Story title: Paper Walls

March 1946

Fifteen miles south of Fort Dix, New Jersey

The morning came in wrapped tight, like the army didn’t want anyone seeing too clearly.

Fog swallowed the fence line, turned the barracks into gray ghosts. The low processing building stank of wet concrete and industrial soap—clean, but in an unforgiving way.

Eighty-three German women stood inside, lined up in rows that stretched the length of the room.

They’d crossed the Atlantic in silence three days earlier. No brass bands on the dock, no speeches. Just boots on gangplanks and the creak of a ship that had carried too many troops east and was now bringing the leftovers back west.

The war had been over ten months, but its paperwork was still catching up.

Corporal James Brennan leaned by the door, clipboard pressed against his chest like armor, and watched the women file past the intake desks.

He was twenty-four, from a town in upstate New York so small it didn’t make it onto most maps. His war had been fought with carbon paper and staplers, a typewriter instead of a rifle. He’d spent D-Day checking manifests instead of wading through surf. Sometimes he felt guilty about that. Mostly he didn’t. Someone had to keep the chaos from eating itself.

He’d processed hundreds of German prisoners since the previous summer. Men with hollow cheeks and hard eyes, some defiant, some resigned, some trying not to be terrified.

These women were different.

They looked like their male counterparts in some ways—thin, hunched deeper into themselves than any manual could fix. Uniforms hung on them, the field-gray cloth too big for the shrinking bodies inside. Their hair was clean now—the ship had had showers—but dull, cut short in rough, practical styles.

Their eyes moved constantly.

Tracking exits.

Counting guards.

Calculating odds they’d never say out loud.

One woman in the middle of the line caught his attention.

Not because she was pretty—she might have been, somewhere under the sharpness war had carved into her features—but because she was still.

Perfectly still.

Everyone else shifted. Adjusted collars, rubbed hands over arms, rocked from foot to foot. The buzz of nerves ran up and down the lines.

She stood with her shoulders back, chin level, hands clasped loosely in front of her. Posture straight as a yardstick. Her face was blank in a way that didn’t read as empty—more like carefully shuttered.

There was something about that stillness that spoke to Brennan. Discipline. Endurance. Or maybe just stubbornness.

He glanced at the intake sheet on his clipboard, where names blurred.

He’d find out which one was hers.

Eventually.

“Next,” Captain Gershwin barked from the intake desk, his Brooklyn accent thick enough to chew.

A woman stepped up, heels clicking softly on the concrete.

“Name?” Gershwin asked.

“Monika Bauer,” she said in careful English.

“Rank? Assignment? Service dates?”

The script was the same as always. Name. Rank. Role. When did you join. Any wounds. Any illnesses. Next of kin.

Her answers dropped into the form like stones into deep water. Each was copied in triplicate, stamped, slid into a pile that would eventually find its way into some filing cabinet in some warehouse and sit there until mold or historians got to it.

The machine of bureaucracy rolled on.

Brennan’s job was to be the conveyor belt.

Groups of twenty women at a time went from intake to medical, from medical to temporary housing. He walked ahead, herd dog in olive drab, making sure no one lagged behind, no one slipped away, no one collapsed.

It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t what war movies were made of. But it required patience and a steadiness that he’d always had.

“Next twenty,” Gershwin called.

The still woman moved with that group.

Brennan turned.

“This way,” he said in German that was rough but understood—three months of evening classes, a dog-eared phrase book, and practice on reluctant male prisoners.

“Folgen Sie mir. Follow me.”

They walked down a corridor painted a greenish-gray that might have once been called “sage” by someone with more imagination. Now it just looked like institutional despair. Bare bulbs buzzed overhead.

In the medical room, army nurses waited in crisp white uniforms, faces professional and tired.

“Strip to the waist,” one of them said. “Step forward. Next.”

They checked for lice. For scabies. For TB. For anything that might spread through a camp like wildfire.

