The mornings always began the same, like a scene that refused to change no matter how many years passed.

Before the first sliver of daylight crept through the blinds of my son’s two‑story house on a quiet cul‑de‑sac outside Columbus, Ohio, I was already in the kitchen. The subdivision was the kind you see in Midwest real‑estate flyers—maple trees planted at perfect intervals, flags on porches, neighbors jogging with insulated coffee cups. Inside, though, my world had shrunk to a few square feet of linoleum.

I measured out coffee grounds by muscle memory, listening to the slow drip of the machine. I heated the pan and cracked eggs the way Saurin liked them—firm whites, no runny yolk, two slices of wheat toast, crusts on. He never said thank you, but I’d stopped expecting it years ago.

Instead, I listened for the familiar shuffle of his slippers overhead, the creak on the third stair, the little cough that meant he was on his way down. My timing was always perfect. Breakfast hot. Pills sorted by day and hour in the little plastic box. His newspaper folded beside his mug—the Columbus Dispatch he liked to flip through while the morning news hummed from the TV.

After my husband died, the small ranch we’d shared on the edge of town felt too quiet, too wide. The neighbors still waved from their driveways, the mail still came, the Ohio State flags still fluttered on game days, but every room in that house echoed with his absence.

I had nowhere else to go—at least that’s what I told myself. Not really. My daughter, Maribel, had her own family and a job teaching at a public school in another town. And though she never said it out loud, I didn’t want to be a burden.

So when my son, Saurin, said I could stay with him temporarily—he’d paused on that word, like it was a warning—I packed my things and moved in. That was nearly seven years ago.

At first, I tried to make it feel like home.

I brought my own curtains, soft blue ones with tiny white flowers, the ones my husband used to tease me about because they made the kitchen look like “a bed‑and‑breakfast in Vermont.” I stacked my recipe books on the counter, pages stained with oil and tomato sauce from decades of meals. I propped my old sewing machine against the wall in the spare room, imagining I’d finally finish the quilt I’d started the year Saurin left for college.

But little by little, those things disappeared.

The curtains “clashed with his minimalist aesthetic,” he said, rolling the word around like he’d just learned it from a podcast. He took them down and folded them into a plastic storage bin in the basement. The cookbooks collected dust until one day I realized they were gone—donated or boxed up without a word. The sewing machine ended up in the garage, behind boxes of tools he never used but refused to throw away.

“This is more my style,” he’d say, gesturing to the bare walls, the gray rug, the black leather couch that squeaked when you sat down.

I kept quiet. I adapted. I told myself that gratitude looked different for every generation, that this was what a good mother did—made herself smaller so her children could stretch out.

What I didn’t say aloud—not to him, not even to myself at the time—was that the walls of my world had been shrinking, room by room, until all that remained was the kitchen and the laundry room.

My universe became his preferences, his routines, his moods.

I knew the exact sound his car made when he turned onto the street. I knew which days he came home irritable from the insurance office and which days he came home smug because his numbers were better than his coworkers’. I knew when to keep the TV volume low, when to avoid asking questions, when to pretend I didn’t hear him sighing about how tired he was.

I cooked, cleaned, and ran errands with a kind of practiced invisibility.

The pharmacy clerk knew me by name. The cashier at Kroger would ask how “your son” was doing, and I’d smile and say, “Busy. Always busy,” as I paid with his debit card and tucked the receipt into my wallet to show him later. On days when the Ohio wind knifed through my coat in the parking lot, I would wrap my scarf tighter and remind myself that at least I wasn’t alone in that empty old house.

And still there were days he’d snap at me for using the wrong detergent or reheating leftovers he didn’t remember liking.

Once, on a gray Sunday afternoon when the sky hung low and heavy, I mentioned how I missed gardening, how I used to grow tomatoes and basil along the fence back at the old house. I could almost smell the warm dirt, hear my husband humming some old Motown song while he grilled in the backyard.

Saurin didn’t look up from his phone.

“Well,” he said, thumbs still moving, “you can do that when you get your own place again.”

He meant it like a joke, but the sting stayed long after he’d scrolled onto the next thing.

Every now and then, I’d glance at the closet where I kept a small suitcase, just in case. I told myself it was there for emergencies—for hospital visits, or sudden travel. But sometimes I’d sit on the edge of the bed and look at it longer than necessary, wondering what it would feel like to walk out with just that, no explanations, no apologies.

