

It was its… ease.

The train rattled past industrial districts: factories with tall stacks, yards full of parked automobiles, rows of houses with neat yards. Then suburbs blurred into farmland. Fields spread out in gold and green, dotted with farmhouses and red barns.

Town after town slid by, each with its own water tower, its own small station, its own tidy main street.

There were signs of war, yes—posters, military vehicles on the roads, occasional columns of troops. But the land itself looked… untouched.

The officers stared.

In Europe, by now, even places far from the front felt strained. Ration lines, bomb scars, air-raid sirens. Here, people seemed to go about their lives with a calm that bordered on indifference.

“Do they not know?” Hartmann asked, almost angrily, as they passed a playground where children chased each other under a bright blue sky. “Do they not understand what is happening overseas?”

“I think they do,” Keller said. “They simply understand it differently.”

The further west they went, the bigger everything felt.

Cities thinned out. Space expanded. Skies grew wider. Forests gave way to plains, plains to low, rolling hills.

After days that felt like weeks, the train slowed.

A word passed down the coach like a dropped stone gathering echoes.

“Texas.”

Keller rolled the syllables around in his mind. They felt strange. Soft consonants, open vowels. A place name from another world.

Out the window, the horizon stretched in a way even North Africa had not prepared him for. Pastures ran to the edge of sight, interrupted by clusters of trees and low houses. Cattle dotted fields like chess pieces. Windmills turned lazily in the heat.

The train squealed to a stop beside a modest station. When the doors opened, heat poured in—heavy, full, carrying the scent of dust and baked earth.

Not the dry blade of the desert. Something thicker, almost humid.

As Keller stepped down onto the platform, another smell hit him.

Smoke and meat.

“Barbecue,” an American guard said with a grin when one of the officers wrinkled his nose. “You’ll like it, Kraut.”

The word was meant as a jab, but there was no real venom in it. The guard sounded more amused than cruel.

Barbecue meant nothing to Keller. But his stomach tightened all the same.

They were loaded into trucks—olive drab, canvas-topped, hot as ovens inside.

The convoy rolled out, leaving the station behind.

At first, the land around them looked empty.

Then Keller started to see it.

Fences. Mailboxes. Farmhouses tucked back among live oaks. Rows of corn and sorghum, orchards of low trees he didn’t recognize. This wasn’t wilderness. It was a patchwork of lives.

Out of habit, Keller’s eyes tracked text.

Signs at the ends of driveways, painted on wood, nailed to posts.

The first one made him blink.

Schmidt Ranch

He told himself he’d misread it. Heat, dust, fatigue.

Then they passed another.

Braun Dairy Company

Another.

Keller Feed Store

He sat up straighter.

“What is it?” Vogle asked.

“Did you see that sign?” Keller said, voice low. “Keller. My name.”

Vogle snorted.

“Perhaps they heard you were coming,” he said. “Decorated the countryside in your honor.”

But his eyes started scanning, too.

The next one sealed it.

Albrecht Cattle Company

The vowels were slightly butchered by American paint, but the root was unmistakable. Albrecht, not Albert.

“I do not like this,” Hartmann muttered from behind them. “They are mocking us.”

“By naming their farms after our families?” Keller asked. “Do not be childish.”

“Then how do you explain it?” Vogle demanded quietly. “Coincidence?”

The Americans driving the trucks showed no sign they considered the signs significant. They didn’t point. They didn’t smirk. They simply bounced along the rutted road, sweat darkening their collars.

If this was theater, it was remarkably well rehearsed.

The trucks rolled through a town that looked like something out of a painting in a history book—false-front buildings lining a dusty main street, a church steeple, a small schoolhouse. An American flag hung over the post office.

Underneath the very American facades were names that made Keller’s brain stutter.

Heidenmann’s Bakery

Krauss Hardware

Mueller’s Kitchen

The S’s were sharp, the umlauts gone, but the bones of the words were his own.

The prisoners stared.

Some looked unnerved. Others looked almost offended.

“This is impossible,” Vogle whispered. “They must be copying our names. To… to play with us. To unsettle us.”

“Why?” Keller asked. “So that a handful of captured officers will feel strange for a few hours? The Americans do not run propaganda at this level of… detail.”

He trailed off.

The truth he didn’t want to speak sat behind his teeth like a hot stone: this was normal here.

The convoy rattled past a white wooden house with a big porch. A woman in a simple dress stood on the steps, shading her eyes, a child holding onto her skirt. As the trucks passed, the child waved.

Keller felt something in his chest twist.

He looked away.

The barbed wire and towers of the camp appeared almost suddenly around a bend. Olive drab mixed with raw timber, watchtowers at the corners, a gate with a guard shack. A tin sign with the camp number.