The still woman unbuttoned her jacket with precise motions, folded it over her arm, and submitted to the examination without comment. The nurse listened to her lungs, checked her lymph nodes, asked if she had any complaints.

She shook her head once.

The nurse marked “none” in the file and moved on.

Brennan led them to the barracks next.

The long wooden building had been scrubbed recently but retained the smell of old sweat, damp wool, and pine. Bunks lined both walls, thin mattresses on metal frames, gray blankets folded at the foot of each.

It wasn’t home. It wasn’t comfort.

It was dry and warmer than outside.

The women hesitated at the threshold. Some seemed surprised there were beds at all.

“You can choose any bunk,” Brennan said in slow German. “Ihr könnt jedes Bett nehmen.”

They moved cautiously inside, as if someone might shout at them that they’d chosen wrong.

He stood at the door, watching.

His orders were clear. No rough treatment. No harassment. These were prisoners, yes, but prisoners under American custody, which meant Geneva Conventions. It meant rules.

It was supposed to mean something.

When they’d all found places, he cleared his throat.

“Das Essen kommt um zwölf Uhr,” he said. “Food at twelve. Wasser ist im Waschraum—water in the washroom. If you need a doctor, say it to the guard. Ein Arzt. Do you understand?”

He searched for one more phrase. One he wasn’t sure existed in the right form.

“Ihr seid… sicher hier,” he said.

You are safe here.

They looked at him.

One woman—a thin thing with a scar running from the corner of her mouth up toward her ear—let out a bitter laugh.

Another looked away, jaw tightening.

The still woman met his gaze.

Her eyes were gray, the cold kind, like winter skies over the Hudson.

There was a question in them.

He didn’t know what it was.

He nodded anyway, as if answering.

Then he stepped back out into the corridor, letting the door swing shut.

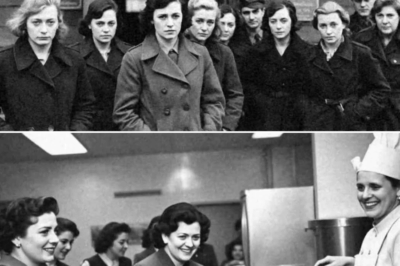

At noon, the mess hall filled with the usual sounds—metal trays clattering, boots on concrete, the low rumble of soldiers’ conversations.

The German women filed in wearing their issued camp clothing, field-gray swapped for faded American khaki with “P.W.” stenciled on the back.

They held trays stiffly, two hands, knuckles white.

Ahead, the cooks ladled mashed potatoes, spooned canned green beans, plopped slabs of meatloaf that had started the day frozen solid. Bread with a scrape of butter. Coffee poured from dented urns into tin cups.

Army food.

Nobody would write home about it.

But it was hot. There was enough of it. No one was counting calories like they were coins.

Some of the women ate fast, shoulders hunched, eyes flicking sideways as if someone might snatch their plates.

Others took their time, almost reverent, chewing each bite as if their bodies didn’t quite trust that more was coming next.

The still woman—Brennan still didn’t know her name—ate methodically. Small bites. Slow. Coffee in measured sips. Nothing wasted. Nothing rushed.

He watched from a small table near the wall, his own tray half-finished.

He didn’t know why he kept finding her in a crowd. Eighty-three women, each with stories carved into their faces, and his attention kept sliding toward the one who barely moved.

She didn’t look broken. Not like some of the others, whose eyes had that glassy, too-bright look of people ready to fall over an edge.

She looked… contained.

Like she’d built a wall around whatever hurt, and was holding it up with sheer will.

He knew something about walls.

His just looked like filing cabinets.

Orientation that afternoon took place in the same mess hall, tables pushed back, chairs scraped into rows.

Major Holloway—square jaw, voice like a parade-ground bullhorn—stood at the front with a piece of paper in his hand.

The interpreter, a German-American sergeant, stood beside him.

“You are prisoners of war under the custody of the United States Army,” Holloway read. “You will be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions.”

