The Trap at Mons

September 1944

Southern Belgium

Two tides were flowing across the fields.

One was ragged, gray, and moving east—70,000 German soldiers: stragglers, staff officers, cooks with rifles, the broken remains of three corps stumbling away from France, desperate for the safety of the Fatherland.

The other was green and steel and moving north—American armored columns, engines roaring, dust and exhaust trailing behind, pushing so hard that their supply trucks could barely keep up.

Both tides were headed toward the same crossroads.

A place most of them had never heard of.

Mons.

Neither side knew the other was there.

“Go as far as practicable”

Six weeks earlier, the front in Normandy had broken wide open.

Operation Cobra, at the end of July, had shattered German defenses west of Saint-Lô. After months of grinding hedgerow fighting, suddenly the U.S. Army was doing what it did best—moving.

Shermans, half-tracks, jeeps, and deuce-and-a-half trucks poured through the gap, racing across open country. Towns that had taken weeks to approach in June fell in days in August.

The German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army, hammered around Falaise, were reeling. Thousands had been killed. Tens of thousands captured. What remained west of the Seine looked less like a coherent force and more like a survivor column.

A U.S. report summed it up brutally: “exhausted, disorganized, demoralized.”

General Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. Twelfth Army Group, saw more than a victory. He saw a chance.

If he kept pressing, if his men drove “as far as practicable” east, maybe—just maybe—they could reach the Rhine before the Germans built a new line.

On August 27, his orders went out: don’t stop. Push. Take advantage of the chaos. Outrun your own logistics if you have to.

It was a calculated gamble: speed over stability, risk over consolidation.

The U.S. Army, with its high degree of motorization and training for mobile warfare, was built to gamble like that.

The Wehrmacht infantry, still relying heavily on horses and their own feet, was not.

A New Problem: Too Fast

By the end of August, American spearheads were approaching the Belgian border.

So, in their own way, were the German survivors.

Bradley noticed something worrying in the situation reports.

His armored divisions were moving so fast that they were beginning to overshoot pockets of retreating Germans. If he focused entirely on lunging east toward Germany, a lot of enemy units might simply slip away north and northeast, through gaps, to fight another day.

On August 31, he adjusted.

Instead of everyone racing toward the Rhine, he told one army—First Army under General Courtney Hodges—to swing north and cut across the German line of retreat.

The aim wasn’t to take ground.

It was to take away the roads.

Three Corps Pivot

Hodges issued his orders.

Three corps would turn north.

On the left, XIX Corps under Charles Corlett would push toward Tournai.

In the center, V Corps under Leonard Gerow would advance toward Landrecies.

On the right, VII Corps under J. Lawton Collins—the “Lightning Joe” who’d cracked the Normandy hedgerows—would wheel hard north toward Avesnes, Maubeuge, and Mons.

Collins wasn’t thrilled.

His eyes, like everyone’s, had been on the Siegfried Line—Germany’s western fortifications. But orders were orders.

So the 3rd Armored Division spearheaded the turn, columns of tanks and half-tracks stretching for miles, rolling past French farmers still blinking in the dust of liberation.

By September 2, those columns were near the Belgian border.

They didn’t know that almost directly in front of them, converging on the same area, was a German force roughly equal in size to an entire army.

Straube’s “Army” of Ghosts

On the other side of the lines, German command structure was in tatters.

On August 31, three corps commanders—LVIII Panzer Corps, LXXIV Army Corps, and II SS Panzer Corps—realized they’d lost contact with higher headquarters.

No orders were coming.

No clear picture of the front existed.

What they did have were tens of thousands of men marching east through northern France and Belgium like a broken river.

They banded together by necessity.

General Erich Straube took nominal command of the ad hoc group, an “Army Task Group” made of remnants of ten divisions, plus support units, drivers, cooks, signalers.

About 70,000 men in total.

They were battered.

Short of fuel.

Short of ammunition.

Short of sleep.

But Straube had a plan.

He’d pull them back toward Mons, use canals and the marshy ground nearby as a defensive screen, then pivot northeast toward Nivelles on foot, hopefully slipping between the American thrusts.

It meant marching 70 kilometers through a region he didn’t control.

It meant trusting that the Allies weren’t thinking about cutting sideways.

