Story title: The Day They Cried for Soap

Camp Gruber, Oklahoma

April 1945

The transport truck came in under a bright, indifferent sky.

Dust boiled up behind its tires as it rattled along the gravel road toward the processing compound, the smell of exhaust mixing with the faint scent of red Oklahoma dirt.

Captain Sarah Henderson of the Women’s Army Corps shaded her eyes and watched it come.

She’d seen plenty of trucks like this in the last year. Loaded with German prisoners—tired, sullen men in field-gray uniforms, marched off ships and trains to this strange patch of prairie they’d never heard of.

She thought she knew what to expect.

“You got a new batch for me, Captain?” called Dr. James Morrison from the infirmary steps, white coat catching the sun.

“Looks like it,” Sarah called back. “Try not to scare them too much.”

He snorted. “I’ll save that for the inoculations.”

The truck lurched to a stop.

The back doors swung open with a metallic screech.

Forty-three German women climbed down.

Sarah’s breath caught.

They were in uniform, yes—field-gray skirts, tunics, insignia. The ages stamped on their faces ranged from young—nineteen, twenty—to women old enough to be her mother. Nurses, radio operators, clerks. She’d read the manifest that morning.

What she hadn’t expected was how… diminished they looked.

She’d seen hungry people before. Soldiers at the front toward the end of a campaign. Civilians in London after the Blitz.

This was different.

Their uniforms hung on them like costumes on wrong-sized mannequins—fabric swallowing limbs that were little more than bone and tendon. Cheeks hollowed out so much their eyes seemed too large, sunk deep into sockets like dark marbles.

Skin the color of old wax. Hair dull, broken, lifeless.

Several limped as they climbed down, wincing with each step. Two had to be helped by others, arms looped under theirs just to keep them upright.

But the smell was what hit Sarah hardest.

Even from twenty feet away, the odor rolled over her—sweat, grime, unwashed skin, something sour and tired and defeated. It was a smell she knew from front-line troops who’d been in foxholes too long.

This was worse.

She realized, with a start, that some of these women might not have had access to a real bath in months.

“Captain?” Sergeant Mary Kowalski—compact, sharp-eyed, with dark hair in a regulation bun—stepped up beside her. “You want me to get them lined up?”

“Yeah,” Sarah said, pushing the shock down where it wouldn’t show. “Standard formation. We’ll run them through medical, dousing, showers, clothing, barracks. Same as usual.”

“Jawohl,” Mary said with a wry smirk, then raised her voice. “Stellen Sie sich in einer Reihe auf! Here—line up!”

The women shuffled into place, boots scuffing the gravel.

Sarah scanned their faces for the usual things.

Fear. Defiance. Sullen resignation.

She saw fear, yes.

But underneath it, she saw something she didn’t recognize—a kind of brittle hope, mixed with disbelief. As if they were on the edge of allowing themselves to think something might not be as bad as they’d been told, but were afraid to lean on that thought in case it broke.

She cleared her throat.

“Sergeant,” she said. “Let’s give them the standard spiel. Medical exam, showers, clean clothes, barracks.”

Mary nodded and turned to the women.

“Sie werden zuerst ärztlich untersucht,” she called. “Dann gehen Sie zu den Duschen. Dort bekommen Sie Seife und saubere Kleidung.”

You’ll get a medical exam, then you’ll go to the showers. You’ll get soap and clean clothing.

The reaction was immediate.

Sarah expected maybe a few relieved expressions. A sag of shoulders.

Instead, several women simply… broke.

Not quiet tears.

Not the discreet dabbing at eyes she’d seen from officers stripped of their rank.

Deep, shaking sobs tore out of them, bending them at the waist. Some dropped where they stood, knees hitting gravel. Others clutched at the sleeves of the women next to them, as if the ground had tilted and they needed anchoring.

One woman, mid-twenties maybe, with a face that might once have been pretty before war had carved hard lines into it, stared at Mary like she’d just announced they were handing out gold.

“Seife?” she whispered. “Echte Seife? Sie geben uns Seife?”

Soap? Real soap? You’re giving us soap?

Mary blinked, thrown.

She glanced at Sarah, eyebrows up.