The interpreter relayed each sentence.

“You will be assigned work details. You will be paid a small wage. You will be housed, fed, and provided with medical care. Refusal to cooperate will result in disciplinary action, but physical punishment is prohibited.”

He lowered the paper, eyes sweeping the room.

“This war is over,” he said, voice softer now. “You lost. We won. That’s the simple truth.”

Murmurs shifted through the women, most faces unreadable.

“But that doesn’t mean we’re going to treat you like garbage,” he continued. “You’re going to work. You’re going to earn your keep. But you’re going to do it as human beings. With dignity. In return, you’ll be treated with the same. Understood?”

The interpreter translated.

A few women nodded.

Most just stared.

The still woman’s mouth twitched. Not quite a smile. Not quite disbelief.

It was the first crack in her armor Brennan had seen.

Work assignments came the next week.

Teams of officers sat with charts, slotting women into categories.

Strong enough for farm work?

Skilled enough for factory work?

Trained for nursing?

Too sick for hard labor?

The still woman’s name appeared on a roster Brennan picked up Monday morning.

Kramer, Analise. Age 26. Former: Fernsprechgehilfin — telephone operator. From near Munich.

She’d gotten the garment factory detail in Trenton.

So had fifteen others.

The manual said each work detail needed an escort who could keep order, keep time, keep everyone alive between camp and job.

They gave it to Brennan.

“Congratulations,” Gershwin said wryly. “You’re now officially a bus driver with a gun.”

The truck they used for transport was a half-ton with wooden benches and a canvas cover that flapped when the wind hit right.

Every morning at 0600, Brennan stood by the back, checking names off as the women climbed in.

“Kramer, Analise,” he called.

“Hier,” she answered, voice dry.

She climbed up, sat near the back, posture straight, hands in her lap.

Every evening at 1700, he drove them back through the streets of Trenton, past brick row houses and corner grocers and kids playing stickball, and backed up to the camp gate.

The routine settled around them all like a blanket.

The factory belonged to a man named Lieberwitz.

He was short, thinning hair, a permanent frown. His accent carried Warsaw and years of survival. He’d fled in ’38, leaving behind parents and sisters who hadn’t made it out.

He looked at the German women the first day with eyes that held a ledger only he could see.

“Seams straight,” he said through the interpreter. “Stitches tight. No wasted material. No mistakes.”

He put them at long tables with bolts of cloth and spools of thread, and the women’s hands went to work.

If war had taught them anything, it was how to do repetitive tasks without complaint.

Analise took a place at the far end of one table.

Her fingers moved quickly, sure. She measured, cut, sewed, her stitches even and neat. Brennan could see, even from his post by the door, that she treated every hem like it mattered.

He sat in a chair near the entry, rifle against the wall, book in his hands.

The Grapes of Wrath.

Dust Bowl refugees and migrant camps and people being treated like numbers instead of names. It felt appropriate.

Sometimes he looked up and saw Analise watching him.

When their eyes met, she didn’t flinch.

She just looked.

Then turned back to her work.

As if deciding he wasn’t worth the energy.

It bothered him more than it should have.

One gray afternoon, the truck coughed halfway back to camp.

Then coughed again.

Then died.

Brennan coasted it onto the shoulder and let out a string of curses that would have made his mother blanch.

The women sat in the back, silent bundles in army coats.

He popped the hood, stared at the maze of pipes and bolts like it was some enemy code he’d never been trained to crack.

From behind him, a voice said in accented English, “Es ist die Benzinleitung.”

He turned.

Analise stood at the tailgate, arms folded.

“The what?” he asked.

“Fuel line,” she said. “It is loose. Or cracked. The engine… gets no fuel.”

He blinked.

“You know engines?” he asked.

“My father had a Werkstatt,” she said. “Garage. I grow up with oil on my shoes.”

He looked from her to the engine and back.

“Can you fix it?” he asked.

She hesitated, just for a second.

“If you have tools,” she said.

