November 10th, 1943. Afternoon, at Rechlin—Germany’s primary Luftwaffe aircraft testing facility. Hauptmann Hans-Werner Lerche, chief test pilot, walked across the tarmac toward a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt that had been captured two weeks earlier.

The aircraft looked, to German eyes, like an insult to engineering. It was grotesquely fat, ungainly—“a flying milk bottle,” as German pilots joked. Lerche had read the intelligence briefings. American aircraft, he had been told, were crude, mass-produced machines built by a nation better at making refrigerators than fighters. The P-47 was supposedly the prime example. Heavy, unsophisticated, relying on brute force instead of elegant aerodynamics. German fighters—Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s—were precision instruments. The P-47 was a sledgehammer.

Within ninety minutes, Lerche would realize just how wrong that assessment was. The Americans had not built a crude fighter. They had built something far more dangerous: a practical one. An aircraft designed not for elite aces, but for large squadrons. Not for breaking performance records, but for breaking the enemy through sheer numbers and relentless availability.

He would write a report that very afternoon. It would be read, then ignored. History would vindicate him. Germany was building fighters for individual excellence. America was building fighters for industrial war. In total war, that difference would prove decisive.

Hans-Werner Lerche had been flying since boyhood. Born in 1916 in Breslau, he started with gliders in the early 1930s, fighting his way upward despite modest family means. When Hitler’s rearmament began, doors opened. By 1939, Lerche was a test pilot at Rechlin—the Luftwaffe’s equivalent to Wright Field in the United States or Farnborough in Britain.

Unlike fighter aces who flew one or two aircraft types in combat, Lerche flew everything: new German prototypes, production models, captured Allied aircraft. His logbook would eventually list more than 120 different types. A trained aeronautical engineer, he wrote frank technical evaluations. If an aircraft was flawed, he said so. If an enemy design had strengths, he documented them. Some Nazi officials disliked his brutal honesty, but his expertise was too valuable to discard. If Hans-Werner Lerche said an aircraft was good—or bad—people paid attention, even if they didn’t like what he said.

The P-47 he was about to test—nicknamed Beetle—had an unusual story. Its pilot, Lieutenant William Roach of the 358th Fighter Squadron, 355th Fighter Group, had become lost in poor weather during an escort mission on November 7th, 1943. His flight ran desperately low on fuel. One pilot crash-landed on a beach. Another bailed out over the North Sea. Only one pilot made it back to England.

Roach saw what he thought was an English airfield. He landed safely, rolled to a stop, and followed a ground vehicle to parking—only to realize, too late, that he was not in England at all. He had landed at a Luftwaffe base in Caen, France. German troops surrounded the P-47. Roach became a prisoner of war. His aircraft became a prize.

The Luftwaffe quickly flew the captured Thunderbolt inland to Rechlin to keep it safe from Allied strafing. Now, with German camouflage and the code T9+FK, it awaited evaluation by Zirkus Rosarius, the Luftwaffe’s special unit for demonstrating Allied aircraft.

Lerche had heard the jokes and scoffing remarks. The P-47 was “too big,” “too heavy,” “typical American excess.” Yet he’d flown enough British and American types to know those engineers were no fools. If they had built an aircraft that looked this odd, there had to be reasons.

As he neared Beetle, the first thing that struck him was its size. The radial engine was enormous, the fuselage wrapped around it like a barrel. The landing gear was thick and solid. Where German fighters were slender and elegant, this thing looked almost like a small ship with wings. But the closer he looked, the less “crude” it seemed. Welds were clean. Panel seams were neat. Materials were clearly high grade. This was not rough work. It was high-quality mass production.

Lerche climbed into the cockpit. German pilots often complained that Allied cockpits were “roomy to the point of absurdity.” Compared to the BF 109’s cramped, almost coffin-like cockpit, the P-47’s was huge. A German pilot used to a tight fit might feel lost. But once Lerche settled into the seat, he understood.

