Story title: The Law Above Orders

1. The Last Case

Bavaria, May 7th, 1945

The coffee was what unnerved him.

Not the American soldiers in his farmhouse doorway, not the trucks in the lane, not even the knowledge that the war was over and that men in his position rarely survived the signing of surrender papers.

It was the coffee.

Real coffee.

Not the bitter grain mixture that had passed for it in Germany for three years, but the dark, oily brew he remembered from cafés in Heidelberg before the world had gone mad.

Colonel Richard Mayer sat at a rough wooden table in a requisitioned farmhouse south of Munich, porcelain cup trembling in his hand. Across from him, a young American lieutenant with a notebook sat relaxed, helmet on the floor beside his chair.

On the floor next to Mayer’s boots rested a leather briefcase.

Inside: 217 case files.

Each file contained the name of a Wehrmacht soldier, a charge, a verdict.

Undermining military morale.

Desertion.

Cowardice before the enemy.

Each file had ended the same way.

Guilty.

Death.

No appeal.

Richard had drafted each indictment himself, in tight, precise handwriting, the way a good jurist should. The law had been clear. The orders had been clear. The state had spoken.

Now the state lay in ruins, Berlin a broken tooth in Europe’s jaw, and a lieutenant from the victorious army was pouring him coffee as if they were colleagues about to discuss a trial instead of enemies at the end of one.

“Colonel Mayer,” the American said in careful German, “we need lawyers who understand Wehrmacht courts. You’re going to help us.”

Richard set the cup down.

“Help you with what?” he asked.

“Trials,” the lieutenant said. “Real ones. With evidence. Defense counsel. Procedures.” He slid a folder across the table.

On its cover, stamped in black ink, were the words International Military Tribunal.

Richard’s throat tightened.

Trials.

Not firing squads.

Trials with rules.

Rules that might judge the people who had written his own.

For the first time in twelve years, Richard Mayer’s legal instinct—the part of him that had gone dormant under orders and ideology—stirred.

2. Jurist of the Reich

In 1928, Richard Mayer had sat in a very different room—a lecture hall in Heidelberg University—arguing about Prussian military law.

His doctoral dissertation had been on the evolution of military justice from Frederick the Great to the present.

He believed in order.

In hierarchy.

In rules applied precisely.

Law, he liked to say, was architecture made of words.

When the National Socialists came to power in 1933, he was thirty-one, a bright attorney in Berlin with a stubborn streak of idealism about the German state. The new regime spoke of restoring order, discipline, greatness.

They needed military lawyers.

They offered him a post in the Wehrmacht legal service.

He accepted.

In 1934, his first case as a military prosecutor involved a private who had criticized Hitler’s leadership in a barracks conversation. The evidence: two statements from fellow soldiers.

There was no defense counsel.

No cross-examination.

Richard drafted the indictment in three hours.

The court-martial took forty minutes.

The sentence was death by firing squad at dawn.

Richard reviewed the paperwork afterward, checked that the paragraphs had been properly cited, that the execution had been recorded in the ledger.

Then he opened a new file.

And another.

And another.

The legal code he applied—the Military Penal Code of the Greater German Reich, revised 1938—had stripped away most of the protections that his professors in Heidelberg had taught him to revere.

Right to counsel? Removed.

Judicial independence? Subordinated to commanding officers.

Proportional punishment? Sacrificed to “the needs of the war.”

“Undermining morale,” “defeatism,” “cowardice”—all capitol offenses.

He memorized every clause.

He believed in them.

The Führer’s orders carried the force of law. The state defined justice. Individual conscience had no place in military discipline.

By 1943, he was a colonel in Berlin, overseeing three rooms of prosecutors and processing seventy cases a month. He didn’t attend the executions. He read the confirmations.

Death by hanging.

Death by firing squad.

Death, death, death.

His handwriting remained neat.

The ledgers were always up to date.

3. The Camp

The American prison camp near Augsburg held seven thousand Wehrmacht officers.

Richard arrived there on May 11th, 1945, briefcase in hand, expecting at any moment to be marched past the barbed wire into a quieter corner of the woods and shot.

Instead, guards took his photograph, recorded his rank and service history, issued him a bunk assignment in Barracks 43, and left him alone.

No interrogation.

No tribunal.

No sentence.

The camp ran with disconcerting efficiency. Three meals a day. Sick call. Mail that sometimes, miraculously, reached families in bombed-out cities. A lending library with books in German and English. Time in the yard for exercise.

He waited for the other shoe to drop.