It was a thought I never voiced.

Not until the day everything changed.

It was just after lunch on a Tuesday. Outside, the late‑winter light slanted thinly across the snow‑salted sidewalks, and the hum of the furnace filled the quiet house. I was rinsing out Saurin’s coffee cup when the phone vibrated against the counter.

Maribel’s name flashed on the screen, and something in my chest tightened. She never called during the workday.

I wiped my hands on a dish towel and answered with a brisk, “Hi, sweetheart.”

But her voice didn’t carry the same warmth.

“Mom,” she said quickly, breath catching. “It’s Isa. She fell during gym class. She broke her arm.”

The cup slipped slightly in my grip, porcelain clinking against the sink. I grabbed the edge of the counter to steady myself.

“Is she all right?” I whispered. “Where is she now?”

“At the hospital,” Maribel said. “The county one off Route 23. She’s with me. They’ve already put on a cast. She’s out of school for at least a couple of weeks and…” Her voice thinned to a fragile thread. “Well, I can’t stay home with her.”

Behind her words, I could hear the faint beep of hospital machines, the echo of announcements over the intercom, the crinkle of paper sheets.

I didn’t hesitate.

“Do you want me to come?” I asked.

She exhaled, and I heard the strain in her silence, the way her composure frayed right at the edges.

“I wouldn’t ask if I had another option,” she said. “The school evaluations are next week. If I miss more than two days, it affects my contract renewal. You know how the district is.”

“I’ll come,” I said before she could finish. “I’ll be there tomorrow morning.”

There was a beat of quiet, then a small, cracked “Thank you, Mom.”

When I hung up, I stood still for a long moment, the weight of habit pressing against the decision I’d already made. The kitchen clock ticked over the sink. A snowplow rumbled distantly down the main road.

Then I dried my hands, went upstairs, and took the suitcase from the closet.

I set it on the bed and opened it slowly, like I was unsealing a part of myself I hadn’t dared look at in years.

Just a few clothes. Some toiletries. My copy of “The Wind in the Willows.” Isa loved that one. She always asked for “the part with Mr. Toad” in a whispery stage‑voice when she slept over in the old days.

I was folding a sweater when I heard Saurin’s key in the front door. The familiar click, the rush of cold air, the thud of his briefcase on the entry table.

His footsteps came up the stairs, heavier than usual. I didn’t realize he was at my door until his voice sliced through the air.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

I turned around, my hands still on the sweater.

“Isa broke her arm,” I said. “Maribel needs help. I’m going to stay with them a few days.”

His brow furrowed like I’d spoken in a foreign language.

“You’re leaving?” he said. “Just like that?”

“She needs someone,” I replied. “I can be there.”

He scoffed, a bitter sound that didn’t match the house he’d built to look so put‑together.

“And I guess I don’t need anyone?” he shot back. “Who’s going to take care of this place? Of me? What about dinner? My meds?”

It struck me then how easily he grouped himself with his house, as if they were one and the same thing to maintain.

“I’ve already organized your medications and written out meals for the week,” I said. “They’re labeled in the fridge. You’ll be fine.”

He took a step closer, jaw tight, eyes narrowed.

“If you walk out that door,” he said, each word low and deliberate, “don’t bother coming back.”

Once, those words would have shattered me.

I didn’t respond this time. Not with words, not with tears. I just looked at him, really looked at him—my son, taller than me, older than the boy I once tucked into bed after Little League games, standing between me and the doorway like a gate he thought he owned.

In his face, I saw a man who had grown used to me bending the world around his comfort. And in the quiet space between us, I felt a small, solid core of something that hadn’t existed there in years.

Then I turned back to the suitcase, folded the sweater, and zipped it closed.

My hands were steady.

“My bus leaves early,” I said quietly, even though I knew I’d be driving. “I’ll be leaving in the morning.”

He muttered something under his breath as he turned away, but I let it slide past me like static.

The house was still when I woke.

No footsteps overhead. No television murmuring from the living room. Just the soft hum of the refrigerator and the click of the heat kicking on.

I moved through the kitchen like I always did, measuring coffee, slicing fruit, scrambling eggs. I packed Saurin’s lunch with the same care I had every morning—a peanut butter sandwich, chips, a small apple he’d probably leave untouched. Habit is a hard thing to walk away from, even on the day you finally decide to leave.