“I told them… showers, soap, clothes,” she said under her breath. “Like we always do. I don’t—”

“Confirm it,” Sarah said quietly, throat tight. “Maybe they didn’t hear you right.”

Mary turned back.

“Ja,” she said, slowly. “Echte Seife. Zum Waschen. You will be able to wash yourselves. With real soap.”

The woman’s legs gave out.

She hit her knees as if pulled by gravity, hands over her face. A sound came out of her that Sarah would later, when she tried to describe it, call a keening. Not pretty. Not controlled. Raw.

The sound caught like a spark in dry tinder.

Half the line crumpled.

Some cried as violently as the first, bodies racked with sobs that looked painful in their intensity. Others just stood there, faces blank, tears sliding down without expression, as if their minds had simply stepped aside.

A few clung to each other, foreheads pressed together, small islands of physical contact in a sea of unraveling.

“What in—” Sarah started, then caught herself.

“Doctor!” she snapped, turning. “Morrison, front and center, please.”

He jogged over, eyes narrowing as he took in the scene.

“Mass hysteria?” he murmured. “What did you say to them, Kowalski, ‘welcome to the gas chamber’?”

Mary shot him a look.

“I told them we were going to give them a shower and soap,” she said. “Like always.”

Morrison watched a moment longer, physician’s gaze cataloguing details.

“No one’s seizing,” he said. “No one’s hyperventilating to the point of passing out. This isn’t a seizure event. It’s…” he shook his head slightly. “It’s… something else.”

He turned to Mary.

“Ask them why,” he said. “Ask what soap means to them.”

Mary waded into the line, speaking quietly to the women. Snatches of German and English drifted back.

“…kein Seife… ein Jahr…”

“…nur kaltes Wasser, wenn überhaupt…”

“…wir stinken… wie Tiere…”

They hadn’t had real soap in over a year.

What they’d gotten instead, when they got anything, was a gray-brown brick that barely produced a lather and made their skin itch. By early 1945, even that had vanished. Water itself had become uncertain.

“We cleaned ourselves with… sand,” one woman told Mary in halting German, scrubbing at her own arms as if feeling phantom grit. “Sand and cold water when there was water. We could smell ourselves. We could not… stop smelling ourselves.”

The shame in her voice was almost a physical thing.

Greta—the nurse—stepped forward, wiping her eyes.

“I worked in hospitals,” she said. “In the east. At first, we had supplies. Then… nothing. No bandages, no medicine. No Seife. We watched patients lie in filth we could not clean. Watched ourselves become…” she groped for the English word and settled on the German. “Unmenschlich. Not human.”

She took a shuddering breath.

“They told us you would torture us,” she went on. “They told us Americans would treat us worse than animals. No mercy. No… dignity. And you say… hot water. Seife. Towels.” Her mouth twisted around the unfamiliar word. “Soap. I did not believe such things still existed. I thought… all was gone.”

Sarah listened.

Military manuals didn’t have a chapter for this.

She knew the processing routine by heart: strip, douse, medical, uniform issue, barracks assignment. Efficient. Sanitary. Clinical.

This wasn’t clinical.

This was… revelation.

She made a decision.

“Sergeant,” Sarah said, voice steady with command now. “Tell them the order of operations has changed. Medical can wait. Showers first. All of them. As long as they need.”

Mary blinked.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said, and turned back to the women. “Zuerst duschen,” she called. “Notarzt kann warten. First, showers. Doctor can wait.”

She hardly got the words out before a fresh wave of tears broke.

This time, some of the Americans cried too.

The shower facility at Camp Gruber was purely functional—concrete floor, bare walls, rows of metal showerheads bolted to pipes. No curtains. No tile mosaics. Just Army-issue plumbing and Army-issue soap stacked on shelves in thick, beige bars.

To the German women walking in, it might as well have been a cathedral.

The female guards—WACs and a few older nurses—stood near the door and along the walls, watchful but deliberately turned away when possible, giving the prisoners privacy.

Greta stood just inside the threshold.

She stared at the bars of soap like they might disappear.

Solid.

Smooth.

Smelling… clean.

She reached out and picked one up.

