By the last year of the Pacific War, the world those women knew had shrunk to jungle, hunger, and orders shouted by voices that were no longer sure of themselves.

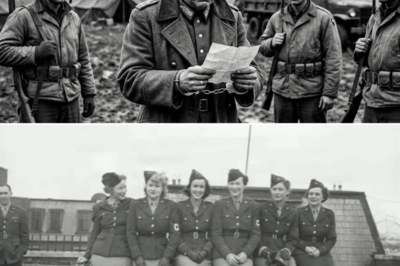

They were about two hundred in all, scattered near an abandoned Japanese outpost on a small island that had once felt safely behind the lines. Some had been nurses attached to field hospitals. Others were clerks, cooks, laundry workers, telephone operators, or simply civilians who had followed husbands or units to the tropics in the early years of victory. A few, kept on no official roster, had been “comfort women”—classified in ways that left them with no rights and no protection when the front collapsed.

When the last Japanese officers had slipped away toward the interior or toward the sea, they had not taken these women with them.

They left no instructions except the ones that had been drilled in since training: Never be captured. Better to die by your own hand than face the enemy. The Americans, they had been told, executed prisoners out of hand. Those they did not kill, they humiliated. For women, the warnings were worse—spoken in blunt words behind closed doors, dripping with fear and disgust.

So when the first American patrol appeared at the edge of the trees, rifles at the ready, the women stiffened and waited for shots.

No one fired.

The U.S. soldiers approached slowly, muzzles lowered just enough to keep their fingers on triggers but not enough to look like a firing squad. They called out in English first, then in broken Japanese, asking if there were soldiers hiding nearby, if anyone was armed.

There were no men. No weapons. Just two hundred women in torn uniforms and civilian blouses, faces gray with fatigue, eyes stark with the hopeful hopelessness of people who have run out of options.

Once the Americans were sure there were no hidden rifles, they slung their own weapons or rested them on their shoulders and signaled for vehicles. The women were herded to a makeshift clearing under armed watch. Every movement—every shouted order to “sit” or “wait”—confirmed the women’s worst expectations.

This is where they shoot us, one nurse thought, glancing at the tree line. The space was large enough for a mass grave.

Instead, the Americans brought water.

Metal containers clanged as they were hoisted from jeeps. Blankets came next—coarse wool in dull colors, but a world better than the rags many of the women wore. Medics arrived carrying canvas bags. They moved down the line, asking through an interpreter about fevers, wounds, dizziness. Blood pressure cuffs squeaked. Thermometers were shaken and stuck under tongues. The women watched, rigid, as their pulse was counted, their bandages changed, their blistered feet examined.

They’re only making sure we’re healthy enough to kill, someone whispered.

Then the smell changed.

It drifted out of metal containers when the lids were pried off: warm steam carrying a scent none of them had ever quite encountered, though it felt instantly understandable. Fat and bread and something darker—cooked meat.

An American sergeant unwrapped a bundle of waxed paper and handed it to the first woman in line. She stared, hands hovering.

Inside, nestled in the folds, was a round of soft bread and a dark, warm patty. Not a rice ball. Not dried fish. Something entirely foreign.

He gestured, making a motion with his hand—bite, chew. “Eat,” he said. “It’s food.”

She took a cautious bite. The bread was soft; the meat juicy and seasoned. The flavors were heavy and unfamiliar, but her stomach recognized them before her mind did. Hunger that had gnawed at her for days surged, and she took another bite, faster now.

Around her, other women slowly unwrapped their own paper bundles. The clearing filled with the quiet sound of chewing, the tearing of bread, the low murmur of surprise.

Hamburgers, though they didn’t yet know the word.

After the sandwiches came bottles—dark glass with script painted in a foreign alphabet. The women turned them in their hands, confused. A soldier demonstrated how to use a simple opener, the caps popping off with a crisp metallic snap. He tilted the bottle to his lips, drank, then nodded to them.

The first sip of Coca-Cola startled more than one woman. The fizziness bit at their tongues and rushed up their noses; the sweetness was almost violent after years of bitter tea and watery soup. A nurse sputtered, then laughed, the shock cracking something tight in her chest.

It might have been the strangest moment of her life: standing in a jungle clearing, wrapped in a blanket given by the enemy, eating a soft, greasy sandwich and drinking a cold, sparkling, utterly incomprehensible foreign drink instead of kneeling in front of a firing squad.

The fear did not vanish. It simply found itself sharing space with confusion.