I placed his pill organizer on the counter next to a glass of water and a folded note.

The handwriting was neat, the words brief:

All your medications are sorted through Friday. The leftovers are labeled. Don’t skip breakfast.

I didn’t sign my name. I didn’t need to. Every corner of that kitchen already bore my invisible signature.

Upstairs, my suitcase was already packed, but I walked the room again just to be sure. A sweater. A scarf. The lavender lotion Isa liked when she couldn’t sleep.

At the last minute, I opened the top drawer of the nightstand and pulled out a slim envelope—the one with my passport, my birth certificate, and the little savings booklet with my name—only my name—printed on the front.

Underneath that was another folder, one Saurin had never noticed or asked about. It held a copy of an old property deed and some letters my late husband had written—the kind that reminded me I had once been someone loved openly and chosen deliberately.

I slipped both folders into the bottom of the suitcase and zipped it shut.

I didn’t look around the room before I left it. I didn’t linger in the hallway or pause at the stairs. I walked through the house like a guest leaving after a long visit.

When I opened the front door, the cold Ohio morning air brushed against my skin like a reminder that there was still a world outside these walls.

Outside, the street was quiet. A school bus rumbled in the distance, its brakes squealing as it stopped at the corner. My car was parked under the bare maple tree just as I’d left it, windshield glittering with a thin shell of frost.

I loaded the suitcase into the trunk, settled into the driver’s seat, and turned the key. The engine hummed to life.

In the rearview mirror, the house stood perfectly still. No curtains moved. No shadow passed behind the front window.

I didn’t wait for a goodbye.

I didn’t expect one.

As I turned out of the neighborhood, my phone buzzed with a new message. It was from Maribel:

Call when you’re close. Isa hasn’t stopped asking when Grandma’s coming.

By the time I pulled into Maribel’s driveway, the late‑morning sun had melted away the frost that clung to the trees along the county road. Her house was small, single‑story, pale blue, with a crooked wind chime by the porch and a faded American flag fluttering from a bracket. The siding had seen better days, but there was a warmth to it, a kind of lived‑in softness I hadn’t felt in years.

Before I could open the car door, the front door burst open.

Isa came running down the small concrete steps, one arm in a pink cast, the other outstretched like a little bird launching itself.

“Grandma!” she shouted.

I barely had time to bend down before she threw herself into me, face buried in my coat. Her body trembled slightly—not from pain, but from holding too much emotion in too small a frame.

I held her tight, breathing in the scent of artificial strawberry shampoo and school hallway dust, brushing her hair back, whispering, “I’m here, sweetheart. I’m here.”

Inside, Maribel gave me a quiet hug and helped with my suitcase. She looked tired, her eyes rimmed with the kind of exhaustion that comes from grading papers at the kitchen table under harsh fluorescent light and waking up early for a school run in February, but there was relief behind her eyes.

“Thank you for coming,” she said softly.

“That’s what grandmas are for,” I replied.

That evening, I made lentil soup with the few ingredients she had in her pantry—a bag of dried lentils, a couple of carrots, an onion, some garlic, a dusty jar of cumin. We sat around the small kitchen table, elbows nearly touching. The laminate was chipped at the corners, a small burn mark near my elbow.

Isa told me about the fall, how she slipped on the monkey bars during recess, how the nurse gave her a popsicle at the school nurse’s office before the ambulance came. Her eyes grew wide when she described the X‑ray machine, how “it looked like something from a superhero movie.”

She grinned when I said we’d draw smiley faces and tiny flowers on her cast tomorrow, maybe even a little Mr. Toad if I could manage it.

After dinner, I helped her into her pajamas, propped her casted arm on a pillow, and sat beside her bed with the old paperback I had packed just for this. Her eyes fluttered as I read, her small body inching closer with each page until her head rested against my hip.

When her breathing slowed, I kissed her forehead and turned off the lamp, leaving the hall light on the way she liked, spilling a narrow strip of gold across the carpet.

Back in the kitchen, Maribel poured me a cup of tea from the chipped kettle on the stove. The window over the sink showed a slice of the dark yard, a neighbor’s porch light glowing like a distant star.

“She’s already calmer,” Maribel said, staring into her mug. “She’s been waking up crying the past two nights. Tonight was different.”

I nodded, wrapping my hands around the warm ceramic.

