April 1945

Ten miles south of Munich

The war was coming apart at the seams.

You could smell it in the air—smoke and fresh-turned earth, oil and something bitter underneath. You could see it in the way German units moved now, not in tight, confident formations, but in scattered, exhausted threads, all running west.

On that particular morning, the war looked like a line of American trucks grinding to a halt on a dusty Bavarian road.

“Convoy, halt!”

Engines coughed into idling, metal ticking as heat bled into the spring air. A canopy of shattered trees threw broken shadows across everything—jeeps, trucks, helmets, eyes.

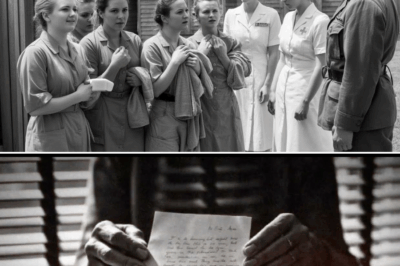

From the back of one of the trucks, they brought the women down.

Fifty-two of them.

Wehrmacht auxiliaries from a signals unit that had tried to outrun the front and failed. Uniform skirts mud-stained, boots worn thin, faces sharp from short rations and long marches. Hair tucked under caps that no longer sat straight. The eagle insignia on their sleeves looked tired.

Sergeant Harlon Brooks watched them climb down and line up.

He leaned against the hood of his jeep, helmet pushed back, a piece of gum working in his jaw. For three years he’d watched German soldiers appear out of forests and hedgerows with their hands up, faces young and old and everything in between. He’d seen the fear, the anger, the blank resignation.

He hadn’t seen many women in uniform.

They looked as beat as any infantry platoon he’d ever seen.

One of them caught his eye without meaning to.

She stood a little apart, not enough to be noticed by the officers, just enough that the gap was there. Posture straight because she was stubborn, not because she had the strength to spare. Auburn hair escaped in wisps from under her cap, catching the light. Dirt streaked her cheekbones. Her eyes, shadowed and tired, still held a spark that wasn’t quite defiance, but wasn’t surrender either.

A clerk, he guessed. The way her hands moved, the way she held herself. Not a combatant. Not by trade, anyway.

“Get ’em some water,” Captain Thorne called, voice brisk. “K-rations too. We’ll process ‘em at the field. Let’s move, people. This isn’t a sightseeing tour.”

Canteens started down the line. Brown waxed cardboard K-ration boxes followed, passed from big American hands to slender German ones.

As the group stepped off toward a clearing the engineers had turned into a temporary camp, the auburn-haired woman stumbled.

Her boot hit a loose stone. Her knee buckled.

Before Harlon thought about it, he’d pushed off the jeep and closed the distance. His hand clamped around her arm, steadying her before she went face-first into the dirt.

“Easy there,” he said automatically.

She tensed like she’d been hit. Her eyes flew to his—blue, he noticed, in that quick, too-long moment.

He realized she probably didn’t understand him and tried again, fumbling for the German he’d picked up from phrase books and half-translated interrogations.

“Langsam,” he said. “Ruhe. Du bist… sicher. Now.”

His accent was awful. Her mouth twitched like it might have been a smile in another life.

“Danke,” she murmured, voice hoarse.

He let go of her arm, fingers tingling.

Brooks, he reminded himself. You’re supposed to be watching, not catching. He stepped back, forcing his face into the blank, professional expression he wore for prisoners.

The women were herded—gently, but unmistakably—toward the field the Americans had fenced with barbed wire and tent poles. The “camp” was more rows of canvas than anything else, thrown up in a hurry under Captain Thorne’s barked orders.

“No rough stuff,” Thorne had told them earlier. “They’re prisoners, not targets. We treat ’em right, they behave, we all get through this in one piece. Got it?”

“Yes, sir,” the platoon had chorused.

Thorne was a New Yorker, Jewish, with a face carved into lines by too little sleep and too many operations orders. He’d come ashore on D-Day and fought his way across France and into Germany with the 45th Division. He had no illusions about the enemy.

