Story title: The Gift Beyond the Wire

1. The Scar

December 24, 1943

Camp Hearne, Texas

The barbed wire sang in the cold wind.

It always did at night—a thin metallic whine as the gusts slid along the strands. After six months, Captain Hermann Burcher barely heard it anymore. It had become part of the background noise of his existence, like the murmur of men in bunk beds and the distant rumble of trains on the Santa Fe line.

Tonight, something pierced through it.

Children’s laughter.

American children’s laughter.

Hermann pressed his forehead against the rough inside boards of the barrack wall and peered through a knothole.

Beyond the double fence, on the dusty access road, cars and trucks were pulling up. Civilian vehicles. Women in coats. Men in Sunday hats. Kids bundled in scarves. Their arms were full—parcels wrapped in brown paper, baskets, wooden crates.

His abdomen twinged as he leaned forward.

The scar there—a pale, puckered line that ran diagonally from hip to navel—still hurt when he moved wrong. Four months earlier, shrapnel from a British mortar had torn through that flesh in the hills outside Bizerte. He’d felt the hot punch, the wet heat, the sudden looseness inside his own body.

By every law of war he understood, that should have been the end.

You get hit, you bleed out. Maybe your men drag you back to your own lines if they’re feeling lucky, or maybe you die in the dust with a final curse on your lips and a picture of home in your pocket.

He had not expected an enemy medic to drop to his knees beside him.

He had not expected the medic to be Jewish.

2. Africa – First Crack

May 7, 1943

Near Bizerte, Tunisia

“Hold him,” someone shouted.

Strong hands gripped his shoulders. The world tilted.

Pain pulsed from his belly in hot waves. He could smell cordite, sweat, the copper of his own blood.

American voices shouted in the distance. The rattle of light machine gun fire. The dull crump of a mortar.

Hermann blinked up at a sky too blue for dying under.

He was twenty-six. A captain in the Afrika Korps. Born in Hamburg, raised on Rosenberg’s race theories and the Führer’s speeches. His father had joined the Party in 1930 and never stopped talking about destiny.

By ten, Hermann wore the brown shirt of the Hitler Youth.

By fourteen, he could recite racial hierarchies the way other boys recited football scores.

By twenty, he marched into France convinced he carried civilization on his shoulders.

By twenty-three, he was in North Africa, wearing Rommel’s palm tree badge, certain that even in defeat, German honor would stand separate from the mongrel rabble of the Anglo-Saxons.

“Americans will fight without honor,” his instructors had said. “They have no discipline. They’ll torture prisoners. They’ll execute you in ditches. Better to die fighting than fall into their hands.”

He believed them.

Now American boots approached over the rocky ground.

He forced his eyes open.

An American helmet appeared in his field of vision. Then a face, young, sweaty, eyes quick.

The man’s hand pressed hard over Hermann’s wound.

“Shit,” the American muttered. Then, bluntly, in accented German: “Big hole, Fritz. But you’ll make it.”

Fritz.

The generic German name.

The medic’s hands moved automatically—field dressing, pressure, tourniquet. An IV needle slid into his arm with practiced ease.

Hermann’s mind spun.

This man had every ideological reason to let him die.

Jewish, he would learn later, from the name on a dog tag—Goldstein. A name that had been hissed in pamphlets and shouted in beer halls.

But his hands did not pause.

No interrogation.

No beating.

Just work.

Hermann passed out trying to understand why.

3. The Field Hospital – “Because You’re Human”

When he woke, canvas rippled above him.

The air smelled different. Less dust. More antiseptic. More… organization.

He was in a field hospital.

An American one.

He knew it before he saw the uniforms. The tent hummed with a brisk, efficient energy that had nothing to do with German improvisation and everything to do with American abundance.

A nurse moved between cots, checking dressings, adjusting IVs. Blond hair under a cap. Face drawn with fatigue, but hands steady.

She stopped at his bed.

“Morning,” she said in English. Then, realizing his confusion, switched to slow, careful German. “How do you feel?”