“She just needed a little comfort,” I said. “That’s all.”

Maribel looked at me, her voice quiet but steady.

“Stay as long as you want, Mom,” she said. “We’ll make room. We’ll figure it out.”

I didn’t respond right away. I just looked around at the cramped counters, the chipped tile, the children’s drawings taped to the refrigerator door—a rainbow, a stick‑figure family, a crooked heart colored in red crayon. There were spelling tests held up with magnets shaped like fruit, a grocery list scribbled on the back of a PTA flyer.

For the first time in years, I didn’t feel like I was in someone else’s home.

Later that night, after they’d both gone to bed, I took the folders from my suitcase and laid them carefully on the small desk in the corner of the guest room.

The next morning, I woke before anyone else. The house was quiet, save for the occasional creak of the old floorboards and the soft hum of the refrigerator.

I sat at the little desk, the two folders spread open in front of me like a life I’d half‑forgotten I had.

The first held the bank statements I’d quietly maintained over the years at a credit union downtown. Small deposits. Birthday money. Leftover change from grocery runs. An old tax refund I never mentioned. A fifty‑dollar bill here, a twenty there, tucked away each time Saurin sent me to the store and told me to “keep the change” like he was doing me a favor.

It wasn’t a fortune, but it was mine.

The balance wasn’t impressive, but it was solid—a number that said, You exist outside of someone else.

The second folder took longer to open.

I remembered the day I found it tucked in the back of an old file box in the basement after my husband passed, when I’d gone looking for insurance papers and come up with dust on my hands and old memories under my nails.

A copy of the property deed, yellowed slightly with time. I’d never really read it through until recently, but there it was, clearly printed—his name. Only his. Never updated.

Saurin had always assumed the house was his. He’d spoken of it like it was, had lorded it over me more times than I could count.

“You’re lucky I let you stay here,” he liked to say when he was in a mood. “My mortgage. My house. My rules.”

But legally, things weren’t that simple.

I traced my fingers along the bottom of the page where the notary seal had once been pressed. Part of me had been afraid to know what this all meant, but fear had kept me still for too long.

So I picked up my phone and dialed Rowan.

He answered on the second ring.

“Deline, everything all right?” he asked.

Rowan had been my husband’s friend back when they both worked at the factory on the edge of town, when Friday nights meant beers on the back porch and Buckeyes games on the radio. These days he practiced law out of a small office above a barber shop near the county courthouse.

“I need to ask you something,” I said.

My voice shook on the first word, but steadied as I went on.

I told him about the property rights, about what someone assumes they own. I explained what I’d found—the documents in front of me, the account I’d quietly managed all these years.

I heard him scribbling something in the background, the faint scratch of pen on legal pad.

“Deline,” he said finally, “you’re not crazy. If your husband never transferred title or included Saurin legally, the house may still fall under probate terms, or at minimum, partial rights belong to you, depending on state law.”

“There was no will,” I said softly. “He died suddenly. We never got around to it.”

“That might actually work in your favor,” Rowan replied. “Intestate succession isn’t always simple, but it doesn’t automatically hand everything to the children. Not if there’s a surviving spouse who contributed.”

I leaned back in the chair, the weight of years pressing down all at once.

“Saurin’s been using that house like he inherited it,” I said. “Like he owns it outright.”

“Well,” Rowan said, “then he’s been living in a story he wrote himself. Legally, he may own far less than he thinks.”

I didn’t speak.

I just stared at the deed, feeling something inside shift—not with rage, but with clarity. It was like seeing a familiar street in a new light and realizing the turn you thought you had to take was never your only option.

All those years of being told I had nothing. And yet, here were the quiet proofs, patiently waiting in a manila folder.

After I hung up, I folded both folders closed, slid them back into my suitcase, and zipped it with steady hands.

From the other room, I heard Isa calling my name, her voice bright and unbothered by adult things like deeds and titles.

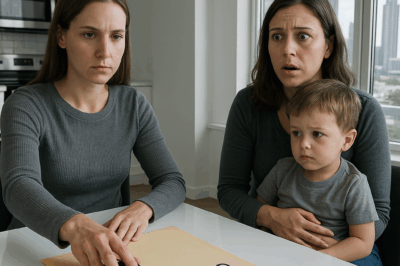

It happened three days later, just after sunset.

