1. Capture in the Ardennes

April 16, 1945

Ardennes Forest, Belgian–German border

Dr. Gustav Yocom’s hands wouldn’t stop shaking.

Partly from exhaustion—seventy-two hours awake, if he was counting correctly—partly from the cold creeping through his damp boots, and partly from the simple fact that the war was over for him and he had no idea what came next.

He knelt in the mud beside Obergefreiter Hans Müller, nineteen years old, from some small town on the Rhine. The boy’s abdomen was open, intestines glistening in the thin morning light. Shrapnel had torn him apart.

Gustav had seen this wound six hundred times in the last four years.

He knew what it meant.

Without an operating theatre, without ether, without sutures, Müller would be dead by sunset.

There was no operating theatre.

The canvas of his field hospital, strung between three ruined trees, had collapsed under American artillery fire three hours ago. The morphine had run out days earlier. The last of the catgut had snapped on a corporal’s leg the night before.

Engines growled in the distance. American engines. Getting closer.

To Gustav’s left, the remnants of his company were already slipping away into the fog, gray uniforms dissolving into gray trees. Somebody shouted his name.

“Doktor! Komm! We have to go!”

He looked at the retreating shapes.

He looked at Müller’s white face.

He stayed.

It wasn’t heroism.

He was simply too tired to run.

War had carved him down to essentials. Ambition, fear, even hope had been stripped away. What remained was habit—a physician’s reflex: stop the bleeding, count the breaths, keep a heart beating a little longer if you could.

So when the Americans finally emerged from the trees—twelve men in olive drab, rifles raised, voices sharp—he did the only thing that felt honest.

He raised his bloody hands, pointed at Müller, and said the only English word he knew.

“Doctor,” he said hoarsely. Then, grasping for another, “Help.”

2. A Different Kind of Capture

The American sergeant at the front—a broad-shouldered man with “KOWALSKI” on his name tape—hesitated for half a heartbeat.

Then he lowered his rifle.

He barked an order over his shoulder. Two medics appeared as if conjured, stretcher between them. They moved past Gustav without pushing him aside, without a kick, without a curse. They knelt next to Müller, assessed the wound, and started working.

Within ninety seconds, the boy was on a stretcher, plasma dripping into his arm from a bottle held high. Within twenty minutes, he was in an American field surgical unit Gustav hadn’t even known was there, under a tent lit by electric bulbs powered by a humming generator.

Gustav stood outside the tent, his hands lashed behind his back with a plastic tie, and watched through the open flap.

They were doing everything he had wanted to do and hadn’t been able to.

Real ether hissed from a mask over Müller’s face—not the watered-down substitute Germany had resorted to since 1943. Blood plasma bottles stood in neat rows on metal shelves. The sutures they used were silk, not catgut scraped thin enough to snap if you pulled wrong.

In the corner, an X-ray machine hummed.

An X-ray machine.

In a field hospital.

What stunned him most wasn’t the equipment. It was the waiting.

There was no triage line outside. No desperate calculations about who would live, who would die, who had to be left to bleed because there weren’t enough supplies. No grim math dividing limited morphine doses among unlimited screams.

They treated Müller as if he were the only wounded soldier in the war.

As if the fact that he wore an enemy uniform was a detail, not a verdict.

The chief surgeon, a major with “THOMPSON” on his chest, caught Gustav watching.

He said something to a nearby lieutenant.

The lieutenant walked over.

In halting German, he asked, “Sind Sie Arzt? Are you a physician?”

Gustav nodded, throat too tight for words.

The lieutenant relayed this.

Thompson looked at him for a long moment, then said something else.

The lieutenant translated.

“He asks,” he said, “if you would like to observe the closure.”

The question made no sense.

Captured enemy doctors were to be interrogated. Processed. Shipped to POW camps. They were not invited to watch the enemy’s surgical technique.

“I don’t understand,” Gustav said in German.

The lieutenant’s lips moved, the answer coming back.

“You stayed with your wounded,” he said. “That makes you a doctor first, enemy second. Besides, we have more of yours coming. We may need your help.”

The plastic tie came off his wrists.

For the next sixteen hours, Dr. Gustav Yocom worked side by side with the men who had captured him, operating on Germans and Americans alike, under lights that never flickered, with supplies that seemed inexhaustible.

When his hands fumbled from fatigue, an American nurse steadied them without a word. When he needed a clamp, it appeared in his fingers before he finished asking.

At three in the morning, someone handed him a cup of coffee and draped a U.S. Army blanket over his shoulders.

“Here, Doc,” said a medic, smiling. “You look like hell.”

