Story title: The Tables Were Set

1. Tunisia, 1943 – The End of One Future

On the night Joseph Huber buried his medical school application under a loose floorboard in his parents’ Munich apartment, he thought he was only postponing a dream.

War, everyone said, would be brief. Decisive. He’d do his duty in uniform, then return to the Bavarian mountains and white lecture halls and the clean, controlled world of anatomy and physiology.

Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939.

The Wehrmacht needed men who could operate radios, lay cable, keep the cracks between units wired together. Joseph had liked tinkering with electronics as a boy. He had good grades.

The Luftwaffe took him instead.

Three years in North Africa carved themselves into his bones.

Heat that pressed down like a hand.

Sandstorms that stripped paint from vehicles.

Days of blistering sun and nights cold enough to make teeth chatter.

He learned the names of men he’d never meet—Rommel, Montgomery, Patton—because the officers spoke them as if they were the weather, forces you lived under but could not change.

In May 1943, the weather turned.

The Allied trap closed around Tunisia.

Eighty thousand German soldiers found themselves backed against the sea.

The order, officially, was fight to the last round.

Unofficially, every man could see what that meant.

Surrender.

Or die in a corner of Africa no one back home could find on a map.

Joseph and a handful of comrades decided on a third option.

“Morocco,” one said, jabbing a finger at a half-ruined map. “If we cross the desert, slip past the French, we can reach Spanish territory. Internment. Neutrality.”

It sounded like suicide.

It sounded better than walking into Allied lines and hoping rumor was wrong.

They moved at night for twelve days, covering ten to fifteen miles between sunset and dawn, sleeping in wadis during the day, listening to dogs bark in distant Berber camps and freezing whenever voices came too close.

The French in Tunisia had not forgotten German support for Berber uprisings. Neutral ground might as well have been the moon.

On the twelfth dawn, Joseph woke stiff and hungry, sand in his teeth, and realized three things at once:

His boots were falling apart.

Morocco was still impossibly far.

And his dream of outrunning the war was finished.

“We go to the British,” he said. “Not the Americans. At least we know the British.”

He didn’t know the Americans at all.

An English lieutenant accepted their surrender with tired efficiency.

He handed them over to two American military policemen.

“Welcome to the other side, boys,” one of the Americans said in accented German.

Joseph was too exhausted to answer.

He was just glad the shooting had stopped.

2. New York – A World Intact

They moved like cargo.

Truck to port, ship to Gibraltar, ship to Scotland, then six weeks in a camp where the rain never stopped and the food was gray but steady. The war still felt close there—blackout curtains, air raid warnings, soldiers with haunted eyes.

Then came the big ship.

Across the Atlantic, the holds that had carried Sherman tanks east now carried German prisoners west.

They were issued blankets—two per man.

Red Cross parcels arrived daily—canned meat, chocolate, cigarettes, powdered milk.

Nobody starved.

Nobody brawled over the last crust.

Joseph kept waiting for the cruelty to begin.

It didn’t.

Instead, they disembarked one day at a place called New York.

He’d seen pictures in magazines before the war—tall buildings, crowds—but the reality hit like artillery all its own.

The sheer scale of Penn Station pushed the breath out of him.

Marble floors, high vaulted ceilings, electric lights brighter than noon in Tunisia. Thousands of people surged in streams—women in hats, businessmen in suits, children tugging their mothers’ coats, American soldiers with duffel bags.

The prisoners marched through the concourse in columns, their uniforms stained and ill-fitting.

New Yorkers parted around them like a river around rocks.

Some faces were hostile.

Some curious.

Most… indifferent.

German prisoners were just another thing the city had seen.

Joseph’s boots echoed on stone as they descended to a platform, climbed into train cars.

The train itself seemed impossibly large.

The guard said a word that meant nothing to him.

“Mississippi,” the man announced. “You’re going to Mississippi.”

Another foreign name to fit next to “Tunisia” and “Scotland” in the growing list of places that were not Bavaria.

The train ride took days.

Guards passed out sandwiches, apples, canteens of water.

Joseph bit into the apple and almost wept.

Crisp.

Sweet.

Fresh fruit.

For a prisoner.

Through the window, America rolled by.