It was a basic military bar, stamped with a quartermaster’s code, faint whiff of disinfectant under the lye. Nothing special.

She lifted it to her nose anyway.

Breathed in.

Beside her, a woman in her fifties with gray hair scraped back into a bun did the same. Her fingers shook so badly she almost dropped it.

When the first showerheads hissed and hot water poured out in steaming arcs, someone laughed—high and hysterical—and someone else sobbed.

The older woman stepped under the nearest spray fully clothed.

Greta watched, frozen, as the water plastered filthy wool to the contours of her skeletal frame. The woman’s eyes closed. Her mouth opened in a soundless cry.

She just stood there, letting heat soak her from head to toe, as if afraid that if she moved, it would stop.

Greta stepped under another shower.

Heat hit her scalp. Ran down the back of her neck. Soaked the collar of her tunic.

She gasped.

For months, water had been cold when it came at all. A basin. A chipped mug. A hurried splash between air raids.

She peeled off her uniform, fingers fumbling with buttons that had learned to cling to dirt.

Her own body startled her.

Ribs counted themselves out under skin speckled with rashes. Hips jutted. The faint swelling at one ankle—she’d twisted it fleeing one air raid—looked more pronounced naked.

She pressed the bar of soap to her arm.

White suds bloomed.

She scrubbed.

The dirt came away in gray streaks.

So did months of something else—the smell, yes, but also a clinging layer of shame she hadn’t even realized had become a second skin.

Around her, women washed their hair three, four times, laughing and crying in turns as the water ran brown, then clearer. They scrubbed at the backs of their necks, at the spaces between their fingers, at the hollows behind their knees.

Some knelt and washed their feet with a care that bordered on reverence.

Others lathered and re-lathered uniforms before wringing them out and hanging them over pipes, washing them again.

One young woman simply stood under the water, eyes closed, soap forgotten in her hand, tears indistinguishable from the stream that traced down her face.

The guards—Mary among them—stood in their corner and watched, silent.

“God,” Mary whispered finally, voice thick. “We had no idea.”

She thought of the German women she’d processed a year ago—tired, yes, but not like this. She thought of the last months of intelligence briefings, the maps showing advancing lines, the arrows meeting in the center of Europe.

None of that had prepared her for this.

“These aren’t ‘the enemy’ the way we pictured them,” she said to Sarah. “They’re…” She groped for a word. “The same people the Nazis chewed up and spat out like everyone else.”

Sarah swallowed hard.

“You gave us soap when we expected torture,” Greta would write later.

Right now, she just pressed the bar harder against her skin, as if she could scrub away not just dirt, but the stories she’d been told about who waited on the other side of the ocean.

After nearly two hours, the water was turned off in stages.

Fresh towels—coarse but clean—made their way around the room. New camp uniforms were handed out in small stacks. For the first time in months, most of the women pulled on clothing that didn’t cling to them with old sweat.

Then came the examinations.

In the infirmary, under harsh electric lights, Morrison and his team moved methodically.

They measured heights and weights. Took blood pressure. Peered into mouths and ears. Pressed gently on swollen joints.

They found scurvy—bleeding gums, loose teeth. Rickets in younger women—bones soft from vitamin D deficiency. Skin infections from flea bites gone untreated. Lice, of course, but deeper issues too—boils that had never drained properly, fungal infections from damp, unwashed feet.

One woman had a foot that was visibly misshapen.

“She’s been walking on this?” Morrison muttered, frowning, as he ran careful fingers along the bones.

“For weeks,” the translator relayed. “There was no doctor. No hospital left. Only… orders.”

He splinted it properly, jaw set.

That night, he sat at his desk and wrote a report that read more like something out of a nineteenth-century public health investigation than a modern army file.

The physical condition of these prisoners suggests prolonged deprivation beyond what recent combat alone would account for… evidence of collapse of basic civilian infrastructure… hygiene, nutrition, and medical care absent for months… recommend full nutritional rehabilitation and extended care…

He put down his pen, rubbed his eyes, and thought, so this is what the “Reich” leaves its own women with.

In the days that followed, stories came out in bits and pieces.