He also had no patience for cruelty.

Harlon watched the women file into the wire, surprising himself by tracking auburn hair rather than insignia.

Get a grip, he told himself. She’s a prisoner. You’re a guard. That’s all.

And yet.

And yet.

Inside the perimeter, they parceled out blankets, tin cups, and space in the canvas tents.

The women moved in small clusters, instinctively gravitating toward those whose faces they knew. Some held themselves stiffly, eyes scanning for threats. Others sagged the moment they crossed into shade, fatigue finally winning.

The auburn-haired woman—Greta Voss, as Harlon would learn later—ended up in a tent with five others. She sat on the packed earth, back against a central pole, and turned the K-ration box over in her hands like she was afraid it might vanish if she opened it too quickly.

She peeled it apart carefully.

Crackers. A small tin of cheese. A triangle of chocolate.

She broke off the chocolate last.

It began to melt on her tongue.

Greta closed her eyes.

The last time she’d tasted chocolate, she’d been standing in line outside a bakery in Berlin, five years and a lifetime ago, watching snow fall on a queue of women all pretending they weren’t counting every ration mark. A man in a uniform had walked past, handing out Party leaflets about destiny and victory and sacrifice.

She wondered what he’d say now, if he could see this field.

The Americans moved among the tents, handing out canteens.

No shouts.

No leers.

Just “here you go” and “drink slow” and “there’s more where that came from.”

Their German was awkward, when they used it. Their hands were big and clumsy around the small tin cups. But the water was cool, and the way they turned their backs to give the women space felt like something foreign and fragile: respect.

Greta took the canteen offered at her tent flap, fingers trembling around the metal. When she looked up, the man holding it was the same one who’d caught her arm.

He smiled.

Not the thin, tight smile of someone doing a job they hated.

A lopsided, genuine grin that crinkled the skin at the corners of his eyes.

“Besser?” he tried. “Better?”

She nodded, stunned by the absurdity that an American sergeant with corn-yellow hair and Ohio in his vowels was worrying about her hydration.

“Ja,” she said. “Danke.”

“You’re welcome,” he replied.

The words came out oddly gentle.

He moved on, giving the next tent their share.

Greta cupped the canteen in both hands and took a small sip, then another, letting the coolness slide down her throat. It felt like the first honest kindness she’d received from anyone in months.

The propaganda posters—the ones that had screamed about American barbarians with dagger teeth and grabbing hands—went brittle around the edges in her memory.

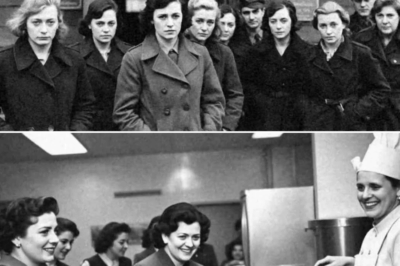

That evening, the mobile kitchen’s chimney puffed steam into the cooling air. The field smelled of coffee and stew.

Greta stood in line with the others, tin plate held out. A ladle thunked potato-and-canned-beef mixture onto it, followed by a heel of bread and half an apple.

It was more food in one portion than she’d had in three days.

She ate sitting cross-legged in the grass, spoon clanking softly against the plate. Each bite pushed warmth back into places that had forgotten how to feel it.

Beside her, Lena—the older woman with the deep lines around her eyes—ate in silence until tears started to spill onto her cheeks, cutting clean lines through the grime.

“I thought we would starve,” Lena whispered at last. “The stories…”

Greta nodded.

The stories had painted the Red Army as a nightmare, the Americans as only marginally better. They’d warned of looting, of assault, of camps where prisoners wasted away.

The leaflets dropped by American planes had promised fair treatment.

Each side had dismissed the other’s words as lies.

Here, in the simple arithmetic of stew and bread and blankets, the promises were outpacing the fear.