He looked down.

Bandages wrapped his abdomen.

He was alive.

They had operated on him.

The idea rattled around his skull like loose change.

He tried to sit up.

Pain stopped him halfway.

“Don’t,” the nurse said. Her hand on his shoulder wasn’t gentle, but it wasn’t rough either. “You had surgery. You move too much, you bleed.”

He swallowed.

Through the tent flap, he could see stretchers outside. Men in German feldgrau and American olive drab lay in rows waiting. Orderlies moved among them. The calls for “Next!” came in no particular national pattern.

He watched as a German private with a bubbling chest wound was rushed past.

Behind him, an American officer with a leg gone at the knee was pushed aside to wait.

Triage, he realized.

By need, not by nationality.

The nurse followed his gaze.

“We take the worst first,” she said. “Doesn’t matter what uniform.”

“Why?” he managed.

She frowned.

“What do you mean, why?”

He searched for words.

“I am… German,” he said. “Enemy. You… I…” His German failed him. His English was worse.

She looked at him for a long moment.

“Because you’re human,” she said finally. “What else would we do?”

He knew a thousand answers to that.

He had seen how SS units behaved in Poland. He had heard, and refused to dwell on, rumors from the East about what happened in camps whose names left a sour taste in his mouth even when he did not know the full extent of the horror.

“Because you’re human” had not been on the list.

Something hairline cracked in the foundation of his certainty.

Not a collapse.

Yet.

But a crack.

4. Crossing Over

The trip to America took three weeks.

Ship to New York. Train south and west.

His wound still hurt. He moved gingerly down gangplanks and across platforms, hand pressed to his abdomen more from habit than necessity now.

New York overwhelmed him.

Penn Station’s marble arches, the waterfall roar of voices, the announcements echoing over loudspeakers. America was noise and light and motion.

He’d been told it was chaos.

It looked like order, scaled up.

On the train, guards handed out sandwiches wrapped in wax paper, apples, coffee. The heat worked. The seats were padded.

Outside, America rolled by.

Farms that stretched to the horizon, rows of crops neat as parade grounds. No bomb craters. No burned-out shells of houses marking “terror bombing” like gravestones with chimneys.

Towns with churches and shops and people standing in front of them without fear of air raid sirens.

Factories with intact roofs and smoke rising from stacks in steady plumes.

Children in schoolyards.

It felt like an attack of plenty.

His father had told him, over dark beer at the kitchen table, that America was decadent, rotting, collapsing under the weight of its own mongrel mix.

The view outside the window called that a lie.

In North Africa, German units had fought on captured British rations, supply lines strangled by Allied naval dominance.

Here, guards finished half a sandwich and tossed the rest into a trash bin.

One of them caught Hermann watching.

“Want one?” the guard asked, holding up the other half of a ham and cheese.

Hermann’s throat tightened.

He took it.

He ate.

He didn’t say thank you.

He didn’t know how.

5. Camp Hearne – Rights

Camp Hearne looked like he’d imagined an American camp would—rows of white barracks, guard towers at the corners, barbed wire.

The Texas heat in June felt like someone putting a damp towel over your face.

They moved through intake in orderly lines.

Name. Rank. Unit. Location of capture.

It was clinical.

Measured.

A German-speaking American officer read out sections of the Geneva Convention in Hermann’s own language.

“You have the right to adequate food, shelter, and medical care,” the man said. “You have the right to refuse dangerous or humiliating work. You have the right to religious services. You may write home once a week. Letters are censored for military information but otherwise delivered.”

Rights.

The word sat oddly in his mouth.

He’d grown up hearing about duties.

The duty of the German to the Volk.

The duty of the soldier to the Führer.

Rights were something the Party talked about removing from enemies, not extending to them.

He signed the papers in a daze.

The barracks had bunks, mattresses, wool blankets. Not comfortable, but far from deprivation.

Food came three times a day.

Pancakes and bacon in the morning sometimes. Stew. Bread. Coffee. Often more calories than he’d had on the line in Tunisia.