Outside the fence, a handful of locals stood watching. Men in worn hats and boots. A couple of teenagers. An older man with a weathered face, thumbs hooked in his belt.

Keller’s gaze caught the name patch on the older man’s shirt.

Keller

He blinked.

The man noticed and nodded—a small, polite acknowledgement. Not mocking. Not deferential. Just… seeing.

Reinhardt Keller, General of the German Army, stared at Henry Keller, Texan rancher, and felt the first real fissure open in the wall the Reich had built in his mind.

He was still staring as the truck rolled through the gate.

Processing was efficient.

Names, ranks, basic information, recorded by American clerks who rolled their R’s oddly when they tried to pronounce “Reinhardt.”

The barracks were wooden, rows of bunks, a small stove at one end. The guards were alert but not brutal. The food in the mess hall, when it came that evening, was simple but hearty—beans, cornbread, some sort of meat stew. Coffee that tasted like it had been boiled in old boots, but hot.

The Geneva Conventions, Keller realized, were more than lines on paper here.

Lights-out came with the boring inevitability of camp life.

Yet he could not sleep.

He lay on his cot, listening to the night sounds—crickets, a distant dog barking, the faint clank of a rifle butt against a watchtower railing. Somewhere out in the dark, cattle lowed.

His mind ran the day on a loop.

Schmidt Ranch. Braun Dairy. Keller Feed Store. Albrecht Cattle Company.

He thought of textbooks back in Berlin that described America as a “mixed” nation—immigrants from everywhere, no real rootedness. A place of jazz and factories and skyscrapers, but not of deep tradition.

He thought of Nazi speeches that equated German identity with soil. Blut und Boden—blood and soil. The idea that being German meant being tied to a specific stretch of earth, one that justified expansion and conquest.

And now, in a Texas camp, he had seen German names not in ghettos or exile enclaves, but on mailboxes and shopfronts, treated as unremarkable. Flourishing.

He imagined a man named Schmidt standing on a porch in 1900, looking out over fields and deciding to stay. He imagined children learning English in school and Schiller at home.

He imagined a Germany that had left Germany.

The thought was treacherous.

He tried to push it away.

But under the creak of the barracks and the far-off yip of a coyote, the thought returned, whispering:

Perhaps the Reich did not own“German” the way it claimed.

Somewhere outside the wire, beyond the reach of any Reich decree, a man with Keller’s name lived on land he owned, under laws he’d chosen. A German who had become American without ceasing to be… something else.

Keller closed his eyes and saw again the rancher’s easy nod.

Respect? Coincidence? Fate?

He didn’t know.

He only knew that for the first time since the surrender, he was less afraid of captivity than he was of what this place might teach him.

Under a Texas sky painted with more stars than any North African night had ever shown him, General Reinhardt Keller stared into the dark and wondered, not for the last time, whether the most dangerous thing in Texas was not the barbed wire, but the truth waiting just beyond it.

Part 2 – The Germany Beyond the Wire

Texas dawn didn’t kick the doors in.

It seeped.

In North Africa, the sun had come up like artillery—sudden, violent, erasing shadows. In Texas, light rolled in slowly, a pale gold that washed over the fields and barracks like a tide, turning the mist over the low ground into thin strips of silver.

General Reinhardt Keller stepped out of the barracks when the guard barked for morning roll call.

The air felt… soft.

Not weak. There was a weight to it—a hint of heat waiting in the wings—but it did not have the desert’s cruel edge. He smelled damp earth, grass, cedar. Somewhere, cicadas buzzed, a strange metallic hum under the birdsong.

He squinted toward the horizon.

Beyond the barbed wire, pasture and fields rose gently toward a line of oaks. A church steeple poked above the trees in the distance. For a moment, if he blurred his eyes, he could imagine a village in Franconia—until a pickup truck rumbled down a dirt road, dust trailing behind it like a flag.

The Americans went through their count with habitual efficiency. Names mispronounced were corrected. A couple of men who’d tried to sleep in were dragged out, boots half-laced.

“Good morning, General,” one of the guards said in careful German as Keller passed.

“Guten Morgen,” Keller replied automatically.

The word fell oddly on his tongue here, like hearing a Christmas carol sung in July.

As the officers broke off toward their assigned work details, Keller noticed movement near the main gate.

A small group of farmers approached, each carrying crates. Their clothes were simple—denim trousers, faded shirts, broad hats. Dust clung to their boots. Their posture had the relaxed confidence of men used to their land and their labor.

They stopped at the gate, exchanged greetings with the guards. Keller expected at least a flicker of hostility, some sign that seeing German uniforms would rankle.

Instead, he heard the easy cadence of local English.