He reached under the seat, pulled out the small toolbox everyone pretended wasn’t officially there.

He handed it up.

She took it and climbed down.

The other women watched, curious.

Analise approached the engine like she approached everything—calm, measured. She leaned in, fingers probing lines, clamps, connections.

She tightened a bolt. Adjusted a hose. Wiped her hand on her skirt.

“Try now,” she said.

He slid back into the cab, turned the key.

The engine coughed once.

Then roared.

He stared at the dashboard, then at her, relief and something like admiration tangled in his chest.

“How did you know?” he asked.

She shut the hood.

“Erfahrung,” she said. “Experience.”

She handed him back the toolbox, climbed into the truck again, and sat down.

He drove the rest of the way in silence.

That night, in his bunk, he kept seeing her hands in the engine bay, sure and competent.

She had more in her than the line in the file said.

Of course she did.

Everyone did.

That was the point, he reminded himself. Why he did what he did. Why he’d been glad not to be issued a rifle.

People were more than what uniforms they’d been shoved into.

He believed that.

He had to.

Time did what it always did.

It moved.

Spring in New Jersey came with skepticism—warm for a day, then cold enough to remind you who was in charge. Mud, then buds, then suddenly the world went green.

The women adjusted.

They learned when the guards did bed checks, which cooks were generous with coffee, and how far they could bend the rules without breaking them.

Some started talking more, jokes whispered down the line, laughter that sounded surprised.

Analise stayed in the space between silence and chatter.

She spoke when she needed to.

She answered questions.

She didn’t volunteer much.

Brennan found himself manufacturing reasons to talk to her, small ones at first.

“Wie war die Arbeit heute?” How was work today?

“Gut.” Good.

“Do you need more thread at your station?”

“Nein.”

He learned that she’d been from a town near Munich.

That her father had died before the war.

That her mother and younger brother were somewhere in what was left of Bavaria.

Or had been, last she heard.

He learned it in fragments.

She learned that he came from a place called Camden Falls, that his father sold hardware and his mother taught school, that he had two sisters who wrote him letters full of gossip and recipes he couldn’t use.

She did not ask for more than that.

Little by little, the routine wove them all together.

One afternoon in May, a woman named Greta—different Greta, not any of the other Gretas the war seemed to produce—slumped forward at her sewing station.

The thud of her head hitting the table snapped the room’s rhythm.

For a heartbeat, no one moved.

Brennan was across the floor before his brain caught up, kneeling beside her, fingers at her throat.

Pulse. Fast. Weak.

“Medic!” he shouted, already trying to remember the German words. “Sanitäter!”

The nearest guard sprinted for the truck radio.

Analise appeared as if summoned, pushing past the other women.

She knelt opposite him, her face going calm in the way people’s did when they’d seen too much panic already.

“Sie ist…?” she asked.

“Alive,” he said. “But—”

“Malnähr,” she cut in. Malnourished. “And müde. Tired. She needs Arzt. Doctor.”

The medic arrived, bag clanking.

He examined Greta quickly. Pupils, pulse, breathing.

“Anemia,” he said. “Exhaustion. Get her to infirmary.”

As they lifted Greta onto a stretcher, Brennan caught the way Analise watched him.

Something in her gaze had changed.

A notch softer.

As if the file in her head about him had gained a line: Runs when someone falls.

The women’s pay came weekly.

Small coin envelopes with names penciled on the front and ten-cent-an-hour reality inside.

They lined up to collect them, fingers flipping lids, eyes counting coins.

Some tucked the money into shoes, sewn pockets, rolled into bras.

Analise took hers back to the barracks.

Brennan saw her one evening when he was doing a walkthrough, checking for contraband and major issues.

She sat on her bunk, wooden box open on her lap.

She slid the envelope in, alongside neat stacks of others.

He didn’t comment.

Just watched a second too long.

She noticed.

“Für später,” she said, almost defensively.

“For later.”

“For what?” he asked, before he could stop himself.