They were loaded into trucks and driven to a field camp set up behind the lines—a temporary place of tables, tents, and procedures. There, the pattern repeated itself.

A screened-off corner was marked for female prisoners. Names, ages, and hometowns were written down by interpreters who strained to record each unfamiliar syllable. Dehydration and malnutrition were noted at rates that did not surprise the American medics. The women were examined, not ogled. Wounds, some festering for weeks, were cleaned and wrapped.

When food came again—a plate of stew, a piece of bread, a wedge of canned fruit—the women ate more quickly, but the same thought circled in their minds.

They are feeding us. Why?

Days blurred as they waited to learn their fate. The routines of the temporary camp—roll call, meals, rest periods—felt disorientingly stable. No one was dragged away at night. No one was pulled out and beaten for some imagined slight. The suspicion that had kept their shoulders tight began to shift into a guarded curiosity.

After several days, a new convoy formed. This one took them not along muddy island roads, but toward a coastal harbor. Ships waited. Their destination was not the mainland of Japan, but a larger American-controlled facility farther away—Saipan, Guam, Hawaii, perhaps later the United States itself.

The permanent camp was larger than anything they’d seen since leaving home. Rows of wooden barracks stood inside fences laid out in exact rectangles. A central mess hall. A building for administration. A medical station. Guard towers. A flag flapped overhead in a wind they felt more than heard.

When the trucks stopped, women stepped down, blankets over their shoulders, clutching the bottles of water and the few possessions they’d been allowed to keep. The yard smelled of dust, cooking fat, and disinfectant.

They were marched to barracks reserved for women. Inside, neat rows of metal-framed beds waited with narrow mattresses and folded blankets. Footlockers sat at the end of each cot. Nothing was luxurious. Every plank and mattress screamed “military requisition” rather than comfort. But it was all intact. It was all in order.

The first meal in the new mess hall was like something from a repeating dream. Trays slid along rails. Ladles plopped stew, potatoes, vegetables, and canned fruit into compartments. Bread filled an entire basket. No one glanced twice if a prisoner went back for a second piece.

The women noticed that the soldiers took their meals too, but with a familiarity that made them seem almost careless—standing as they ate, talking with their mouths half full, drinking coffee from big white mugs.

Routine followed: roll call at dawn, breakfast, health checks, work assignments, lunch, chores, mail call where the Red Cross announced whether any families had been located. There were rules: no wandering unescorted, no hoarding food, no leaving barracks after lights out. The punishments for breaking them were mostly restrictions, not the savage beatings Imperial officers back home had shrugged off as corrective.

They earned small allowances for their work, paid in coupons redeemable at the camp canteen. The first time they stepped into that little shop—a wooden shack with shelves lined neatly—they stared. Soap. Toothpaste. Stationery. Occasionally hard candy in cellophane. Bottled soda, labels bright even under dim lights.

Coca-Cola, again.

Several of them couldn’t help it; the corners of their mouths tilted. A short laugh here or there. A joke in Japanese: “The enemy’s medicine.”

Work details took the women outside the wire under guard.

They weeded gardens carved out of cleared land near the camp’s edge. They sorted vegetables—onions, cabbages, potatoes—under makeshift awnings. They patched uniforms and mended torn blankets. Their fingers, used to needle and thread, adapted quickly. The tasks weren’t heavy but filled the hours.

They saw Americans moving beyond the fences. Trucks full of supplies. Jeeps with officers. Local farmers bringing in produce or taking away scrap. Once, a group of schoolchildren walked past with a teacher; the children stared at the Japanese women working among the rows, then waved shyly. One of the prisoners raised a hand before she could think better of it.

At midday in the fields, lunches arrived in big metal cans and boxes: sandwiches, pieces of fruit, canteens of water or weak tea. Sometimes the sandwiches had a thin slice of meat between slices of bread. Other times a familiar shape appeared again: a small patty of meat squeezed between two pieces of bread.

It wasn’t the same as that first hamburger on the island. It was simpler, less carefully assembled. But the women recognized it instantly. It was quick to eat, easy to hand out, practical in a way that fit everything else about the camp.

They took bites and tasted not only the food, but a strange sense of continuity. What had once been a symbol of terrifying uncertainty was becoming something else: a marker of routine.

Coca-Cola often appeared in a chipped metal bucket filled with ice. The sight of frost on the glass surprised them almost as much as the bubbles had the first time. They lined up, took their bottle, fumbled with the opener until they learned the trick. Even those who didn’t like the sweetness much drank it for the cold.

