Part 1 – The Hole in the Line

December 16, 1944

Ardennes Forest, Belgium

Private Joe Miller woke up thinking the war might actually be over before spring.

He lay in his foxhole with his boots on, wrapped in a damp wool blanket, breath steaming in the frozen air. The woods around him were quiet—too quiet for Europe in 1944. No artillery, no distant tank engines, just the muffled stillness of snow on pine branches.

“Hey, Miller,” Corporal DeLuca muttered from the next hole over. “You asleep or freezing to death over there?”

“Bit of both,” Joe croaked. “You hear anything?”

“Yeah,” DeLuca said. “I hear a whole lot of nothing. Maybe the Krauts finally ran out of hate.”

They both knew the line in front of them was supposed to be quiet. The Ardennes sector was “a rest area,” command had said. A place for worn-out divisions to catch their breath, heal up, and take in replacements before the next push into Germany.

Joe had believed it for maybe twenty minutes.

It was still dark when the first shells came in.

The forest ripped open with noise.

Artillery—heavy stuff—pounded the thin American positions, trees exploding in bursts of wood and shrapnel. Joe rolled onto his face as a shell landed close enough to dump half a foxhole of snow and dirt on his back.

“What the hell?” he shouted.

“The hell is here!” DeLuca yelled back.

The bombardment lasted minutes that felt like hours. Then, through the ringing in his ears, Joe heard something else:

Engines. Many, many engines.

“Germans!” someone screamed down the line.

Joe grabbed his M1, scrambled up just enough to peek over the lip of his hole.

Shadows moved between the trees—figures in white smocks over gray uniforms, some on foot, others riding on the backs of tanks that seemed to materialize out of the mist. The pines flashed in the muzzle bursts of German machine guns. A half-track roared past a break in the line, its crew firing wildly.

The “quiet sector” had just become the center of hell.

Forty miles to the west, in Luxembourg, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Carter was yanked out of a warm cot by a telephone that sounded like it hated him personally.

He grabbed the receiver, blinking sleep out of his eyes.

“Carter,” he said.

“Jim, it’s Harding,” came the voice of his operations counterpart. “Get to the ops tent. Now. The Krauts just knocked on the First Army’s front door with an axe.”

Jim took ten seconds to splash water on his face, jammed his feet into boots, and pulled on his field jacket. The December air cut through the canvas walls as soon as he stepped outside. Snow crunched under his soles.

Third Army headquarters was a cluster of tents and semi-permanent huts, camouflage netting draped over trucks and generators. Inside the ops tent, a big map of the Western Front dominated one wall.

It looked different today.

Someone had dragged a thick red pencil across the American line in the Ardennes and pushed it back twenty miles.

“What the hell is that?” Jim asked, pointing.

“New front line as of about five minutes ago,” Harding said, dark circles under his eyes. “German offensive. Big. They hit the VIII Corps sector with everything from infantry to Panthers. Reports are all messed up—units overrun, communications cut—but it’s not a raid. It’s an operation.”

Jim stared.

“The Ardennes?” he said. “That’s supposed to be… quiet.”

“Tell that to the two hundred fifty thousand Germans,” Harding said. “Intel’s guessing twenty-nine divisions. Maybe a thousand tanks.”

“Jesus.”

“We got orders,” Harding went on. “General Patton’s called for a full situation conference at Verdun. Eisenhower’s gonna be there. Bradley. The whole circus. You’re coming with the general’s staff group.”

Jim blinked.

“Verdun,” he said. “Like, as in Verdun Verdun?”

“Yeah,” Harding said. “Apparently, we’re about to see if history repeats itself.”

Metz, France

Same morning

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr. finished buckling his pearl-handled revolver and looked at himself in the mirror.

The face looking back at him was sixty-ish, deeply lined, the eyes pale and hard. The helmet he’d made famous—olive drab with three stars—sat on a nearby chair. The uniform, freshly pressed as always, looked like it had been painted on.

“Cold as a witch’s tit,” he muttered, picking up his winter overcoat. “Perfect weather for killing Germans.”

His aide-de-camp, Colonel Codman, appeared in the doorway.

“Sir, the car’s ready,” Codman said. “Eisenhower wants you at Verdun as soon as possible. They say the Germans have launched something big in the Ardennes.”

“They’ve launched something stupid,” Patton said, shrugging into the coat. “They’ve stuck their head out when they should have kept it tucked under a rock. Now we’re going to break their neck.”

He picked up his helmet and tucked it under one arm.

“Told you months ago they’d try something like this,” he added. “Too damn quiet in that sector. The Germans may be bastards, but they’re not lazy bastards.”

Codman held the tent flap aside as they stepped into the cold.

Snowflakes drifted in the air, fine as dust. Trucks idled nearby, their exhaust ghosting into the gray sky. Somewhere, a generator hummed.

Patton paused to look out over the Third Army’s area.

They were already heavily engaged—pushing through the Saar, battering at Metz and the approaches to Germany’s industrial heart. Supply had been tight. Fuel, ammunition, winter clothes had all had priority arguments.

Now the Germans were lunging out of the Ardennes toward Antwerp in what they clearly hoped would be a war-changing blow.

Patton’s brain ticked through the map in his head—First Army to the north, Third Army to the south, the line bending inward where the attack had punched through.

“They want Antwerp,” he said quietly. “They want to split us and the British, maybe take the port, maybe force Ike to think about negotiating. They’re idiots.”

Codman looked at him.

“They’re using what they’ve got left,” Patton said. “Tanks and boys. And they’ve only got so much fuel. They run six days at most before they have to start stealing gas from us. You don’t win a war on stolen gasoline.”

He walked toward the waiting staff car, boots crunching. His mind was already three moves ahead.

He’d had his G-2, his intelligence officer, watching the Germans for weeks. Reports of increased movement. Odd radio silence. Shadows where there should have been noise. He’d ordered contingency plans drawn up—fantasy football for generals, some of his staff had joked.

Except now the fantasy was about to be real.

“Verdun,” Patton said as he climbed into the car. “They’re going to wring their hands and talk about ‘stabilizing the line.’”

He snapped his helmet on, chinstrap tight.

“We’re going to talk about hitting them in the guts.”

December 19, 1944

Verdun, France

The officers gathered at Verdun wore more stars on their shoulders than some constellations.

Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower sat at the head of the table, expression calm but tight. Beside him, Omar Bradley, commander of 12th Army Group, rubbed his face with a tired hand. Around them were corps and army commanders, their staffs, intelligence officers, logistics men.

On the wall, a huge map of Belgium and Luxembourg showed a brutal, unmistakable shape.

The American front line, which had been a relatively straight line running roughly north-south, now bulged westward in a fat wedge.

The Ardennes.

“Gentlemen,” Eisenhower said, tapping the map with a pointer, “the Germans have punched a hole in our line here. The press will undoubtedly have a field day with the shape. We’re already hearing from London they’re calling it ‘the Bulge.’”

A few tight smiles.

“The reality is,” Ike went on, “they’ve driven about twenty miles into our positions in three days. They’ve encircled Bastogne. They’re aiming for the Meuse and ultimately Antwerp. They’ve achieved tactical surprise. Our intelligence missed their buildup entirely.”

The silence in the room was heavy. No one looked at the G-2 guys.

“They’ve thrown in around two hundred fifty thousand men and a thousand tanks,” Eisenhower said. “That’s a lot of weight. But it’s also most of their remaining strategic reserves in the West. If they fail, they won’t have much left to stop our spring offensive.”

Bradley leaned forward.

“First Army’s in chaos,” he said. “Hodges has units cut off, others retreating. Communications are a mess. Bastogne is holding for now, thanks to the 101st, but if the Germans get armor past them, they could reach the Meuse in a couple days.”

He looked around the table.

“We need to stop them,” he said simply. “Fast. And then turn this into a disaster for them.”

Eisenhower nodded.

“Montgomery is shifting forces from the north,” he said. “From the south…” He turned to Patton.

“George,” Ike said, “how long will it take you to shift your Third Army north to attack into the southern flank of this thing?”

Everyone in the room turned to look at Patton.

This was the moment Jim Carter would remember for the rest of his life.

He sat behind the Third Army staff section, a notepad in front of him, pencil poised. He’d expected Patton to say something like, “Give me a week,” or “We need ten days to redeploy.”