The coffee was hot and sweet.

He hadn’t tasted sugar in months.

He took a sip and felt tears cut clean tracks through the grime on his cheeks.

It was his second shock.

The first had been the morphine they’d given Müller without hesitation.

This was his second: an enemy putting sugar in his cup as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world.

It wasn’t mercy.

Mercy implied magnanimity, the strong stooping to help the weak.

This felt like something else.

Something closer to procedure.

3. Across the Ocean

Three weeks later, he was on a Liberty ship bound for America.

The journey went: truck to Liège, train to Le Havre, ship across the Atlantic. Two thousand German prisoners, all of them taken from the collapsing front, packed into holds that had carried Sherman tanks in the opposite direction months earlier.

Gustav slept in a makeshift infirmary, treating seasickness, infected cuts, and the sudden psychic collapse that hit men once they realized their war was over.

He expected the crossing to be terrifying.

U-boats still prowled. The Atlantic was vast and indifferent.

Instead, he felt an odd calm.

Some of it was exhaustion.

Some of it was the strange freedom of having no meaningful decisions left to make.

Some of it was the unsettling contrast between his expectations and what he was seeing.

Red Cross parcels arrived daily.

Chocolate.

Canned meat.

Cigarettes.

Powdered milk.

The portions weren’t generous by peacetime standards, but they were consistent. No one starved. No one fought over scraps.

Each man received two blankets.

He’d expected one, thin and insufficient.

The latrines were crude but cleaned daily by American servicemen, not by prisoners forced into humiliation hierarchies.

He kept waiting for the revenge to begin—to be lined up, beaten, spat on, degraded for what he represented.

He’d seen how the Wehrmacht treated Soviet prisoners.

He’d heard things—whispered, denied, and whispered again—about camps in the East.

Surely these Americans, whose sons had died by the hundreds of thousands, would harbor hatred enough to match.

It didn’t come.

On May 8th, when news crackled over the ship’s loudspeakers that Germany had surrendered unconditionally, the American guards handed out extra rations.

They unlocked the deck hatches so prisoners could come up and see the stars.

That night, Gustav stood on deck. The Atlantic stretched in all directions, black and slick, the ship’s wake glowing faintly with phosphorescence.

Below, German voices sang Lili Marleen into the dark, the old marching song rising and falling with the swell.

An American sailor, barely more than a boy, stood nearby on watch.

When the singing ended, the sailor pulled a harmonica from his pocket.

He played the melody back to them—slowly, respectfully—as if it were a hymn, not the song of an enemy army.

Gustav listened, the wind lifting the notes.

That was the moment he understood something.

This wasn’t a one-off kindness.

It wasn’t a clever trick to soften them up for interrogation.

The abundance. The Red Cross oversight. The casual humanity. The fact that he’d been allowed to do medicine again.

These weren’t exceptions.

They were how the system worked.

4. Camp Clinton

Camp Clinton, Mississippi, sprawled across 200 acres of pine forest—a grid of white-painted barracks, guard towers at intervals, barbed wire fences enclosing a city of fifteen thousand German POWs.

Compared to the front, it looked… orderly.

Compared to what he’d expected, it looked impossible.

The fences were real. The sentries carried rifles.

But the wire felt more symbolic than suffocating.

Within the compound, men moved freely, organizing soccer games, forming orchestras, tending gardens in small plots the administration allotted. They built little pieces of normality inside the confinement.

Within forty-eight hours of arrival, Gustav was in the camp hospital.

It was four connected barracks with plumbing that worked, lights that stayed on, and more medical supplies than he’d seen in the last year of war.

The chief medical officer, Captain David Bernstein, met him in an office where charts were stacked in neat piles.

Bernstein spoke German with a Bavarian lilt.

“My grandparents came from near Würzburg,” he said. “Long time ago.”

He slid a form across the desk.

“We need doctors,” he said. “Fifteen thousand men, all of them with bodies that break and cough and develop appendicitis, no matter what uniform they used to wear. You’ll work with our team. Same equipment. Same protocols.”

Gustav eyed the form.

“I am a prisoner,” he said cautiously.

“Legally,” Bernstein agreed. “Medically? You’re a physician. That’s the only status that matters in this building.”

“Why do you trust me?” Gustav asked. The question had been lodged in his throat since Belgium.

Bernstein looked up sharply.

“You took the Hippocratic Oath?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“So did I,” Bernstein said. “That comes before flags.”

He hesitated, then added quietly, “My cousin died in Dachau. I have every reason to hate you and anyone who wore your uniform. If I let that hate decide how I practice medicine, then the people who built Dachau win something they don’t deserve. They make me less of a doctor. I won’t give them that.”