In the Bf 109, he had to duck to avoid banging his head on the canopy. Controls and instruments were cramped. Long flights were physically punishing. German design philosophy placed performance above comfort; if the pilot suffered, so be it.

The P-47 cockpit was genuinely comfortable. The seat was padded. There was space to shift and stretch—important on missions that could last seven or eight hours. The canopy was high and gave excellent visibility. Controls fell easily to hand without stretching. None of that improved peak performance in a dogfight—but all of it improved long-term endurance. Lerche saw the logic immediately.

Then he examined the instruments and controls. One thing jumped out: the gauges were color-coded. Red and green zones indicated safe and dangerous ranges. A pilot didn’t have to read small numbers; a glance was enough. Lerche understood why. Intelligence reports had indicated that American squadrons included pilots from many nations—French, Polish, others—some with limited English. Color-coded instruments meant a pilot who barely spoke the language could still operate the engine safely. Green was good. Red was bad. Simple. Effective.

That wasn’t crude engineering. That was smart human-factors design.

The control layout was similarly intuitive. Throttle, mixture, and prop controls were grouped on the left. Fuel system controls were clearly labeled. Systems that Germans often scattered or made complex were streamlined here.

By 1943, Lerche knew how much this mattered. German fighters like the Bf 109 were increasingly difficult for raw recruits. Narrow landing gear made takeoff and landing hazardous. Engine and propeller controls required fine handling. The Luftwaffe’s once-comprehensive pilot training program had been gutted by fuel shortages. New pilots got far fewer flight hours before combat. Yet the aircraft they were asked to fly had not become any easier.

American designers, by contrast, clearly assumed varying skill levels. The P-47’s cockpit and systems made life easier for average pilots.

Lerche began his preflight. The manual was straightforward, step-by-step. German manuals often assumed technical familiarity. American manuals assumed nothing and explained everything. He started the engine.

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial came to life with a deep, powerful rumble. Then it settled into an impressively smooth idle. Lerche had flown enough American aircraft to notice a pattern: their engines were consistently smooth and reliable. German engines, especially later in the war, were becoming temperamental. Manufacturing variations between factories meant not all engines behaved identically. Replacement parts didn’t always fit. Engines that performed perfectly in tests developed serious issues in the field.

The R-2800 felt like it could run all day. No odd vibrations. No rough transitions. Just steady, reliable power. Building one perfect engine was one thing. Building thousands that behaved exactly the same under combat conditions was something else entirely. That, Lerche realized, was the real power of American industry.

Taxiing out, he felt another difference. The P-47’s landing gear was wide and stable. The tailwheel could be locked straight. The aircraft tracked well on the ground. In a Bf 109, taxing and landing were often more dangerous than combat. The narrow gear and poor forward visibility caused countless accidents. Many German fighters were damaged or destroyed without an enemy in sight. The P-47 was clearly built to reduce such peacetime losses and make rough-field operations safer.

Lining up on the runway, Lerche advanced the throttle. Acceleration was strong. The takeoff run was longer than a Bf 109’s, but not dramatically. The big fighter lifted off smoothly. Gear up, climb established, Lerche began testing its handling.

The P-47 did not feel “nimble” in the way German fighters did. It didn’t snap-turn like a Bf 109 or Fw 190. It wasn’t razor-quick in roll and pitch. But it was solid and predictable. It went where he pointed it, without surprises. The controls felt well-balanced. He tried flaps, power changes, and steep turns at safe altitudes. All systems behaved as expected.

Climbing above 15,000 feet, the P-47’s real strength appeared. Its turbo-supercharged engine maintained power and performance where German fighters began to lose breath. In dive tests, its acceleration and stability impressed him. The roll rate at high speed was excellent for such a large machine.

Nothing about the P-47 shouted “best dogfighter in the world.” Instead, Lerche found something more subtle and, in many ways, more impressive: it simply worked. In all regimes. Consistently. With no nasty quirks.

He flew for about ninety minutes, putting Beetle through a wide range of maneuvers. The engine never sputtered. The controls remained smooth. Systems did what they were supposed to do. It was, in his test pilot vocabulary, operationally sound.