She closed the lid.

“I don’t know yet,” she said. “But I will.”

The Fourth of July snuck up on him.

He’d lost track of dates.

Camp command didn’t.

If there was a holiday, they’d find a way to observe it.

No fireworks this year. No parades.

Just a cookout on a patch of grass behind the mess hall, barrels cut in half to make grills, soldiers flipping hot dogs, lemonade pitchers sweating in the heat.

The women were allowed to come.

“Restricted area,” Gershwin had said. “But let ’em see we’re not ogres.”

They stood in clusters at the edge of the gathering, unsure.

The Americans played horseshoes. Someone produced a baseball and a bat. A radio played swing music under the static.

Brennan snagged two paper cups of lemonade and threaded through the crowd.

Analise stood alone, arms folded, watching.

He offered her a cup.

She eyed it.

“What is?” she asked.

“Limonade,” he said. “Tradition.”

She took a cautious sip.

Made a face.

“Sehr süß,” she said. “Very sweet.”

“Yeah,” he chuckled. “That’s the other tradition. Sugar.”

They watched the soldiers laugh, someone attempting to teach a Bavarian girl how to throw a curveball with much gesturing.

“You celebrate your freedom,” she said quietly after a minute.

He glanced at her.

“We do,” he admitted.

“We remember ours is gone,” she said.

He didn’t have an answer for that one.

They drank in silence.

Sometimes that was better than anything he could say.

Summer turned the barracks into ovens.

Fans rattled in windows. The women’s hair stuck to their necks. Sweat darkened the backs of khaki shirts in damp Vs.

At the factory, the air hung heavy with heat and fabric dust. They worked in shifts, breaks staggered to avoid anyone dropping from heat stroke.

Brennan made sure water jugs were filled. That was within his power.

He made sure the fans worked and that when they didn’t, he yelled up the chain until someone fixed them.

He made sure Lieberwitz didn’t push the women past reason.

“He works them hard,” Brennan told Gershwin once, “but he pays fair. And he could have asked for anyone. He asked for them. I think that counts.”

“Don’t go soft on me, Brennan,” Gershwin said, but there was no bite to it.

The women noticed.

They began to bring questions to him that had nothing to do with daily schedules.

“Where can we send letters?”

“Can we go to church?”

“Are there German newspapers?”

He answered what he could.

Sometimes that meant “I don’t know.”

He discovered that admitting ignorance actually made them trust him more.

Honesty was a rare commodity in any war.

Apparently it worked after one, too.

One August evening, as the truck’s engine ticked as it cooled inside the gate, Brennan tossed his clipboard onto the seat and glanced back.

The women had all climbed down and were walking toward the barracks.

All except one.

Analise sat on the bench, hands folded, staring at nothing.

He walked around to the back and leaned against the tailgate.

“You okay?” he asked.

She was quiet a long time.

Then she said, very softly, “My brother wrote.”

He straightened.

“The one in Germany?” he asked.

She nodded.

“In a camp near Nuremberg. Not… Lager like your films. Lager for displaced persons. No work. No home. Stadt.” She groped for the English. “City is… rubble and ghosts.”

He had no words.

“I’m sorry” felt useless.

“What will you do?” he asked instead.

She laughed once, without humor.

“What can I do?” she said. “I am here. He is there. I have ten cents an hour and a bed in a camp. I cannot go to him. I cannot bring him here.”

He had nothing to offer but presence.

So he sat.

They watched mosquitoes dance in the humid air until the first stars came out.

It wasn’t enough.

But it was something.

By September, the work detail had become a fixture in the factory.

Lieberwitz called Brennan into his office one afternoon, shutting the door behind them.

“I got a contract,” he said. “Navy. More uniforms. More work.”

“Congratulations,” Brennan said.

“I need more hands,” Lieberwitz went on. “Good hands. I want to hire some of your girls full-time when they’re released. Pay them real wages. They’re good workers.”

He shrugged.