Across the field, the Americans sat on ammunition crates and folding stools, eating their own chow. Their laughter floated on the breeze—sudden bursts of it, surprised, relieved, exhausted. A young private from Texas pulled a harmonica from his pocket and coaxed a tune out of it, the plaintive notes threading through the rustle of tents.

Greta found herself standing near the wire as the sun slid down, sky going bruised-purple at the horizon.

She wasn’t the only one.

Dozens of women hovered there, drawn by the music, the light, the strange comfort of proximity to the men on the other side.

The sergeant appeared again, cup of coffee in hand.

He stopped a few paces away and, after a moment’s hesitation, stepped closer.

He held the cup out through the wire.

“Coffee?” he offered, searching for the word. “Kaffee?”

She took it.

Her fingers brushed his for a heartbeat.

“Thank you,” she said in English this time, surprising them both.

He blinked.

“You speak?” he asked, in his language now.

“A little,” she admitted. “School. Before.”

“Then this will be easier,” he said with a crooked smile. “I’m Harlon. Harlon Brooks.” He tapped his chest. “Sergeant.”

“Greta Voss,” she said. She pointed at herself, awkwardly mirroring his gesture. “Clerk.”

He nodded.

They watched the sunset together, steam curling from her cup.

“Beautiful night,” he said.

“Yes,” she replied. “Peaceful.”

They stood in silence after that, listening to the harmonica.

The war seemed farther away than it had in years.

The next morning dawned gray and threatening rain. Clouds stacked over the distant hills, heavy.

Processing began anyway.

“Voss, Greta,” the interpreter called.

Greta stepped forward.

Captain Thorne sat at a folding table, paperwork in front of him, pen poised. Behind him, Sergeant Mueller—German-American, fluent in both languages—translated with the weary precision of someone who’d been doing this for months.

“Name?” Thorne asked.

“Greta Voss,” she said.

“Rank, assignment, injuries,” Mueller translated.

“Auxiliary clerk, signals battalion,” she answered. “No wounds. Bruises from march.”

Thorne glanced at her, then at the file started by the patrol that had captured their convoy. He stamped something and jerked his chin toward another tent.

“Medical,” he said. “Next.”

The medical tent smelled of antiseptic and canvas.

Dr. Samuel Levy, his sleeves rolled up and stethoscope around his neck, moved briskly from woman to woman. He’d been a practicing physician in Chicago before volunteering. Son of German Jews who’d fled in the ‘30s, he carried his own reasons for being here.

“Open your mouth,” he said to one woman, checking gums. “Any fever? Dizzy spells? Cough?”

Mueller relayed the questions. Answers came back: no, yes, sometimes.

When Levy reached Greta, he checked her eyes, pressed gently on her abdomen, inspected the bruises blooming under her sleeves where a rifle butt had caught her during the chaos of capture.

“You’ve been through hell,” he said, almost to himself.

“Was ist das?” she asked quietly—what is that? The tone, she understood.

He met her gaze.

“Sie sind nicht tot,” he said in clumsy German. You’re not dead.

He handed her a small bottle of vitamins and scribbled something on the chart.

“Double rations today,” he told the orderly. “She looks like she could blow away in a strong wind.”

Greta stepped out of the tent feeling… unmoored.

American doctor. Jewish name. Professional, not punitive.

The equations she’d carried in her head for years—enemy equals danger, equals cruelty, equals inevitable humiliation—didn’t balance.

Harlon was waiting by the perimeter, ostensibly on patrol. His eyes flicked toward her, then away, then back, as if he were arguing with himself.

“Alles gut?” he ventured. All good?

She surprised herself by smiling.

“Yes,” she said. “All… gut.”

His grin lit like someone had switched on a lamp.

They walked along opposite sides of the wire, pacing each other.

“Where are you from?” he asked, fishing for vocabulary. “Stadt? Dorf?”

“Berlin,” she said. “You?”

“Ohio,” he replied. “Farm. Big field. Corn.” He mimed stalks growing tall with his hands. “Very boring. You would hate it.”

She laughed, a short, startled sound.

