Christmas Eve, 1944: The Day the Second Panzer Division Died

Christmas Eve, 1944.

Deep inside the frozen woods of Belgium, Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert stood beside his command half-track, a flashlight clenched between numb fingers as he studied a creased, mud-stained map. Snow dusted the pines around him. The night was bitter, silent, still.

And yet, on paper, Lauchert was on the verge of doing the impossible.

His Second Panzer Division—veterans of Kursk, Normandy, and three years of brutal Eastern Front combat—had punched sixty miles through American lines in just eight days. They were now only four miles from the Meuse River, the last natural barrier before the open roads to Antwerp. If they reached it, the entire Allied front could split in two.

Behind Lauchert were three German armies—200,000 men—thrown into Hitler’s last great gamble in the west. And at the tip of that spear were his Panthers: sixty tons of sloped armor, long-barreled 75mm guns, and crews as seasoned as any in the Wehrmacht.

But by dawn on Christmas Day, Lauchert would discover that his division wasn’t being defeated by American tank crews, or infantry, or generals.

It was being destroyed by an enemy his training had never prepared him to fight.

An enemy made of factories.

**December 16, 1944 – 05:30 Hours

The Ardennes Erupt**

Eight days earlier, the stillness of the Ardennes forest had shattered under the roar of 1,400 German artillery pieces— the largest barrage on the Western Front since D-Day. The American lines, held by inexperienced and exhausted divisions resting after the hell of the Hürtgen Forest, dissolved in shock and confusion.

Lauchert’s Second Panzer Division, part of General Heinrich von Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps, surged forward. The mission was simple:

Break the American 28th Infantry Division.

Race to the Meuse bridges at Dinant.

Cross before the Americans could destroy the spans.

Drive north to Antwerp.

Speed was everything. German synthetic fuel plants had been bombed to rubble; the offensive could only work if captured American fuel depots filled the tanks of the Panthers.

The first 48 hours went perfectly. By December 18, the division had advanced thirty miles. By December 20, they bypassed Bastogne to the north and pressed toward the Meuse.

The men moved with the confidence of veterans. These weren’t the green, desperate replacements filling other German units in late 1944. These were survivors—men who’d learned to exploit every gap, move with speed, and strike before the enemy could react.

But hidden beneath that confidence was a problem Lauchert could not yet see—one that would soon become fatal.

His division was running out of fuel.

The Fuel Crisis

German plans assumed they’d seize American fuel depots at places like Stavelot and Malmedy. But American engineers, retreating with discipline, destroyed or evacuated every depot before the Germans arrived.

When Kampfgruppe Peiper reached Stavelot, they found the enormous depot empty—three million gallons of gasoline gone. Panthers, Tigers, half-tracks—burning through 1.5 gallons per mile—simply stopped.

Lauchert faced the same disaster. By December 22, the weather cleared and he resumed his advance, but every mile stretched his fuel lines thinner and thinner. The narrow forest roads behind him clogged with trucks trying to bring fuel forward.

And then the skies opened.

December 23 – The Return of Allied Air Power

For six days, fog had grounded Allied aircraft. That fog was Germany’s greatest ally, shielding their movements from the sky that had punished them since Normandy.

But on December 23, the clouds broke—and with them came the fighter-bombers.

P-47 Thunderbolts.

Seven tons of engine, guns, bombs, and rockets.

They came in waves—dozens, then hundreds—hunting anything that moved on the forest roads. Fuel trucks exploded in sheets of flame. Columns of vehicles became charred wreckage. The lifeline of Lauchert’s division was being cut in real time.

But the forward elements didn’t know yet. They pushed west.

And on December 24, they reached the village of Celles—just four miles from the Meuse.

They could see the river valley.

Victory looked close enough to touch.

They had no idea it would be the place where the entire division died.

The American Response: Hell on Wheels

Major General Ernest Harmon, commanding the U.S. 2nd Armored Division—“Hell on Wheels”—received urgent orders:

Stop the German spearhead at Celles.

Do not let them reach the Meuse.

