By seven in the morning, the world outside my Ohio window looked like it had been erased.

Snow had swallowed everything—the driveway, the front walk, the lawn, even the little stone border my late wife had been so proud of. A solid foot of heavy, wet white. At sixty-eight, with knees that sounded like popcorn when I climbed stairs, I was not in the mood to deal with it.

The doorbell rang.

On a freezing Saturday.

At 7:00 a.m.

“Who in the world…” I muttered, shoving my feet into slippers. My first thought was emergency. Second thought was some fool trying to sell me replacement windows. Either way, they were about to get an earful.

I opened the door.

The speech died in my throat.

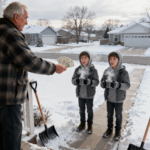

Two boys stood on my porch, half-buried in their own breath, which steamed in the bitter air. They looked twelve and fourteen, maybe. Skinny. Shivering. Their cheeks were bright red, their ears uncovered. One had on a hoodie under a jacket that looked about three sizes too small. The other wore a thin windbreaker that might as well have been paper.

Each of them held a snow shovel.

One of those shovels had its handle wrapped in duct tape from grip to blade, like it was being held together by hope and adhesive alone.

“Excuse me, Mr. Gable,” the older one said. I’d never seen him before in my life, but he knew my name. His voice tried to be confident and landed somewhere around determined. “Would you like us to shovel your driveway and walk?”

I glanced past them.

My driveway is long. The kind of long that feels fine when you’re thirty and a nightmare when you’re pushing seventy. It ran from the garage all the way down to the street, a pale, unbroken blanket that made my back ache just looking at it.

“How much?” I asked, mostly to see what they’d say.

They exchanged a look. The younger one shifted, boots squeaking in the packed snow.

“Twenty dollars,” the older boy said. “Total. For everything.”

I did the math in my head.

Three, four hours of hard physical labor in sub-freezing weather, split between two kids with one decent shovel and one held together with duct tape. Ten dollars each.

I could have said yes. Could have told myself they named their price, and found myself a bargain in the process. God knows I grew up in a time when you shut up and took whatever work came your way at whatever rate was offered.

But there was something in their faces that made me pause.

They weren’t hopeful.

They were desperate.

Desperation has a different light in the eyes. I saw it a thousand times in the factory—the guys who took double shifts when they shouldn’t because they were behind on the mortgage, the ones who volunteered for overtime even when they were limping because the car payment was due.

I recognized that look.

“You’ve got a deal,” I said. “But do it right.”

The relief that flashed across the older boy’s face wasn’t about getting out of the cold. It was like someone had just set down a weight he’d been trying to hold alone.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

They went to work.

From the living room window, I watched them for a while.

The older boy—he introduced himself as Marcus when I’d asked their names, his brother Leo—took the intact shovel and attacked the packed driveway like he had a personal grudge against it. Each scoop was full, thrown cleanly to the side, muscles straining under that thin jacket. The younger one followed behind him with the duct-taped disaster, scraping leftover snow, cleaning up the edges, doing the best he could with a tool that looked like it was one good scoop away from disintegrating.

No talking.

No phones.

No half-hearted motions.

Just two kids making those shovels earn their keep.

In my factory foreman days, I’d seen grown men with twice their size and four times their pay do half the work with twice the complaining.

After an hour, Leo’s legs finally gave out. He dropped onto my front steps, breathing hard, snowflakes clinging to his eyelashes. Marcus shoved his shovel into a snowbank and walked over to him.

They talked quietly. I couldn’t hear the words through the glass.

Then Marcus did something that twisted something in my chest.

He took the broken, duct-taped shovel and handed Leo the good one.

Leo shook his head like he didn’t want to, but Marcus insisted. The little one hesitated, then pushed himself back to his feet, gripping the better shovel with fingers gone pink from cold.

Marcus went back down the driveway with the taped mess on his shoulder.

I couldn’t watch anymore.

My knees complained, but I got up anyway. I went into the kitchen, grabbed the old saucepan, and heated milk on the stove. I still had cocoa mix in the cupboard—the good kind, not the cheap stuff. Forty years of marriage teaches you to always have something warm on hand for people who might need it.

I poured two big mugs, put on my boots and coat, and opened the front door.

“Union break,” I announced.

They both froze mid-shovel, eyes wide like I’d caught them doing something wrong.

“Come on,” I said, holding up the mugs. “You’ll work better if you can feel your fingers.”

They trudged up the driveway, snow caked on their boots, breaths ragged. Marcus took the mug gingerly, looking at it like it was some rare artifact. Leo wrapped his hands around his, shoulders trembling, then brought it up to his face, closing his eyes as the steam hit his cheeks.

“This is good,” he murmured, after a careful sip.

“It’s hot chocolate,” I said. “Made with milk. None of that water nonsense.”