“After this,” she said, nodding toward the world, “boring sounds… nice.”

He sobered.

He understood that sentence in any language.

Rules hung over the camp like another layer of wire.

No fraternization. No unauthorized contact. No trading of goods or addresses. No friendships.

On paper.

In reality, war had rubbed the sharp edges off a lot of things.

Thorne’s orders were clear: maintain discipline, follow the Geneva Conventions, extract useful information without crossing lines. He knew his men were human. He also knew how fragile peace felt when you’d stepped over too many bodies to get to it.

If his guards slipped an extra pair of boots to a woman whose socks were more hole than wool, he pretended not to notice.

If a sergeant lingered a little too long along the fence during his patrol, speaking halting German to a woman with auburn hair, Thorne looked the other way—as long as it stayed on the right side of every line that mattered.

When the rain finally broke, it came in a wall.

Water turned the camp into mud in minutes. Tents sagged. Footpaths became slick trenches.

The quartermaster scrounged ponchos and spare boots from the supply trucks. Harlon ended up with an extra pair in his arms, his mind already made up.

He found Greta standing just inside her tent, watching the downpour with a resigned expression, bare toes already damp.

He thrust the boots toward her through the opening.

“For you,” he said. “Too much… Regen. Rain.”

She took them, fingertips brushing his.

“Danke,” she said. She looked up, meeting his eyes. “You… always give things?”

“Not always,” he said. “Just to people who fall on roads.”

Her smile, small and lopsided, did something to his chest.

The days settled into a rhythm.

Roll call. Breakfast. Work details for those who volunteered—kitchen duty, laundry, sorting supplies. Language classes in the afternoons, the Americans trying to teach democracy and English in equal measure. Evenings brought letters, harmonica tunes, and the soft murmur of voices around cook fires.

Greta found herself in the makeshift library often, fingers trailing over dog-eared paperbacks and Army-issue pamphlets. One thin volume with a faded cover caught her eye—a novel in English.

She checked it out, surprising herself.

Later, sitting near the wire with the book in her lap, she frowned at a sentence, lips moving silently as she tried to decode it.

“Need help?” Harlon’s voice came.

She looked up.

“You know this book?” she asked, holding it up.

He squinted at the title.

“Yeah,” he said. “Made us read it in school. ‘Of Mice and Men.’ Not… happy story.” He kneaded a knuckle into the air like he could knead the memory. “Good, though.”

“Too many words,” she grumbled, tapping the paragraph. “Too fast.”

“Here,” he said, dropping into a squat on his side of the wire. He pointed at a word. “This. ‘Dreams.’ You know?”

She nodded.

He said it slowly, letting her repeat it, gently correcting her vowels. They worked through the sentence together, his stubby pencil underlining parts, her accent thickening and thinning as she tried.

“Freedom,” he said, tapping another word. “Big one.”

She repeated it.

The sound felt heavy and strange in her mouth.

Later, in her tent, she whispered it into the dark.

Freedom.

The word had been weaponized in so many speeches. Here, in this muddy field behind American wire, it took on a new shape.

One evening, with thunder rumbling far off and the air heavy but cool, Harlon slid a small, folded scrap of paper through a gap in the fence.

Greta looked around automatically, then palmed it and slipped it into her pocket.

In the relative privacy of her tent, she unfolded it.

The handwriting was rough, blocky, in pencil that smudged if she wasn’t careful.

You make this easier.

– H.

Her heart thudded once, hard.

She pressed her fingers to the paper, then folded it back up and tucked it into the seam of her blanket.

No one had written her anything like that in years.

They were moved again before the month was out.

The war was ending in fits and starts, whole cities capitulating as new pockets of resistance flared. The Americans had more prisoners than they knew what to do with, camps swelling with numbers.

Greta’s group was loaded back onto trucks, this time with more organization, less chaos. The road took them north, past villages with roofs blown off, fields turning green despite everything.

A sign by the road read NÜRNBERG in battered letters.