Around chow tables. In the infirmary. In language classes where English and German tangled and traders like Mary patiently untied them.

“We had no water,” one woman said. “The pipes broke. The city… no one came to fix them. We carried buckets from a river, when we could.”

“No light,” said another. “Bombs knocked out the power. At first, candles. Then nothing. We sat in the dark and listened to the guns.”

“Food…” a third shook her head. “Turnips. Sometimes. Bread when we could trade things. We boiled grass one night. My… my neighbor’s child died from eating something that wasn’t food. We didn’t know. We had no choice.”

To Americans like Henderson and Morrison, who’d grown up in a country that had weathered the Depression but never full societal collapse, the idea that an industrial power could slide so far backward in a few years felt surreal.

Soap had been a luxury item for these women.

Soap.

Not lipstick.

Not silk stockings.

Soap.

And the people who’d been labeled “barbarians” in their propaganda were the ones handing it to them now, wrapped in brown paper stamped “U.S. Army.”

One afternoon, when things were quieter, Greta sought out Mary by the camp fence.

The translator leaned against a post, enjoying five minutes of not being someone’s language bridge.

“Sergeant?” Greta said, halting English. “Darf ich… may I… sprechen?”

“Sure,” Mary said, stepping closer. “Gern. Of course.”

Greta looked down at her hands.

“I fought… the whole war,” she said slowly, “in my head. Believing we… Germany… we are… how do you say… high civilization.” She gestured, reaching up. “Kultur. Music. Poetry.”

“And we…” Mary supplied gently, “the Americans… were the opposite.”

“Yes.” Greta’s mouth twisted. “Barbaren. Primitive. We were told… you live like pigs. No art. No…” She waved vaguely.

She looked up, eyes bright with something like embarrassed anger.

“At the end,” she said, “we had no soap. No food. No medicine. We lived like… animals. Worse. And you—” she pointed toward the barracks “—who we were told were… primitive… gave us hot water. Soap. Bandages.”

She shook her head.

“I do not know what to believe now,” she said quietly. “Everything I was told is… falsch. Wrong. Upside down.”

Mary heard the layers in that: about propaganda, about identity, about how hard it was to hold the idea that your world had lied to you in one hand and a bar of soap in the other.

“I can’t tell you what to believe,” Mary said softly. “But I can tell you this: we’re not perfect. We mess up plenty. We’ve got our own bastards to deal with. But we try. To do better than what we fought.”

She shrugged.

“And giving someone a chance to be clean,” she added, “should be the easiest part of that.”

Greta nodded, throat working.

“You gave us… dignity,” she said. “We expected… torture.”

She hesitated.

“Danke,” she whispered.

Camp Gruber wasn’t the only place where scenes like this played out.

Similar groups of German prisoners—women and men—arrived at camps across the U.S. and Europe in 1945 in the same condition. Medical officers wrote the same kind of reports. Guards saw the same tearful astonishment over small kindnesses.

Soap.

Bread.

A bandage applied without contempt.

But in Gruber, the “soap incident” lodged itself deep in the camp’s memory.

It retold itself at reunions, around kitchen tables, in the way old soldiers do—stories starting with, “Do you remember…?”

Sarah Henderson wrote a memo after her report, more personal than the typical Army file. It went up the chain, clipped to formal recommendations.

These women are not criminals, she wrote. They are victims of the same regime we fought. Treating them decently is not only required by the Geneva Conventions; it reflects who we are. How we handle people who have no power over us says more about our nation than any victory parade.

Some colonel in an office in Washington read it, nodded, and used it to push for slightly better rations and recreation materials in similar camps. Henderson never knew exactly where her words ended up. She just saw slightly less resistance when she asked for extra blankets or books from the USO library.

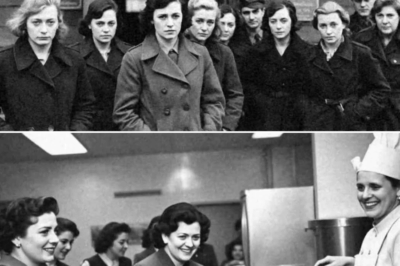

Months later, after VE-Day and VJ-Day and the long process of shipping people home had begun, a letter arrived.

