By the time Aaron Blake turned thirty-five, his life had shrunk down to the squeak of a broom on linoleum and the soft weight of his son asleep on his shoulder.

The school gym was his kingdom.

He knew every scuff on the basketball court, every flickering light, every stubborn spot on the bleachers that needed an extra scrub. In the mornings he mopped hallways. In the afternoons he set up chairs. At night, when the events ended and the laughter faded, he swept away the confetti and crumbs and gum wrappers people left behind.

He didn’t complain. Not out loud, anyway.

Five years earlier, Jonah’s mother had walked out with a suitcase and no explanation that made sense. Aaron had gone from forklift operator to single parent overnight. The factory laid him off six months later. The janitor job at Lincoln Middle School was the first steady thing that came along.

“Better than nothing,” he’d told his reflection in the bathroom mirror, tie crooked, eyes tired.

He didn’t know then how much “better” it would become.

On that particular Friday, the gym buzzed.

It was the afternoon of the spring dance. Teachers and a few parent volunteers scurried around with ladders and rolls of tape, stringing paper lanterns from the rafters. Someone tested the speakers; a burst of pop music echoed off the walls before the tech teacher cut it off again. The air smelled like dust and cheap punch.

In the corner, Aaron moved with quiet efficiency, broom in hand, making wide arcs across the floor.

Sweeping was the kind of work that didn’t invite talking. He liked that. Words had felt too heavy lately, like boxes he didn’t have the energy to lift.

Across the gym, by the bleachers, his five-year-old son, Jonah, lay curled up on a folded sweatshirt, thumb in his mouth, the day finally catching up to him. He came to work with Aaron most afternoons, coloring in worn-out notebooks or racing toy cars along imaginary tracks while his father worked.

Life had become a quiet rhythm: sweep, carry, soothe, repeat.

As he pushed the broom into a neat pile of dust, he heard a soft sound behind him.

Not the clatter of a ladder or the squeak of sneakers.

The gentle whirr of small wheels.

He turned.

A girl about thirteen rolled slowly toward him in a wheelchair.

She had a halo of pale hair pulled back with a headband, eyes the color of rain on glass, and hands that gripped the wheels with cautious control. A lavender dress lay over her knees.

Aaron recognized her face. He’d seen her in the hallways, in the library, always with an aide or her mother close by. She was one of the kids who watched the world from the edges, present but never quite included.

She stopped a few feet away from him.

“Hi,” she said.

Her voice was soft, the kind that sounded like it apologized for taking up space. But underneath the timidity, there was something else—something steady.

“Hey there,” Aaron replied, leaning on his broom handle. “You excited for the dance?”

She hesitated. Her gaze dropped to the floor, then came back up.

“Do you know how to dance?” she asked.

He snorted before he could stop himself.

“Me?” He looked down at his stained work shirt, scuffed boots, and the broom in his hand. “I just make the floor shine. I leave the dancing to you kids.”

She didn’t laugh.

“I don’t… have anyone to dance with,” she said quietly. Her fingers picked at the seam of her sleeve. “All my friends are going with friends. Or… with people they like.”

Her cheeks colored.

She took a breath.

“Would you dance with me?” she asked. “Just for a minute. Before everyone comes.”

The question landed between them like something fragile.

Aaron glanced toward the stage, where a teacher was shouting about extension cords. Toward the clock, ticking closer to dismissal. Toward his son, asleep on his sweatshirt.

Then he looked back at the girl.

She might be thirteen, but the look in her eyes—hope fighting with the expectation of being turned down—was one he knew too well.

He set the broom aside.

“Tell you what,” he said, walking over and offering his hand. “I don’t know any of the new moves, but I can manage a slow spin. That work for you?”

She smiled, just a little.

“That would be… nice,” she said.

He moved behind her chair and gently rolled it to the center of the gym, between clusters of half-hung lanterns and the still-silent speakers. The polished wood gleamed under the fluorescent lights.

There was no music.

So he hummed.