Instead, Patton reached into his pocket, pulled out a cigar, and rolled it between his fingers, eyes on the map.

He spoke in that high, surprisingly thin voice of his.

“I can attack with three divisions in forty-eight hours,” he said.

It was like someone had dropped a plate.

Generals who’d been in the business for decades stared at him.

Eisenhower blinked.

“Forty-eight hours?” he repeated. “George, you’re already engaged against the Saar. You’re in contact with the enemy. You’d have to pull divisions out of line, turn them ninety degrees, and march a hundred miles in winter.”

“Seventy-two hours if you want it pretty,” Patton said. “Forty-eight if you don’t mind a little mess. But we’ve already done the planning.”

Jim watched Ike’s eyebrows rise.

“Already?” Eisenhower asked.

Patton nodded.

“My G-2 spotted German movement a while back,” he said. “Could’ve been nothing, could’ve been this. I had my staff draw up three contingency plans—one for turning north to hit near Bastogne, one farther east, one farther west. Soon as you called this meeting, I told them to prep the Bastogne option. All I needed was your say-so.”

He leaned forward, eyes bright.

“Let the sons of bitches drive west,” he said. “The farther they go, the more their flanks stretch and their gas runs out. We hit the base of the bulge, relieve Bastogne, and we don’t just stop them—we cut them off.”

He stabbed a finger at the map where the German arrows plunged west.

“This is their last throw,” he said. “They’ve got maybe six days of fuel. They’re counting on the weather to keep our air grounded and on us to sit here wringing our hands. We don’t. We attack. Always attack. That’s how you fix a problem like this.”

Bradley looked skeptical.

“George,” he said, “turning six divisions ninety degrees while under fire is one of the most difficult maneuvers in the book. You’ll be moving on icy roads, in a blizzard, with supply already strained. Every manual we’ve ever read says you don’t do that unless you absolutely have to.”

Patton gave him a thin smile.

“Well, Brad,” he said, “I’d say this qualifies as ‘absolutely have to.’ And manuals are written by the kind of people who sit in warm rooms, not the ones who win wars.”

Eisenhower glanced at Bradley, then back at Patton.

“Can you really do it in forty-eight hours?” Ike asked.

Patton’s gaze was steady.

“ On my honor,” he said. “We can be hitting them in the flank by the twenty-second.”

Silence. Snow tapped faintly at the windows.

Jim felt like he was watching a coin flip that would decide whether thousands of men lived or died.

Eisenhower made his decision.

“All right, George,” he said. “You’ve got the job. Pivot your Third Army north. Relieve Bastogne. Hit their base. Monty will handle the north. We’ll pinch this bulge off like a bad boil.”

He looked around the room.

“Gentlemen,” Ike said, “the present situation is to be regarded as an opportunity, not a disaster.”

Later, Jim would think that was as good a one-line summary of Patton’s entire philosophy as any: turn disasters into chances.

“Any questions?” Eisenhower asked.

No one had any.

The meeting broke up into smaller clusters of hurried conversations. Orders would be drafted, radios buzzing, staffers bent over typewriters.

Patton walked toward the door with his staff.

In the hallway, Jim hurried to catch up.

“Sir,” he said, “did you mean it? Forty-eight hours?”

Patton didn’t slow down.

“Hell yes, I meant it,” he said. “We’ve already done the hard part—the thinking. Now we just have to move a quarter of a million men and their tanks through an ice storm.”

He grinned, a flash of teeth in his lined face.

“Piece of cake.”

As soon as they were in the car, Patton grabbed the field telephone handset bolted to the dashboard. The driver cranked the engine; the car lurched down the cobbled street.

“Get me Third Army headquarters,” Patton barked into the phone.

Static. Then a clipped voice: “Third Army HQ, this is Major Harding.”

“Harding, this is Patton,” the general said. “Play ball.”

Two words.

Jim felt the hairs on his arms prickle.

They were the prearranged code—agreed upon days before, in a quiet tent while snow tapped the canvas. If those words came down the wire, every staff officer back at Third Army knew exactly which paperwork to pull out of which drawer.

“Yessir,” Harding said. “Play ball. Understood.”

He didn’t ask for clarification. He didn’t need to.

Within minutes, staff officers at Third Army HQ were tearing open envelopes stamped with contingency labels. Operation plans for a ninety-degree pivot.

Orders for the Fourth Armored Division, the 26th Infantry Division, the 80th and 35th, and others began to spool out of typewriters. Motor pools were told to prepare convoys. Artillery units were given new firing positions. Supply officers were told to move heaven, earth, and 62,000 tons of fuel and ammunition north.

On paper, it looked impossible.

Six divisions, 133,000 vehicles, ordered to disengage from active combat, turn on frozen roads in the dead of winter, and march over a hundred miles to hit a battle they were not currently in.

On paper, it was madness.

Patton had never liked paper much.

“You see, Jim,” he said to Carter in the back seat as they rattled south, “you don’t wait for the enemy to finish his idea before you start yours. Hitler’s plan requires time—time to push to the Meuse, time to grab our fuel dumps, time to get to Antwerp. It requires the weather to stay bad. It requires us to be stupid.”

He snorted.

“I may be crazy,” he said, “but I’m not stupid.”

Jim managed a weak smile.

“Sir, this is still…” he searched for a word that sounded professional and not terrified, “…ambitious.”

Patton laughed.

“Ambitious? Hell, son, that’s what generals are for,” he said. “If all you want is a man to shuffle units on a map according to the manual, you don’t need me. They didn’t drag me out of mothballs after Sicily to play it safe.”

He looked out the window, jaw tightening.

“This is what I’ve been training for since I was knee high,” he said quietly. “Since I read Caesar and Napoleon at my mama’s table. Since I rode a damn tank in France in 1918. Destiny has a habit of showing up in the ugliest wrapping paper.”

Snowflakes streaked across the car’s windshield, thicker now.

Up ahead, Third Army convoys would soon be grinding north, engines revving against the cold, drivers hunched in greatcoats, infantry riding in open trucks with blankets pulled up around their faces.

In the Ardennes, Private Joe Miller would be digging his foxhole deeper, wondering if anyone out there knew he existed.

He had no idea that a man who talked loudly about destiny had just told a quarter of a million Americans to start walking his way.

Bastogne

December 20, 1944

Joe Miller’s world had shrunk to the size of a town he’d never heard of before two days ago.

Bastogne.

He’d fallen back with what was left of his unit under orders, retreat turning into a fighting withdrawal, fighting withdrawal turning into something that felt a whole lot like running. They’d been folded into the 101st Airborne Division’s perimeter, told to dig in, and then the Germans had closed the circle.

Snow drifted in the streets between brick houses. Wrecked vehicles burned low at intersections. The church steeple had a shell hole in it the size of a truck.

“Looks like we’re surrounded,” DeLuca said, leaning on his rifle behind a sandbagged roadblock.

“Good,” Joe said, teeth chattering. “We can shoot in any direction we like.”

It was an old joke by then. A way to cover the fear.

Rumors spread through the frozen foxholes and ruined houses.

The Germans had demanded surrender.

Some general—McAuliffe, the airborne guys said—had written back one word: “NUTS.”

Joe liked that. It felt appropriately American for telling the Wehrmacht to go to hell.

Still, when he looked out at the snow-covered fields, he couldn’t help but wonder how long an island could resist when the tide was all enemy.

He stared at the low clouds.

“Could really use some armor,” he muttered. “Or some air power. Or both.”

Somewhere south of him, an exhausted driver in a Third Army truck ground his teeth as his vehicle lurched over a frozen rut, heading north.

In a jeep up ahead, George Patton stood in the front seat, hands on the windshield frame, his scarf whipping in the wind, his voice carrying over the engine noise.

He shouted at passing columns, at tank crews hunkered in turrets, at infantrymen riding on the backs of armored vehicles.

“We’re going to Bastogne, boys!” he yelled. “We’re going to save those poor bastards and then shove this bulge down Hitler’s throat! This is our finest hour!”

Word spread from truck to truck, from tank to tank, from foxhole to foxhole.

“The old man says we’re the finest soldiers in the world.”

“Georgie says this is our finest hour.”

Private Joe Miller didn’t hear those words yet. Not directly.

But he would feel them, soon enough, in the thunder coming up from the south.