It didn’t.

Then one evening in late May, as he sat on a bench in the recreation yard, watching other officers play cards in the weak sunlight, an American captain in khaki approached.

He was young—Richard guessed no more than twenty-eight—with wire-rimmed glasses and a folder under his arm.

“Colonel Mayer?” he asked in German.

“Yes,” Richard said warily.

The captain sat.

“My name is James Morrison,” he said. “U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps. I’d like to ask you some questions about Wehrmacht military courts.”

What followed wasn’t an interrogation.

It was something Richard hadn’t had in years.

It was a seminar.

“Do you believe,” Morrison asked one evening, “that orders constitute legal justification for any action?”

Richard answered without hesitation.

“Orders from legitimate authority carry legal force,” he said. “If a soldier disobeys lawful orders, he undermines discipline. The army collapses.”

Morrison nodded.

He reached into his folder and pulled out a document.

“Read this,” he said.

It was titled Charter of the International Military Tribunal.

Richard skimmed.

Then stopped.

Article 8:

“The fact that the defendant acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior shall not free him from responsibility…”

He read it again.

And again.

It was a knife in the foundation of everything he’d practiced.

Above orders.

Above the state.

Responsibility that did not vanish when a higher authority spoke.

“Who wrote this?” he asked.

“Representatives of the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union,” Morrison said. “In London. They intend to try your leaders under it.”

“Try,” Richard repeated. “Not simply… dispose.”

Morrison smiled without humor.

“We’re lawyers,” he said. “This is what we do.”

4. Education Behind Wire

The conversations became daily.

Morrison brought colleagues. They brought books. Case law. Philosophical texts.

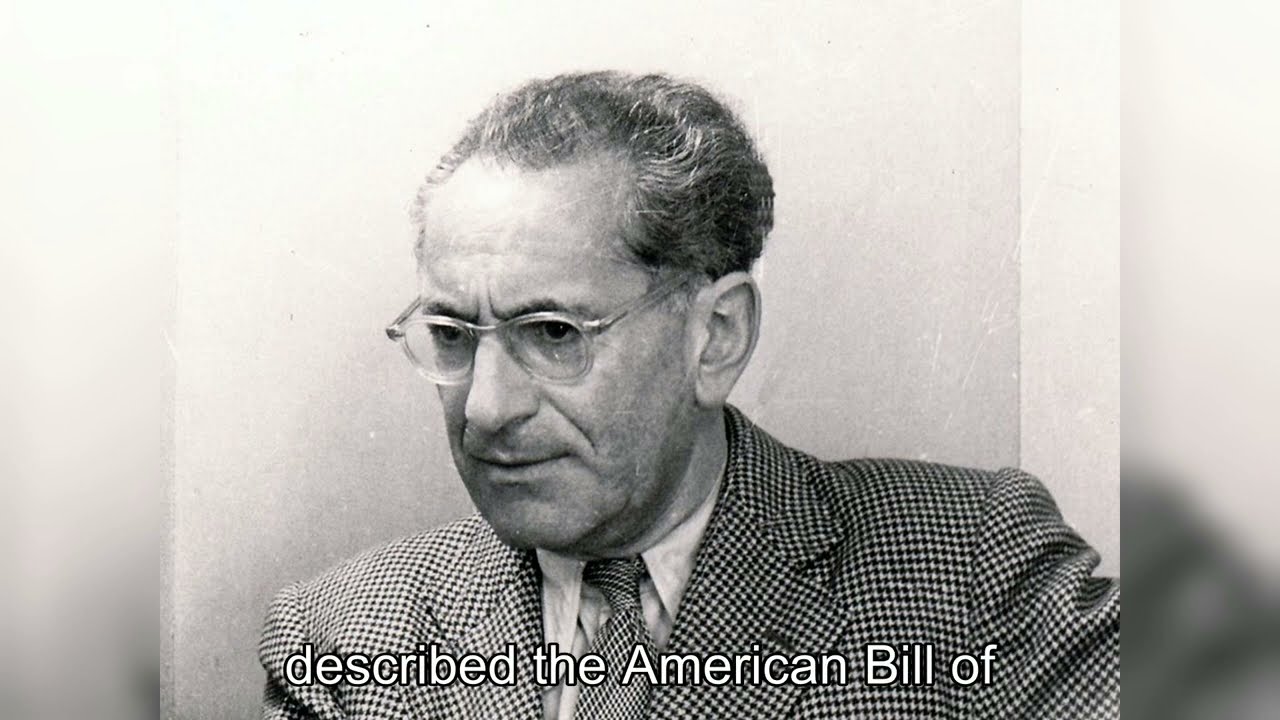

They gave him translations of the American Bill of Rights, explanations of habeas corpus—this idea that the state must justify detention to a court—that seemed almost fantastical to a man whose government had arrested and shot people with a stroke of a pen.