Endless farmland, fields stretching to horizons unmarked by bomb craters. Forests dense and green, not stripped and splintered by shellfire. Towns with intact roofs. Neon signs blinking in windows. Stores whose fronts displayed actual goods instead of “Sold Out” signs.

In Europe, war had carved itself into the landscape.

Here, it seemed to be an export.

A country at war—but not a country of ruins.

One prisoner, staring at the passing scenery, murmured, “We cannot win. Even if they told us we could, now I know we cannot.”

Joseph understood.

No amount of propaganda could stand against the sight of full silos and busy factories.

3. Camp Clinton – The Silverware Moment

Camp Clinton lay in Mississippi pine woods, a grid of white barracks and wire, guard towers and gates.

Heat hit Joseph in the face when he stepped off the train—thick, humid, different from African heat but no less overwhelming.

He expected the rest.

Barbed wire.

Searchlights.

Lines.

He did not expect what he saw when he walked into the camp dining hall.

He expected mess tins, the familiar clamor of metal on metal.

What he saw instead made him stop mid-step.

Tables.

Set tables.

White plates gleaming in rows.

Not enamel, not tin.

Porcelain, with a thin blue line around the rim.

On either side of each plate lay a knife and fork.

Actual silverware.

Not wood.

Not hands.

“The first time I saw the set tables,” he would say decades later, “my world… cracked.”

In three years of war, he had eaten from tins, crouched in sand, standing on one foot in mud. He had drunk lukewarm coffee from battered canteens. He had shoveled down rations designed to keep bodies functioning, not to make anyone feel like a person while doing it.

Now, in a prison camp in Mississippi, the tables were laid as if a family were about to sit down.

He gripped his tray a little tighter.

The line moved.

Food slid onto plates—meat, potatoes, something green. Bread. Coffee.

He sat.

He picked up the fork with fingers that had forgotten the feel of it.

The men around him did the same, glancing at one another, half-expecting someone to yank the plates away and shout that it had all been a mistake.

Nobody did.

They ate.

It wasn’t a feast by American standards.

By Joseph’s, it felt obscene.

Not because it was too much.

Because it was for them.

For prisoners.

“We were treated well,” he would say, the words sounding almost insufficient for what they contained.

4. The Hospital – A Dream Resurrected

Camp Clinton turned out not to be the grim place he’d mapped in his mind when he’d heard the word pow camp.

The barbed wire was real.

The guard towers were real.

So were other things.

A library.

Orchestras—jazz, symphony.

Theater groups.

Work details that paid eighty cents a day, credited to prisoner accounts.

One afternoon, a clerk called his number.

“Huber, Josef,” the man read off a list. “Hospital. Report to the main infirmary.”

Joseph went, expecting latrine duty or floor-scrubbing.

He found, instead, a ward full of white sheets, polished metal, and American nurses in starched uniforms.

Someone had read his file.

Someone had seen the words “medical school application” and decided that was worth something.

“You’re going to train as a surgical technician,” the camp doctor, a captain with square shoulders and a tired face, told him. “We need hands. You have a head. We’ll use both.”

In Germany, enemy prisoners scrubbed floors.

Cleaned latrines.

Hauled supplies.

No one, in his wildest imagination, would have said, “Let’s teach an enemy prisoner advanced medical procedures.”

Here, it was policy.

He was assigned to work under a nurse named Marion Rogers Wells.

She was in her twenties, hair pulled back in a bun, eyes sharp over the edge of her mask.

The first week, they communicated in gestures and Latin.

Scalpel.

Clamp.

Retract.

“Watch,” she would say, pointing. Then, after demonstrating once, “Now you.”

He watched.

He did.

His hands remembered what they’d wanted to learn in Munich before war ripped that future away.

By the second week, a pattern settled in.

She corrected him gently.

She answered his questions patiently.

She explained why they did what they did, not just the how.

She never, not once, spoke to him as if he were less capable because of the uniform he’d arrived in.

“We worked together for a year,” she would say later, years after she’d left the Army, as if describing the most ordinary thing in the world.

For Joseph, each day felt like a small miracle.

5. Jazz, Theater, and 80 Cents a Day

If the hospital revived his medical dreams, the camp’s cultural life resurrected parts of him he’d forgotten existed.