It was an old tune—something his mother used to play on the radio when she cleaned the house on Saturdays. A melody that felt like sunshine through curtains and the smell of lemon dusting spray.

He placed a hand lightly on the back of her chair and began to sway, walking in slow circles, guiding her gently across the floor.

She laughed, startled by the movement, then let herself relax. Her hands lifted from the wheels, dress swishing slightly as they turned.

“You’re good at this,” she said.

“Don’t tell anyone,” he replied. “I’ve got a reputation to uphold.”

For a minute, the rest of the world fell away.

There were no volunteers, no tangled strings of lights, no bills waiting in the mailbox. There was just a girl spinning in her chair and a man humming an old song, sharing a piece of something neither of them could name.

They weren’t “the janitor” and “the girl in the wheelchair.”

They were just two people dancing.

In the doorway, unseen by them, a woman stood very still.

Caroline Whitmore was used to being in control.

Elegant in a navy blazer and heels that clicked authoritatively on tile, she was the kind of woman people noticed in boardrooms and charity luncheons. She ran meetings, signed off on budgets, and sat on the board of a foundation that funded programs for children with disabilities.

She was also a mother.

For thirteen years, she’d fought wars no one saw. Against doctors who underestimated her daughter. Against stares in grocery stores. Against systems that saw a wheelchair before they saw a child.

She’d built walls around Lila—strong, high walls made of vigilance and advocacy—to keep out pity, cruelty, and the thousand little cuts of being treated as “less than.”

Lately, she had begun to wonder if the walls kept out joy, too.

That afternoon, she’d come early to the school to drop off Lila’s medication and spare clothes, prepared—as always—for anything. She’d gone to the main office first, then wandered down to the gym, a habit born from wanting to see the room before the chaos.

When she reached the doorway, she stopped short.

Out on the floor, under half-hung lanterns, her daughter was spinning.

Not alone. Not in a circle of well-meaning adults talking over her head.

With the janitor.

Caroline recognized him. She’d seen him sweeping in the mornings, nodding politely in hallways, keeping a watchful eye on a little boy who often trailed behind him.

She watched as he hummed, as he guided Lila gently across the floor, as her daughter laughed—full and free—in a way Caroline hadn’t seen in too long.

No one was taking pictures.

No one was watching, except her.

He wasn’t performing kindness; he was simply being kind.

The prickling behind her eyes surprised her.

She blinked it away, stepped back before they could see her, and told herself she’d just come back later, when the dance was closer to starting.

But she couldn’t shake the image.

That evening, the gym transformed.

Lanterns glowed softly overhead. Music bounced off the walls. Kids poured in wearing too much cologne and not enough coordination, limbs flailing, sneakers squeaking. Teachers hovered along the edges, equal parts chaperone and referee.

Aaron stood by the bleachers, broom exchanged for a folding chair, Jonah perched beside him with a juice box.

He didn’t belong to this part of the night. His work was usually done by sunset.

But the principal had asked if he’d stay, “just in case we need an extra pair of hands.” Extra pairs of hands were what Aaron specialized in.

Out on the floor, he spotted Lila near the refreshments table, her chair now adorned with a small ribbon someone had tied on. A few classmates had stopped to talk to her. One girl showed her something on a phone; they laughed. No one danced with her. Not yet.

The DJ switched tracks. A slow song began.

Lila sat a little straighter, eyes scanning the room, hope flickering like the colored lights.

No one approached.

Aaron felt an urge to move, to cross the gym again, but stopped himself. This was her moment now, her choice.

Then he saw Caroline.

She crossed the room with her usual composure, but when she reached Lila, she knelt down, said something that made the girl’s face soften. They swayed together for a few seconds in an awkward, standing-leaning-to-sitting compromise.

Lila glanced toward the bleachers once.

When she saw Aaron watching, she raised her hand and gave the tiniest wave.

He waved back.

Later, when the lights came up and kids scattered like confetti, Aaron began his usual work of restoring order from chaos. He was halfway through folding chairs when he heard the click of heels again.

“Mr. Blake?”

He turned.