They described adversarial procedure. Witnesses cross-examined. Evidence challenged.

They showed him Supreme Court cases.

They talked about separation of powers, about the dangers of executive authority without judicial oversight.

He argued.

Of course, he argued.

“These concepts are naive,” he said. “Utopian. A state at war cannot function with such… constraints. Military necessity requires harshness.”

Morrison listened.

Then asked questions.

“You prosecuted soldiers for criticizing the regime,” he said. “Did you ever verify whether their criticisms were true?”

“It was irrelevant,” Richard said. “Their truth or falsity did not matter. Discipline mattered.”

“You denied defendants counsel,” Morrison went on. “Without an advocate challenging your evidence, how did you ensure factual accuracy?”

Richard faltered.

“We had investigators,” he said. “Reports. Affidavits.”

“Signed under what conditions?” Morrison asked. “With what pressures? With what standards of proof?”

Richard realized, uncomfortably, that he had never dug deeply into those questions. His role had been mechanical: apply the statute, draft the indictment, move to the next file.

“You sat on courts where commanding officers could overturn acquittals,” Morrison said one afternoon. “But not convictions. How is that different, functionally, from letting a mob lynch someone acquitted in a courtroom?”

Richard had no answer.

Those questions, dropped like pebbles, accumulated into weight.

He went back to his barracks and found, for the first time, that the neat edges of the law he had memorized did not align with the cracks appearing in his certainty.

5. Nuremberg

In June, Morrison arranged for him to attend preparatory sessions for the trials in Nuremberg.

In a makeshift classroom in the camp, American prosecutors spread out captured documents, charts, photographs.

They talked him through their cases.

He saw orders he’d heard rumors of—Kommissarbefehl, directives to execute Soviet political officers.

He saw memos, signed by men he’d briefed, authorizing “reprisal” shootings in occupied territories.

He saw detailed reports from Einsatzgruppen—graphing shootings of thousands—and the signatures at the bottom.

His own name appeared more than once.

On legal opinions.

Authorizing the execution of soldiers who had refused to carry out those reprisals.

He had charged them with cowardice, with undermining morale.

The Americans called it what it was: murder.

For the first hour, horror at the scale of the crimes froze him.

For the second, recognition of how military courts had been used to grease the machinery of those crimes made his stomach churn.

For the third, the personal realization sank in: he had not been a neutral technician.

He had been a necessary cog.

He had turned law into a weapon.

He had killed men on paper so that others could kill civilians in reality without resistance.

He left the classroom that day and vomited behind the barracks.

6. Unlearning

After that, he read.

Voraciously.

He requested American legal philosophy from the camp library: Federalist Papers. Commentaries on constitutional government. Cases on free speech, due process, judicial review.

He read Hugo Grotius on the laws of war. The Hague conventions. The 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs.

He read about “natural law,” about the notion that there were principles of justice that did not depend on the commands of any particular state.

He filled notebooks with cramped handwriting, trying to reconcile concepts that had never previously shared a page in his mind.

If law is only what the state says it is, he wrote once, then no action by the state can ever be unlawful. This eliminates any basis for judging state crimes. It transforms law into mere technique for the application of power.

In August, he received notice that he would be called as a witness in preliminary proceedings against senior Wehrmacht legal officers.

He would be asked if he believed he had committed crimes.

He lay awake that night, staring at the barracks ceiling, replaying every indictment he’d written.

The private executed for a joke about Hitler.

The sergeant executed for refusing to beat a Jewish family in Poland.

The lieutenant executed for not shooting prisoners after a partisan attack.

He had followed the law as written.

The law had been criminal.

Did that absolve him?

“This is the bureaucrat’s defense,” he wrote. I was only following orders. I was only following the law. It is no defense at all. It compounds guilt by cloaking it in procedure.

He knew, then, that when asked, he could not simply say, “I did my duty.”

The word “duty” had been damaged beyond use.

7. The Law Above Law

In September, he sat in the gallery of Courtroom 600 in Nuremberg.

He watched Göring, Ribbentrop, Keitel, and the others sit in the dock, headphones on, while prosecutors from four nations laid out the case against them.