Part 2 – Play Ball in a Blizzard

December 20–21, 1944

On the road north with Third Army

You couldn’t really call them roads.

Sergeant Ray Jackson decided they were more like suggestions.

He hunched over the wheel of his deuce-and-a-half truck, eyes narrowed at the barely visible strip of white ahead. Snow whipped sideways, slamming against the windshield. The wipers squeaked a miserable rhythm.

“Can’t see a damn thing,” his assistant driver, PFC Morales, muttered, blowing into his gloved hands.

“You can see the taillights, can’t you?” Jackson asked.

A pair of dim red glows bobbed in the snowstorm ahead—the back end of the truck in front of them.

“Yeah.”

“Then quit complaining,” Jackson said. “You lose those lights, we’re lost. You wanna spend Christmas in a ditch in Luxembourg?”

The convoy stretched for miles—trucks, half-tracks, tanks on trailers, jeeps darting in and out like impatient terriers. Men rode in the backs of vehicles wrapped in blankets, helmets pulled low, rifles cradled. Every now and then, a man pounded on the truck bed to wake up a buddy who’d slumped too far toward the edge of hypothermia.

Orders had come down fast.

One day they’d been shelling German positions on the Saar. The next, they were told to pack, gas up, and head north. No explanations beyond the basics: the Krauts had broken through in the Ardennes, and Bastogne was in trouble.

“Third Army’s turning north, boys,” an officer had shouted. “We’re gonna hit the bastards from the side. We move now.”

Now never looked so cold.

“Hey, Sarge,” Morales said, squinting through the windshield. “You really think Patton’s up there? Riding around in an open jeep like they say?”

Jackson snorted.

“I saw him yesterday near the start line,” he said. “Standing up in that jeep like he thought he was bulletproof. No top, just that big damn overcoat and a scarf. Saluted a bunch of us convoy rats like we were cavalry on parade.”

He adjusted his grip on the wheel as the truck hit a patch of ice and skidded, tires squealing. He eased off the gas, corrected, and got them back in line.

“What’d he say?” Morales asked.

“Said, ‘We’re going to save Bastogne, boys! Let’s show these bastards Americans don’t know how to retreat!’” Jackson replied. “Then he told us to stay off the damn brakes.”

Morales laughed in disbelief.

“Crazy old man,” he said.

“Yeah,” Jackson agreed. “But he’s our crazy old man.”

The radio in the cab crackled with occasional bursts from convoy control, voices distorted by static and bad weather.

“Red Dog Five, maintain spacing… Blue Column, watch for ice on the next grade… Engineers report bridge intact at grid…”

It was organized chaos.

They had to keep moving and stay hidden at the same time.

Lights were blacked out or covered. Engines had to be kept running or started every thirty minutes lest the oil turn to sludge. Men grabbed sleep in ten-minute shifts, curled up against each other for warmth. Machine gunners wiped frost off their barrels every hour.

Somewhere in the mass, Jim Carter sat in a bouncing command car, maps spread on his knees, pencil darting as reports came in.

“Fourth Armored is making good time,” his radio operator said, one ear glued to the handset. “Twenty-sixth Infantry’s column is slowed by a jackknifed truck, but engineers are on it.”

Jim scribbled notes.

He remembered something one of the staff wargamers back in the States had said once: “The most difficult maneuver in warfare is a pivot on contact.” Meaning: trying to swing an army in a new direction while already in a fight.

They weren’t just pivoting. They were doing it in a blizzard.

“Sir,” the driver said, peering ahead, “you ever read the manuals on this move?”

Jim nodded.

“They all say, ‘Don’t,’” he said.

The driver grinned.

“Guess it’s a good thing the old man doesn’t read manuals.”

Jim thought of Patton in Verdun, saying “forty-eight hours” like it was an item on a grocery list.

He’d seen generals bluff before—soft deadlines, best-case estimates spoken aloud in hope rather than certainty.

Patton had sounded like a man reciting a schedule he’d already committed to memory.

Jim looked out the window at the endless line of vehicles.

The schedule was now made of cold metal and exhausted men.

German Seventh Army HQ

Same time

General Erich Brandenberger stubbed out his cigarette and leaned over the map table.

The red arrows thrusting west from the German lines looked beautiful on paper.

Their armored spearheads had driven miles into the American positions in just days. Towns with names his staff had barely heard of a week ago were now occupied—Clervaux, St. Vith. Columns of American prisoners had marched east through the snow, guarded by German NCOs who snorted at their thick coats and cigarettes.

Hitler’s “Watch on the Rhine” had opened with a bang.

But Brandenberger was old enough to know the danger hidden in pretty arrows.

“How are our fuel stocks?” he asked, not looking up.

Oberstleutnant Hahn, his logistics officer, cleared his throat.

“Low, Herr General,” he said. “We started the offensive with barely enough for six days of full operations. We’re already cannibalizing damaged vehicles, siphoning from anyone not on the spearhead. The plan assumes we capture Allied fuel dumps near the Meuse by the fourth or fifth day.”

“And the Allied reaction?” Brandenberger pressed.

Hahn glanced at another officer.

“We expected some counterattack from the south,” the intelligence major said. “But their activity there has been… limited. Some shifting patrols. No sign yet of large-scale movement.”

Brandenberger frowned.

He had studied Patton. All good German officers had.

While they had mocked American generals like Mark Clark as political, and British ones as plodding, Patton had worried them. His hurry, his flexibility—those were traits they recognized and feared.

“He will react,” Brandenberger murmured. “Patton does not sit still. He is closest to our flank. He uses armor like we do—fast, concentrated. But… in this weather…”

He let the thought trail off.

Winter.

It had been both ally and enemy to German arms.

In Russia, in ‘41 and ‘42, they had seen how cold could paralyze engines, freeze oil, break weapons. They remembered men’s feet turning black and falling off. They remembered entire divisions halting because the thermometer dropped.

The Americans? They had never fought a winter like that. Their supply columns were fat, their soldiers known for complaining if they didn’t have hot coffee every morning. German officers joked that if you took away their cigarettes and warm socks, the Americans would crumble.

Brandenberger knew they underestimated the Americans in other ways. He’d seen how quickly they’d learned since North Africa, how their artillery coordination had improved, how their air power had turned roads in France into deathtraps.

Still.

Moving an entire army in December, in this region, over icy roads?

Even he found it hard to imagine.

“We’ll watch them,” he said finally. “But I expect the weather and their own comforts will keep them pinned.”

He turned his attention back to the big red arrow.

He didn’t see the pencil-thin line of green moving north on another man’s map.

December 21, 1944

Third Army HQ

“Christ, it’s like herding cats,” Harding groaned, rubbing his temples.

Telephones rang incessantly. Radio operators shouted into microphones, wrestled with static. Orderlies hustled sheets of paper from one desk to another. The big map of the region was covered in colored pins—blue for American units, red for German, green for movements underway.

Jim Carter slid in beside Harding, a steaming mug of coffee in hand.

“That for me?” Harding asked.

“Nope,” Jim said, taking a sip. “You look like you’ll die quicker if we caffeinate you.”

Harding smirked.

“Columns Alpha through Charlie are on schedule,” he said, nodding at the map. “Delta’s been delayed by a blown bridge, but engineers are halfway through a Bailey.”

“And the old man?” Jim asked.

“Where else?” Harding nodded toward the open tent flap.

Outside, Patton’s jeep idled, exhaust puffing. The general stood in the snow, talking to a group of division commanders like they were a football team in a huddle.

“…I don’t give a damn about the weather,” Patton was saying, voice carrying. “The Kraut thinks it’s his friend. He thinks the fog keeps our planes grounded and our asses frozen. That’s his mistake. Winter doesn’t stop Third Army, it slows Third Army. And we don’t even like being slowed.”

He looked from face to face.

“You will hit on the twenty-second, gentlemen,” he said. “Not the twenty-third, not Christmas Eve. The twenty-second. The Bastogne boys are holding by their fingernails. They’re airborne—they’re tough—but they’re human. We relieve them, we stabilize this thing, and then we turn this bulge into a noose.”

One of the division commanders, General Dager of Fourth Armored, frowned.

“Sir, my lead elements are still strung out,” he said. “Traffic, ice, breakdowns. If we push too hard, we risk hitting their lines piecemeal.”