“Mornin’, Joe. Brought y’all those melons like we promised.”

“Appreciate it, Henry.”

“Might get some rain later if we’re lucky.”

Careless weather talk, the kind that only happened in places where the main concern was the sky and the soil, not artillery.

Then one of the farmers shifted his crate and, without looking directly at the prisoners, said something else.

“‘Morgen,” he called lightly. The word rolled out with a Texas drawl clinging to it, the G softened, the R rounded.

Still, Keller heard it.

German.

He wasn’t the only one.

Heads turned up and down the prisoner line as if someone had snapped a string.

The farmer—stocky, sun-dark, with creases at the corners of his eyes—grinned faintly, like a man tossing a stone into a pond, curious how far the ripples would go.

He introduced himself to a guard.

“Name’s Heinrich,” he said, then added with a shrug, “but ever’body calls me Henry.”

Heinrich.

In Keller’s mind, the name belonged to men in wool coats, to villagers leaning on shovels while discussing harvest rotations, to old uncles who carved toys for children at Christmas.

Hearing it here, wrapped in Texas dust, scrambled something in him.

“Did you hear that?” Vogle muttered beside him, voice low. “He’s—”

“I heard,” Keller said.

He watched the farmers follow a guard inside the gate. They moved with no caution around the barbed wire, no instinctive flinch at sentries with rifles. For them, the camp was a job, not a fate.

As they walked past the assembled Germans, one of the younger officers, a captain who’d grown up in the Ruhr, heard a fragment of conversation and let out a disbelieving laugh.

“They’re speaking Hessian,” he whispered. “The dialect. Or something very close.”

The farmers’ English flowed easily. When they switched to German, the consonants turned softer, older, but recognizable. It was like hearing his grandmother’s voice played through a gramophone that had spent fifty years in someone else’s attic.

One farmer set down his crate of cabbage with a grunt and wiped his forehead.

“My Großmutter came from Hessen back in… hell, I don’t know, eighteen-something,” he told a guard who’d asked. “Still cusses us out in German when we track mud in her kitchen.”

The guard laughed.

“Bet that sounds scary,” he said.

Across the fence, men who had marched under swastika banners stared as if witnessing a ghost.

Vogle leaned closer to Keller.

“How can this be?” he whispered. “They are not… enclaves. Not refugees. They are… comfortable. They joke with the guards. They drive trucks. And they speak our language like it’s… normal.”

Keller didn’t answer.

Because he didn’t know.

He felt a strange hollowness open in his chest. It wasn’t loss exactly. Not yet. More like the moment in a battle when you realize the enemy you’ve been trained to disdain is not only competent, but in some ways better prepared.

He watched Henry heft a sack of onions, chatting casually with an American sergeant about fence repairs and a cow that had gotten stuck in a ditch.

Their ease with each other was the part that shook him most.

The Reich had lectured endlessly about fractures in American society: class, race, politics. A nation of enemies shoved into one uniform, ready to turn on each other at the first stress.

Yet here a German-named farmer and an American guard—whose own name, Keller noted distantly, was Rodriguez—stood shoulder to shoulder discussing weather and football teams like old friends.

If these men, with German names, German memories, German songs in their cupboards, had chosen to be Americans… what did that say about the story Keller had been told of inevitable German destiny?

The question tasted like sand and ash.

Work that day was simple: hauling gravel, repairing sections of fence, stacking lumber. Officer labor, arranged more to occupy time and maintain discipline than to wring actual productivity.

The guards kept their distance, confident that the men in neat uniforms and polished boots weren’t about to bolt for the horizon.

By noon, the Texas sun had burned off the mist and settled into a steady, heavy blaze. Sweat soaked through undershirts. Dust rose from shovels and hung in the air.

At one point, as Keller straightened from a wheelbarrow, a sound drifted from somewhere beyond the camp.

Music.

Faint at first, like the memory of a tune. An accordion, if his ear wasn’t betraying him—a reedy swell and fall, woven with a guitar or maybe a fiddle.

The melody was unmistakable.

He froze.

“What is it?” asked the man next to him, wiping his face with his sleeve.

“Listen,” Keller said.

They did.

The tune floated on the warm breeze, bright and cheerful. It had words, though no one was singing just then. Keller knew them anyway.

His grandmother had hummed that song every Advent, fingers dusted with flour as she shaped cookies on a tray. It was played at weddings in his village, on crackling radios at small-town fairs.

Now it was being played on a Texas farm.

The wheelbarrow handles bit into his palms. For a moment, he felt dizzy.

A guard noticed his pause.

“You all right, General?” the American asked. “You need water?”

Keller swallowed.

“I am fine,” he said. “It is… nothing.”