He watched defense counsel rise—not to be shot for daring to represent enemies, but to cross-examine witnesses, to challenge evidence.

He watched judges deliberate.

He watched, stunned, as law was used not to defend a state, but to judge it.

The idea hit him with almost physical force.

Law could stand above governments.

Could apply standards that no Reichstag or Führer decree could override.

Could say, “This is crime,” even when it had been called “order.”

That night, back in his barracks, he wrote a seven-page letter to the tribunal administration.

He requested, when released, permission to study at a German university.

Not military law.

International law.

Human rights law.

He wanted, he wrote, to rebuild his juristic understanding from the foundation the regime had shattered.

He wanted to understand how Nuremberg was possible.

He wanted to help make sure it wasn’t a one-time anomaly.

8. Return

He was released from the POW camp in March 1947.

He was forty-nine.

Germany was four zones and a pile of rubble.

He went back to Munich with two suitcases and a cardboard box full of books.

He enrolled at Ludwig Maximilian University alongside students young enough to be his children.

He sat in lecture halls and listened to professors talk about constitutional safeguards, human dignity, separation of powers.

Sometimes they glanced at him when they mentioned “jurists of the Reich.”

He did not flinch.

His second doctorate, completed in 1949, bore the title:

The Perversion of Military Justice under the Third Reich: A Legal and Moral Analysis.

In it, he dissected the code he had once administered. He showed how procedural protections had been stripped away. How judges had been subordinated to commanders. How “law” had been turned into a mask for arbitrary violence.

He wrote, in its conclusion: “A lawyer who defends the state machine against human dignity becomes an accomplice to tyranny.”

The faculty read it.

Some with discomfort.

Some with relief.

For the first time, someone with hands blackened by the system was laying it bare from the inside.

They offered him a teaching position in Frankfurt.

9. Teaching and Making Amends

He walked into his first lecture in 1950, notes in hand, three hundred students staring.

He could see curiosity. Suspicion. A few expressions edged with hostility.

He put his notes aside.

“My name,” he said, “is Richard Mayer. I was a colonel in the Wehrmacht legal service. Between 1939 and 1945, I prosecuted 217 soldiers. Most of them were executed. I believed I was serving the law. I was wrong. Today, I am going to explain how that happened.”

He told them about his first case.

About his briefcase in Bavaria.

About Morrison’s questions.

About Nuremberg.

He explained what could have stopped men like him—and what had been removed deliberately to ensure nothing did.

Independent judges.

Defense counsel.

Appeals.

The ability of courts to say no to power.

He talked about “positive law” versus “natural law”—the idea that some rights exist by virtue of being human, not because a parliament says so.

He did not excuse.

He did not ask for sympathy.

He laid his sins on the table and then dissected the mechanisms that had made them possible.

His students left his lectures shaken.

Some in anger.

Some in gratitude.

All with a clearer sense that “following the law” was not a moral defense when the law itself was rotten.

He took cases, too.

He represented families of soldiers executed for “defeatism,” seeking to overturn their verdicts.

He helped Jewish survivors reclaim property seized under “racial laws,” arguing that such laws had never had legal validity.

He refused to represent former Nazi officials asking for leniency.

“I spent twelve years defending the state against its victims,” he told one. “I will spend what years I have left defending its victims against the state. You may find another lawyer.”

10. The Advocate

In 1955, he published Law and Conscience: The Duty of Attorneys under Dictatorship.

He examined lawyers in Nazi Germany, in Stalin’s Soviet Union, in other regimes where the state had claimed absolute authority.

He argued that legal professionalism required a higher loyalty—to human dignity, to justice—that could not be overridden by orders or statutes.

“When the law commands injustice,” he wrote, “it ceases to be law in any meaningful sense. The lawyer’s duty shifts from obedience to resistance.”

The book became required reading.

He testified before the Bundestag when West Germany debated reintroducing military courts in the mid-1950s.

He argued against capital punishment. Against allowing political offenses into military jurisdiction. For civilian oversight. For mandatory counsel. For appeals.

Most of his recommendations became law.

He attended the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem as an observer in 1961.

He listened to Eichmann claim he had “only followed orders.”

He heard his own past arguments echoed, stripped of their rationalizations and laid bare.

He went home and wrote an essay titled “The Bureaucrat’s Defense”, arguing that obedience did not neutralize guilt. It intensified it by demonstrating the willingness to put technique above morality.

In the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, he took the stand for the prosecution.

He explained how law had been used to make mass murder seem normal.