The logic was clean.

Almost brutally so.

Something in Gustav’s chest loosened.

Here, in this place, his duty was the same as it had been under a different uniform: treat the patient in front of him.

That was a duty he understood.

5. Practicing Medicine for the Enemy

The work at Camp Clinton was relentless but never chaotic.

He treated dysentery, pneumonia, work injuries from construction details. He drained abscesses, set fractures, performed appendectomies and hernia repairs. Once, he did an emergency tracheotomy on a man who choked on a piece of meat in the mess hall.

The supplies never ran out.

If he requested sulfa drugs, a box appeared.

If he asked for more gloves, they were restocked the next day.

The electricity never failed.

The water always ran.

The shocks accumulated in small ways.

The American nurses called him “Dr. Yocom” without italics in their voices.

When he made a recommendation on a case, Bernstein would write it down and act on it. No one asked if he was loyal. They cared if he was right.

One evening in July, he assisted in surgery on an American guard with a hot appendix. As he sutured the incision, he realized he was closing up the belly of a man who’d been guarding him the day before.

Afterward, in the corridor, the guard nodded at him.

“Thanks, Doc,” he said.

Two syllables.

Thanks, Doc.

Spoken by a victor to a captured enemy, as casually as one might thank a barber for a neat haircut.

In August, when news came that the war with Japan had ended in atomic fire over cities whose names he’d never really thought about—Hiroshima, Nagasaki—the camp organized a celebration.

There was a band.

Extra food.

Permission for the prisoners to gather in the central square.

Gustav watched the Americans distribute ice cream in paper cups.

Ice cream.

In Mississippi.

In August.

To German POWs.

He took one.

It started to melt instantly, dripping down his fingers. He tasted it.

Real vanilla. Cold and rich and absurd.

Nearby, one of the guards was crying as he handed out the cups.

“Why are you crying?” Gustav asked in halting English.

“Because I’m going home,” the guard, Jensen from Iowa, said, wiping his eyes with the back of his wrist. “My little brother’s coming back from the Pacific. It’s over. Nobody else has to die.”

He laughed, embarrassed. “Feels stupid, getting emotional in front of you guys.”

“Not stupid,” Gustav said quietly.

That night, he tried to write to his sister Maria in Bremen.

He wanted to tell her about the morphine, the coffee, the ice cream, Captain Bernstein’s careful logic. About the fact that he, a German doctor, was being allowed to practice medicine at a level he’d only dreamed of in the Wehrmacht.

He could not find the words.

How do you explain that you’ve found more humanity among your captors than you ever did in your own army?

In the end, he wrote only:

I am well. The conditions here are good. There is hope.

6. Choosing America

In early 1946, the United States began to think about what to do with its hundreds of thousands of German prisoners.

Germany lay in ruins. The Soviet zone in particular was starving. America, by contrast, was gearing up for a postwar boom.

Someone, somewhere, came up with a program.

Prisoners with certain skills—mechanics, engineers, doctors—could apply to stay.

Not as prisoners.

As immigrants.

For Gustav, the decision wasn’t really a decision.

He filled out the forms.

Captain Bernstein wrote him a letter of recommendation.

So did an American surgeon who’d seen him operate.

By September 1946, Dr. Gustav Yocom was no longer prisoner-of-war 47,312.

He was an immigrant with a temporary pass, seventy-three dollars in cash, and a suitcase that contained two shirts, one suit, and his medical certificates.

He stood in a Greyhound station in Jackson, Mississippi, staring at a tangle of bus routes.

“Where you headed, hon?” asked the woman behind the ticket counter.

He groped for words.

“I… doctor,” he managed. “Need… work. Hospital.”

Her eyebrows rose.

“You one of them German doctors from Clinton?” she asked. “We had folks in from there before.”

He nodded, tense, waiting for the tightening in her face, the change in her voice.

Instead, she thought for a moment.

“Columbus, Georgia,” she said. “Fort Benning’s there. Army base. They always need doctors. There’s a German church too. Folks’ll help you settle. That sound all right?”

He nodded again, feeling foolishly close to tears.

She slid a ticket toward him.

“Four-fifteen,” she said. “Track two.”

Four dollars and fifteen cents.

The price of starting over.

7. Columbus

Columbus, Georgia, sat on the Chattahoochee River, just across from Phenix City, Alabama—a middle-sized Southern town whose fortunes rose and fell with the needs of Fort Benning.

It turned out to be a good place to disappear and build a life at the same time.