It wasn’t nothing.

It was a crack in the wall widening.

Vogle appeared at his elbow, looking pale under the sunburn.

“They are playing… our music,” he said quietly. “Do they even know what it is?”

Keller watched a hawk circle lazily over the distant fields.

“I think they know exactly,” he said. “They simply do not consider it… foreign.”

Vogle shook his head, as if trying to dislodge a thought.

“How can they take our songs, our names, and make them American?” he whispered. “What part of Germany do they not have?”

Keller thought of Berlin under blackout curtains, of Goebbels on the radio, of men raising right arms in unison, lips tight.

He looked at the farmhouse roofline beyond the wire.

“The war,” he said softly. “They do not have the war.”

Not the way he knew it. Not the way Europe did—bomb craters, hunger, fear of the knock on the door at midnight.

Here, German heritage had taken a fork in the road sometime in the last century and ended up on a porch in Texas, playing an accordion for children chasing fireflies.

The realization made his throat ache.

The farmers came back the next day.

By mid-morning, a small wagon rattled up to the gate, pulled by an old tractor that coughed and sputtered but refused to die. Henry hopped down, wiping his hands on his trousers. Another man—taller, with a shock of gray hair and a grin that arrived a half-second before his words—followed.

They traded greetings with the guards, then rolled into the yard with their supplies.

Newspapers—yesterday’s, already a little outdated by the time they reached this corner of the state. Sacks of flour. Crates of peaches, the fruit fuzzed and golden.

Keller and a few other officers were working near the perimeter. The guards, trusting their discipline, didn’t rush to shoo them away.

Henry noticed them and ambled closer, stopping a respectful distance from the fence.

“Hot one today,” he said, words stretched by the Hill Country drawl. “Y’all holdin’ up all right? Heat’s a different animal than the desert.”

His English was clear enough that even those with schoolboy lessons could follow. Then, as if on a whim, he added, in that rounded, older German:

“Zu heiß? Oder gewöhnt ihr euch daran?”

Too hot? Or are you getting used to it?

A couple of officers answered before they could stop themselves.

“It is… different,” one said stiffly. “We will survive.”

Henry smiled, not unkindly.

“Ja,” he said. “You will.”

He tilted his head.

“You from Bayern?” he asked another, picking up an accent.

The man blinked.

“Yes,” he said. “Lower Bavaria.”

“My Oma,” Henry replied, slipping back into German, “came from near Würzburg. Came over when she was a little girl. My family’s been in Texas since… eighteen-eighty-something. Long time. But at Christmas, she still makes Lebkuchen and yells at us in dialect when we are too loud.”

There was a soft murmur along the line.

He talked about a festival they’d had the previous night. How the town gathered in a hall lit by lanterns. How they played old waltzes and new tunes. How kids stomped their boots in time. How his grandmother had insisted on singing a hymn in German before eating.

“It’s just how she is,” he said, shrugging. “We got country songs, too. Banjo, fiddle, the whole thing. Mixes together fine.”

He said it like blending cultures was as natural as mixing flour and water.

For Keller, raised in a system that treated culture like a controlled substance, the casualness was dizzying.

“Do you ever wish your family had stayed in Germany?” Vogle asked suddenly.

The question came out more sharp than he’d intended.

Henry considered it.

“No,” he said honestly. “They left for a reason. Didn’t like how things were. Wanted land. Wanted freedom to make their own choices. They loved what they brought with ‘em—songs, recipes, church traditions—but they wanted to choose what to keep and what to leave.”

He tipped his hat back a fraction.

“Seems to have worked out,” he added. “Most days.”

There was no edge in his voice. No boast. Just a simple accounting of the truth.

Keller felt the answer land inside him with the weight of a verdict.

They had taken the best of Germany and left the rest.

He thought of men back home who had stayed and told themselves leaving was betrayal.

What if it had been preservation?

As the conversation eased, a guard motioned Henry back toward the wagon.

“Come on, Hank,” the guard said. “Commander’s waitin’ for your peaches before they melt.”

Henry chuckled and started away.

Halfway to the tractor, he turned back.

“My wife sent something,” he said. “Figured maybe y’all would want it.”

He walked over with a tin lunchbox, held it up for inspection, then offered it through the fence to the nearest guard.

Inside were slices of cake.

Not the dense, dry bricks K-rations sometimes called dessert. These were moist, with a browned crust and soft crumb, flecked with cinnamon. Thin curls of steam still rose from them.

Apple cake.

The smell hit Keller like a punch.

His grandmother had baked the same thing every October, filling the house with spice and comfort as the days grew short. He could see her hands in his mind—thin, capable, flour-dusted.