“I was one of those lawyers,” he said. “I dressed violence in legal language. I made it harder for good men to refuse evil orders. That is why we are here now.”

Some called his testimony courageous.

Some called it self-serving.

He didn’t care.

He wasn’t trying to save himself.

That ship had sailed in 1934.

He was trying to ensure that the students in the back of the courtroom, the ones who would draft the next generation’s laws, understood what had happened when their predecessors had failed.

11. The Last Lesson

He retired from practice in 1968 at seventy.

He kept teaching.

His last lecture, three months before his death in 1975, took place in a packed hall in Frankfurt.

He stood at the podium, thinner, hair white, eyes still sharp behind glasses.

“I practiced law for twelve years under a criminal regime,” he began, without preamble. “I told myself I was following the law. I told myself I had no choice. Both were lies.”

He paused, letting the words sink in.

“The law I followed commanded murder,” he continued. “I had choices. I chose comfort over courage. I chose career over conscience.”

He looked out at the sea of young faces.

“Many of you,” he said, “will not be asked to defend mass murder. You will be asked to bend rules. To ignore small injustices. To draft opinions that make it easier for your clients, or your government, to do harm. Those choices will feel minor. They will not be.

“In those moments, remember: law is not whatever the powerful declare. Law is humanity’s attempt to replace force with justice. If you use your skill to help force masquerade as justice, you betray your profession—and yourself. I know this. I lived it. Learn from my failures. Do not repeat them.”

When he finished, there was a moment of silence.

Then the students rose.

The applause lasted longer than he expected.

He wept at the podium, not because he thought he’d redeemed himself, but because he knew they’d heard him.

He hadn’t earned forgiveness.

He had, at least, earned their attention.

Richard Mayer died later that year, aged seventy-seven.

His obituaries called him many things.

Wehrmacht prosecutor.

Human rights advocate.

Cautionary tale.

His name appears now in legal ethics textbooks, alongside case citations and quotes from his memoir From Reich Prosecutor to Human Rights Defender.

Some see in his life an argument for transformation—that even those deeply complicit in evil can change.

Others see a warning that no amount of later good works can erase the harm done when law is turned into a weapon.

Both are true.

He is remembered, ambivalently, as both.

The man who killed 217 soldiers with his pen.

And the man who helped write the constitutional protections meant to keep their grandchildren safe from a state like the one he once served.

In that tension, in that refusal to let his story resolve into something tidy, lies the point.

Lawyers are not immune to evil because they know the codes.

They are dangerous precisely because they can cloak evil in legality.

What they choose to do with that power—whom they serve, what standards they hold themselves to—matters.

Richard Mayer’s life is proof, simultaneously, of how wrong those choices can go—

And how far it is still possible to come back.

News

Black Maid Stole the Billionaire’s Money to save his dying daughter, —what he did shocked everyone

By the time the handcuffs clicked shut around her wrists, Clara Briggs had stopped feeling like a person. The metal…

Millionaire Secretly Followed Black Nanny Home After He Fired Her – What He Saw Was Unbelievable

By the time Charles Whitmore realized he’d fired the only person holding his family together, he was sitting in his…

Racist In-law Pours Wine On Black Bride, Unaware Her Father Is A Millionaire

The first glass of wine hit her like an accusation. One splash, then another—thick, red, and deliberate. The music cut…

Millionaire Installed CCTV to catch Black Nanny, But What He Found Out Shock Him

Jack Thompson had spent his whole life building walls. Not the kind made of brick and stone—the kind made of…

A beggar was thrown out of the car dealership, not knowing he was the undercover owner!

Alex Mercer built his empire on control. Numbers, projections, margins—those were things he understood. Nothing in his dealerships happened by…

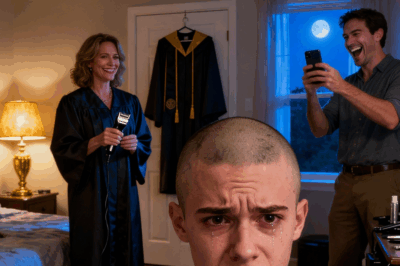

The night before my graduation — the day I worked four years to reach — my mom stormed into my room with clippers in her hand. With a cruel smile, she shaved my head bald, mocking me, “Bald like your future.” My dad stood beside her, laughing, snapping pictures as if it were the funniest family joke. But what they didn’t know was that this humiliation would not break me. It would become the fire that

The night before what should have been the proudest day of my life, I sat on my bed, carefully running…

End of content

No more pages to load