He found a room in a boarding house run by a widow who fed him biscuits and corrected his English with gentle humor.

He applied for a Georgia medical license.

There were exams.

Interviews.

Questions about his past.

Letters from Bernstein and others smoothed the way.

In January 1947, he received a piece of paper stamped with the state’s seal.

He rented two small rooms above a hardware store on Broadway.

A battered sign went up in the window: Dr. G. J. Yocom – General Practice.

His first patient was a Black woman named Esther Washington with a cough that had lingered for months. She worked as a maid. The colored hospital had turned her away; she couldn’t pay.

He charged her one dollar.

When it became clear even that was a struggle, he reduced it.

Within six months, his waiting room was full.

8. Medicine Across Lines

The South was a shock of a different kind.

Germany’s racism had been explicit, ideological. The American South’s racism was casual, deadly, woven into everything from bus seats to school boards.

There were separate waiting rooms at the big hospital downtown.

Separate water fountains in the courthouse.

Separate schools.

Separate, everything—under the lie of separate but equal.

Gustav watched Black patients come in through a side door to his office because that was what they were used to, and he told them they could sit in the same chairs as everyone else.

When a young Black man named Thomas Wright arrived with a knife wound gone bad because both the white and colored hospitals were “full,” Gustav treated him.

“You’ll need follow-up,” he said. “You come back. You pay what you can. If you cannot pay, you still come back.”

Wright stared.

“Why?” he asked.

“Because you are hurt,” Gustav said simply. “That is enough.”

The local medical society suggested, gently, that it might be “easier” if he maintained separate facilities.

He wrote back that he’d taken the Hippocratic Oath, that bacteria didn’t respect color lines, and that if they wanted him to compromise care for prejudice, they’d have to expel him.

They did not.

He suspected they didn’t want the public trouble of removing a well-liked doctor more than they agreed with him.

It didn’t matter.

He ran his practice by his own standard.

Same exam room.

Same instruments.

Same care.

For everyone.

He knew one man couldn’t fix a system.

He’d already spent enough years working in a system that had been evil at its core to know you couldn’t bandage over rot.

But he could refuse to reproduce it in his own small sphere.

That, he’d learned from Captain Bernstein.

9. The Shock That Never Faded

The abundance never stopped startling him.

Grocery stores with aisles of canned goods.

Oranges piled in pyramids in winter.

Meat that people left on plates and sent back to the kitchen.

He would stand in front of the produce section at Piggly Wiggly, staring at bananas like they were museum pieces.

“You all right, Doctor?” the teenage clerk would ask.

“Yes,” he’d say. “I am remembering when there were no oranges.”

The freedom surprised him, too.

The first time he drove his used Ford across state lines without anyone asking for papers or passes, he had to pull over and sit, hands gripping the steering wheel, heart pounding.

He could go anywhere.

No checkpoints.

No guards.

The sky was his border.

Becoming a citizen in 1955 gave that feeling a new shape.

He stood in a row in the courthouse, right hand raised, and swore allegiance in careful English.

A reporter asked him afterward what America meant to him.

“Second chances,” he said finally. “The possibility of becoming something different than what you were born to be.”

He kept the clipping from the next day’s paper in his desk drawer.

10. Guilt and Gratitude

Not everything sat easily.

His sister Maria died of tuberculosis in Bremen in 1953.

Treatable.

But not treated.

Antibiotics had been slow to reach the Soviet zone. Politics controlled medicine there in a way that felt horribly familiar.

He sat in his office, surrounded by shelves of drugs that could have saved her, and felt guilt press down on him like a weight.

Should he have gone back?

Could he have made a difference?

Probably not.

One doctor couldn’t fix a whole country’s shortages, any more than he could have stopped what had been done in the camps.

He sent money to his nieces.

Eventually, he sponsored them to come to America.

They arrived in the 1960s, carrying small suitcases and big eyes, and built their own lives here.

He never made peace with Maria’s death.

He simply folded it into the complicated shape of his existence.

Grateful to America.

Critical of it.

Haunted by Germany.

Unwilling to return.

11. The Long Arc

By the 1970s, his hair was white.

He’d treated three generations of some families.

Delivered babies who now brought in their own children with fevers and scraped knees.

He’d watched the South start to change—slowly, painfully. Brown v. Board. Civil rights marches. The removal of Colored signs from water fountains.

His accent never disappeared completely.

Children in his exam room liked to ask where he was from.

“Here,” he’d say.

“And before that?”

“A place that doesn’t exist anymore,” he’d answer. “Not the way I remember it.”

He got a questionnaire from the German government once, in the ’60s.