And Harmon had everything Lauchert lacked:

Fuel.

Ammunition.

Clear skies.

An unlimited supply chain.

The Second Armored Division rolled out with 390 tanks—mostly Sherman M4A3s. On paper, the Sherman was inferior to the Panther. German crews mocked it as a “Ronson”—a cigarette lighter—because it ignited so easily.

But Harmon didn’t intend to fight fair.

Christmas Morning – The Trap Closes

At 0900 on Christmas Day, Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division attacked from the north and east. They didn’t charge the Panthers head-on. They maneuvered through woods, used terrain to close the range, struck from flanks, and called in air support.

Above them, P-47s and P-38s swarmed the sky, directed by forward air controllers on the ground.

The Panthers, low on fuel and unable to maneuver, were reduced to stationary turrets. Lauchert, monitoring the battle from headquarters, received panicked reports:

American armor attacking from multiple directions.

Air power everywhere.

Fuel gone.

Movement impossible.

This wasn’t a tank duel.

It was a systematic annihilation.

Sherman platoons advanced, fired into the Panthers’ flanks, and withdrew before German gunners could traverse. If a Panther tried to reposition, Thunderbolts hit it with rockets. If German infantry tried to set up anti-tank teams, American artillery obliterated them.

By noon, the German spearhead was collapsing.

By early afternoon, it was dying.

Lauchert Sees the Truth

At 1320, Lauchert lifted his binoculars toward the northeast tree line.

And froze.

American armor—at least a battalion—was moving toward Celles from three directions. His operations officer began counting:

Ten Shermans.

Fifteen.

Twenty.

Thirty.

Forty.

Forty Sherman tanks in the first wave alone.

And more behind them.

This wasn’t a probing attack.

It was a deliberate, overwhelming strike by a full American armored combat command sent specifically to destroy the Second Panzer Division.

At 1435, the first firefight erupted. A Panther killed a Sherman; the turret blew skyward. But the Americans didn’t flinch. They spread out, returned fire, targeted vision slits and tracks, not the front armor.

Lauchert listened as his radio operator reported:

“Three Shermans destroyed.”

Pause.

“But they keep coming.”

This was not tactics anymore.

This was arithmetic.

America built 2,000 Shermans per month.

Germany built 385 Panthers.

The Americans could lose three tanks for every Panther they killed—and still win decisively.

And they knew it.

The Death of the Spearhead

By 1510, Lauchert realized the truth every commander fears: the division was finished.

Seventeen Panthers destroyed or immobilized.

Ammunition nearly gone.

American forces encircling Celles.

Thunderbolts diving again and again.

At 1535, he gave the order no Panzer commander ever wants to give:

Destroy what cannot be moved.

Crews set thermite grenades in engine blocks. Engineers wired demolition charges to hulls. Young lieutenant tank commanders climbed from their Panthers, placed the grenades, and walked away as white-hot fire devoured their machines.

By dusk, the spearhead was gone.

By nightfall, Lauchert retreated with 140 men and four operational Panthers.

He had begun the day with 800 men and forty-two armored vehicles.

The Americans reported destroying or capturing eighty-two German armored vehicles in the Celles pocket.

The Collapse of the Offensive

Three days later, Lauchert was summoned to Field Marshal Model’s headquarters. Model looked ten years older.

He wanted an explanation for Celles.

Lauchert described the overwhelming American armor, the complete enemy air superiority, the fuel situation.

Model interrupted.

“Could your Panthers kill their Shermans?”

“Yes,” Lauchert replied quietly. “We destroyed at least thirty.”

Model leaned back.

“And they kept coming.”

It wasn’t a question.

It was the truth.

The Americans had lost more tanks in the first week of the Bulge than Germany had destroyed in the entire summer of 1944—yet American tank strength was increasing.

How do you fight an enemy like that?

No one in the room had an answer.