Maribel was still at work, stuck at a parent‑teacher conference at the middle school. Isa and I had just finished folding laundry in the living room while some sitcom rerun played softly in the background, the laugh track rising and falling like a tide we weren’t part of.

A heavy knock rattled the front door.

Not a knock of politeness. It was sharp, impatient—the kind that doesn’t ask permission to enter.

My hands froze mid‑fold, a tiny T‑shirt hanging limp between my fingers.

Isa looked up at me with wide eyes.

“Stay here,” I said softly.

I walked to the door, heart steady in a way that surprised me, and opened it just enough to see the figure outside.

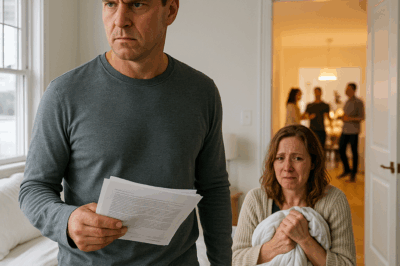

Saurin stood there, jaw tight, eyes storming. He looked like he hadn’t slept much. His shirt was wrinkled, his tie half‑loosened, his shoulders stiff with indignation.

Behind him, the streetlights cast long shadows across the patchy grass.

“You’ve ignored all my messages,” he said, his voice low but seething.

“I know,” I replied calmly.

He stepped closer. I could smell the stale coffee and faint aftershave on his breath.

“What are you doing here?” he demanded. “Playing house? Taking what doesn’t belong to you?”

I didn’t flinch.

“I’m helping my granddaughter,” I said. “That’s what I came to do.”

“You left me,” he snapped. His tone cracked on the last word—more accusation than injury. “You took money. You took documents. That’s theft, Mother.”

I exhaled slowly through my nose.

“No, Saurin,” I said. “I took what was already mine.”

His gaze flicked past me, taking in the small, tidy living room, the pile of folded laundry on the coffee table, the cartoon still playing on mute.

“You’re staying here now?” he said, scanning the small porch, the modest siding, the weed‑choked strip of lawn. “You gave up your place in a real home for this?”

You told me not to come back, I thought, but I said it out loud instead.

“You told me not to come back,” I reminded him. “I didn’t argue. I left. You made the decision easier than I expected.”

Behind me, Isa peeked through the doorway, her small hand curling into mine. I didn’t hide her. I let her stand there beside me, feeling her presence anchor my words, a quiet reminder of the generations watching us.

“I needed you,” Saurin said. “Everything’s been chaos since you walked out.”

“You didn’t need me,” I said evenly. “You needed a cook, a cleaner, a caretaker. Not a mother. Not a person with her own life.”

His face twisted, but he didn’t speak. For the first time in our lives, he seemed to be searching for a script that no longer worked, flipping through invisible pages and finding every line out of date.

A porch light flicked on two houses down. Somewhere, a dog barked.

“I’m not angry,” I said, and to my own surprise, I meant it. “But I’m not returning to a life where I don’t exist except in service. That part of my story is done.”

Isa’s grip tightened. I squeezed her hand back.

“You’ve really changed,” Saurin said finally, the words sounding more like a warning than a statement.

“No,” I said. “I finally stopped pretending.”

He stared at me for a long moment, then turned and walked down the steps without another word. His car door slammed, the engine roared to life, and he drove off into the darkening street.

I closed the door gently behind him and locked it with a quiet click.

From the kitchen, the kettle began to whistle. I walked back inside and poured two mugs of tea, one for me and one for Maribel, who would be home soon from the school off the highway where she taught.

The steam rose steadily into the soft light of the room. Isa leaned her head on my arm as I sat beside her on the couch, the muted glow of the cartoon painting her face in shifting colors.

Rowan filed the initial paperwork that Thursday.

The envelope felt heavier than its size should have allowed when I slid it across the counter at the small post office on Main Street. The clerk weighed it without comment, slapped a barcode sticker on it, and pushed it toward the outgoing bin.

Inside were the petitions for asset division and a formal claim to my share of the house. My name was on every page, clear and spelled correctly, not just a shaky signature at the bottom of someone else’s document.

When we returned to the house, Rowan sat with me at the kitchen table while Isa’s little sister, Elyn, napped in the next room and Maribel caught up on grading papers.

His voice was calm, professional, but not cold.

“We’ll start with property discovery,” he said, tapping the folder. “There’s a strong case for your financial contribution through domestic labor, especially if there was no formal will after your husband passed. Ohio courts have seen this before.”