A hint of a smile tugged at Leo’s mouth.

“That shovel won’t make it,” I said, nodding toward the one in Marcus’s hand.

He looked down at it like he hadn’t noticed the state of it until now.

“It’ll hold, sir,” he said quickly. “We’re almost done.”

“In my garage,” I said, jerking my thumb over my shoulder. “Back wall. Red handle. Heavy-duty steel shovel. For snow like this. Go get it. Finish with proper tools.”

He blinked. “We’re okay—”

“Son,” I said, leveling my gaze at him. “Your brother nearly broke his back trying to make that piece of trash work. Go get the shovel.”

There’s an art to giving orders kids will actually follow. You have to sound like you’re giving them instructions on wiring a panel, not offering help.

Marcus hesitated for half a heartbeat, then nodded.

“Yes, sir,” he said, and jogged to the garage.

When he came out carrying my industrial-grade shovel, his whole posture changed. He ran his hand along the steel edge like it was Excalibur.

“That thing’ll cut right down to the concrete,” I said. “You’ll be done in no time.”

The boys finished their hot chocolate, handed the empty mugs back with quiet thank-yous, and went back to work.

This time, the snow didn’t stand a chance.

By the time they knocked on my door again, three hours had passed.

I opened it to find them standing there, cheeks raw, hair damp with melted snow, coats spattered with stray flakes and slush. They looked like they’d been through a war and won.

“Finished, sir,” Marcus said.

I stepped outside to see.

They’d done more than finish.

The driveway was scraped clean, every inch of concrete visible, edges squared off like a plow had come through. The walkway was level, no packed snow waiting to turn to ice. The steps were bare. They’d even knocked the snow off the porch railing and brushed a neat path around my old Impala.

It was professional-grade work.

I’d seen less careful jobs from grown men paid by the city.

“You boys did a hell of a job,” I said. “Stay there.”

I went back inside, grabbed my wallet, and did some quick mental arithmetic. Three hours. Two boys. Twenty dollars an hour seemed fair; more than fair, but right.

I came back out with a folded stack of bills and held it out to Marcus.

He took it, automatically counting without even meaning to. His eyes went wide.

“Sir,” he stammered. “This is… this is $120. We said twenty.”

“I know what you said,” I replied. “You quoted a price. You delivered excellent service. I’m paying what it’s worth.”

“We… we only asked for twenty,” he said again, as if I hadn’t heard him the first time. Like the idea of being given more than the bare minimum was too foreign to accept.

“That’s the problem,” I said. “You’re selling yourselves short.”

He stared at the bills in his hands, Adam’s apple bobbing.

Next to him, Leo’s face, already bright red from the cold, crumpled. Quiet tears slipped down his cheeks, cutting fresh tracks through windburn.

“Hey now,” I said, softer. “It’s just money.”

“It’s not,” Marcus blurted. His voice cracked hard, like a tree branch under snow. “Sir, you don’t… you don’t understand.”

He swallowed, hard, like the words hurt coming out.

“Our mom’s a nurse,” he said. “At St. Jude’s. Night shift. She… she went out to go to work this morning and her car wouldn’t start. Battery’s dead. She was crying in the kitchen ‘cause she used all our savings on rent and… and… the auto parts store said a new battery is $114.”

He held the bills tighter.

“We were just trying to get anything,” he said. “We thought… if we shoveled enough driveways for twenty bucks, we’d get close.”

The breath left my lungs like someone had thrown a punch.

“These days” you hear a lot from people my age. Kids these days. Don’t want to work. Want everything handed to them. Lazy. Entitled.

But standing there on my cleared front step, I wasn’t looking at lazy or entitled.

I was looking at two kids who’d pulled on thin jackets, grabbed a broken shovel, and walked into a snowstorm before sunrise to try and buy their mother a car battery so she wouldn’t lose her job.

They hadn’t set up a GoFundMe. They hadn’t knocked on doors asking for charity. They hadn’t stood outside the grocery store with a cardboard sign.

They’d offered work.

Hard work.

For far less than it was worth.

“Looks like you’ve got enough for that battery,” I managed, my voice rougher than the wind. “And lunch money. Get the good stuff. No dollar menu.”

Leo let out a small sob and scrubbed at his face with the back of his glove. Marcus just nodded, jaw tight, eyes shining, clutching that money like it was the most precious thing he’d ever held.

“Thank you,” he said. “Thank you, sir. Thank you.”

“You earned it,” I said. “Now go on. That auto parts place on Main closes at noon on Saturdays.”

“You know about Monty’s?” Leo sniffled, surprised.

“Been buying parts from that old crook since ‘78,” I said. “Tell him Gable sent you. He’ll probably still overcharge you, but at least he’ll do it fast.”

That got a watery laugh out of both of them.

I watched them step off my porch and start down the street.