It meant gambling that speed—on tired legs—could outpace American speed on treads and wheels.

First Contact: A Sherman in the Dark

On the night of September 2, reality collided with plans in the worst way—for the Germans.

A German column—a mix of half-tracks, trucks, and marching troops—rolled down a straight country road near Mons in the dark, headlights blocked, the drivers hugging the verge by instinct.

At the far end of that same road, a Sherman tank from the 3rd Armored Division sat squarely across it.

A roadblock.

A shadow shape in the night.

The first German vehicle almost didn’t see it in time.

Swerving, braking, confusion rippled backward through the column.

American tanks nearby, engines idling, snapped awake.

Guns traversed.

The night lit up.

A U.S. round hit a vehicle near the front.

It exploded, flames billowing, turning the black road into a lantern that illuminated every truck and half-track behind it silhouetted like targets on a range.

“Like shooting sitting pigeons,” an American later said.

Shermans and tank destroyers fired down the length of the road.

Machine guns stitched the ditches.

By dawn, that mile-long column was wreckage.

Burning vehicles.

Bodies.

Equipment.

A road that had carried men fleeing to safety now marked an early grave for hundreds of them.

And it was only the beginning.

Mons: Liberated and Blocked

On the morning of September 3, elements of the 3rd Armored Division rolled into Mons.

Belgian civilians, having survived four years of occupation, poured into the streets.

Flags appeared from hidden places.

Wine bottles surfaced.

Cheering erupted.

The tankers enjoyed it—for a moment.

Then orders came down.

Celebrate later.

Block now.

Every road leading northeast out of Mons toward Avesnes had to be sealed.

Shermans took up positions at intersections.

Roadblocks of armor and infantry went up in hours.

Barely had they done so when scouts reported more German columns approaching—from the southwest, from the west, from the very direction Straube’s “army” was streaming in.

At the same time, on the far side, U.S. infantry divisions were closing in.

The 1st Infantry Division was pushing up from Avesnes.

The 9th Infantry Division held ground near Charleroi.

To the west, XIX Corps had cut Tournai.

To the south, V Corps held the line at Landrecies.

To the north, British units were racing to close the gaps.

The net was tightening without anyone initially realizing just how tightly.

The German columns, marching and riding by piecemeal in the countryside, began blundering into roadblocks they had no map for.

Confusion and Close Quarters

All through September 3, the same pattern played out again and again.

A German unit—company, battalion, sometimes an entire column—came up a road expecting distance between themselves and the Americans.

Instead, they hit a U.S. roadblock—tanks dug in hull-down, infantry in ditches.

Sometimes the Germans fired first, desperate to punch through.

Sometimes the shock of the encounter and their own exhaustion led to quick surrender.

An American report noted that the unexpected roadblocks threw German units “into confusion.”

They had no communications to coordinate.

No idea who was on their flanks.

No fuel to maneuver.

The fighting that did occur was often ugly and close.

At one point, Private First Class Gino J. Merli of the 18th Infantry found his machine-gun position overrun. As German troops swarmed past, he played dead in a pile of casualties. When they moved on, he’d crawl back to his gun and open fire again. He repeated this grim routine through the night.

When dawn came, more than fifty German bodies lay around his position.

Elsewhere, Belgian Resistance fighters joined the fray, guiding American units down back roads, harassing German stragglers, helping round up prisoners.

Above, the IX Tactical Air Command swooped in.

Stuck columns of vehicles made perfect targets for fighter-bombers.

Hundreds of German trucks and half-tracks burned under strafing runs and rockets, black smoke curling into a late-summer sky.

In the confusion, one German general wandered into a U.S. medical unit’s perimeter and was taken prisoner by astonished medics.

The Pocket Closes

By the afternoon of September 3, the scale of the trap was becoming clear.

In just those hours, the 3rd Armored Division and the 1st Infantry Division scooped up somewhere between 7,500 and 9,000 prisoners.

More came in waves.

Not all German units were encircled.

Straube and much of his headquarters staff slipped out early, moving ahead of the maelstrom.

Some combat units managed to blast through the tightening ring, suffering heavy casualties but making it east.

But the bulk of his provisional “army” found itself hemmed in by enemies they’d not even been sure were in the region.