I nodded, my fingers wrapped around a chipped mug of coffee.

“Saurin’s going to be furious,” I said.

“He already is,” Rowan replied. “But that’s not your burden to carry.”

Later that night, my phone buzzed. A message from Saurin:

You really want to air this out in public? Fine. Just remember who paid for everything while you lived under my roof.

I didn’t respond. I deleted the message and silenced the phone.

A few days later, another arrived. This time, a voicemail. His voice was softer, almost pleading.

“Mom, we’re family,” he said. “We’ve both said things. You’re being dramatic. Just come home. We can figure this out.”

But there was no home to return to—only a house built on expectations, not understanding.

I’d lived under his roof, yes, but I had kept it clean, kept him fed, kept the very walls from feeling less empty. That was never nothing.

Rowan stopped by again the following week with updated forms. We sat at the same small table, steam rising from two mismatched mugs of coffee.

He reviewed the documents one last time before sliding them toward me.

“You don’t owe him your peace just because he gave you shelter,” he said, his voice steady. “What you’re doing now—it’s not revenge. It’s restoration. You’ve been paying for that roof for years, just in a currency nobody bothered to count.”

The word settled into me like a stone in a riverbed—heavy, real, changing the current. For the first time, I saw the balance sheet of my life not as a blank page, but as a ledger quietly filled in my handwriting.

I thought of every grocery list, every 5 a.m. breakfast, every load of laundry, every pill sorted into plastic squares. All the invisible labor that had kept Saurin’s world running like a well‑oiled machine while mine sat parked in the dark.

I picked up the pen and signed.

That night, after the house had settled and everyone was asleep, I opened a blank notebook and began drafting my new will.

It was simple but deliberate. I listed my savings, my potential share of the house if the court awarded it, and the items I wanted to pass down. Maribel’s name appeared first, then Isa’s and little Elyn’s.

As I turned the page, I tucked something between the sheets—a drawing Isa had made just the day before. Three figures hand in hand beneath a sun with uneven rays. One wore glasses. One had curly hair. One had a cast on her arm.

Scrawled above in crooked, bright letters were the words: My real family.

I pressed the notebook closed and slid it into the top drawer of the desk. My fingers lingered on the spine for a moment.

The old will had never existed. This one did.

The next morning, I opened the curtains in the guest room and let the sunlight pour across the desk. Outside, kids waited at the corner for the school bus, their backpacks slung low. A dog barked somewhere down the block. A mail truck rattled past, its brakes squeaking.

Life went on.

The final signatures came on a rainy afternoon a few months later.

Rowan slid the last page across the table in his cramped office above the barber shop, his hand steady, his presence reassuring. The rain drummed against the window, turning Main Street into a watercolor of blurred headlights and wet pavement.

I didn’t hesitate. I signed, and it was done—twenty years of widowhood and seven years of quiet servitude wrapped into a few strokes of ink.

No one cried. No one begged. There were no dramatic speeches, no slammed doors. Just a quiet finality and a strange, welcome weightlessness in my chest.

A week later, I moved into a small rental not far from Maribel’s place—a brick duplex with two rooms, a modest galley kitchen, and windows that faced a little city park where kids played pickup basketball in the evenings and teenagers lounged on the swings with their headphones in.

On Sundays, Isa would run up the path with her backpack bouncing and her cast now replaced by healing skin. We baked together. We read stories out loud. We laughed. Sometimes we just sat in silence, listening to the hum of the refrigerator and the distant thump of a basketball hitting asphalt, and even that felt full.

I bought a couple of potted tomato plants and set them on the small balcony. It wasn’t the garden I’d once had, but it was mine. I ran my fingers through the soil and thought, This is what it feels like to plant something for yourself.

I hung my curtains—the same soft blue ones with tiny white flowers—in the kitchen. They fit the window perfectly.

One evening, just as I was pulling cornbread from the oven—my husband’s old recipe, the one he used to request with chili on cold nights—there was a knock at the door.

I wiped my hands on a dish towel and opened it.

Saurin stood there, thinner than I remembered, his hair grayer, his shoulders curled in slightly like the winter had settled into his bones. He looked older in a way that had nothing to do with age.

He didn’t say hello. He just looked at me for a long time before asking, “Are you happy now?”