Patton nodded.

“Valid concern,” he said. “Mitigated by the fact that if we don’t push too hard, the bastards in Bastogne will be dead or prisoners before you ever get there. I’ll take a calculated risk over a guaranteed loss any day.”

He slapped Dager’s shoulder.

“You’ve got the best armored division in Europe,” Patton said. “Prove it.”

He turned to his corps commander.

“Corkins, your infantry will follow the armor,” he said. “The roads are narrow. You hug those Shermans’ asses like you’re married to them. No gaps. No dawdling. If a truck breaks down, you push it off the road and keep going. I don’t want to hear about a single goddamn traffic jam.”

“Yes, sir,” came the chorus.

“Good,” Patton said. “Now get the hell out of my headquarters and go kill Germans.”

They dispersed, heading for their vehicles, aides hurrying after them.

Patton watched them go, then looked up at the low, unbroken clouds overhead.

He chewed on his cigar.

“Be nice if you’d give me a little sunshine, Lord,” he muttered. “Never thought I’d have to ask.”

He had already done more than mutter.

Two days earlier, he’d summoned his chaplain, Colonel James Hugh O’Neill, into his tent.

“I want you to write me a weather prayer,” Patton had said.

O’Neill had blinked.

“A… prayer for the weather, sir?” he’d asked.

“Yes,” Patton said. “For good weather. For killing weather. I want clear skies so my flyboys can get up and pave the way.”

O’Neill had hesitated.

“Begging the Almighty to change meteorological conditions may be… slightly presumptuous, sir,” he said.

Patton had glared.

“Chaplain,” he said, “I am a third army commander asking for His help. That’s your business. Write the damn prayer.”

O’Neill had written it.

“Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle…”

Patton had ordered 250,000 copies printed and distributed to every man in Third Army, along with a Christmas greeting.

Some laughed. Some folded it into their wallets. Some read it and actually prayed.

Patton, for all his profanity and swagger, took it dead serious.

“Between God, my tanks, and the Air Corps,” he’d told Codman, “we’ll make mince meat out of this Bulge.”

December 22, 1944

South of Bastogne

Private Joe Miller had learned to read battles by sound.

You couldn’t always see the front line, not with the hedgerows and woods and broken ground. But you could tell a lot from the noise.

German artillery had a weird crack-thump. American howitzers had their own signature. Small arms, mortars, the occasional tank gun—all spoke in a language of explosions.

For days, the dominant voice had been German.

Shells had crashed into Bastogne from almost every direction. Screaming meemies, Nebelwerfers, had filled the night with howling rockets. Panzer engines had growled outside the perimeter, trying to probe for weak spots.

The 101st Airborne and the attached units, including Joe’s battered battalion, had held. Barely.

Now, huddled in a snowed-in foxhole on the southern edge of town, Joe heard something new.

Distant thunder. Many engines. Coming from the south.

“DeLuca,” Joe said, elbowing his foxhole buddy. “You hear that?”

DeLuca cocked his head.

“Artillery?” he asked.

“No,” Joe said slowly. “Sounds like… trucks. Tanks. A lot of ‘em.”

DeLuca’s eyes widened.

“You think…?”

“I think maybe someone heard we’re having a party,” Joe said.

He didn’t want to get his hopes up. He’d already watched a couple of what he’d thought were relief attempts die under German shelling. The Krauts had ringed the town good.

But the sound grew, a low rumble washed and warped by the cold air. Every now and then, a different note cut through—higher pitched, like a tank’s engine revving hard.

“Hey!” someone shouted down the line. “Hear that? Armor!”

“Probably more Krauts,” another voice muttered grimly.

Then, faint but distinct, over the wind and the vehicles, came another sound:

American artillery firing in support. The whistle of shells passing overhead—from the south.

Joe clutched his rifle a little tighter.

“C’mon,” he whispered. “Come on, you Third Army boys. Get here before we’re popsicles.”

December 22, 1944

Third Army Attack

The Fourth Armored Division led the way.

Lieutenant Charles “Chuck” Boggs—Bogus to his men, after a clerk had misspelled his name once and it stuck—stood half out of his Sherman’s turret, goggles on, scarf whipping. Snow pelted his face.

He looked over his shoulder at the line of tanks following him, hull-down behind low ridges, their guns pointing forward like a row of accusing fingers.

Ahead, across a flat, white field broken only by fence lines and the occasional tree, lay the German positions—foxholes, dug-in anti-tank guns, scattered buildings.

His radio crackled.

“Red One, this is Red Six,” came the battalion commander’s voice. “You’re go, Bogus. Patton wants Bastogne. Let’s give him his damn Christmas present.”

Boggs grinned.

“Red Six, Red One,” he said. “Moving.”

He dropped back into the turret and slapped the loader on the shoulder.

“Gun loaded?” he asked.

“AP up!” the loader shouted over the engine noise.

“Driver!” Boggs yelled. “Forward! Let’s give these Krauts a taste of Detroit!”

The Sherman lurched, treads chewing through snow. The formation moved with it, tank after tank cresting the slight rise.

German machine guns opened up first, tracers stitching the snow. The rounds pinged off the Shermans’ frontal armor, leaving bright scars.

Then the German anti-tank guns spoke—sharp, deadly cracks.

AP rounds slammed into the lead American tanks. One Sherman to Boggs’s left shuddered as a round punched through its lower front plate. Flames burst from its hatches. Men scrambled out, some on fire, others dragging the wounded.

Boggs swallowed hard.

He’d trained for this. North Africa, Normandy. He knew the drill.

“On that gun!” he shouted, spotting a muzzle flash on the edge of a farmhouse. “Traverse left… steady… fire!”

The Sherman’s 75mm barked. The recoil slammed through the turret.

The shell hit the farmhouse corner, blowing bricks and wood in all directions. The anti-tank gun vanished in a shower of debris.

The field became a churning nightmare of explosions, smoke, and snow. Tank rounds, artillery, machine-gun bursts. Infantry crawled behind the tanks, using their hulks as moving cover, then peeling off to clear trenches and houses.

From above, the battle would have looked like a knot of ants fighting on a white tablecloth.

From inside a tank, it felt like the universe had shrunk to the thickness of armor plate and the distance to the next hedgerow.

In the midst of it all, Patton’s orders rippled down the chain:

“No stopping. No hesitation. You push until you link up with the 101st.”

At Third Army HQ, Jim Carter listened to the crackling reports.

“Fourth Armored has pushed seven miles on the first day, sir,” Harding said. “They’re past Martelange. Heavy resistance, but they’re still moving.”

Patton nodded, face grim.

“The Germans didn’t think we’d attack in this weather,” he said. “They counted on the cold to do their work. They forgot Third Army’s got thicker blood.”

He looked at the cloudy sky again.

“Still waiting on your contribution, Lord,” he muttered.

December 23, 1944

The prayer and the sky

The twenty-second had been all steel and snow.

The twenty-third brought something else.

It started as a thinning—a subtle lightening behind the low gray clouds. Men on both sides looked up from their foxholes, squinting.

Around midday, the clouds broke.

Blue showed through, sharp as enamel. Sunlight glared off the snow, forcing squinting and hastily donned goggles.

In Third Army HQ, a meteorology officer ran into the operations tent, face flushed.

“Sir!” he shouted. “Weather’s clearing across the sector. The ceiling’s lifting. Visibility’s improving fast.”

Patton’s head snapped up.

“How fast?” he demanded.

“Fast enough to fly,” the officer said, almost grinning.

Patton’s eyes gleamed.

“Get me Air,” he barked. “Right now.”

Within hours, the drone of engines filled the sky.

P-47 Thunderbolts and P-38 Lightnings, drab olive and gleaming silver, swept in low over the Ardennes. C-47 transport planes formed long strings, towing gliders and parachute canisters toward Bastogne and other pockets.

Over German positions, the fighter-bombers went to work.

They dove on columns of trucks, tanks, and horse-drawn wagons. Rockets flared from their wings, streaking down. Bombs tumbled, fins whistling.

On a snow-covered road, a German fuel convoy went up in a chain of fireballs. Men dove into ditches, boots kicking up white powder.

A young German lieutenant pressed himself into a roadside hollow as a P-47 flashed overhead, its eight .50-caliber machine guns chewing up the column.