The new camp sprawled across a hillside outside the city. Proper barracks lined the rows, not just tents. Washing stations. A medical hut with actual beds. Volleyball nets stretched between two poles, an incongruous touch of peacetime in the middle of barbed wire.

Greta scanned the convoy as they rolled through the gate.

She felt her shoulders loosen when she saw Harlon’s familiar profile in one of the escort trucks.

He found her later, of course.

On purpose.

They sat opposite each other at one of the long tables set up just inside and outside the wire, an English lesson disguised as security check.

He taught her “porch,” “cornfield,” “yard.”

She taught him “Straße,” “Himmel,” “Hoffnung.”

“Hope,” he said, pointing at the last one. “We can use more of that.”

“Had none,” she said plainly. “Before. Now… maybe little.”

He reached through the fence.

His fingers curled around hers.

It was a small contact, easily broken.

He didn’t.

“Greta,” he said quietly. “Ich… I…”

He groped for the words, in both languages.

“I can’t stop thinking about you,” he blurted out in English.

She understood enough.

Her cheeks warmed.

“Nor can I,” she said slowly.

They sat there, fingers laced through rusty wire, the war outside shrinking to the space between their hands.

The rules were still there.

They simply didn’t feel as important as this moment.

By June, the camp had a schedule posted on a board: English classes, civics discussions, movie nights with old reels of Hollywood films projected on a sheet hung against a wall.

Greta devoured it all.

She learned how American elections were supposed to work, how their Constitution divided power. She watched a black-and-white film where the good guys won without anyone saluting anyone else.

She and Harlon laughed under their breath when the hero kissed the heroine in grainy close-up.

Their first kiss was much less cinematic.

It happened by a stream.

The guards had begun allowing supervised walks to a nearby creek for laundry and washing. The women waded in, skirts hitched, laughing at the shock of the cold water.

Harlon was on p atrol detail that day, walking the perimeter of the little excursion with his rifle slung, boots sinking into the soft ground.

Greta moved toward a cluster of trees where the current slowed, ostensibly to rinse a shirt.

He followed, stopping at the shallows’ edge, pressed by duty and something else.

The inspector Officer Thorne’s distant silhouette turned for the tenth time, eyes scanning the larger group, making sure nothing obvious was happening.

Harlon stepped closer to Greta, the thin line of the creek between them.

“I don’t know how this works,” he said, words low, almost lost under the gurgle of water. “Any of it. The rules. After. But… when this is over, I want to see you. Not as a guard. Not as a prisoner. As… as a man. And a woman.”

Her heart climbed into her throat.

“In Berlin?” she asked. “Or your… cornfield?”

He huffed a laugh.

“Both,” he said. “If you’ll have me in either.”

She reached out, fingertips skimming the surface of the water, then rising to his.

Her hand was small in his, calluses and all.

“Yes,” she said simply.

The kiss that followed was tentative and quick, damp and slightly awkward with the creek between them and the possibility of discovery snapping at their heels.

It was also the sweetest thing either of them had known in years.

The war officially ended.

The camps began to empty.

Women were released first, sent back to shattered cities to rebuild lives that had been bombed to rubble. Men stayed longer, some for labor, some for trials.

Greta’s release papers came stamped with approvals and conditions. She was to report to a displaced persons’ hostel in Munich, check in with authorities, stay away from any political activity.

She clutched the folder like a lifeline.

“I will find you,” Harlon said at the gate, his hands wrapped around hers through the last segment of wire. “Munich is big. But not as big as the promise I made.”

“You better,” she replied. “I do not learn all your stupid slang for nothing.”

He laughed, eyes bright and wet.

“Hot dog,” he said.

“Swell,” she answered.

“I love you,” he added, in English.

She took a breath.

“I love you,” she echoed, the words foreign and familiar at once.

They let go when the guard cleared his throat politely.

Greta stepped onto the truck.

She didn’t look back until they were moving, and when she did, she saw him standing there—tall and solid, hand lifted in a salute that wasn’t quite regulation.