“‘Apfelkuchen,” Vogle whispered, nose twitching. “From… an American.”

“Texan,” Henry corrected, hearing him. Then he smiled. “And German, I guess, if you go back far enough.”

The guard broke off a piece of cake, examined it as if suspecting a trick, then took a bite.

His eyes widened.

“Damn,” he said. “That’s good.”

He hesitated only a moment before handing the box through the fence to the nearest prisoner.

“Share,” he said gruffly.

Hands reached, wary and eager at once.

Keller took a small piece.

The first bite made his throat tighten.

It wasn’t identical to his grandmother’s recipe—the flour was different, the apples, the oven. But the essence was there. Sweetness, spice, the faint crispness of sugar caramelized at the edges.

Why? Vogle’s question from earlier echoed in his head, now colored with new meaning.

“Why would an American give us something like that?” Vogle asked under his breath.

Because generosity wasn’t a weapon here, Keller thought. Because feeding people wasn’t a transaction, but a reflex.

He couldn’t say it aloud.

He chewed slowly, aware of hands waiting their turn, of eyes closing briefly as the memory of home mingled with the reality of captivity.

A small act.

A devastating one.

The idea that kindness could come from the other side of the fence, unforced, uncalculated, felt more dangerous to the mental fortifications he’d built than any interrogation.

He’d been taught that Americans were crude, greedy, driven by money and base appetites. That they were weak and disordered beneath a thin veneer of power.

Yet here was Henry, offering cake through a fence, not to atone for anything or to curry favor, but because his wife had baked too much and it seemed a shame to let it go to waste.

It wasn’t American propaganda that was cracking.

It was his.

Nights in Texas came down warm.

Even with the day’s heat bleeding off the earth, the air retained a softness unfamiliar to men used to European winters or desert temperature drops. The barracks windows were propped open to let what little breeze there was wander through.

Inside, the officers lay on their cots, the day’s dust still clinging to their hair.

Conversations were muted, less brittle.

“Those farmers,” someone said across the room, “they are like… cousins we never met.”

“Cousins who did not grow up with the Reich,” another replied. “Lucky bastards.”

Hartmann scoffed.

“Do not romanticize them,” he grumbled. “They have chosen the enemy. They fight against Germany.”

“Against Berlin,” a quieter voice said. “Not necessarily against… all of Germany.”

Keller listened.

He heard men who, weeks ago, would have parroted party slogans without a second thought now wrestling with complications.

The war was still there, sharp and real. They were still officers, still proud, still humiliated by defeat. But Texas had slipped under their skin, bringing with it questions they had never been permitted to ask.

When the murmurs died down, Keller slipped out into the yard.

A guard nodded at him from the tower. Keller nodded back.

Crickets sang. Somewhere in the distance, a dog barked twice, then fell silent.

From beyond the fence, across the fields, came the faint strains of music.

Not the accordion this time.

A fiddle, lilting and bright, weaving through the evening.

At first, the tune was foreign—a quick, twirling thing that made his foot tap despite himself.

Then the melody shifted.

Slowed.

Softened into something else.

A lullaby.

He recognized it by the second line.

His mother had sung it to him when the world was no bigger than the farmhouse and the lane outside. When the worst thing that could happen was scraping a knee or losing a toy in the hay.

Now, across an ocean and a war, someone sang the same words in German on a porch in Texas.

Keller leaned his forearms on the top strand of the wire and stared into the dark, throat thick.

Behind him, footsteps approached.

Vogle, hands in his pockets, eyes on the farmhouse lights.

“Do you hear that?” he whispered, as if speaking too loudly might break the spell.

“Yes,” Keller said.

“They do not whisper,” Vogle said after a moment. “They do not lower their voices. They do not look around before they speak German. They sing it into the open air.”

There was no envy in his tone now.

Just wonder.

Keller thought of the line he’d flung at him earlier, in a flash of bitter clarity.

There are two Germanies.

The one we came from.

And the one that grew here without us.

He hadn’t wanted to believe his own words when he’d said them.

Now, listening to a lullaby hang in the humid air without fear, he couldn’t escape them.

Which Germany would survive?

The one that had built camps and marches and speeches and destinies… or the one that baked apple cake and kept songs alive out of habit and affection rather than command?

He didn’t know.

He only knew that, for the first time since donning a uniform, the idea that his homeland’s future might be shaped by people who had left it didn’t feel like betrayal.

It felt like a lifeline.

The lullaby ended.

Voices on the porch shifted to talk and laughter. A screen door creaked. A chair scraped. Normal life resumed.

Keller stayed by the fence a while longer, staring at the farmhouse glow until his eyes blurred.

Behind him, the camp lights hummed. Inside, the barracks smelled of dust and sweat and now, faintly, of cinnamon.