Up close, without the armor of a blazer and crowd, Caroline looked smaller. Not in stature, but in the way tiredness softened the sharp lines of her face.

“Yes, ma’am?” he said, straightening up.

She offered a hand. “I’m Caroline Whitmore,” she said. “Lila’s mother.”

He wiped his palm on his pants, suddenly conscious of the sweat and cleaning solution, and shook her hand.

“It’s nice to meet you,” he said. “Your daughter’s a great kid.”

“She is,” Caroline agreed. A smile flickered. “She told me something tonight I thought you should hear.”

He waited.

“She told me,” Caroline said, “‘Mom, someone made me feel like a princess.’”

His ears went hot.

“It was nothing,” he said quickly, looking down. “We were just killing time while everyone set up.”

“It wasn’t nothing to her,” Caroline replied. “Or to me.”

She hesitated—a beat longer than a CEO usually allows herself, he imagined.

“I’d like to take you to lunch,” she said. “Lila wants to thank you in person. And I… have something I’d like to talk to you about.”

He almost refused.

Lunch with someone like her—someone who had assistants and appointments and probably never had to staple her own forms—sounded like stepping into a world he didn’t belong in.

But he thought of Lila’s laugh in the empty gym.

And Jonah, watching from the sidelines, learning every day from what his father did and didn’t do.

“Lunch,” he said slowly. “We can do lunch.”

They met at a small café two blocks from the school.

Jonah swung his legs under the table, eyes wide at the sight of a pancake bigger than his head. Lila sipped cocoa, her hair loose around her shoulders, her chair angled so she was part of the triangle, not parked at its edge.

“So you’re the famous Mr. Blake,” Caroline said, stirring her coffee.

“He’s just Dad,” Jonah said through a mouthful of syrup.

Aaron chuckled. “He’s right.”

Between bites and sips, they talked. Not about policies or procedures, but about Lila’s favorite books, Jonah’s obsession with dinosaurs, the best way to get glitter out of gym floor cracks.

After the plates had been cleared, Caroline folded her hands on the table.

“I didn’t just invite you here to say thank you,” she said. “Though I am deeply grateful for what you did.”

Aaron’s brow furrowed. “Okay…”

Caroline took a breath in that measured way people do when they’re shifting from small talk to something that matters.

“I run a foundation,” she said. “It funds programs for kids with disabilities. Camps, mentorship, adaptive sports, art. That sort of thing.”

He nodded, not sure where this was going.

“We do good work,” she went on. “But lately I’ve been feeling like something’s missing. We have fantastic therapists, teachers, administrators. What we don’t seem to have enough of are people who… just see kids. As kids. Not projects. Not problems. Not miracles or tragedies. Whole kids.”

Her eyes met his.

“My daughter came home from that dance and said, ‘Mom, he didn’t look at my chair first. He just looked at me.’”

Aaron swallowed.

“I’m looking for someone to help us develop new programs,” Caroline said. “Outreach. Activities. Support for families. Someone who knows what it is to struggle, but doesn’t bring pity to the table. Someone who has their feet on the ground and their heart in the right place.” Her lips quirked. “Someone who can make a thirteen-year-old feel like a princess with a broom and a hummed tune.”

He blinked.

“I’m a janitor,” he said.

“You’re a father,” she countered. “You’re someone who shows up. Who listens. Who doesn’t flinch from hard work. Those skills translate better than you might think.”

He floundered for words.

“I don’t… have a degree,” he said. “I barely got through community college before life… happened.”

“We can teach you the paperwork,” she said. “We can’t teach heart. You already have that.”

He glanced at Jonah, who was now carefully stacking creamers like building blocks.

“What would I even do?” he asked quietly.

“Learn,” Caroline said. “Help us build things that work. For kids like Lila. For kids like Jonah. For parents who are where you’ve been.”

He sat back, the weight of the offer settling on his shoulders. It felt heavier than any mop bucket—and lighter, too, in a way he couldn’t explain.

“You don’t have to decide now,” she added. “Think about it. Talk to your son. But know this is real. It’s a salaried position. Benefits. Flexible hours. Training. We’d start you as a program coordinator and see where you grow.”