On Thursday nights, the jazz orchestra set up in the recreation hall.

Prisoners filled benches.

Guards leaned against walls.

The first night, Joseph went because there was nothing else to do.

Jazz had been in the Reich’s black book—“degenerate,” “Negermusik.” He’d only ever heard snatches on forbidden records, quickly shut off if a Party member entered the room.

Now, in an American camp, German prisoners played American music on American instruments, and American guards tapped their feet to the beat.

Drums.

Bass.

Piano chords rolling like waves.

Saxophone lines curling around each other like smoke.

The melodies were strange, the improvisation wilder than anything Bach would have tolerated, but under it all Joseph felt something he recognized.

Freedom.

Not physical.

Something inside.

The theater group performed twice a month.

They put on improvised plays, satirical sketches, bits of Shakespeare and Schiller adapted to their situation.

The symphony orchestra—only twelve members, but serious—practiced Bach and Beethoven and Mozart.

German composers, in an American camp.

He sat in the back, listening, letting the music remind him that beauty had not been fully bombed out of the world.

As for the eighty cents a day, it wasn’t wealth.

But the ability to decide what to do with it was.

Cigarettes.

Chocolate.

Writing paper.

Soap.

The canteen was small, but its shelves represented something enormous: the idea that his labor, even as a prisoner, had value measured in something other than survival.

6. The Surgery That Changed Everything

Late in the summer of 1944, they wheeled a new patient into the operating room.

Another gunshot wound, Joseph thought, wiping his hands at the scrub sink.

Then he glanced at the chart.

Corporal James Morrison.

Age twenty-three.

United States Army.

A work detail accident, the surgeons said. A rifle had gone off when it shouldn’t have.

The bullet had shattered the bone in the man’s leg and torn through muscle. Without surgery, infection and amputation would follow.

The team assembled as always.

Surgeon.

Nurse Marion.

Surgical tech.

Anesthetist.

This time, the surgical tech was a German prisoner.

Nobody commented on it.

Nobody suggested he be kept away because the patient wore a different flag on his sleeve.

Inside the operating theatre, everyone wore the same clothes—green gowns, gloves, masks.

The body on the table was just that—a body, with damaged tissue that needed to be repaired.

They worked as they always did.

Cut.

Clamp.

Remove bone fragments.

Set the leg.

Repair the muscle.

As Joseph held a retractor, watching the surgeon’s hands move, he realized how unremarkable it seemed to everyone else that he was there.

In Germany, the idea of an enemy prisoner assisting in surgery on a guard would have been laughable.

Then grounds for punishment.

Here, it was simply… Tuesday.

Three weeks later, he saw Morrison walking—limping, but upright—past the hospital building.

Their eyes met for a moment.

Morrison nodded once.

“Thanks, Doc,” he said.

Two words.

Joseph felt something in his chest give way.

Not from guilt.

From the weight of a conviction he hadn’t known he was carrying: that enemies stayed enemies forever, that war’s lines were permanent.

That nod said otherwise.

7. Letters and Contrasts

He wrote to Gertrud every Sunday.

Sometimes the letters returned, red-stamped, “Undeliverable.” Sometimes they vanished entirely.

Sometimes, miraculously, they arrived.

He knew because every so often, months late, a reply appeared.

She wrote of Munich under bombs.

Of nights in basements while Allied planes droned overhead.

Of mornings spent hunting for food that wasn’t there.

Of friends killed.

Of houses flattened.

The Munich he described—Jazz on Thursdays, symphonies once a month, well-lit wards, tables set with white plates—would have sounded like fantasy.

So he didn’t write that.

He wrote about medicine.

About surgical procedures.

About veins and nerves and instrument names.

He wrote about the dream stubbornly resurrecting itself inside barbed wire.

She understood that.

She had always been the one who quizzed him on anatomy terms in the evenings, sitting in the bookstore where she worked, while he memorized Latin names under yellow light.

Now, in ruins, she read about tendon repairs and appendectomies and knew the dream was not dead.

8. After the War – The Harder Half

Germany surrendered in May 1945.

A camp announcement. A radio broadcast. A faint cheer. A few muffled sobs.

Relief washed through Camp Clinton.