“We cannot move!” he shouted to his sergeant. “The Americans own the sky again!”

His sergeant didn’t answer. He was staring at the burning trucks, eyes hollow.

In Bastogne, Joe Miller heard a new sound—American planes, low and loud.

He staggered out from behind a house and looked up.

C-47s flew over in tight formations, dropping parachute canisters. White, red, and green chutes blossomed against the blue. Boxes slammed into the snow outside town.

“Supplies!” someone yelled. “They’re dropping supplies!”

Joe laughed, a wild, relieved sound.

“Look at that,” DeLuca said, grinning. “Sky’s rainin’ presents.”

Over the radio, messages zipped back and forth.

“Third Army, this is IX Tactical Air Command. We’ve got fighter-bombers in your sector. Mark your front lines clearly. We’ll keep their roads a mess.”

“Copy, IX TAC. Give ‘em hell. Patton says thanks for the sunshine.”

At HQ, Patton accepted a copy of the chaplain’s prayer, now smudged and folded from passing through many hands.

“Looks like you came through, Father,” he said quietly.

O’Neill shrugged modestly.

“The men’s faith, sir,” he said. “And perhaps a bit of meteorology.”

Patton snorted.

“Hell with that,” he said. “I’m putting you in for a medal for best damn weather forecast in the army.”

He tucked the prayer into his pocket.

Later, in his diary, he wrote, “This clear weather came just in time. This, combined with the Third Army’s pivot, saved the situation.”

It didn’t sound very bombastic.

The men in foxholes felt it as an answered need, not a neat sentence.

December 24–25, 1944

Into the meat grinder

Christmas Eve in the Ardennes looked nothing like the cards back home.

The snow was there, yes. The trees. The little villages with churches.

But the snow was churned up and stained. The trees were shattered. The churches had shell holes for stained glass.

Third Army’s attack had burned through the initial German surprise. Now the Germans were reacting hard.

Panzer units that had been looking westward at the Meuse suddenly had to swing south, facing a new threat from Patton’s columns.

The fighting around places like Bigonville, Chaumont, and Assenois turned into a meat grinder.

Boggs’s tank battalion lost Shermans by the dozen.

Panthers and Tigers rolled into view, their 75mm and 88mm guns lethal at long range. Shermans tried to close the distance, using speed and numbers.

In one engagement, Boggs watched a Tiger sit at the edge of a wood line and knock out three Shermans in ten minutes.

“Damn cat’s playing whack-a-mole,” his gunner muttered.

“Call in the flyboys,” Boggs snapped. “Get that son of a bitch some rockets for Christmas.”

Minutes later, P-47s screamed down, rockets flaring. One pair struck close enough to flip the Tiger like a toy, turret askew.

On the ground, infantry slogged forward through knee-deep snow. Frostbite nipped toes and fingers. Medics worked with bare hands, fingers going numb as they bandaged wounds and jabbed morphine.

At night, the temperature dropped further. Men huddled three to a foxhole, pressed together for warmth, cursing each other’s smell and grateful for each other’s heat.

In one lull, on Christmas Eve, Joe Miller sat in a half-collapsed cellar in Bastogne, eating a piece of chocolate that had been in a dropped supply canister.

“Christmas in Belgium,” DeLuca said dryly. “Not exactly how I pictured it.”

“How’d you picture it?” Joe asked.

“Brooklyn. A bar on Flatbush. My ma yelling ‘eat, Tony, you’re skin and bones’ while she hands me a plate big enough to feed an army,” DeLuca said. “You?”

“Indiana,” Joe said. “Snow. Church. My old man pretending he doesn’t like the carols and singing them anyway.”

DeLuca took another bite, chewed.

“You think they know what’s going on?” he asked. “Back home?”

Joe nodded slowly.

“I think they know something,” he said. “They always know something. They just don’t know what it looks like.”

He thought of letters describing “our boys fighting bravely in Europe,” and wondered how you said “pissing ice in a foxhole while mortar rounds walk up the street toward you” in polite terms.

Outside town, under the same leaden sky, German soldiers shared their own harsh Christmas.

Private Karl Richter, a nineteen-year-old from Cologne, huddled in a forest foxhole with two other men, hands wrapped around a tin cup of weak ersatz coffee.

His boots were worn, socks damp. His stomach growled. His officer had promised that “this offensive will bring us to Antwerp and force the Americans to peace.”

So far, it had brought Karl to a frozen forest facing Americans who refused to break.

“Did you hear what the American general said?” one of his foxhole mates asked. “The one coming from the south?”

“What?”

“He said we stuck our head in a meat grinder,” the man said. “And that he has his hand on the handle.”

Karl snorted.

“That’s what they always say,” he muttered. “We’re the ones grinding them down. We always have.”

But even as he spoke, he heard the distant rumble of tanks to the south, and above, the distant drone of planes.

He sipped his coffee and tried to believe.

December 26, 1944

The corridor

On the morning of the twenty-sixth, the field south of Bastogne looked like a painting someone had slashed with knives.

Trees were broken, fences flattened. Shell holes pocked the snow. Burned-out vehicles dotted the horizon.

Fourth Armored’s 37th Tank Battalion had been pushing for days.

Every time they thought Bastogne was within reach, another German roadblock appeared—a few anti-tank guns here, a clutch of infantry there, a tank or two lurking.

Now, Boggs’s lead tank sat hull-down behind a low rise.

Beyond that rise, in the shallow valley ahead, lay the last German-held stretch between his unit and the 101st Airborne’s perimeter.

Map said the town ahead was called Assenois.

To Boggs, it was just one more grid square.

“Red One, this is Red Six,” came the radio. “You’re almost there, Chuck. Punch through and don’t let go.”

Boggs keyed his mic.

“Roger, Six,” he said. “We see burning vehicles ahead. Looks like they know we’re coming.”

He popped up in the turret, binoculars pressed to his eyes.

He could see German positions dug in along a tree line, muzzle flashes flicking. A narrow road cut through the fields, lined with ditches.

“Infantry ready?” he shouted down.

A company of armored infantry clustered behind the tanks, crouched in the snow, weapons ready.

“Ready as we’ll ever be,” their lieutenant said.

Boggs took a breath.

“All right,” he said. “No point in getting fancy. We smash them.”

He ducked back into the turret.

“Driver, forward,” he said. “Gunner, take anything that shoots. Loader, keep that gun hot.”

The Sherman roared forward, turret swinging.

The last fight before Bastogne lasted minutes that felt like days.

German anti-tank rounds punched into a Sherman on the right—BOOM, flames. An American tank destroyer fired back, its 76mm gun cracking.

Infantry dashed from crater to crater, firing, tossing grenades.

Somewhere in the confusion, an American GI ran past Boggs’s tank, yelling something.

“Bastogne’s just over there!” he shouted. “You’re almost there!”

Boggs gritted his teeth.

“Then let’s not be late,” he muttered.

Finally, the German fire slackened.

A white cloth appeared on a stick from one of the dugouts.

Boggs ignored it. His orders were forward.

“Move!” he shouted.

The tanks rolled on.

Behind them, a narrow corridor had opened—no more than five hundred yards wide, like a wounded artery.

It was enough.

Bastogne

Afternoon, December 26

In a battered building on the southern edge of Bastogne, Joe Miller heard a shout.

“Armor! Friendly armor!”

He grabbed his rifle and stumbled outside with DeLuca.

Down the road, past the smashed houses and shell holes, he saw them.

Shermans.

American Shermans.

They rolled into view with their guns elevated, turrets open. Tankers in dirty helmets and wool caps waved, grinning, their faces gray with exhaustion and smoke.

Someone near Joe started cheering. Another GI fired his rifle into the air, whooping.

Joe felt something in his chest lift that he hadn’t even known was there.

“Looks like Santa found us,” DeLuca said, laughing, his voice cracking with emotion.

One of the tanks ground to a halt near their position. A tanker popped out of the turret, looking around like he expected confetti and a brass band.

“Which way to the party?” he called.

Joe grinned so hard his cheeks hurt.

“You’re a little late,” he shouted back. “But we saved you a seat.”

The tanker saluted with two fingers.

“Compliments of Third Army, courtesy of General Patton,” he said. “Now let’s make this corridor bigger before Jerry decides to shut it.”