On September 4, the 3rd Armored pulled off—its job done, its northward detour complete. It turned back east to chase the big prize: Germany itself.

The 1st Infantry Division stayed to finish the job.

On September 5, near Wasmes, the 26th Infantry Regiment faced something almost anticlimactic: a group of 3,000 Germans who surrendered en masse.

Tired men.

Hungry men.

Men who understood, finally, that the fight in this pocket was over.

By that evening, the Mons Pocket ceased to exist as a coherent battle.

It was ruins, wrecked vehicles, prisoner cages.

And empty roads ready for new orders.

Tallying Up

The numbers were stark.

In the Mons area—within just a few days—the Americans captured about 25,000 German soldiers.

It was the second-largest bag of prisoners in the 1944 Western campaign, trailing only the roughly 45,000 captured in the Falaise Pocket a month earlier.

German casualties in killed and wounded ran to around 3,500.

Captured equipment included:

About 40 armored vehicles

100 half-tracks

120 artillery pieces

And nearly 2,000 other vehicles

For the Americans, the cost was comparatively light.

The 3rd Armored Division lost 57 men.

The 1st Infantry Division: 32 killed, 93 wounded.

Equipment losses?

Two tanks.

One tank destroyer.

Twenty other vehicles.

In exchange, they tore a 75-kilometer-wide gap in the German line.

The road to the Siegfried Line, at least on map paper, lay open.

“Ten Days”

On September 6, General Hodges, buoyed by the victory and looking at enemy units in retreat and disarray, told his staff that if the good weather held, the war in Europe would be over in ten days.

He was wrong.

Fuel shortages, overstretched supply lines, and the stubborn geography of the German frontier slowed the advance to a crawl. The Germans, once back near their own border, found their footing in old fortifications.

By September 10, their line from the North Sea to Switzerland had stiffened again.

It would be March 1945—six months later—before Allied troops finally crossed the Rhine in force.

Even so, Mons mattered.

Not because it ended the war, but because it showed something reassuring to one side and terrifying to the other:

The U.S. Army could now conduct mobile warfare as brutally, efficiently, and decisively as anyone.

It could turn fast-moving pursuit into encirclement.

It could slam a gate on an enemy trying desperately to run through it.

For the men who were there—American tankers watching columns surrender, German infantrymen stumbling into roadblocks they hadn’t known existed—Mons was less a neatly labeled “pocket” on a map than a sudden, disorienting realization:

The direction of the war had reversed.

The pursuers and the pursued had changed places.

And from that point on, in the West, it would stay that way.

The End.

News

“THEY’RE GOING TO DROWN US!” — Japanese Women POWs SCREAMED as Trucks Approached the River

On August 14th, 1945, the canvas-covered trucks rattled to a stop beside a river in California’s Salinas Valley. Inside the…

“We Were Locked Up for Them” — German Women POWs Cried When U.S. Soldiers Refused to Touch

In April 1945, the war was almost over, but no one in the little German town of Lair knew exactly…

The Tank American Crews Asked For – Why the M26 Pershing Missed WWII’s Big Battles

July 27, 1944 Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone….

(CH1) The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks | Wet Stowage Explained

July 27, 1944Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone. The…

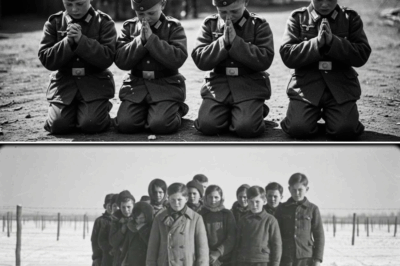

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Coca-Cola Instead

Story title: The Coca-Cola in the Snow The last days of the war tasted like dirt and metal. Thirteen-year-old Oskar…

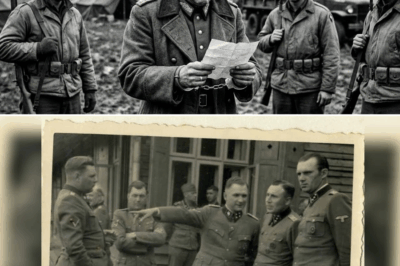

Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

Story title: From Lies to Headlines 1. Surrender with a Satchel of Lies May 8, 1945 Southern Bavaria The last…

End of content

No more pages to load