“Why me?” he asked.

She smiled.

“Because you treated my daughter like a person,” she said. “That’s rarer than it should be.”

He didn’t decide that day.

Or the next.

Change was frightening. They had just gotten used to the rhythm of his current job—his early mornings, Jonah’s afternoons at the gym, the predictability of paychecks no matter how small.

But late at night, when Jonah was asleep and the house was quiet, Aaron found himself thinking about the kids he saw at the foundation’s website—faces of all colors, bodies with braces and wheels and walkers, eyes lit up with some combination of mischief and hope.

He thought about the exhaustion etched into the faces of their parents in the background.

He thought about how Lila had laughed in the gym.

And how good it had felt to make someone’s world bigger, even for just a minute.

A week later, he walked into Caroline’s office with his résumé—a flimsy piece of paper with more years of “maintenance” than anything else—and a knot of fear in his stomach.

He walked out with a job.

The first months at the foundation were hard.

He sat in meetings where people tossed around terms he’d never heard before—sensory integration, IEPs, therapeutic recreation. He learned to use spreadsheets. He fumbled through emails, rereading them three times before hitting send.

But he also did what he’d always done best: he paid attention.

He noticed when a kid’s shoulders tensed at a certain noise. When a parent’s smile was too bright, covering something brittle. When staff, despite their best intentions, inadvertently sidestepped a child or talked over them.

He suggested small changes. Different lighting at events. Quiet corners with beanbags. Simple language on flyers. He brought in the idea of “buddy dances” at school functions—pairing students of all abilities to choose each other, not be chosen.

He started a Saturday playgroup for kids whose parents couldn’t afford expensive programs. He made up games on the fly and roped Jonah into being a junior helper.

There were setbacks.

He doubted himself a lot.

But slowly, he watched things shift.

Kids who had stared at their hands in their laps began to roll or walk or run toward activities. Parents began to exhale when they entered the building, shoulders dropping as they realized they didn’t have to be on guard every second.

And Jonah—his sweet, hopeful boy—thrived. Surrounded by role models of all kinds, he learned empathy without pity, patience without condescension.

One evening, almost a year after that dance, Aaron found himself standing on a small stage at the foundation’s annual gala, wearing a suit he’d borrowed from Caroline’s husband and a tie his son had picked out.

Lights warmed his face. The room beyond was full of clinking glasses, murmured conversation, and people in clothes that cost more than his first car.

He cleared his throat.

“I used to sweep floors for a living,” he began. “I still do, sometimes. Old habits.”

A ripple of polite laughter.

“Not that long ago,” he said, “my life was about keeping things clean and quiet and out of the way. I thought the best I could do was make spaces nice for other people and make sure my boy was safe.”

He glanced out into the crowd.

His eyes found Lila, sitting near the front, wearing a blue dress with stars on it, listening intently. Next to her, Caroline tilted her head, pride softening the usual sharpness of her features. Off to the side, Jonah, now six, waved when his father’s gaze met his.

“One night in a school gym,” Aaron continued, “a girl asked me to dance.”

He told the story simply—the broom, the empty floor, the question that had caught him off guard. He talked about how small moments can be turning points, even when you don’t realize it at the time.

“How we see each other,” he said, “matters. Whether we look first at what someone can’t do—or what they can. Whether we see a wheelchair, or a kid who wants to feel like a princess for three minutes at a dance.”

He swallowed.

“I didn’t change Lila’s life that night,” he said. “But she changed mine.”

The applause that followed wasn’t thunderous. It wasn’t the roar of a stadium. It was steady, sustained, warm.

The kind that says we see you.

Years later, the school gym didn’t smell as much like dust.

It smelled like popcorn and crayons and that strange, indescribable scent of many children playing together in one room.

The paper lanterns had been replaced by strings of lights donated by a local hardware store. The speakers were newer, the playlist more chaotic. A ramp had been added to the stage. The “NO FOOD IN GYM” signs had been quietly ignored for this one special evening.