The linkup was, in purely tactical terms, small—a narrow passage, easily threatened by German counterattacks.

In human terms, it meant everything.

For the men inside Bastogne, it meant they were no longer alone.

For the Germans, it meant their encirclement was broken.

For Patton, back at his HQ, it meant the first part of his promise was kept.

In his journal that night, he wrote his wife: “We reached Bastogne as I had planned… destiny sent for me in a hurry when things got tight.”

Brandenberger’s HQ

Same time

The news filtered in slowly, like cold seeping through walls.

First it was a radio report: “Enemy armor seen south of Bastogne.”

Then: “American tanks have broken through near Assenois.”

Then: “Bastogne’s encirclement is compromised. Situation unclear.”

General Brandenberger stared at the map.

The big arrow westward—the proud, thick thrust of the offensive—now had a jagged notch at its base.

“If they widen that,” he murmured, “they can cut off our spearheads.”

His operations officer swallowed.

“We thought the weather would be our ally,” the man said. “We assumed… we assumed they would not move so fast in winter.”

Brandenberger didn’t answer.

His mind went back to staff briefings weeks earlier, when some had raised the possibility of an American counterattack from the south. The consensus had been that Patton was dangerous, yes, but even he couldn’t reposition his army in days under such conditions.

He thought of a quote he’d once read from some old Prussian officer: “No plan survives contact with the enemy.”

Hitler’s plan was dying on the roads.

Third Army HQ

Night, December 26

The mood in the operations tent wasn’t exactly celebratory.

Men were too tired, losses too fresh, the job too far from finished.

But there was a current of grim satisfaction running under the fatigue.

Harding hung a small American flag pin on the map over Bastogne.

“Linkup achieved, 26 December,” he said softly. “Merry damn Christmas.”

Jim Carter smiled, then caught himself yawning.

Patton stood at the map table, the glow of a single bulb highlighting the creases in his face.

“Don’t think this is over,” he said to his staff. “We relieved Bastogne. Good. But the Kraut still has armor out there. Still has teeth. Now we turn this rescue into a slaughter.”

He pointed at the bulge on the map, the German salient.

“We’re going to pinch this thing off from both sides,” he said. “North and south. We’re going to make this their Verdun.”

He looked at Jim.

“Make sure every son of a bitch in the Third Army knows what he just did,” he said. “We turned six divisions ninety degrees in three days, in a damned blizzard, and hit the enemy where he least expected it. I want them to know they did something every book said couldn’t be done.”

“Yes, sir,” Jim said.

Patton nodded once.

“And tell them,” he added, “that the Kraut stuck his head in the meat grinder, and I’ve got hold of the handle.”

He said it casually, almost conversationally.

It would be one of the lines that followed him forever.

In the weeks that followed, the Bulge would turn from a desperate crisis into a grim cleanup.

The snows would stay. The fighting would be savage—hedgerow to hedgerow, village to village, in conditions that made even veteran soldiers shudder remembering them.

By mid-January, American forces from north and south would link up near Houffalize, literally squeezing the bulge back into a line.

The German losses would be catastrophic: over 100,000 casualties, more than 700 tanks and assault guns, 1,600 aircraft. The last reserves of Hitler’s Western Front, squandered in a gamble that had briefly threatened to split the Allies and then broken on American resolve and cold steel.

But in those last days of December, as Shermans rolled into Bastogne and P-47s turned German supply routes into flame, the key decision had already paid off:

A general had said “forty-eight hours” when everyone else thought in weeks.

An army had moved when textbooks said it shouldn’t.

Men had endured cold that manuals couldn’t describe.

And a hole in the line had become the mouth of a meat grinder—but not for the side that opened it.

Part 3 – Meat Grinder Closed

Early January 1945

Somewhere in the Ardennes

Private Joe Miller had stopped feeling his toes sometime around New Year’s.

He wasn’t entirely sure they were still attached. When he wiggled them inside his boots, he got something back that felt more like memory than sensation.

The ring around Bastogne was broken now. Third Army had punched in, units from other armies had linked up, and the front had shifted. The town was no longer an island. It was a crossroads again—and crossroads in this war meant traffic and blood.

Joe’s outfit had been pulled out of Bastogne itself and pushed east, part of the grinding effort to flatten the bulge back into a line.

“Happy New Year,” DeLuca said, blowing into his hands as they trudged along a churned-up forest track. Snow fell in fine, relentless flakes.

“Yeah,” Joe said. “New year, same war.”

German resistance hadn’t disappeared just because Hitler’s timetable had gone to hell.

Panzer units that had once driven west with bravado were now trying to fight their way back east through narrowing corridors, low on fuel and ammunition. Volksgrenadier divisions made up of boys and old men clung to villages and road junctions, ordered to hold “to the last round.” SS units fought with fanaticism that made even hardened GIs mutter.

For the Americans, the fight was no longer about preventing a breakthrough. It was about squeezing.

“Feels weird,” DeLuca said as they dropped into yet another snow-filled ditch, taking cover behind a dirt berm. “Taking back the same crap we gave ‘em up front.”

“They borrowed it,” Joe said. “We’re just collecting the interest.”

He peered over the berm.

Ahead, the remains of a small Belgian village huddled in the snow. Roofs partially collapsed. A church steeple leaning drunkenly. German machine-gun fire flickered from shattered windows.

Somewhere off to their right, an American Sherman fired. The shell blew a chunk out of a stone wall, snow and masonry burst outward.

“Company, forward!” someone yelled.

Joe clenched his rifle tighter.

“Here we go again,” he muttered, and climbed.

Third Army HQ

January 3, 1945

Jim Carter had stopped trying to keep his uniform clean. The mud and melted snow found him no matter what he did.

He stood at the big map in the dim light of the operations tent. The bulge didn’t look like a neat shape anymore. The once-proud German salient was jagged, dented from north and south, the arrows now pointing backward.

“You know,” Harding said, stepping up beside him with a mug of coffee, “a month ago I thought this whole map was going to end up in a museum labeled ‘How We Screwed Up.’”

“Still might,” Jim said. “But maybe with a different caption.”

Harding snorted.

“‘How We Un-screwed It,’” he suggested.

“Catchy,” Jim said.

They watched as a clerk replaced one red pin with a blue one—another town recaptured, another road junction back in American hands.

Reports were stacked in trays.

Fourth Armored engaged near Villers-la-Bonne-Eau. Heavy casualties but enemy pushed back.

26th Infantry making slow progress in woods east of Bastogne. Enemy resistance stiff.

Weather continuing cold. Frostbite cases increasing. Recommend priority for winter gear.

The Bulge wasn’t going away with one dramatic breakthrough. It was dying by inches.

“You seen the casualty tallies?” Harding asked quietly.

“Yeah,” Jim said.

American losses for the campaign were already climbing into the tens of thousands. German casualties were worse—over a hundred thousand by some estimates—but knowing the enemy was bleeding more didn’t make frozen corpses on your own side any easier to look at.

Patton stepped into the tent, brushing snow from his shoulders.

He went straight to the map, eyes flicking over the colored pins.

“Good,” he said. “They’re pulling back faster than we’re going forward. Keep hitting them.”

He glanced at Jim and Harding.

“You two look like you’ve been run through the wringer,” he said.

“Just trying to keep up with you, sir,” Harding said.

Patton gave a brief, tight grin.

“This is the ugly part,” he said. “No glamour. No big arrows. Just slogging and killing until the numbers come out in our favor. The Kraut still knows how to fight. Don’t let anyone tell you different. But he’s running on fumes now. Every Tiger we knock out, he can’t replace. Every seasoned infantryman he loses, he’s got to swap in a sixteen-year-old.”

He jabbed a finger at the map.

“Bradley and Hodges squeeze from the north, we squeeze from the south,” he said. “We meet in the middle and close the lid on this damn thing.”

Harding hesitated.

“Sir,” he said, “if I may… the Germans misjudged us. Again. They thought winter and weather would slow us. They thought we couldn’t coordinate something like this.”

Patton’s eyes narrowed.

“Yeah,” he said. “They thought we were soft. Thought we needed warm socks and hot chow to move. They forget we’ve been learning this game for two years now. North Africa, Sicily, Normandy, Lorraine… this army is not what we were in ’42.”

He looked up, eyes hard.

“And I am not just a pursuit commander,” he added quietly, more to himself than to them.