The envelope was thin, the handwriting careful.

From: Greta [last name, mangled by an American clerk].

To: Sgt. Mary Kowalski, Camp Gruber, U.S.A.

Mary found Sarah in the admin office.

“You need to read this,” she said, voice soft as she handed it over.

The English inside was clumsy, every word obviously fought for.

You gave us soap when we expected torture, Greta had written. You gave us dignity when we expected humiliation. You showed us what humanity looks like when it is not twisted by propaganda and hate. I will never forget the moment I stood in that shower room holding real soap in my hands and understanding for the first time that everything I had been told was a lie. Everything I had been taught to believe about America and Americans was wrong.

Thank you for treating us like human beings when we did not expect to be treated as such. Thank you for showing us that civilization still existed in the world.

Sarah read it twice.

Then folded it up and put it in the same notebook where she kept the names of every woman she’d processed that day.

She left the Army in ’46.

Hung up her uniform.

Took a job as a social worker in Tulsa, then later in Oklahoma City, helping people untangle the smaller wars life fought on kitchen tables and in cramped apartments—job loss, illness, addiction.

She rarely talked about her war years.

When she did, she didn’t mention troop movements or prisoner tallies.

She talked about the day forty-three women cried because someone had offered them soap.

“We beat Germany with tanks and planes,” she would say to the rare person who asked. “Sure. That’s how you win a war on paper. But we built the peace by how we treated the people in our power after. A bar of soap and hot water did more to kill Nazi lies in those women’s heads than any leaflet we ever dropped.”

In 1975, at a small church luncheon, someone asked her what the most powerful thing she’d ever seen in uniform was.

She took a breath.

“Forty-three women,” she said, “standing in the Oklahoma sun, shaking apart because they couldn’t believe we were going to let them be clean again. Because for them, kindness was more unbelievable than cruelty. And realizing I got to decide, in that moment, whether we would prove them right or wrong.”

She smiled sadly.

“Sometimes the fiercest weapon you have isn’t a gun or an order,” she added. “It’s a choice. To treat someone decent when you could get away with doing the opposite.”

History books didn’t mention Camp Gruber’s soap incident.

They didn’t mention the smell in the air that April morning, or the way a plain bar of Army soap felt in hands that hadn’t touched anything like it in a year, or the way hot water steaming on concrete could feel like an answered prayer.

But for the women who had stood there, and for the American women who had watched them, it became the moment the war’s big ideas—civilization versus barbarism, democracy versus dictatorship—stopped being slogans and turned into something tangible.

How you treat the people who can’t do anything for you.

How you act when no one is watching but God and your own conscience.

Sometimes, it turns out, you defeat an ideology not with leaflets or lectures or tribunals, but with a bar of soap and the simple, shocking message that even an enemy is still a person who deserves to feel human.

And sometimes, if you get that choice right, they cry—

And carry the memory home for the rest of their lives.

THE END

News

Amidst the chaos, they set up a makeshift aid station in a church displaying a prominent red cross, treating wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict.

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

German “Comfort Girl” POWs Were Astonished When American Soldiers Respected Their Privacy

The Day the Monsters Had Rules Schroenhausen, Bavaria April 1945 The engines came first. Margaret Miller pressed her forehead to…

My husband left us for his mistress—and three years later, I met them again. It was unbelievable, but satisfying.

After 14 years of marriage, two children, and a life I thought was happy, everything collapsed in an instant. How…

The Dishwasher Girl Took Leftovers from the Restaurant — They Laughed, Until the Hidden Camera Revealed the Truth

Olivia slid the last dish from a large pile into the sanitizer and breathed a sigh of relief. She wiped…

German Women POWs in Oklahoma Were Told to Shower With Water — And Burst Into Tears

Story title: The Day the War Fell Off Their Skin Camp Gruber, Oklahoma April 1945 The truck came in on…

“Are There Left Overs?” Female German POWs Were ASTONISHED When They First Tasted Biscuits and Gravy

Story title: Biscuits and Mercy Camp Somewhere in the American Midwest Late 1944 The first thing they noticed was the…

End of content

No more pages to load