He ate.

Each bite tasted like betrayal and like relief.

The camp library staggered him.

Shelves of books in German, English, French.

Goethe.

Schiller.

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

He stared at a copy he would have had to hide at home.

“I’m reading it,” a major named Kreuzmann said, coming up beside him. “Banned in Germany. Here? They hand it to us.”

“Why?” Hermann whispered.

Kreuzmann gave a half-shrug.

“Maybe because they think we’re worth more educated than ignorant,” he said. “Or maybe because they just don’t care if we read Mann. Maybe that’s the difference.”

6. Dr. Goldstein

The wound in Hermann’s abdomen was in a constant state of almost-healed.

The stitches held.

The tissue knit.

Then something pulled, and pain flared again.

He went to the camp hospital every week for months.

It was clean.

Organized.

Bright.

American doctors in white coats moved between cots. Nurses checked pulses.

The man who examined his scar most often was named Goldstein.

He was calm, meticulous, hands warm against persisting tenderness.

“Coming along,” Goldstein would say in German tinged with Yiddish. “Scar tissue looks good. Another few months, you’ll forget it’s there. Unless you twist wrong in cold weather. Then you’ll remember.”

One day in October, the question that had been burning in Hermann finally forced its way out.

“Why did you save me?” he blurted, as Goldstein straightened up.

The doctor glanced at him.

“You were wounded,” he said. “That’s what we do.”

“I’m German,” Hermann insisted. “We—” he swallowed—“our government… your people…”

Goldstein’s gaze sharpened.

“I know what your government has done,” he said quietly. “I read the same rumors you’ve heard. More, maybe. But I’m a doctor first. You come through that door, you are a patient. That’s it.”

He hesitated.

“And,” he added, “you personally didn’t design the Reich. You didn’t sign the decrees. We’re responsible for what we do. Not for every act of a government. Or at least, that’s how I choose to see it. Otherwise I’d never get out of bed in the morning.”

Individual responsibility.

Separated from national guilt.

It was a way of thinking that Nazi ideology had tried hard to erase.

In Hermann’s Germany, you and the Volk were the same. The state was the body; individuals were cells. To separate yourself from it was death.

Here, a man whose extended family might be dying because of Hermann’s army treated him, literally, as an individual body that deserved care.

Another crack, deeper this time.

7. Cornbread and Maple Syrup

Hermann volunteered for farm work.

Partly for the small wage—camp script you could trade in for cigarettes or writing paper.

Partly for the chance to see something beyond barbed wire.

He ended up at the Henderson farm.

Three hundred acres of cotton and corn. An old house with a wraparound porch and a kitchen that smelled of frying fat and coffee.

Mr. Henderson was wiry and stooped, with hands like tree roots. His eldest son was in Italy with the 36th Division. His youngest still at home, too young to be drafted. His daughter’s husband had died at Guadalcanal.

Mrs. Henderson fed the German work detachment lunch every day.

At her table.

On real plates.

“Ice tea?” she asked the first day, holding up a pitcher that glistened with condensation.

Hermann had never seen tea served cold.

He nodded.

The drink was sweet and strange, but good.

“You boys got family back home?” she asked, piling cornbread on plates.

“Yes,” Hermann said, cautious. “My mother. My father. Hamburg.”

“My boy’s in Italy,” she said. “Maybe you saw him shootin’ at you.”

She smiled wryly.

“I know you’re the enemy,” she went on, “but you didn’t start this war. Just got caught in it. Same as mine.”

Just got caught in it.

Not instruments of destiny. Not racial exemplars.

Just… people.

The simplicity was revolutionary.

8. Christmas

On Christmas Eve, 1943, the wind was sharper than usual.

Hermann wrote a letter to his mother at the small table in the barracks common room, choosing phrases that would pass censorship.

He did not write about Dr. Goldstein.

He did not write about the Hendersons’ kitchen.

He did not write about reading Thomas Mann in a Texas library.

He wrote about health.

About work.

About missing home.

Kreuzmann burst through the door.