“I know what they were,” he said. “I know what that uniform meant. But I see what they are now, too. I can use that.”

“Do you think they’ll stay?” he asked.

Brennan thought of Analise’s carefully folded pay envelopes, of Gretel fainting at her sewing station, of letters describing rubble.

“Some of them might not have anywhere else to go,” he said.

“Ask,” Lieberwitz said. “Tell them it’s work, not charity. They earn, I pay. Simple.”

The women listened to the offer in the barracks that night with faces that ranged from hopeful to suspicious.

Some said no immediately. They wanted to go home, whatever that meant now.

Others said maybe.

Analise said nothing.

When the others had drifted toward their bunks, she approached Brennan.

“This offer,” she said, “it is real?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Liev’s a tough old bastard, but he’s straight. He’ll expect a lot. But he’ll pay. And once you’re civilian, you can live in town. No more wire.”

She looked at her hands.

“If I stay,” she said, “I cannot go home.”

“No,” he admitted. “Not for a while.”

“But I can send more money,” she said slowly. “For meine Mutter. My brother.”

He nodded.

“And maybe someday,” he added, “they can come here. It’s hard. But not impossible.”

She met his eyes.

“You think this is possible?” she asked.

He thought of her at the truck engine, of her fixing what he couldn’t, of the way she’d grabbed Greta’s collar when she’d fainted.

“I think,” he said carefully, “you can do whatever you set your mind to. And if anyone can make the impossible budge, it’s you.”

She was quiet.

“I will think,” she said.

January 1947

Snow fell in thick, wet flakes that stuck to the chain link and softened the hard lines of the camp.

Analise walked out of the processing center carrying one small bag. Inside were her clothes, the book of German poetry Brennan had given her for Christmas, and the wooden box with her pay envelopes.

Her prisoner tag had been cut off.

She was officially a civilian now.

No more daily roll call.

No more headcounts.

She headed for the road that would take her toward Trenton and the boarding house near the factory.

Brennan was waiting at the gate.

He didn’t have to be.

Technically, his responsibility ended once her paperwork was stamped “released.”

But there he was, hands in his pockets, breath steaming.

“You made it,” he said.

“Yes,” she replied.

They stood there, suddenly awkward, stripped of the roles that had defined them for a year.

He gestured toward the road.

“I’ll walk you,” he said.

She could have said no.

She didn’t.

On the steps of the boarding house—a brick building with peeling paint and curtains that didn’t quite match—she set her bag down.

“This is home now,” she said, not sure if it was a question or a statement.

“For a while,” he said. “Till you figure out the next step. Or decide this is enough.”

He shifted his weight.

“You’ll do fine,” he said. “At the factory. Liev likes you. And you…”

“And I?” she asked.

He swallowed.

“You remind me,” he said slowly, “that people are more than the worst thing on their record.”

Her brows knit.

“That is dangerous thing to believe,” she said.

“Maybe,” he said. “But it’s the only way I know how to be.”

She looked at him for a long time.

Then, very quietly, she said, “Good. Because I think I like you, James Brennan. And that is also dangerous.”

His heart took off like a startled bird.

“Maybe,” he said again. “Guess we’ll have to see how dangerous.”

She picked up her bag and went inside.

He stood on the sidewalk long after the door closed, staring at the brick, feeling something he hadn’t felt in a long time:

Hope.

The next year unfolded in small, careful steps.

Brennan left the army that spring when his enlistment ended. He enrolled at Rider College on the GI Bill, took a part-time job at a law office in Trenton—filing, answering phones, doing the kind of paperwork he’d been doing in uniform, just in a suit now.

Analise worked at the factory full-time.

Lieberwitz made good on his promise. He assigned her to quality control, then to training, then to floor supervisor when it became clear she could spot mistakes faster than anyone else and fix them with a look.

They saw each other twice a week.

Coffee at a diner near the bus stop.

A walk in a park on Sunday afternoons.