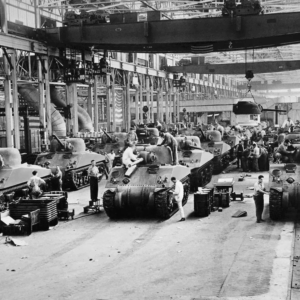

The Industrial Reality

By January 1945, the numbers became impossible to ignore:

1944 Production

— 17,500 Sherman tanks vs. 6,000 Panthers and Panzer IVs

— 96,000 American aircraft vs. 40,000 German

— 2.3 million American trucks vs. German reliance on horses

Replacement Panthers for Lauchert’s division: seven.

Crews: barely trained.

The offensive had failed long before the first Sherman appeared through the trees. It had failed in the factories of America.

Lauchert’s Judgment

After the war, in a British POW camp, American historians asked Lauchert:

“When did you know the offensive had failed?”

His answer was precise.

“1420 hours, December 24.

When I counted forty Sherman tanks advancing, and knew that behind them were forty more, and behind those forty more again. We could destroy them all day. They would still keep coming.”

Conclusion: The Day Industrial Power Crushed Tactical Skill

The Battle of Celles lasted three hours.

It destroyed the Second Panzer Division.

It marked the farthest point of the German advance.

It ended the last German offensive in the west.

But its real meaning was simpler:

It was the day tactical excellence met industrial reality.

And industrial reality won.

The Americans didn’t need better tanks.

They just needed more tanks.

And on a frozen afternoon four days before Christmas,

that was enough.

News

“You should’ve brought food from home, there’s bread on the table already,” my mom told my daughter in front of the whole family, then turned and beamed while my sister ordered extra tomahawk steak, wine, and fancy desserts — I just sat there like the ever “reasonable” daughter, until I ordered my kid a plate of pan-seared scallops, asked the waiter to move the entire bill onto my mom… and quietly kicked off the counterattack that would finally make them pay for their own favoritism for the first time.

The host stand was trimmed with fairy lights and a tiny enamel American flag pin that winked every time the…

“My ex-wife now only deserves some construction worker” – I bragged arrogantly to my friends before driving my BMW to the wedding just to laugh in her face. Little did I know that the moment I saw the groom standing on the altar, I froze, quietly turned my car around, and drove away in tears.

By the time the ice in my glass of sweet tea melted into a pale swirl, the little ceramic mug…

‘The House Is Ours Now. You Get Nothing,’ my daughter-in-law boasted at dinner. Her smile vanished when I calmly told her to explain the truth.

The cranberry sauce was still warm in my hands when my husband destroyed thirty-five years of marriage with seven words….

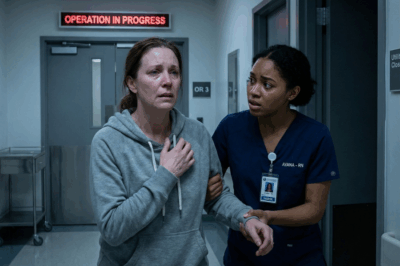

I rushed to the operating room to see my husband, but a nurse grabbed my arm: “Hide now — trust me, it’s a trap.” Ten minutes later, I saw him… and everything made sense.

It happened the night the sky decided to weep for me. The rain wasn’t just falling; it was hammering against…

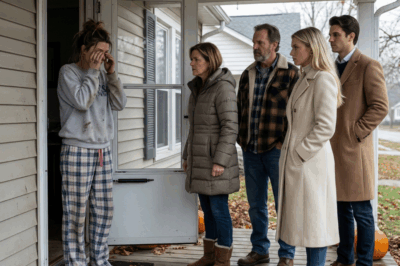

My Mom Said I Wasn’t Welcome at Thanksgiving Because I’d Embarrass My Sister’s Boyfriend. I Hung Up. The Next Day They Came to My Door—And Her Boyfriend Spoke Words That Changed Everything.

My parents cut me from Thanksgiving with the casual indifference of someone trimming fat from a steak. There was no…

My Future MIL Told Me to Quit My Job and ‘Serve Her Son’ — Then the Manager Called Me Chairwoman

The crystal chandeliers of The Golden Spoon, the flagship establishment of the city’s most prestigious dining empire, cast a warm,…

End of content

No more pages to load