That was when the deeper truth crystallized for him: the P-47 wasn’t designed to be the ultimate fighter. It was designed to be the ultimate operational fighter.

German engineers designed for peak performance—on the assumption of expert pilots, perfect maintenance, and adequate fuel. American engineers designed for sustained operations—on the assumption of mixed pilot skill, field maintenance, and rough conditions.

A perfectly maintained Bf 109 in the hands of a top pilot might beat a P-47 in a classic dogfight. But how often, in 1943–44, did the Luftwaffe enjoy “perfect maintenance” and “top pilot” conditions? The Americans, by contrast, were fielding an aircraft designed to be forgiving of imperfection—and doing so in overwhelming numbers.

Lerche landed and taxied back in. The robust gear soaked up his touchdown without complaint. Ground crews and officers clustered around, waiting for his verdict on the ugly American fighter.

“It is the best-designed operational fighter I have ever flown,” he said.

The mechanics were puzzled. Best-designed? It was heavy, bulky, and hardly a beauty. “It’s not designed for pure performance,” Lerche explained. “It’s designed for operations. And that is something different.”

That night he wrote his report.

He divided it into four main sections: performance, handling, systems, and strategic assessment.

Under performance, he listed the raw facts. Fast at altitude, sluggish at low level. Climb rate adequate but not exceptional. Dive performance excellent. High-altitude performance outstanding.

Under handling, he noted stable, predictable behavior; easy ground handling; generally forgiving flight characteristics; excellent visibility; a comfortable cockpit well-suited to long missions.

Under systems, he documented color-coded instruments, ergonomic control grouping, robust construction, and the smooth, reliable R-2800 engine.

Then came the strategic assessment:

“The P-47 Thunderbolt represents a fundamentally different design philosophy than that of German fighters. German aircraft are optimized for peak performance and assume expert pilots and maintenance. The P-47 is optimized for operational reliability and assumes average pilots and field maintenance.

This aircraft is designed to be operated in large numbers by pilots of varying skill levels. Its forgiving handling reduces accidents. Its robust construction increases the number of aircraft that return from missions. Its reliable engine reduces downtime. Its intuitive controls shorten training time.

Most importantly, every design decision prioritizes sustained operations over peak performance. The Americans have not built the best fighter. They have built the most operational fighter—and they can produce it in numbers we cannot match.”

He concluded with a recommendation: German fighter design must begin prioritizing operational reliability as a primary requirement. “We cannot win an attrition war against an enemy that can keep more aircraft flying, more consistently,” he wrote.

The report went up the chain of command. It was read—and then largely dismissed. Official attitudes did not change. German engineering was “superior”; American aircraft remained officially categorized as crude and clumsy. End of discussion.

But within months, Lerche’s predictions became reality.

By early 1944, P-47 Thunderbolts appeared over Germany in massive numbers. They escorted U.S. bombers deep into the Reich. They came day after day. German fighters could shoot some down, but replacements kept arriving. Luftwaffe pilots complained that even badly damaged P-47s often limped home, only to return to combat a few days later.

Meanwhile, German fighter production was buckling. Allied bombing disrupted factories. Shortages of high-quality alloys, ball bearings, fuel, and skilled labor took their toll. Engines failed more often. Systems became less reliable. The number of aircraft “on paper” no longer matched the number actually ready to fly.

American aircraft, by contrast, were designed for ruggedness and ease of maintenance. In many units, 85–90% of P-47s were available for operations at any given time. A German unit with 100 fighters might only have 60–70 ready, with the rest grounded for parts, fuel, or repairs. Multiply those numbers across the entire front, and the operational balance tipped hard in America’s favor.

Lerche continued testing captured planes throughout the war, including the P-51 Mustang, which impressed him with its mix of speed and range. He flew Spitfires, Hurricanes, and Soviet designs. All reinforced his earlier conclusion: Allied aircraft, and especially American ones, were built around operational reliability.

After the war, Allied technical officers interrogated Lerche, examined his reports, and were struck by how early and clearly he had seen the pattern.