They talked about little things at first. Weather. Bus schedules. How American bread tasted like cake.

Then bigger things.

Her father’s garage.

His hometown and why he had no desire to go back there.

Her mother’s letters from a Bavaria slowly clawing its way back from nothing.

The war, when they could.

The future, when they dared.

People looked, of course.

An American with a German.

Even in ’47, even in a country already pivoting to new enemies, the old lines hadn’t faded completely.

Some stared. Some muttered.

Most were just tired.

Sometimes the waitress would top off their coffee and say, “You two are my favorite regulars,” with a smile that told them which side she’d chosen.

One rainy February evening, Brennan wrapped both hands around his cup and said, “I’ve been thinking about getting out of the Army, going to school. Sticking around here. In Trenton.”

“So you can see more factories?” she teased.

“So I can see more coffee shops,” he said. “And the people in them.”

She understood.

“It would be… gut,” she said.

Good.

Her thumb brushed against his on the Formica tabletop and stayed there for a heartbeat longer than necessary.

That summer, a letter came from Germany.

Her mother was dying.

Cancer, they thought. No treatment. No real medicine. Just pain and waiting.

Annalise sat on the steps of the boarding house, letter crumpled in her fist, eyes hollow.

“I should go,” she said. “But if I go, I may not come back. And if I stay…” She didn’t have to finish.

Brennan didn’t offer false solutions.

He went to the bank, withdrew most of his savings, and placed an envelope in her hand the next day.

“Send it home,” he said.

She stared.

“No,” she protested. “This is… you need—”

“I can earn more,” he said. “You only get one Mutter.”

She cried.

Not polite tears. Not the contained kind he’d seen in the barracks.

She kissed him for the first time that night.

Sudden.

Fierce.

It felt like a door slamming open.

“I love you,” he said when they came up for air, the words tumbling out like they’d been waiting on the tip of his tongue.

“You shouldn’t,” she said automatically, echoing every voice in her head.

“Too late,” he replied.

“I love you too,” she whispered. “Gott helfe mir.”

God help me.

Her mother lived three more months.

The money paid for painkillers and a doctor who came twice a week instead of once a month.

When the woman died in October, Greta mourned from across an ocean, grief filtered through paper and ink.

Brennan sat beside her on those nights, her head on his shoulder, his shirt wet, and learned that sometimes loving someone meant letting them hurt without trying to wrap bandages around feelings you couldn’t fix.

In November, over overly sweet coffee and a slice of pie at their usual booth, she said, “I have been thinking.”

“Dangerous,” he said.

She smiled.

“I think,” she continued, “if you asked me to marry you, I would say yes.”

He blinked.

“That a proposal?” he asked.

“No.” Her eyes sparkled. “That is… information.”

He laughed, nervous and exhilarated all at once.

“Well then,” he said, reaching across the table to take her hands, “let me act on that information.”

“Analise Kramer,” he said, voice shaking, “will you marry me?”

She looked at him for a long moment.

“Ja,” she said softly. “Yes. I will.”

The waitress, Dorothy, clapped from the coffee machine.

“About damn time,” she said, bringing over two slices of pie with extra whipped cream. “On the house.”

His parents hated it.

In letters that bled disappointment between the lines, his mother wrote about “our boys dying over there” and “bringing one of them here.” His father called it a mistake.

He wrote back that he loved them, but he was marrying Analise with or without their blessing. They were welcome to come.

They didn’t.

Her brother wrote that he was happy for her, that she deserved joy after everything. He couldn’t come either, but his words meant more than a presence would have.

They married in February 1948 in a small chapel near the college.

The chaplain from the camp, who still had his German hymnal, officiated. Friends from Rider and the factory came. Dorothy brought coffee. Lieberwitz brought a check big enough to make Brennan’s eyes water.

“Don’t argue,” the factory owner said gruffly. “You two earned it.”

She wore a dress she’d sewn herself.

He wore his only suit.

They exchanged vows twice—once in English, once in German.