In his chest, something that had been rigid for years bent, just a little.

He didn’t know what would be left when the bending was done.

He only knew that Texas had shown him a Germany larger than the one he had fought for, and that knowledge would not fit back into the old borders no matter how hard he tried.

Part 3 – The Germany That Left

By the third morning, the camp had a nervous kind of energy—like men waiting for orders that hadn’t quite arrived.

The reason trickled through the barracks in fragments.

“The Kommandant went into town last night.”

“With the guards. To a festival. Some kind of… German-Texan thing.”

“He came back with flour on his boots.”

Keller listened without comment as he laced his boots. The idea of an American officer attending a festival hosted by men with names like Schmidt and Keller and Heidenmann felt almost absurd.

In his world, German gatherings had become arenas for speeches and symbols, every song weighed for ideological purity. The thought of people with German surnames inviting Americans to a celebration with no agenda beyond food and music made his brain itch.

Out in the yard, the air already had weight to it. The sky was a harsh, high blue, but the breeze that carried across the fields smelled faintly of something sweeter than dust.

Cinnamon.

As the prisoners fell in, a guard walked by carrying a cloth-wrapped bundle. He passed it to another, who unwrapped it briefly to check the contents.

The smell intensified.

Pecans and spice and sugar, wrapped in still-warm pastry.

A murmur ran down the ranks.

“Those from the festival,” one guard called toward the tower. “Leftovers. Henry’s wife can cook.”

Keller caught a glimpse as the guard re-wrapped the bundle.

Little spirals of dough, browned and glazed, tucked around chopped nuts.

His mouth flooded with memory.

His mother, hands dusted with flour, smiling as she tucked a tray into the oven before Sunday service. A plate on the table when he came in, still steaming.

He forced his eyes back to the horizon, jaw clenched.

Later, when work details were assigned, the guards seemed a shade more relaxed. One private hummed a tune under his breath that Keller recognized from nowhere in particular and everywhere at once—a simple dance rhythm, the kind people stomped to after harvest.

“What did they do there, at this festival?” Vogle asked a guard during a water break, unable to keep the curiosity out of his voice.

The guard shrugged.

“Same as always,” he said. “Ate too much. Fiddles, accordions, old folks singing in German, kids running around, some cowboy tried to teach your damned waltzes to a two-step and almost broke his ankle.”

He grinned.

“Good folks,” he added. “They wanted to make sure we were fed. Hell, they sent pastries for y’all too, if the captain signs off on it.”

Vogle blinked.

“Why?” he asked before he could stop himself.

The guard looked at him like the answer should have been obvious.

“Because that’s what neighbors do,” he said.

Neighbors.

The word sat strangely in Keller’s mind, applied to men outside a prison fence.

Henry came back that afternoon, just as the heat started to lean harder against the camp.

This time he had a small handcart instead of a tractor, its wooden sides piled with sacks and boxes.

He greeted the guards as if he’d seen them a hundred times, which he now had.

“Afternoon, boys,” he said. “Brought y’all some flour, sugar, a stack of newspapers. And peaches. Grandma says the peaches this year are almost as good as the ones from before the drought. She lies, but they’re pretty good.”

The commander came out to sign for the supplies, shirt sleeves rolled up, hat off. There was an ease between him and Henry that made them look more like men discussing barn repairs than officer and civilian dealing with enemy logistics.

When the paperwork was done, Henry drifted closer to the fence, as if pulled by curiosity and habit both.

Keller and Vogle, working a lumber detail nearby, found themselves wandering that way, too.

“Y’all hear the music last night?” Henry asked through the wire, eyes crinkling. “Town festival. First one we’ve had since my cousin got back from the Pacific. Figured it was time.”

“We heard,” Keller said. His voice came out rougher than he intended. “Your… grandmother. She sang?”

Henry laughed.

“Wouldn’t have it any other way,” he said. “She says if we don’t sing the old hymns at least once a year, Texas will forget where it came from.”

He shrugged.

“Then my nephew got out his guitar and ruined the mood with something about trucks and broken hearts, but that’s how it goes.”

The image—an eighty-year-old woman from Würzburg leading a hymn, followed by a lanky kid drawling about pickup trucks—was so ludicrous and so perfect that Keller almost smiled.

“These songs,” he said carefully, “they are… old ones.”

Henry nodded.

“Older than Texas,” he said. “Came over on the boat with my great-grandparents. Sometimes I think the only reason folks remember all the verses is because they had to sing ‘em to keep from going crazy on the ocean.”

His gaze drifted over the prisoners, lingering on faces that, to him, probably looked like a family reunion seen through the wrong end of a telescope.