Jim understood.

There had been whispers earlier in the fall, when Metz turned into a slog. That Patton was good when the enemy was running, less good when the enemy stood and fought. That he needed open country and fluid situations.

The Bulge had been anything but fluid at first. Chaos, yes. Fluid, no.

Patton had turned it into his kind of battle anyway, by sheer force of will and logistics.

“We moved six divisions in three days,” he said, as if reading Jim’s mind. “In this. While in contact. That’s not pursuit. That’s maneuver. That’s what war looks like when you do it right.”

He straightened.

“Tell the men we’re not just cleaning up a mess,” he said. “We’re finishing a German mistake. Hitler bet his last reserves on this and he’s losing. Every day of this grind is one step closer to Berlin.”

He walked to the tent flap, then paused.

“And tell them this too,” he added over his shoulder. “When Churchill calls this the greatest American battle of the war—and he damn well will—he’s talking about them, not me.”

Jim didn’t know yet that Churchill would say almost exactly that in a speech to Parliament, calling the Ardennes fight “undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war.”

But Patton’s instinct for the historical line was almost as sharp as his instinct for maneuver.

German Lines

Mid-January 1945

Private Karl Richter no longer believed in the offensive.

He wasn’t sure he believed in much of anything now, beyond the immediate questions of warmth, food, and whether the next shell would land close.

The German advance had halted weeks ago. The furthest units had gotten within sight of the Meuse and then been forced back. Fuel ran out. Supplies never arrived. Orders became more desperate—“hold at all costs,” “counterattack immediately,” “no step back.”

Karl had watched older non-commissioned officers—men who’d fought in Poland, France, Russia—shake their heads at orders of “immediate counterattack” when their companies were down to a handful of freezing, hungry men.

“Insanity,” one sergeant muttered. “They think we’re still in ‘40.”

The reality was mud, ice, and American artillery.

The Americans had a way of responding to German attacks that Karl found unnerving. They didn’t panic. They didn’t run in circles. They called down artillery like rain.

On a particularly bad day, when Karl’s unit had tried to hold a wooded ridge line, American shells had pounded the trees until they exploded, sending splinters scything through the air. Men died not from bullets but from wood turned into daggers.

Now, his company—what was left of it—was falling back again, deeper into the woods, toward the old frontier.

“Richter!” his lieutenant shouted. “Take your squad and cover the road. The Americans are pushing from the south.”

Karl moved through the snow, every step an effort. He thought of home—a city increasingly under Allied bombing. Of his mother’s last letter, months old now. Of the absurd speeches on the radio still talking about “final victory.”

He ducked into a roadside ditch and peered over the snowy bank.

In the distance, the sound of engines grew—steady, relentless.

He could not see them yet, but he knew what was coming: Shermans, half-tracks, infantry in winter gear that looked warmer than his own thin coat.

For the first time since joining the army, Karl wondered not how to stop an enemy, but how to survive until someone decided this madness was over.

Houffalize

January 16, 1945

The snow in Houffalize was black and gray, churned by treads, boots, and explosions.

The town itself was barely a town anymore. Roofs were gone. Walls had holes. The river Ourthe ran sluggishly under a bridge that had somehow survived everything thrown at it.

On the southern edge, a column of Third Army tanks rolled in, engines rumbling.

On the northern edge, tanks from the First Army rumbled in from the opposite direction.

In the lead Sherman of a Third Army unit, Lieutenant Boggs squinted through the periscope.

“Looks like we beat the mail,” he said.

His radio crackled.

“Red One, this is Red Six,” came the battalion commander’s voice. “Keep your eyes open. First Army elements are approaching from the north. Don’t shoot the good guys.”

Boggs grinned.

“Roger that,” he said. “We’ll try not to start an inter-service incident.”

He turned to his crew.

“Eyes peeled, boys,” he said. “Let’s see if anyone up there looks uglier than we do.”

They crept forward through the shattered streets, main gun elevated.

Then, through the smoke and dust, another Sherman appeared—this one with a different tactical number painted on its hull, different markings.

It stopped.

Boggs’s tank stopped.

For a heartbeat, the two crews just stared at each other.

Then both turrets popped open. Tankers climbed halfway out, waving.

“Where the hell you been?” someone from First Army shouted.

“Taking the long way around,” Boggs yelled back.

Infantrymen shook hands in the middle of the street, helmets knocking, grins splitting chapped faces.

One GI from First Army held up a cigarette pack.

“Trade you one of these for a hot cup of whatever you got,” he said.

“Buddy, if we had anything hot, we’d be drinking it ourselves,” a Third Army guy replied.

They laughed, the sound brittle and exhausted and very human.

Behind them, staff officers were already marking on maps: January 16 – linkup near Houffalize. Bulge effectively eliminated.

On the German side, what remained of the spearhead forces were either dead, captured, or limping back toward the Siegfried Line. The “Watch on the Rhine” had become a rout, not in one dramatic collapse, but in a long, grinding squeeze.

Third Army HQ

Aftermath

Numbers came in like casualty lists always did—cold, impersonal, almost obscene in their detachment from the faces behind them.

German losses in the Ardennes: over 100,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. Roughly 700 tanks and assault guns destroyed or abandoned. Around 1,600 aircraft lost.

American casualties: around 80,000—killed, wounded, missing, and captured.

Third Army’s share of the fighting had been heavy. Battalions were down to skeleton strengths. Tank companies had more holes in their rosters than in their armor. Medical units were overwhelmed—not just by battle wounds, but by frostbite, trench foot, and pneumonia.

In a rare quiet moment, Jim Carter sat on an ammo crate outside the ops tent, flipping through a report.

Patton came out, hands in his overcoat pockets, breath steaming.

“Mind if I sit?” the general asked.

Jim blinked.

“Of course, sir,” he said, scooting over.

Patton lowered himself onto the crate with a soft grunt.

“You look like hell, Carter,” he said.

“Just following your example, sir,” Jim said.

Patton snorted.

They sat in silence for a moment, watching a column of trucks rumble by, heading back toward supply dumps.

“Sir,” Jim said, “they’re already saying this is the greatest American battle of the war. Churchill said something like that in a speech.”

Patton gazed out at the snow.

“They can call it whatever they want,” he said. “Greatest, worst, coldest. Doesn’t change what it was to the men in it.”

He tapped his chest lightly.

“But I’ll tell you this,” he went on. “If we hadn’t turned when we did, those boys in Bastogne would be dead or in cages. The Germans would have gotten farther. Maybe not to Antwerp, but far enough to make this spring a bloodbath we couldn’t imagine.”

He looked at Jim, eyes clear.

“I’ve made mistakes,” he said. “More than my share. I’ve said stupid things. I’ve done things I regret. But when destiny called at Verdun and asked, ‘Can you move?’ I said, ‘Yes, and fast.’ And I wasn’t lying.”

Jim nodded.

“It was one of the most incredible logistical feats in history, sir,” he said. “Six divisions, ninety-degree turn, one hundred miles, three days, in a blizzard. The manuals… they say you don’t do that.”

Patton smiled faintly.

“Manuals are written so cowards can have something to hide behind,” he said. “War favors the audacious. The man who attacks when the other fellow is still making excuses.”

He looked back toward the east, where Germany lay under snow and ruin.

“Hitler thought winter would save him,” Patton said. “He thought we’d hide in our tents, that our generals would freeze like his did before Moscow. He bet his last reserves on that. And he lost.”

He stood, joints cracking.

“You remember this, Carter,” he said. “When some historian writes about all this, they’ll talk about Bastogne and ‘Nuts’ and my prayer and the Bulge and all that. Fine. But underneath it, the truth is simple: we believed our soldiers could do the impossible. And so they did.”

He started to walk away, then paused once more.

“And somewhere right now,” Patton added, “there’s a German general saying to himself, ‘We never thought they could do that.’ That’s the highest compliment you’ll ever get from an enemy.”

Then he was gone, striding toward another meeting, another map, another set of orders.

Jim watched him go.

He thought of North Africa, Sicily, Lorraine—the whole arc of Patton’s fighting career. The slapping incidents, the exile, the redemption. The Germans’ fear of him. The Allied deception campaign that had used his reputation like a weapon.