She raised her own hand in answer.

The road rolled out ahead.

The future was a tangle of visas and approvals and family conversations that would be hard on both sides of the ocean.

But it existed.

That was more than she’d had the year before.

They married in 1946.

The ceremony was simple: a small church in a German town that still smelled faintly of smoke, pews filled with a strange mix of American uniforms and German dresses, a borrowed white gown that hung a bit loose on Greta’s still-recovering frame, a ring bought with months of Harlon’s pay.

The pastor said the vows in German first, then English.

“I take you as my wife,” Harlon said, voice rough, “to have and to hold, to love and to cherish, from this day forward.”

“I take you as my husband,” Greta replied, the words clear, sure. “In Krieg und Frieden—in war and peace.”

They sailed to America on a ship crowded with war brides and soldiers, the Atlantic heaving under steel and hope.

Ohio was green and flat and so quiet at night it made Greta’s ears ring after the constant noise of the city. Harlon’s parents watched her with polite caution that softened over time into something warmer.

She planted flowers by the porch. He taught her to drive a tractor. They argued over how much sugar should go in coffee and whether sauerkraut was an acceptable side dish at Thanksgiving.

They had three children.

They told them bedtime stories about how they met.

“Your mother fell at my feet,” Harlon would say with a wink.

“I tripped over a stone,” Greta would correct. “He just happened to be in the way.”

“Best placement of my life,” he’d reply.

On quiet evenings, sitting on that porch, they sometimes fell silent at the same time, each thinking of a dusty road in Bavaria, the taste of K-ration chocolate, the first time the word “enemy” had failed to fit.

“Funny world,” Harlon would say.

“Yes,” Greta would agree. “Stupid. Beautiful.”

They grew old.

They lost friends, gained grandchildren, watched the world cycle through new wars and new peace with the perspective of people who had seen the worst and chosen better.

When they finally passed—he first, she soon after, as if the wire between them refused to stretch too far—their children buried them side by side in a small cemetery, one stone shared, two flags carved discreetly at the bottom.

In April 1945, on a road south of Munich, it had been almost impossible to imagine that ending.

All Greta had seen then was smoke, defeat, and a stranger’s hand offered through chaos.

All Harlon had seen was an exhausted woman in a uniform he’d been taught to hate, stumbling on a stone.

He could have let her fall.

He didn’t.

History books would mark that month for other reasons—capitulations signed, bunkers cleared, regimes ending.

Somewhere between those headlines was a smaller story:

A sergeant who leaned over a jeep hood, saw a woman steadier than he ever expected, and thought, easy there—

And a clerk who took a tin of coffee through a wire, tasted something kinder than any leaflet had promised, and thought, maybe the stories were wrong.

The war had been good at building fences.

They’d been better at reaching through them.

THE END

News

Amidst the chaos, they set up a makeshift aid station in a church displaying a prominent red cross, treating wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict.

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

German “Comfort Girl” POWs Were Astonished When American Soldiers Respected Their Privacy

The Day the Monsters Had Rules Schroenhausen, Bavaria April 1945 The engines came first. Margaret Miller pressed her forehead to…

My husband left us for his mistress—and three years later, I met them again. It was unbelievable, but satisfying.

After 14 years of marriage, two children, and a life I thought was happy, everything collapsed in an instant. How…

The Dishwasher Girl Took Leftovers from the Restaurant — They Laughed, Until the Hidden Camera Revealed the Truth

Olivia slid the last dish from a large pile into the sanitizer and breathed a sigh of relief. She wiped…

German Women POWs in Oklahoma Were Told to Shower With Water — And Burst Into Tears

Story title: The Day the War Fell Off Their Skin Camp Gruber, Oklahoma April 1945 The truck came in on…

“Are There Left Overs?” Female German POWs Were ASTONISHED When They First Tasted Biscuits and Gravy

Story title: Biscuits and Mercy Camp Somewhere in the American Midwest Late 1944 The first thing they noticed was the…

End of content

No more pages to load