“I imagine y’all know them too,” he said softly.

Keller swallowed.

“We did,” he said. “Some of us still do.”

He didn’t add: When it was still safe to sing them without someone counting how many were “German enough” and how many were suspect.

Vogle stepped closer.

“Do you ever wish,” he asked, “that your people had stayed? In Germany?”

Henry shifted his weight, considering.

“I reckon they didn’t,” he said finally, “or they wouldn’t have left.”

He hooked his thumbs in his pockets, looking up at the sky as if the answer might be written there.

“From what Oma says, life back home was pretty hard,” he went on. “Not just money. A lot of… rules. Who you could be, where you could live, what you could say about the men in charge. Her daddy got tired of it. Heard there was land over here. Heard you could keep your faith and your songs without having to salute some fool every morning to prove it.”

He looked back at them.

“So they packed up,” he said. “Brought what they loved. Left what they didn’t. Spent the rest of their lives trying to make sure their kids knew the difference.”

No hatred. No smugness.

Just a matter-of-fact description of a gamble that had paid off.

Keller felt the words slot into place inside him like the last pieces of a puzzle he’d been too afraid to finish.

He had been taught that the only true Germans were those who stayed and fought. That those who left were weak, traitors to blood and soil.

Now he stood in front of a man whose family had left half a century earlier and somehow managed to keep more of Germany’s soul intact than the state that claimed to embody it.

The realization hurt.

It also… relieved something.

If the best parts of his culture had not been extinguished by war and ideology, but had found new life in places like this, then perhaps the story of his people did not end in rubble and shame.

Perhaps it bent here, in directions the Reich could not control.

“Y’all look tired,” Henry said abruptly, as if sensing the shift and choosing mercy over further explanation. He picked up a small tin box from the cart.

“My wife made these,” he said. “Said your cook could use something to practice with.”

He handed it to the guard, who flipped the lid, checked the contents, then held it up to the fence.

Inside were more pastries. Cinnamon, pecan, sugar.

“Just don’t let ‘em spoil you,” Henry added with a half-smile. “Our boys are eating worse than that in France right now.”

The reminder that other German boys were facing American rifles far from Texas hung in the air like a shadow.

Keller took it for what it was: a statement, not an accusation.

“We know,” he said quietly.

Henry tipped his hat.

“War’ll be over one day,” he said. “Y’all’ll go home. Maybe one or two of you will come back here on purpose someday. My Oma says she wants to see someone from the old country she can yell at who deserves it.”

He grinned.

“Until then, we’ll keep the cakes warm.”

He turned and walked back to his wagon, the sun catching the dust on his shoulders.

That night, the barracks hummed with a different kind of tension.

Not the anxious, brittle energy of men awaiting movement orders.

The restless agitation of minds trying to fit new truths into old frameworks and finding the seams popping.

“There are two Germanies,” Vogle said again, pacing between the bunks. “One behind us, one… out there.”

He jerked his chin toward the dark beyond the walls.

“The one we came from talks about destiny and struggle and purity,” he went on. “It builds camps. It burns books. It demands. It devours.”

He stopped, fists clenched at his sides.

“The one we see here sings old hymns under the stars,” he said. “It bakes cake for its enemies. It fights, yes, but it does not… consume itself.”

Hartmann snorted from his cot.

“You sound like a philosopher,” he said. “Next you will say Texas is salvation.”

“I will say,” Vogle shot back, “that if we had spent less time shouting about destiny and more time listening to men like Henry, perhaps we would not be sleeping in someone else’s barracks.”

Someone laughed, quickly stifled.

Keller sat on his bunk, elbows on his knees, listening.

The words he’d been avoiding all day came to him, clear and unwelcome.

We chose the wrong Germany.

Not wrong in the sense of geography. Wrong in the sense of which version of their shared identity they had decided to serve.

One built on uniformity and force.

One built on endurance and adaptation.

He thought of the young men he’d commanded in Africa. Their competence. Their sacrifice. How many of them would never see this land, never realize that a wider version of their heritage existed beyond slogans and salutes.

The thought felt like grief.

He stood abruptly and stepped outside, needing air.

The guard in the tower nodded.

In the distance, the farmhouse porch lights glowed.

Voices drifted—low, easy conversation. A woman’s laugh. Someone clapped to punctuate a joke.

Then, from that small island of light, a sound rose.

Not accordion this time.

Voices.

A hymn.

Not thundered by a crowd coerced into unity, but sung by a handful of people whose harmonies had been practiced over dinner dishes and long car rides.

The words were old—a simple chorale about rest and grace. Keller had sung it as a boy in a church with stained glass that had probably shattered by now under Allied bombs.