“You have to see this,” he said, breathless. “At the wire.”

They went out.

Prisoners were gathering along the fence, faces pressed between strands.

On the road beyond, cars and pickup trucks were parked in a line.

Civilians climbed out.

Men in work shirts.

Women in dresses with coats over them.

Children in hats and mittens.

They carried baskets and boxes.

The camp commander stood with a group of guards at the gate. After a brief conversation, he did something unheard-of.

He ordered the inner gate opened.

Under the watchful eye of MPs, the civilians walked in, between barracks.

One older woman reached the nearest group of prisoners first.

She held out a bundle of knitted socks.

“Für Sie,” she said in careful German. “Merry Christmas.”

A boy, maybe eight, carried a basket of apples.

“These are from our tree!” he announced proudly. “Merry Christmas!”

One by one, they approached the men along the wire.

Cookies wrapped in wax paper.

Cigarettes in cartons.

Bars of soap.

Writing paper and pencils.

Carved wooden toys.

Socks.

Scarves.

Small things.

Everyday things.

Priceless things, in that place.

Hermann stood rooted as a little girl with braids marched up to him, holding a small parcel wrapped in red paper.

“This is for you,” she said solemnly.

His hands shook as he took it.

“Thank you,” he managed, the English words thick on his tongue.

“You’re welcome,” she said, and ran back to her mother.

He unwrapped it.

Inside: a pair of thick wool socks, a bar of chocolate, and a small wooden horse, roughly carved but clearly made with care.

Around him, hardened men who’d marched into Paris and shelled Tobruk held their own packages like relics. Some laughed, the sound too high. Some cried openly, no longer bothering to turn away.

Mrs. Henderson found him.

“Hermann,” she said. “I brought you something else.”

She handed over a worn book.

A Bible.

In German.

“This was my grandmother’s,” she said. “She came from Bavaria, 1882. Thought maybe it ought to find its way home eventually.”

“Your grandmother’s Bible?” he echoed, stunned. “To… me?”

“We’re all a long way from home,” she said. “She was once. You are now. So’s my boy in Italy.”

Her hand brushed his arm.

“War doesn’t last forever,” she added. “You’ll go home someday. When you do, I hope you remember there are good people all over, not just on your side.”

He couldn’t speak.

He just bowed his head.

That night, the camp chapel—converted mess hall, really—was fuller than usual for service.

The chaplain read from Luke.

“Peace on earth, goodwill toward men.”

Hermann had heard those words his whole life.

That night, they sounded less like something printed on Christmas cards and more like a description of what he’d just seen.

Goodwill.

Directed at him.

An enemy officer whose divisions had tried to kill their sons.

9. Aftermath – Scars and Lessons

The scar on his abdomen healed, leaving only a pale line.

The scar on his worldview stayed raw for years.

He read about the camps—Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor—in 1945 and 1946, sitting in the Hearne library with newspapers spread in front of him, seeing words like “gas chamber” and “mass grave” and “systematic extermination,” and felt sick.

“We didn’t know,” Kreuzmann whispered.

“We didn’t want to know,” Hermann replied. “That’s different.”

“What do we do with this?” Kreuzmann asked.

Hermann put his hand over his stomach, feeling the ridged line there.

“We remember,” he said. “We tell the truth. We spend the rest of our lives trying to be worthy of the mercy we’ve been shown.”

He returned to Hamburg in 1946 to a city that was, quite literally, half rubble.

His father was dead, killed in the final Soviet assault.

His mother had survived in a cellar with three other families.

“You’ve changed,” she said, touching his face.

“I’ve learned,” he answered.

There was a difference.

He became a teacher, then a writer.

He spoke in schools about Camp Hearne, about Dr. Goldstein, about Mrs. Henderson’s kitchen and the little girl with the wooden horse.

He wrote The Gift Beyond the Wire, a memoir that opened with the image of children pressing gifts through barbed strands.

“To the families of Hearne, Texas,” he dedicated it, “who taught a captured enemy soldier that humanity is not found in ideology but in acts of grace.”