“I take you as my wife,” he said.

“Ich nehme dich zu meinem Mann,” she replied.

They kissed.

The world did not explode.

It just shifted, a half inch to the better.

The years after that weren’t perfect.

They were just life.

Rent to pay. Class schedules to juggle. Nightmares that still pulled Analise out of sleep some nights, breath coming in gasps, German words spilling out, the camp wire standing in for every fence she’d ever feared.

He held her through them.

She let him.

He graduated, took a permanent job at the law office. She moved from sewing to supervising, then eventually left the factory to raise their kids and work with refugees, helping people whose stories felt too familiar.

They bought a house.

Small. Two bedrooms. One tree in the yard.

It was more than enough.

Neighbors took time.

Some stayed distant.

Some brought casseroles.

Some glared at first, then, after hurricanes and block parties and PTA meetings, leaned over the shared fence to ask for sugar and offer gossip.

Her past never went away.

It just took up less space as her present expanded.

When their daughter asked, years later, “Who were you in the war, Mama?” Analise didn’t lie.

“I wore the wrong uniform,” she said. “I answered phones for the wrong people. I believed what I was told. I was wrong. And I have tried every day since to live differently.”

When their son debated enlisting, she flinched.

When he did enlist, she hugged him tight and sent him off anyway.

When he came back from his own war wanting to marry a German girl he’d met overseas, she just laughed.

“Full circle,” Brennan said.

“Yes,” she replied. “This time, maybe, we break the circle instead.”

In 1985, when their grandkids asked how they’d met—really met, not the sanitized “we worked together” version—Brennan would tell them about a foggy morning in a processing center south of Fort Dix.

He’d talk about lines of women, about a still figure in the middle of the chaos, about a truck that broke down and a fuel line fixed by capable hands.

Analise would talk about a guard who spoke bad German and good truths, who treated her like a person when he didn’t have to.

They’d both talk about coffee.

About saying yes when saying no might have seemed safer.

About building something out of paper and stitches and second chances.

War histories wouldn’t mention them.

They didn’t change the map.

They didn’t topple governments.

But in a small house in New Jersey, two people who’d once stood on opposite sides of a ruined world held hands on their back step, watching the sun go down over a neighborhood that had never known occupation.

“Do you regret it?” Brennan asked once, out of nowhere, an old man’s question to the woman he’d known in three different versions.

“No,” she said. “Do you?”

He squeezed her fingers.

“Not for a second.”

She smiled, lines deepening around eyes that had seen too much and somehow stayed kind.

“Good,” she said. “Then all that paperwork was worth it.”

He laughed.

“Somebody had to keep the record straight,” he said.

“And someone had to decide when to write a different story,” she replied.

They’d done both.

It was enough.

THE END

News

Amidst the chaos, they set up a makeshift aid station in a church displaying a prominent red cross, treating wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict.

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

German “Comfort Girl” POWs Were Astonished When American Soldiers Respected Their Privacy

The Day the Monsters Had Rules Schroenhausen, Bavaria April 1945 The engines came first. Margaret Miller pressed her forehead to…

My husband left us for his mistress—and three years later, I met them again. It was unbelievable, but satisfying.

After 14 years of marriage, two children, and a life I thought was happy, everything collapsed in an instant. How…

The Dishwasher Girl Took Leftovers from the Restaurant — They Laughed, Until the Hidden Camera Revealed the Truth

Olivia slid the last dish from a large pile into the sanitizer and breathed a sigh of relief. She wiped…

German Women POWs in Oklahoma Were Told to Shower With Water — And Burst Into Tears

Story title: The Day the War Fell Off Their Skin Camp Gruber, Oklahoma April 1945 The truck came in on…

“Are There Left Overs?” Female German POWs Were ASTONISHED When They First Tasted Biscuits and Gravy

Story title: Biscuits and Mercy Camp Somewhere in the American Midwest Late 1944 The first thing they noticed was the…

End of content

No more pages to load