Then uncertainty.

The war was over.

Captivity was not.

The tables remained set.

The hospital continued operating.

The jazz played.

The orchestra rehearsed.

Life went on behind the wire, in a place where food was regular, work was meaningful, and bullets were not a daily concern.

Outside, Germany starved.

In 1946, the camp closed.

Prisoners were moved.

Joseph went to France.

The camp there was different.

No jazz.

No symphony.

No hospital work.

Just labor.

He cleaned debris.

He helped clear tracks.

He did the work of rebuilding for those his army had destroyed.

It wasn’t cruel.

It wasn’t gracious.

It was… ordinary.

After a year, he was discharged.

Discharge papers.

A train ticket to Munich.

A small packet of money.

Permission to leave.

9. Return to Bavarian Rubble

Munich in 1947 was not the city he’d left.

Whole neighborhoods were gone.

Piles of bricks where streets had been.

Church spires standing above seas of rubble like the masts of ships sunk in stone.

But Gertrud was alive.

She had survived four and a half years of bombs, ration lines, and the slow crushing of illusions about the regime they’d grown up under.

They met at the station.

Both thinner than they’d been at twenty.

Both older than their ages.

Both stunned for a moment that the other existed in three dimensions.

They married quietly.

There were no white gowns.

No big family gatherings.

Just a small room, a pastor in a threadbare cassock, and two people deciding that surviving together was better than surviving separately.

He applied to medical school.

Germany’s institutions were in ruins.

Buildings bombed out.

Faculty dead or de-Nazified.

Files missing.

But someone looked at his Camp Clinton records and said, “You have experience. That counts.”

It did.

While his classmates learned to scrub in, he already had callouses on his fingers where surgical instruments sat.

While they read about incision routes, he had made them.

He specialized—some sources say neurology, others urology. The exact discipline blurred in later accounts.

What didn’t blur was his competence.

His dedication.

The thirty years of medical practice that followed in Bavaria, treating peasants and businessmen, children and the elderly, working in hospitals that slowly modernized, in a country that slowly learned to live with what it had done.

Patients knew him as Dr. Huber.

They did not know that he had learned to hold a clamp in steady hands under a Mississippi sun.

10. Climbing Mountains, Playing Violin

After he retired, he climbed mountains.

The same Bavarian peaks he’d dreamed about on nights in Tunisia when the wind had howled and the stars felt too close.

He played violin in an amateur orchestra.

He’d fallen in love with the instrument listening to the Camp Clinton symphony—twelve prisoners coaxing Bach out of borrowed instruments while guards leaned against the walls, eyes closed.

Now he made the music himself.

He audited philosophy courses at Munich University.

Kant.

Aristotle.

Hannah Arendt.

He wasn’t chasing a degree.

He was chasing understanding—how nations went mad, how individuals navigated systems larger than themselves, how ethics survived in the cracks.

Through it all, he wrote letters.

To Gertrud.

To colleagues.

To friends in America.

One of those was Marion Rogers Wells.

They wrote for decades.

At first about medicine and camp memories.

Later about grandchildren.

Retirements.

Health scares.

Their friendship, born under fluorescent lights and scalpel blades, outlived the war by half a century.

11. The Reunion – Setting the Tables Again

In 1996, someone in Mississippi—no one remembered exactly who started it—organized a reunion at the old Camp Clinton site.

Ex-prisoners came from Germany, Austria, elsewhere.

Gray-haired men with grandchildren.

They walked through pine woods where barracks once stood.

Nothing remained but the ghosts of grid lines and the faint depressions where foundations had been.

Joseph stood at the place where the camp gates had been.

He saw it as it had been: guards, wire, a younger version of himself stepping through expecting punishment and finding possibilities instead.

Marion was there, too.

Older.

Hair white now.

Still with that sharpness in her gaze.

They embraced.

They laughed.

They cried.

“I came here expecting to find punishment,” Joseph said in his speech to the group, in English learned in that camp. “Instead, I found my future. Camp Clinton gave me back what the war had taken away.”

He thanked Marion.

He thanked the American administrators who had decided, in the middle of total war, that setting tables and equipping a POW hospital mattered.

He thanked a system that had treated him as more than a defeated body to be used up.