He leaned against the fence and closed his eyes.

The text took on new weight here, carried not by a congregation watched by party officials, but by families on a porch, in a language they were under no obligation to remember.

Behind him, boots crunched in the gravel.

Vogle joined him, shoulder to shoulder, silent for a long moment.

“They are not afraid,” he said finally. “To sing. To be who they are. No neighbor will report them. No official will count their hymns for… ideological content.”

“No,” Keller agreed.

He let the hymn wash over him.

He thought of his oath.

He had sworn loyalty to the state. To the Führer. To a vision of Germany that demanded everything and forgave nothing.

He had kept that oath as best he could, through campaigns and retreats and now surrender.

But standing under a Texas sky, listening to a living, breathing version of his culture that had never needed fear to survive, he realized something that hurt more than capture ever had.

His oath had been to a narrower Germany than the one that actually existed.

A Germany that had mistaken control for strength.

That had believed identity was a fortress to be defended, not a bridge to be crossed.

When the hymn ended, the porch voices faded into murmurs again. Chairs scraped. A screen door sighed.

Keller stayed where he was, fingers curled in the fence.

“Which Germany will survive this war?” Vogle asked quietly.

Keller opened his eyes.

He looked at the guard tower, at the barracks, at the flag that snapped on the camp’s central pole.

He looked at the dark silhouette of Henry’s house against the horizon.

“The one behind us,” he said, “may limp on for a few more years. In ruins. In shame. As a warning.”

He drew a breath.

“The one out there,” he went on, “will be singing this hymn long after our uniforms crumble. In German, in English, in a mixture of both. Their children will grow up never knowing what it is to fear their neighbors for the words they speak at the dinner table.”

He swallowed.

“If any part of our homeland has a future worth wanting,” he said, “it may be the part that left.”

The admission felt like standing on a dock, unclenching fingers from a rope as the ship pulled away.

He didn’t know yet what he’d hold onto next.

But for the first time since marching into Poland, he allowed himself the thought that defeat might be more complicated than flags changing hands.

It might be, in some wounded way, a chance.

Behind him, the camp lights buzzed. Tomorrow would bring more gravel, more routine, more small acts of kindness that made no sense within his old worldview.

Eventually, ships would come again. Trains. Orders that sent these men back across the ocean to a country changed by ruin and occupation.

When that day came, Keller suspected the hardest part of going home would not be facing what they had lost, but recognizing what had survived without them.

He lingered one moment more, memorizing the scent of cedar and warm soil, the way the Texas night held sound.

Then he turned away from the fence and walked back toward the barracks.

Behind him, in a farmhouse lit by lamplight, an old woman from Würzburg scolded a grandchild for tracking mud in, in a dialect that had crossed an ocean and found new ground.

The song she had sung lingered in the air, invisible and persistent.

So did the realization it had carried across the wire:

Germany was larger than the Reich had ever allowed him to see.

And somewhere between the barbed wire and the porch light, under a sky full of unfamiliar stars, General Reinhardt Keller began, quietly and painfully, to let go of the wrong Germany and make space for the one that might yet endure.

THE END

News

BREAKING: Ilhan Omar and Family Face Loss of U.S. Citizenship and Possible Deportation. SEE FULL HERE 👇

In what political observers are already calling “the wildest Tuesday since that one time Congress tried to pass a bill…

American Soldiers Describe Terrifying Things in German Forests…And the terrifying sight made him cover his mouth in horror.

Part 1 – The Thing in the Tree Line Grafenwöhr Training Area, BavariaWinter 2024 Staff Sergeant Jake Morris liked Germany…

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

Part 1 – The Hole in the Line December 16, 1944Ardennes Forest, Belgium Private Joe Miller woke up thinking the…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

Part 1 – The Paper and the Promise March 17, 1943 Berlin – and an ocean away, Michigan The room…

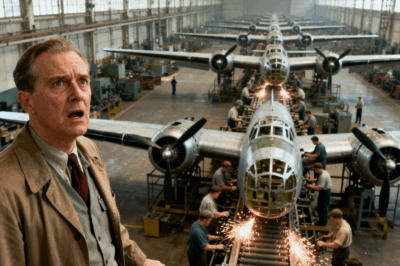

German General Couldn’t Believe the Allied Air Power Destroying His Panzers on D-Day

Part 1 – The Sky Above the Map June 7, 1944 Shortly after dawn Somewhere in southern England The coffee…

During Thanksgiving dinner, my five-year-old daughter suddenly shouted, ran to the table, and tossed the whole turkey onto the floor.

During Thanksgiving dinner, my five-year-old daughter suddenly shouted, ran to the table, and tossed the whole turkey onto the floor….

End of content

No more pages to load