Do you feel you fulfilled your duty to Germany? it asked.

He stared at the question for three days.

He thought of field hospitals on the Eastern Front.

Of the boy Müller in the Ardennes.

Of camp hospitals in Mississippi.

Of appendectomies in Georgia.

In the end, he wrote, I fulfilled my duty as a physician. That is the only duty I can answer for.

They never replied.

12. The Last Patient

He died in 1987, in his office, after finishing a morning’s appointments.

Heart attack.

Instant.

The kind of death doctors secretly hope for: quick, painless, between rounds rather than in the middle of one.

His funeral at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church was full.

Soldiers he’d treated in the ’40s and ’50s.

Teachers he’d kept on their feet.

Maids and mechanics and their children.

In the front pew, two women from Bremen—his nieces—cried quietly.

The pastor, whose father Gustav had once treated for pneumonia back in 1949, spoke gently.

“He came to this country as an enemy,” he said. “He stayed as a neighbor. He practiced medicine for forty years in a town that did not have to accept him and owed him nothing. He repaid that indifference with care. In doing so, he showed us that human worth transcends uniform and flag.”

After the service, people swapped stories on the church lawn.

“The German doctor who let me pay with eggs when my Henry was out of work.”

“The one who came to the house at two in the morning when my boy couldn’t breathe.”

“The one who saw my mama in his regular exam room when no one else would.”

No one mentioned the Ardennes.

Camp Clinton.

The ice cream.

Those parts of his life didn’t fit neatly into small talk.

But they were there, in the fact that he existed in this cemetery at all, not as PW 47,312 in some anonymous grave, but as Dr. Yocom with dates on his stone and stories people remembered.

When he’d stood under that shattered oak tree in April 1945, hand on rough bark, morphine gone, enemy engines closing in, the war had offered him two choices: run or stay.

He’d stayed.

Because he was too tired to run.

Because a boy named Müller was bleeding.

Because somewhere under the layers of uniform and ideology, he was still just a doctor.

That choice had led to chains, then to morphine, then to coffee and sugar, then to Mississippi pine forests, then to a bus ticket, then to a small office above a hardware store in Georgia.

He saved Müller’s life that day.

America, in a strange way, saved his.

Not by forgiving him.

Not by pretending the past hadn’t happened.

But by insisting that a standard—of medicine, of treatment, of basic decency—applied even to the hands that had once worn the wrong uniform.

The morphine, the coffee, the ice cream, the trust—they weren’t sentimental gestures.

They were the structure.

It shocked him.

It changed him.

And it left behind a story that refused to resolve into something simple.

Enemy and friend.

Guilt and grace.

Abundance and injustice.

All held together in one life that started in the Ardennes mud and ended in a small Southern town, with patients saying, “Thanks, Doc,” to a man whose first word to his captors had been:

“Help.”

The end.

News

Black Maid Stole the Billionaire’s Money to save his dying daughter, —what he did shocked everyone

By the time the handcuffs clicked shut around her wrists, Clara Briggs had stopped feeling like a person. The metal…

Millionaire Secretly Followed Black Nanny Home After He Fired Her – What He Saw Was Unbelievable

By the time Charles Whitmore realized he’d fired the only person holding his family together, he was sitting in his…

Racist In-law Pours Wine On Black Bride, Unaware Her Father Is A Millionaire

The first glass of wine hit her like an accusation. One splash, then another—thick, red, and deliberate. The music cut…

Millionaire Installed CCTV to catch Black Nanny, But What He Found Out Shock Him

Jack Thompson had spent his whole life building walls. Not the kind made of brick and stone—the kind made of…

A beggar was thrown out of the car dealership, not knowing he was the undercover owner!

Alex Mercer built his empire on control. Numbers, projections, margins—those were things he understood. Nothing in his dealerships happened by…

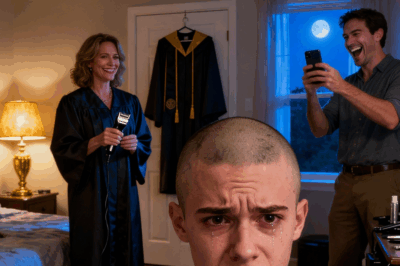

The night before my graduation — the day I worked four years to reach — my mom stormed into my room with clippers in her hand. With a cruel smile, she shaved my head bald, mocking me, “Bald like your future.” My dad stood beside her, laughing, snapping pictures as if it were the funniest family joke. But what they didn’t know was that this humiliation would not break me. It would become the fire that

The night before what should have been the proudest day of my life, I sat on my bed, carefully running…

End of content

No more pages to load