He thought of a quote he’d heard from a captured German general, von Manteuffel or maybe Blumentritt—something like, “Of all the Allied generals, we regarded Patton as the most dangerous. He fought war as we did.”

Jim smiled to himself.

Yeah, he thought. And then some.

Far from HQ

Spring 1945

Indiana & Brooklyn

By the time the snow melted in the Ardennes and the war ground on into Germany proper, men like Joe Miller and Tony DeLuca were thousands of miles from the lines where they’d almost frozen.

Joe stepped off a train in Indiana with a duffel over his shoulder and a hole in his boot where frostbite had taken a toe.

His father hugged him so hard his ribs creaked. His mother cried and pushed food at him until he thought he’d explode.

At the diner in town, old men who’d fought in the last war clapped him on the back and asked about Bastogne. The papers had run stories—“American ‘Nuts’ Reply Stuns Reich,” “Patton’s Third Army Saves the Day.”

Joe found himself groping for words.

“How do you even begin to describe that?” he asked his dad one night, sitting on the back porch as spring peepers chirped in the fields.

“Slowly,” his dad said. “And with a lot of silence in between.”

In Brooklyn, DeLuca sat in a bar on Flatbush, just like he’d imagined in that frozen foxhole.

His ma had cried and yelled and fed him like she’d promised. His old buddies slapped him on the back and said he looked like hell. He told them he’d seen worse.

On the bar’s little radio, a newsreader talked about the “Battle of the Bulge” and how it would go down as “an American epic.”

DeLuca sipped his beer.

“Epic,” he muttered. “Yeah. That’s one word for it.”

He thought of the frozen foxholes, the snow turning red, the nights begging for the sun to come up even if it meant more artillery.

He thought of a Sherman tank clanking into Bastogne, a tanker leaning out and yelling, “Compliments of Third Army!”

He raised his glass.

“To the crazy old man,” he said.

The bartender, who’d lost a nephew at Salerno, nodded.

“To all of ‘em,” he said.

They drank.

Berlin, some years later

A different kind of war room

A group of former German officers sat in a lecture hall, gray-haired and stiff-backed, answering questions from Allied historians.

One of them—General Blumentritt, once a staff officer on the Western Front—leaned on his cane as he spoke.

“We misjudged the Americans,” he said in accented English. “In the beginning, we thought them clumsy, too dependent on material. But they learned. And they had leaders who understood mobile warfare.”

He paused, eyes distant.

“Patton,” he said, “we regarded extremely highly. He was aggressive, fast, flexible. In some ways, he came closest to our own concept of what a classical commander should be. When he turned his army in the Ardennes, we were… surprised. That he could do it so quickly, under such conditions…”

He shook his head.

“We did not believe any Allied force could maneuver like that in winter,” he admitted. “We assumed the Americans would be even more paralyzed by the cold than we were. That was a fundamental error.”

He looked out at the audience.

“One must respect one’s enemy,” he said quietly. “Or one will have one’s nose broken by him.”

A chuckle went through the room.

In the back, a young American officer scribbled in his notebook.

They thought winter + surprise + our reliance on comfort would equal victory. They forgot about guys who drive trucks through blizzards and generals who say ‘forty-eight hours’ with a straight face.

Years after the war

Arlington National Cemetery

Snow dusted the rows of white headstones.

Visitors walked quietly among them, scarves up, breath steaming in the cold air.

At one stone, a middle-aged man in a nice overcoat stopped. He ran his gloved fingers over the letters:

GEORGE S. PATTON, JR.

GENERAL, U.S. ARMY

1885–1945

He’d died not in battle, but in a peacetime car accident after the war. For a man who’d survived shrapnel and bullets and artillery, it seemed almost insulting.

The visitor—an Army colonel—stood there a long moment.

He thought of the Bulge.

Of Verdun, where Patton had said “forty-eight hours.”

Of the thousands of nameless men who’d tramped north through snow because he told them to.

Of the Germans who’d joked about American soft bellies and then found themselves under Third Army tracks.

He snapped a salute.

“Sir,” he said quietly, “for whatever it’s worth, you answered when destiny called. And we’re still reading about it.”

He dropped his hand, turned, and walked back down the line.

Behind him, the stone stayed where it was, white against the winter sky.

In the end, the Battle of the Bulge was not decided by a single act of heroism or a single stroke of genius, though it had plenty of both.

It was decided by a thousand intertwined factors:

– German overconfidence in their ability to move undetected and sustain an offensive with limited fuel.

– Allied failures in intelligence, corrected not by denial but by swift, painful acknowledgment.

– The stubborn defense of surrounded units like the 101st Airborne at Bastogne, who answered “NUTS” when told to surrender.

– The opening of the skies, turning the Luftwaffe’s last gasp into a slaughterhouse for their transport and armor.

– And, at a crucial hinge point, a general in an olive-drab helmet who looked at an impossible situation and saw an opportunity.

Patton’s pivot in the Ardennes broke more than just a German encirclement.

It broke the illusion that the Germans still had the strategic initiative in the West.

It broke the myth that American armies couldn’t act fast in bad conditions.

It broke the back of Germany’s last great reserve in the theater.

Hitler had hoped the Ardennes offensive would be his final trump card, splitting the Allies, seizing Antwerp, forcing negotiations.

Instead, it burned through his last chips and left him more exposed than ever.

The snow in the Ardennes did indeed turn crimson.

But not in the way Hitler had imagined when he stared at his big red arrows on the map.

In that frozen forest, American soldiers—led by commanders like Patton, supplied by convoys like Jackson’s, supported by pilots, medics, engineers, and countless others—proved they could do more than just advance behind someone else’s retreat.

They proved they could take a punch, pivot on the spot, and hit back harder.

And they did it in the coldest winter anyone could remember.

Anywhere, anytime, any enemy.

That was the promise Patton made when he turned north.

The Germans, who had laughed at American comfort and soft living in December, weren’t laughing in January.

They were retreating.

THE END

News

A MAID DISCOVERS THE BILLIONAIRE’S MOTHER LOCKED IN THE BASEMENT… BY HIS CRUEL WIFE…

No one in the mountain mansion imagined what was happening beneath their feet. While luxury glittered in the salons and…

Undercover black boss buys a sandwich at his own diner, stops cold when he hears 2 cashiers…It was a cool Monday morning when Jordan Ellis, the owner of Ellis Eats Diner, stepped out of his black SUV wearing jeans, a faded hoodie, and a knit cap pulled low over his forehead.

It was a cool Monday morning when Jordan Ellis, the owner of Ellis Eats Diner, stepped out of his black SUV…

The sound of my daughter’s scream—a high-pitched, tearing shriek of pure terror—will haunt me until my last breath. It’s been three years since that dinner, and I still wake up sometimes in the middle of the night, heart pounding against my ribs, reliving those few seconds that shattered my world and changed everything.

The Dinner That Changed Everything The sound of my daughter’s scream—a high-pitched, tearing shriek of pure terror—will haunt me until…

The billionaire’s baby wouldn’t stop crying on the plane until a child did the unthinkable. The cries were incessant.

THE HARMONICA THAT CALMED THE SKY I. THE FLIGHT THAT SHOOK A BILLIONAIRE The cries began the moment the cabin…

My 11-year-old daughter came home and her key didn’t fit. She spent five hours in the rain, waiting. Then my mother came out and said, “We have all decided you and your mom don’t live here anymore.” I didn’t shout. I just said, “Understood.” Three days later, my mother received a letter and went pale…

It was just a normal day at work. Busy, chaotic. I was running on three hours of sleep and one…

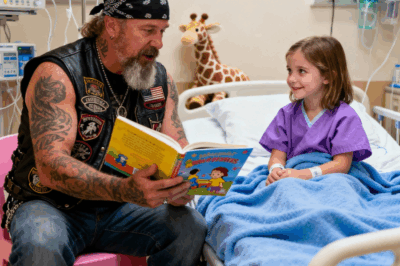

The little girl asked if I could be her daddy until she dies but I refused because of one thing. Those were her exact words. Seven years old, sitting in a hospital bed with tubes in her nose, and she looked up at me—a complete stranger, a scary-looking biker—and asked if I’d pretend to be her father for however long she had left.

A Dramatic Reimagining I’ve lived fifty-eight years on this earth, and I’d thought I’d seen every kind of heartbreak a…

End of content

No more pages to load