They didn’t walk.

They ran.

Bodies sore, fingers cold, faces raw, they sprinted through the snow toward the auto parts store three blocks away, toward a battery that would mean their mother could show up for work tonight and not be just another nurse marked absent.

After they were gone, I stood on my immaculate driveway for a long time, the cold seeping through my thick socks into my ankles, the sky still spitting flakes.

Inside, the house was quiet.

My coffee had gone cold on the kitchen table.

I thought about my own kids, long grown, scattered across states. About the men I’d supervised at the plant. About all the times I’d complained about “kids these days” while reading headlines and shaking my head at screens.

We teach children the value of money, we say.

Earn it. Save it. Don’t waste it.

What we don’t teach nearly enough is the value of their work.

That their time, their sweat, their effort has worth.

That they don’t have to undersell themselves to be worthy of respect. That charging less out of desperation doesn’t make their labor worth less.

Those boys asked for twenty dollars because that’s what they thought they could reasonably hope for, not because the labor was worth twenty dollars.

All they needed was one old man with bad knees and a decent pension to say, You’re worth more than that. Your effort is worth more than that.

People like to talk about what this country is built on. They argue and shout and wave flags and type furiously into little glowing rectangles about patriotism and hustle and who deserves what.

But what I saw that morning was simpler, quieter.

Two boys knocking on doors in a snowstorm with a duct-taped shovel, trying to hold their family together with their bare hands.

Work.

Integrity.

And the moment when someone finally saw them for what they were doing, not just what they were asking.

If you get the chance—and you will, if you pay attention—be that person.

The one who notices the duct tape on the shovel and the tremor in the voice. The one who understands that sometimes, the price someone names is not what their work is worth, but what their fear allows them to ask for.

Be the one who pays what it’s worth when you can.

Because in a cold, hard world, integrity really does pay.

Every single time.

The End.

News

Two Black twin girls were removed from a plane by the staff until their father, the CEO, was called to cancel the flight, causing…

On Friday afternoons, Newark International Airport always felt like a living organism—thousands of people pulsing through its veins, announcements echoing,…

“12-Year-Old Street Kid Warns Billionaire Not to Board His Plane—What Mechanics Found Seconds Later Shocked Everyone…”

“Don’t board the plane!” the boy shouted, voice cracking across the tarmac. Time seemed to slow. Cameras, crew, and journalists…

“NOW… Who Are You Talking To?” — Speaker Mike Johnson Just Dropped an Epstein Bombshell on Nancy Pelosi During a Heated Exchange, and Her Reaction Said It All 😳🔥 What Began as a Classic Congressional Back-and-Forth Took a Sudden, Dark Turn When Johnson Quietly Pulled Out a Document Linking a Known Epstein Associate to One of Nancy ’s Key Political Backers. The Chamber Fell Silent. Pelosi Tried to Pivot — But Johnson Cut In With Just Seven Words: “Now, who are you talking to?” Witnesses Say She Froze. Live Feeds Spiked. And Staffers Went Pale.👇 Full clip, document contents, and why insiders say this may be the moment that changes everything — in the comments.

“Why Speaker Johnson Says the Epstein Files Are the Real Capitol Crisis” Washington, D.C. — Tuesday’s press conference at the…

(CH1) “SORRY, NYC — I DON’T SING FOR CITIES THAT FORGOT WHO THEY ARE.” Dolly Parton Just Cancelled Every 2026 Show in New York… and Set Off a Culture War She Knew Was Coming. What Looked Like a Scheduling Change Turned Into a Full-Blown Statement Heard Across the Industry. No PR Filter. No Backpedaling. Just One Icon Taking a Stand Against What She Calls “Performing for Applause, Not Principles.” Within Hours, NYC Arts Figures Lashed Out — Calling Her ‘Outdated,’ ‘Divisive,’ and Worse. But Sources Close to Dolly Say She’s Ready to Burn the Whole Narrative Down — With One Message: ‘If truth sounds offensive, maybe that says more about you than me.’👇 What she really meant — and who’s panicking — in the comments.

Country music legend Dolly Parton has — in this fictional account — cancelled all of her 2026 New York City…

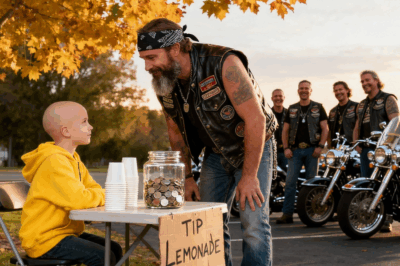

A young boy’s lemonade stand sat empty for hours… until a group of bikers noticed the real message hidden under his “50 cents” sign — and what happened next brought an entire neighborhood to tears.

The sun had just begun to rise above the rooftops when seven-year-old Tyler dragged his small wooden table to the…

End of content

No more pages to load