The site itself had no monument.

No plaque.

The memorial was in the people standing there.

Doctors.

Teachers.

Mechanics.

Grandfathers.

Men whose lives had unfolded along arcs that were only possible because someone in 1943 had made policy decisions that placed dignity above revenge.

12. The Legacy of Set Tables

Joseph died sometime in the early 2000s.

The exact date blurred in obituary notices.

What didn’t blur was his legacy.

Thirty years of practice.

Dozens of young doctors trained.

Hundreds of patients.

Thousands of encounters in exam rooms where competence and care mattered more than nationalities stamped in old record books.

His children inherited his love for mountains and music.

His patients remembered a physician who listened.

His story—told at family tables, at reunions, in classrooms—became one thread in the larger tapestry of how former enemies became friends.

Camp Clinton disappeared physically.

But its effects didn’t.

They lived on in the German-American partnerships that defined postwar Europe, in NATO, in student exchange programs, in tourists welcomed with “Grüß Gott” in Bavarian inns, in joint military exercises where former foes stood under the same flag.

And at the root of that cascade of effects were decisions that seemed small at the time.

To set the tables.

To stock the hospital.

To hire a nurse who believed teaching an enemy was worth her time.

To pay prisoners for their work.

To allow jazz and Bach inside the wire.

To treat men like Joseph Huber not as fixed enemies but as human beings who might, given the chance, become something else.

When nations today debate how to treat prisoners, how to handle defeated foes, how to break cycles of hatred, his story offers something rare:

Evidence.

Evidence that dignity is not naïveté.

That education in captivity can become skill in peace.

That the way you treat enemies today can shape the allies you have tomorrow.

The tables were set in a Mississippi dining hall in 1943.

Porcelain plates under a Southern sun.

White cups.

Silverware that made a young man stop in his tracks.

Joseph Huber walked into that hall expecting punishment.

He saw those plates.

And in that moment—though he could not have put words to it yet—his life took a turn.

He would spend the rest of his years walking that new road.

From prisoner to doctor.

From enemy to friend.

From a man who’d been told America was a land of decadence and cruelty to a man who knew, from experience, that it was something else entirely:

A place where, once upon a war, someone had chosen to set the tables.

News

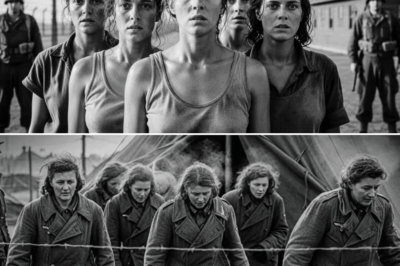

(CH1) “They Didn’t Know What It Was” — German Women POWs Shocked by Their First Period Products

By the time the train from New York jolted to a stop in Pennsylvania, the women had forgotten what stillness…

(CH1) “Don’t Shoot, She’s Pregnant!” — German Women Shocked When American Soldiers LOWERED Their Rifles

By April 1945, the war had already taken almost everything from her. Her name was Lotte, twenty-one years old, eight…

(Ch1) “They’re Stealing My Baby!” — German Woman POW Screams as American Soldiers Take Her Newborn Baby

On the day the train doors finally slid open, the heat hit her like a hand. Margarete Wolf blinked into…

(CH1) “Line Up Outside!” – German Women POWs Were Shocked by the Order of American Soldiers

The first whistle cut through the dawn like a blade. It was just after five on April 29th, 1945, and…

At the Briefing, My Brother Mocked “You’re Not a Real Pilot,” Until the General Saluted Raptor Six… Ever had a moment where someone doubted your worth right to your face?

I didn’t hear the first laugh. I heard the second one. The one that breaks just a little louder than…

I WAS IN THE ICU—BLEEDING, BARELY CONSCIOUS AFTER A BRUTAL CRASH. THE DOCTOR SAID THEY NEEDED FAMILY TO APPROVE EMERGENCY SURGERY. MY MOM SAID FIVE WORDS: “CAN’T COME. YOUR BROTHER’S PROMOTION PARTY.” THEY CHOSE A PARTY OVER MY LIFE.

I didn’t hear the sound of my own car hitting the guardrail. I remember the scream of someone else’s brakes,…

End of content

No more pages to load