“You concluded that American aircraft were superior, not necessarily in raw performance, but in operational design,” one American officer said. “That’s an unusual assessment.”

“It was the most important one,” Lerche replied. “Your pilots were not always better than ours. Your aircraft were not always faster or more agile. But you could keep more aircraft flying, more consistently. You could train more pilots. You could sustain operations we could not.”

Asked if German leadership had understood this, he reportedly laughed. “My report was filed. The official position remained that American aircraft were crude. Our engineering was superior. And any evidence to the contrary was considered defeatist.”

Could it have made a difference if Germany had adopted a similar philosophy? Lerche was cautious. By 1943, he said, German industry probably could not have matched American or Soviet production regardless of design. But if Germany had emphasized operational reliability from the start, “we would have lost fewer aircraft to accidents and mechanical failures. Our fighters would have been more effective for longer.”

The production numbers tell the rest. The United States built over 15,600 P-47s. At peak output, one Thunderbolt rolled off the line roughly every hour. Germany, under bombing and resource constraints, produced about 36,000 single-engine fighters of all types during the entire war. And far fewer of those were reliably available at any given moment.

In his memoir, Luftwaffe Test Pilot, Lerche described in detail his encounters with Allied aircraft and what they revealed about differing philosophies. His evaluation of the P-47 highlighted that its real strength was not in any single performance metric, but in design decisions that made it an ideal weapon for an industrial war fought at scale.

Germany entered the war as if it were still 1914–1918, believing in elite pilots and superior machines. The United States entered it as an industrial giant, planning to outproduce, outlast, and out-sustain the enemy.

German fighters like the Bf 109 and Fw 190 were excellent, even brilliant, machines in isolation. But they were thoroughbreds that became harder and harder to feed and stable. The P-47, the “flying milk bottle,” just kept going. It flew from muddy strips. It took punishment. It came home. It could be fixed by ordinary mechanics and flown by well-trained but not superhuman pilots. And there were always more.

Hans-Werner Lerche saw that reality in November 1943 when he taxied out in a captured Thunderbolt. He understood, immediately, that this strange-looking American brute was not built for airshows or test records. It was built for war.

And in a long, grinding war, the side that can keep fighting longest usually wins.

News

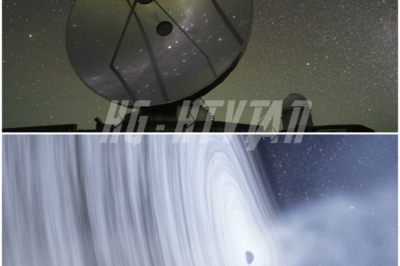

Half the universe was missing… until now

The “Missing” Half of the Universe Until recently, half of the ordinary matter in the universe was missing—hidden, or at…

How did they actually take this picture?

This is an image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, known as Sagittarius…

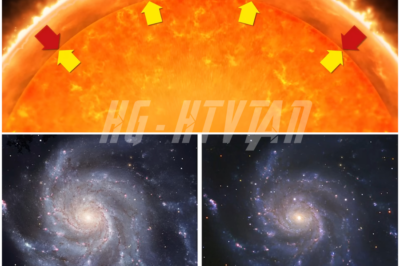

What would actually happen if a star exploded near Earth?

The closest star to us is, of course, the Sun. It’s not going to explode, but if it had about…

Was General George S. Patton, America’s most famous WWII general, murdered in December 1945? And why?

It’s no exaggeration to say that George S. Patton was one of a handful of World War II generals whose…

General George. Patton was a dedicated and controversial soldier.

In December 1944, snow blanketed the battlefields of the Western Front. Exhausted Allied soldiers believed, and many generals quietly agreed,…

Japanese Pilots Laughed At America’s ‘Impossible’ Smart Shells, Until VT Fuses Shot Down 5 Out of 6

August 1943, somewhere in the Solomon Islands aboard the USS San Diego, Lieutenant Commander James Russell, chief gunnery officer, stood…

End of content

No more pages to load