In 1963, he went back.

Mrs. Henderson was old then, but alive.

He brought the Bible.

“I came to return this,” he said.

She pushed it back into his hands.

“Keep it,” she said. “It did what it was supposed to.”

“It did more,” he replied. “My body—Dr. Goldstein saved that. But you… your town… you saved something else.”

She shook her head.

“You chose,” she said. “We just opened the gate.”

10. The Pattern

Camp Hearne was one of more than six hundred prisoner-of-war camps in the United States during World War II.

Not all had Christmases like that.

Not all had Mrs. Hendersons.

But the pattern was similar.

Prisoners were fed adequately.

Treated under the Geneva Convention.

Allowed to read, to work, to learn.

Humane treatment was not a fluke.

It was policy.

Many went home unchanged.

Some did not.

Men like Hermann carried back not just the memory of full plates and working hospitals, but a lived experience that made the Reich’s propaganda ring hollow.

They became, in small ways, carriers of a different set of ideas.

That dignity did not have to be collective.

That enemies could choose not to become monsters.

That one could be proud of one’s country and still say, “We were wrong.”

The barbed wire at Hearne came down.

The barracks vanished.

The site became farmland, then a patch of scrub land with a small sign.

The real memorial sat in books on shelves, in conversations at tables, in the quiet decision of a former Afrika Korps officer to stand in front of students and say, “We believed lies. Let me tell you how I know.”

He died in 1998.

By then, his scar had long since stopped hurting when the weather turned.

He still traced it sometimes with his fingers, remembering the Jewish hands that had packed the wound, the Texas hands that had handed him a wrapped red parcel, the small hands that had pushed a carved horse through wire.

“The scar is my teacher,” he wrote near the end.

“It reminds me I was wrong. It reminds me I changed. It reminds me change is possible.”

On that cold Texas Christmas Eve in 1943, American families drove out to a camp full of men whose uniforms had marched through Europe and North Africa, whose government was murdering millions.

They brought socks.

Chocolate.

Toys.

Books.

They didn’t know if it would change anyone.

They didn’t do it as strategy.

They did it because it matched who they believed themselves to be.

It turned out to be a kind of strategy anyway.

Not for winning that war.

For helping shape how the next one might be avoided.

The barbed wire sang in the wind that night.

So did carols.

And somewhere in that uneasy harmony—a razor strand humming and a child’s voice saying “Merry Christmas” to a man who had been trained to hate her—something in Hermann’s understanding of the world broke.

Something else, harder to describe, began to grow in the crack.

The wire remains, in different forms, in different places.

We still stand on one side of it, taught to fear the faces on the other.

The question he left us with is simple:

When we walk up to that line, hands full,

do we bring weapons—

or gifts?

News

The Brutal Coincidence that Cost Germany 25,000 Soldiers

The Trap at Mons September 1944 Southern Belgium Two tides were flowing across the fields. One was ragged, gray, and…

The Tank American Crews Asked For – Why the M26 Pershing Missed WWII’s Big Battles

July 27, 1944 Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone….

(CH1) The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks | Wet Stowage Explained

July 27, 1944Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone. The…

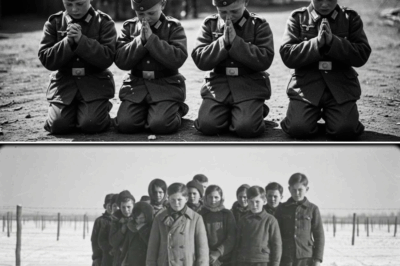

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Coca-Cola Instead

Story title: The Coca-Cola in the Snow The last days of the war tasted like dirt and metal. Thirteen-year-old Oskar…

Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

Story title: From Lies to Headlines 1. Surrender with a Satchel of Lies May 8, 1945 Southern Bavaria The last…

(CH1) Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway.

TOKYO — DECEMBER 8, 1941 The air in the Imperial Japanese Navy headquarters is thick with cigarette smoke and triumph….

End of content

No more pages to load