It wasn’t an apology. It wasn’t even a question, not really. It was an accusation wrapped in disbelief.

I met his eyes. There was no anger in me anymore, just space.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “Finally. And the best part is, it doesn’t depend on you anymore.”

The word hung between us, simple and undeniable.

He nodded once, slowly, as if the answer landed somewhere he hadn’t expected. For a heartbeat, I thought he might say something else. But he just turned and walked back toward his car parked along the curb.

The taillights glowed red for a moment, then disappeared down the street.

I closed the door gently behind him, not with bitterness, not with triumph, but with peace.

Some endings don’t need fireworks.

They just need silence.

Later that night, I opened the drawer beside my desk and took out a manila folder. Inside were my new legal papers, my updated will, Isa’s drawing, and a few letters I’d begun writing to myself—small reminders of who I had become.

I picked up a small label from the desk, the kind I once used to mark Saurin’s school supplies when he was young, and pressed it across the front of the folder.

In neat, careful handwriting, I wrote:

The year my voice returned.

Months passed, and the new life I’d stepped into stopped feeling new and started feeling normal.

I learned the sounds of my own neighborhood—the slam of the screen door from the unit next‑door when Mrs. Harper took her beagle out, the squeak of the park swings, the distant whistle of the freight train that cut across town after midnight. I learned how my little kitchen looked in every kind of light: sunrise glancing off the clean sink, afternoon sun warming the potted tomatoes, streetlamps washing everything in a soft orange glow.

I cooked what I wanted, when I wanted. Some nights that meant a proper dinner; other nights it meant popcorn and sliced apples in front of an old black‑and‑white movie with Isa and Elyn curled up under the same blanket.

There were small, quiet luxuries I hadn’t realized I’d missed: leaving a book open on the table without anyone moving it, humming while I washed dishes, letting the radio play old Motown songs without someone complaining it was “too noisy.”

Once a month, I met Rowan at his office to go over updates.

The first time he slid a copy of the court’s preliminary order toward me, my hands trembled—not from fear, but from the shock of seeing my name not as an afterthought, but as a rightful owner.

“The judge agrees there’s a strong claim to your share of the equity,” Rowan said, tapping the highlighted section. “Your years in that house count. You didn’t just live there. You maintained it. You preserved its value.”

I read the paragraph three times. Each sentence felt like someone quietly returning items that had been borrowed so long they were assumed gone.

Saurin fought, of course.

Through his lawyer, he sent counterclaims and affidavits, statements dressed up in legal language that boiled down to the same old story: it was his roof, his mortgage, his sacrifice.

But this time, there was something he hadn’t counted on—paper with my name on it and a spine in my back that no longer bent.

At the mediation, he couldn’t look at me for the first twenty minutes. He stared at the table, at the wall, at his own hands. I watched him the way you watch a storm roll past a field you no longer live beside: with concern, but from a safe distance.

When he finally did glance up, his eyes flicked to mine, then away again, as if he’d brushed against a truth he wasn’t ready to hold.

The mediator went through the numbers, the dates, the documents. Every time my years of cooking, cleaning, and care showed up in the calculations, I felt something inside of me stand a little taller.

In the end, the agreement was simple on paper and monumental in my heart.

I would receive a legally recognized share of the house proceeds if it sold, plus reimbursement for certain expenses I’d covered from my own savings. He would keep his pride—if that’s what he still wanted—and a smaller story of “doing it all himself” that no longer matched the records.

When the final agreement was read aloud, there was a long stretch of silence. The air felt thick, like the pause before a thunderclap.

Saurin’s lawyer cleared his throat.

“Do you agree?” the mediator asked him.

He swallowed.

“I don’t have a choice, do I?” he muttered.

“You always have a choice,” I said softly. “You just don’t get to choose for me anymore.”

He flinched like the words had landed somewhere he didn’t expect.

He signed. I signed. The mediator signed.

The sound of the pen scratching over paper wasn’t loud, but it echoed in my chest like a door closing gently and locking from the inside—by my hand, for my protection.

Later, when the house finally went on the market, I didn’t drive by. I didn’t need to see the For Sale sign staked in the yard where I used to plant marigolds. I had already done my leaving.

When the sale went through, a check arrived in the mail with my name printed cleanly across it.

I held it for a long time at my small kitchen table, the afternoon light spilling over the laminate.

