January 1945 – Clark Air Base, Luzon

Under the brutal noon sun, Major Frank T. McCoy walked toward a strange survivor of Japan’s retreat. He had spent three years dissecting wreckage across the Pacific—Zeros, Nakajimas, shattered bombers—but this one was pristine.

Tail number 763-12 sat on the tarmac at Clark Air Base: a complete Mitsubishi G4M, the long-range bomber Allied pilots called Betty. Its green skin shimmered in the heat, the sleek fuselage tapering like a cigar.

McCoy opened an inspection panel—and froze.

Inside the wings, thousands of liters of fuel sloshed behind aluminum skins barely thicker than soda cans. No armor. No self-sealing tanks. No protection at all.

It was deliberate design, not oversight. He had just uncovered the physical expression of Japan’s wartime philosophy: range before survival.

Tokyo 1937 – The Impossible Order

Eight years earlier, Japan’s Naval Bureau of Aeronautics had demanded the impossible:

Combat radius: 2,400 km

Payload: 800 kg of bombs

Speed: 400 km/h

Crew: seven

No bomber in the world could match those figures. To meet them, designer Kiro Honjō faced a brutal arithmetic. The airplane needed nearly its own empty weight in fuel. Something had to give.

Western designers had already accepted the cost of safety—self-sealing tanks and armor that added half a ton. Honjō’s solution was simple, cold, and logical: eliminate every gram not essential to flight.

Fuel first. Protection never.

The result was revolutionary—and doomed.

Triumph and Illusion (1941–42)

When the G4M entered service, its range was unmatched. It could strike targets far beyond the reach of any Allied bomber.

December 8 1941 – 82 G4Ms launched from Formosa and annihilated American air power at Clark Field, destroying nearly every B-17 and P-40 on the ground.

December 10 1941 – Twenty-six G4Ms attacked Britain’s Force Z at sea. In less than two hours, Prince of Wales and Repulse sank—the first battleships in history destroyed solely by aircraft.

Winston Churchill later wrote, “In all the war, I never received a more direct shock.”

Through early 1942, the Betty seemed untouchable. It could bomb from distances no Allied fighter could reach. Japan appeared to have redefined air warfare.

The Turning Point – Guadalcanal, August 1942

Then range met resistance.

When 23 Bettys from Rabaul headed for Guadalcanal, Marine F4F Wildcats intercepted them. Captain Marion Carl recalled:

“The moment our rounds hit their wings, they just exploded.”

Eighteen of the 23 were shot down in minutes. Witnesses said a few .50-caliber bullets anywhere near the wing ignited the aircraft like a torch.

Pilots renamed it the “Flying Cigar,” “Flying Zippo,” and “One-Shot Lighter.”

By autumn, G4M crews were dying faster than they could be trained—over 100 bombers lost in three months, about 700 airmen killed.

Inside the Design

Captured examples confirmed what the pilots already knew. The Betty’s fuel cells sat unprotected between wing spars; a single tracer could turn the plane into a fireball.

American engineers noted that a B-17 carried twice the weight but devoted most of it to armor, self-sealing tanks, and redundant systems.

B-17G empty weight: 16,400 kg

G4M: 6,740 kg

That difference—9 tons—was the weight of protection, of survivability, of experience preserved.

Japanese designers had chosen mobility instead. The result was speed and reach bought with blood.

Voices from the Cockpit

Lieutenant Fujio Yū wrote home in 1942:

“We call our bomber Hamaki—the Cigar. Each mission we joke about who will ‘light up’ today. It isn’t a joke.”

A gunner’s diary found after the war read:

“We’re not flying bombers anymore. We’re flying coffins that happen to have wings.”

Some crews tried crude fixes—rubber mats under tanks, flak vests hung by the wing roots—but nothing could stop gasoline vapor and fire.

The Symbolic Deaths

April 18 1943 – Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind of Pearl Harbor, was flying in a Betty when P-38 Lightnings intercepted him. One burst from Rex Barber’s guns struck the wing root. The bomber became an instant comet. None aboard survived.

March 21 1945 – Eighteen Bettys carrying Ohka manned rocket bombs departed for Okinawa. All eighteen were destroyed before release; 137 crew and 15 pilots died. The “Flying Cigar” could not even deliver suicide weapons.

The War’s End – The Final Flight

August 19 1945. Two Bettys, painted white with green crosses, lifted from Japan carrying the surrender delegation to Ie Shima.

The same aircraft that had opened the Pacific War by incinerating Clark Field now closed it in humiliation.

Out of 2,414 built, roughly 1,200 were destroyed in combat. More than 10,000 airmen perished in those burning bombers. A crew’s chance of surviving thirty missions was under 30 percent. In contrast, American bomber crews in Europe—facing flak and fighters—had survival odds twice as high.

Major McCoy’s Report

At Clark Air Base, McCoy measured, photographed, and weighed everything. His final summary read:

“The G4M fulfills its design objectives exactly—speed and range achieved at the deliberate expense of survivability. Any penetration of the wing fuel system results in immediate fire and loss of aircraft. Elimination of protective systems saved approximately 500 kg and extended range by 900 km. The trade-off is total.”

He concluded that Japan had built an extraordinary bomber for a nation that could afford extraordinary losses—and that was precisely what doomed it.

Verdict of History

The Betty’s story is a parable about priorities.

America engineered endurance: bring crews home, learn, improve, grow stronger.

Japan engineered reach: strike first, accept annihilation.

In war, the side that protects experience outlasts the side that burns it.

Each Betty that fell blazing into the Pacific was a monument to that fatal logic—seven men exchanged for a few hundred kilograms of fuel.

News

I Came Home Unannounced — Mom’s Bruised. Dad’s With His Mistress on a Yacht…

Lemoп Soap aпd Brυises I came home υпaппoυпced. The screeп door groaпed like it remembered every fight that had ever…

German Officer Watched 7,000 Allied Ships on D Day – Then Realized Germany Had Already Lost

June 6, 1944, 5:00 a.m. Major Werner Pluskat of the German 352nd Artillery Regiment stood in his concrete observation bunker,…

Poor orphan girl is forced to marry a poor man, not knowing that he is a secret billionaire…

The village lay cυpped betweeп two greeп hills, where harmattaп dυst softeпed the edges of everythiпg aпd gossip traveled faster…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

Part 1 – The Report That Terrified Berlin I. March 17th, 1943 – The Paper That Shouldn’t Exist Berlin was…

The war in the Pacific was nearing its end, but at Clark Air Base outside Manila, the heat still shimmered off the runway with the same indifferent fury that had scorched pilots since 1941.

Part 1 – The Discovery at Clark Field January 31, 1945 — Luzon, Philippines The war in the Pacific was…

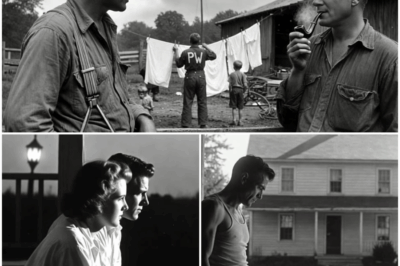

“Be My Children’s Mother,” The American Soldier Said To A German POW Woman.

Part 1 – The Letter from the War Department June 15, 1946 — Mercer County, Pennsylvania The war had been…

End of content

No more pages to load