They watched how American soldiers ate, too—leaning on shovels or sitting on crates, talking about home or baseball, taking big bites and swigging from bottles without ceremony. No formal setting. No rice bowls or lacquered trays. Just food as fuel, gulped between tasks.

To the women, who had grown up with carefully arranged meals—rice here, soup there, three or five small dishes of vegetables and fish—the American way seemed casual, even careless. But its reliability was undeniable. Meals came when they were supposed to. Work started and ended on time. Medicine was given out according to the same schedules each day.

The camp’s predictability was its own kind of revelation.

Over months, fear of sudden execution faded. In its place grew a quieter, more complicated emotional knot: guilt at eating regularly when their families back in Japan were enduring famine; confusion at being kept alive and even made healthier by people their own government had described as demons; a growing awareness that the Americans were not improvising kindness, but following rules almost as strict as the ones that had governed prewar school assemblies.

They learned words. Breakfast. Supper. Queue. Soap. They learned that the strange English word “okay” could mean many things: agreement, reassurance, sometimes a gentle end to a conversation.

They learned that the Red Cross emblem carried power. With it came letters, a neutral guarantee. Without it, they imagined their fate would be different.

They learned that the men and women in uniform who watched them were not all alike; some were stern and distant, some quietly sympathetic, some brusque in a way that hid how carefully they always made sure no one was left out at mealtimes.

And they never forgot that first afternoon—the steaming bundles of bread and meat pressed into their hands when they had been certain they were about to die.

From that moment on, the taste of a hamburger and the sting of soda fizz were forever tied, in their minds, not just to American culture, but to the day their world tipped from terror into something harder to name: survival under unexpected rules.

When they eventually boarded ships to go back to a shattered Japan—to cities burned flat, to families reduced to names on casualty lists, to neighbors who looked at them with suspicion and asked, “What was it like with the enemy?”—most of them did not tell the full story.

They said they were prisoners. They said there was enough food. They rarely said “We had meat” or “We were given chocolate and soda.” That felt like another kind of betrayal.

Yet in their private writing, if they wrote at all, the memory surfaced again and again:

A line of women in torn uniforms, braced for the end.

Steam rising from a container.

Warm bread in the hands.

A foreign soldier gesturing, simply: eat.

Years later, one of them summarized it in a sentence that baffled her grandchildren: “Kindness is more dangerous than cruelty,” she wrote. “It can make you question who you have been willing to be.”

In a war defined by fire and steel, their story did not change the outcome of campaigns or the shape of the peace treaties. But for the women who tasted American hamburgers and Coca-Cola on the day they thought they would die, it changed something perhaps just as important: the edges of the word “enemy,” and the recognition that sometimes the deepest cracks in belief are opened not by force, but by a meal handed across a line that was never supposed to carry anything but bullets.

News

(CH1) FORGOTTEN LEGEND: The Untold Truth About Chesty Puller — America’s Most Decorated Marine, Silenced by History Books and Erased From the Spotlight He Earned in Blood 🇺🇸🔥 He earned five Navy Crosses, led men through fire, and left enemies whispering his name — yet most Americans barely know who Chesty Puller really was. Why has the full story of this battlefield titan — his brutal tactics, unmatched loyalty, and unapologetic grit — been buried beneath polite military history? What really happened behind closed doors during the fiercest battles of WWII and Korea? And why has one of the Marine Corps’ most legendary figures been all but erased from modern memory? 👇 Full battle record, unfiltered quotes, and the shocking reason historians say his legacy was “intentionally softened” — in the comments.

Throughout the history of the United States Marine Corps, certain names rise repeatedly from battlefields and barracks lore. Many belong…

(CH1) A 19 Year Old German POW Returned 60 Years Later to Thank His American Guard

In the last days of the war, when Germany was nothing but smoke and road dust, a nineteen-year-old named Lukas…

Woman POW Japanese Expected Death — But the Americans Gave Her Shelter

By January 1945, Luzon was on fire. American artillery thudded across the hills. Night skies flickered with tracer fire. Villages…

(CH1) Female Japanese POWs Called American Prison Camps a “Paradise On Earth”

By the winter of 1944, the war had shrunk the world down to barbed wire and fear. Somewhere in the…

6 months dirty. Americans gave POWs soap & water. What happened next?

On March 18th, 1945, when the transport train finally shrieked to a halt outside Camp Gordon, Georgia, Greta Hoffmann pressed…

(Ch1) Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

When the headline caught his eye, Eric Müller thought at first he had misread it. “President criticized for policy failures.”…

End of content

No more pages to load