This is not a gift, I reminded myself. This is not charity.

This is a receipt for years no one saw.

I put a portion into savings, set aside some for repairs and emergencies, and quietly opened a small college fund for Isa and Elyn. The bank clerk smiled and asked if I wanted to name the accounts.

I thought about all the names I’d carried over the years—wife, mother, widow, burden, help.

“Call them ‘Isa’s Start’ and ‘Elyn’s Start,’” I said.

Because that’s what I wished someone had given me—a starting place that didn’t belong to anyone else.

Holidays looked different after that.

That first Thanksgiving in the duplex, the oven ran hot and the kitchen was too small, but we squeezed in anyway. Maribel brought a store‑bought pie she apologized for, even though it tasted like cinnamon and comfort. Rowan stopped by with a casserole “from his sister” that I strongly suspected he’d made himself.

We ate at my wobbly dining table, knees bumping, plates crowded too close together. Isa insisted we go around and say what we were thankful for.

“I’m thankful Grandma has her own place now,” she said, matter‑of‑fact, as if announcing the weather.

Maribel shot me an apologetic glance, but I just smiled.

“So am I,” I said.

After dinner, while the girls drew turkeys traced around their hands and Rowan argued good‑naturedly with Maribel about football teams, I stepped out onto the small balcony.

The air was cold, but the tomatoes—stubborn, late bloomers—still clung to the vines.

I thought about the question Saurin had asked me at my door: Are you happy now?

Under the dark November sky, with the sound of my granddaughter’s laughter spilling through the open window and the hum of some distant game drifting from someone else’s TV, I finally knew how to answer it in full.

Yes. I am happy. Not because everything is perfect, not because I won and he lost, but because my life fits back into my own hands.

I went back inside and closed the balcony door behind me. The warmth of the little apartment wrapped around me like an old, familiar coat.

Later that night, after everyone had gone home and the dishes were drying in the rack, I sat at my desk and opened the manila folder again.

The legal papers. The will. Isa’s drawing. My letters to myself.

On a fresh page, I wrote:

This year, I learned that leaving doesn’t always mean walking out with nothing. Sometimes it means walking out with everything that was yours all along—your name on the deed of your own life, your hands on the steering wheel, your voice in your own story.

I signed my name under the sentence—not as a witness, not as someone’s wife or someone’s mother.

Just as myself.

Then I closed the folder and slid it back into the drawer, listening to the soft, satisfying click as it shut.

The year my voice returned was also the year I finally listened to it.

News

A week before Christmas, I was stunned when I heard my daughter say over the phone: ‘Just send all 8 kids over for Mom to watch, we’ll go on vacation and enjoy ourselves.’ On the morning of the 23rd, I packed my things into the car and drove straight to the sea.

A week before Christmas, I was in the kitchen making coffee when I heard voices coming from the living room….

I won 50 million dollars in lottery money and carried my son to my husband’s company to share the good news. When I arrived, I heard cheerful sounds coming from inside. I made a decision.

My name is Kemet Jones, and I’m thirty-two years old. If anyone had asked me what my life was like…

My husband cut off contact for three years, his family told my child and me to move out: ‘You should find another place to live!’ On a rainy night, I held my 5-year-old son, standing and waiting for the bus. His older sister drove a luxury car up, stopped right in front of me and said: ‘Get in, I have something very important I want to tell you.’

The thunder outside had rumbled for hours, tearing the quiet Georgia night to pieces. Every boom felt like it was…

I drove to our lake house for Thanksgiving and found my wife sitting alone in the bedroom, crying. On the balcony, my daughter and her husband, together with another man, were happily clinking champagne glasses as they discussed selling our house.

I never thought retirement would lead me here—standing in my own lake house at midnight, watching my daughter toast champagne…

My whole family went to the beach together, and to me they said, “It’s better if you stay home and take care of the work.” I didn’t say anything. When they came back, my room was empty.

They told me to stay behind and work while they took Emily and Jake to the beach. Dad was already…

For five years, I silently worked extra jobs, saving every penny to pay for my husband’s medical tuition, hoping that the day he wore the white coat would be a source of pride for both of us. But right when he graduated, instead of thanking me, he placed an envelope in front of me and said, “You are no longer worthy of me.”

After the divorce, Amara vanished from his life without a forwarding address. One year later, Dr. Keon Sterling—now a rising…

End of content

No more pages to load