Kids of all abilities ran, rolled, walked, and hopped across the floor.

In one corner, Jonah—now lanky and perpetually hungry—led a group in some absurd dance move he’d probably learned online. Lila, a little older, sat in her chair surrounded by a circle of younger kids, book in hand, reading aloud with dramatic flair. They hung on her every word.

On the sidelines, parents chatted without constantly scanning for danger. Staff moved in easy patterns, stepping in when needed, stepping back when not.

Near the doorway, under those same rafters where paper lanterns had once hung crookedly, Aaron and Caroline stood side by side.

He wore a polo shirt with the foundation’s logo. She’d kicked off her heels hours ago and stood barefoot, her blazer draped over a chair.

“Remember the first time you saw this gym?” she asked.

“Empty. Sticky,” he said. “Smelled like stale sweat and floor polish.”

“And now?” she prompted.

He watched as a kid with a walker and a kid with light-up sneakers engaged in a serious race to the far wall, both grinning. Another pair—one child with noise-canceling headphones, one without—sat under the bleachers playing cards.

“Now it feels full,” he said. “Like it always should’ve.”

Caroline nodded, eyes shining.

“That night,” she said, “I watched you dance with my daughter and I thought, ‘Here’s a man who doesn’t know how important what he’s doing is.’”

“I still don’t,” he said. “Half the time I feel like I’m just making it up as I go.”

“Welcome to leadership,” she replied dryly.

They both laughed.

Across the room, a little girl hesitated at the edge of a circle of kids playing a game. Lila caught her eye, held out a hand, and the girl moved closer, encouraged.

“Do you ever think about how all this started?” Caroline asked softly.

He nodded.

“Every day,” he said. “With a broom and a question.”

He didn’t think of himself as a hero. He still swept floors sometimes, by choice. It reminded him of where he came from. Of the quiet places where kindness lives.

He’d learned something since that cold, tired afternoon when a girl in a wheelchair rolled up to him in an empty gym and asked if he knew how to dance:

Kindness doesn’t need an audience.

It doesn’t need a job title or a paycheck or a plaque.

It just needs someone willing to put down their broom, see another person clearly, and say yes to a small, courageous question.

Sometimes, that yes turns out to be the first step in a much bigger dance than you ever imagined.

News

He missed the most important job interview of his life—but that same day, he unknowingly saved…

The morning sun glinted off the glass towers of downtown Chicago as Malik Johnson tightened his tie and checked his reflection in…

My brother shattered my ribs. My mom whispered, ‘Stay silent. He still has a future.’ But my doctor didn’t hesitate. And that’s when the truth exploded..

I was seventeen the summer my brother crushed my ribs. It happened in our Texas living room on a day…

My Family Made Me Their Servant but When My Secret Billionaire Boyfriend Showed Up at the Wedding, I Finally Watched Their Fake Reputation Collapse in Front of Everyone’s Shocked Eyes.

I knew the night was going to be bad when my mother handed me a stained apron and whispered, “Don’t…

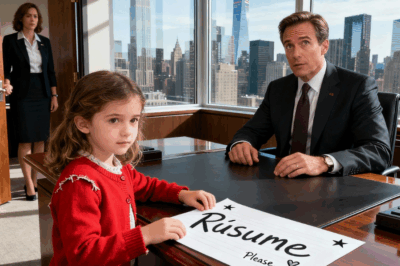

The little girl walked into the millionaire CEO’s office with a résumé and a single sentence that brought him to tears…

Little Girl walked into the Millionaire CEO’s office with a resume and one sentence that made him cry. Daniel Hayes…

When the billionaire found his maid asleep in his bedroom, his surprising reaction set off a wave of curiosity.

The Sleeping Maid and the Billionaire’s Promise The room was silent. Sunlight poured through the tall glass windows, brushing the…

My pregnant daughter showed up at my door at 5 a.m., bruised and trembling, while her husband called her “mentally unstable.”

I’ve spent twenty years of my life standing over dead bodies, listening to alibis that didn’t hold and lies that…

End of content

No more pages to load