No one who lived through May 8th and 9th, 1945, ever forgot what those days felt like. The war that had consumed an entire generation officially ended for Germany on the evening of May 8th, when the act of unconditional surrender came into force at 23:01 Central European Time. But anyone expecting the following morning to bring silence, clarity, or peace quickly discovered otherwise. The first day after the war ended was not one of celebration. It was a moment of suspended reality—an entire country caught between collapse and survival, between guilt and relief, between ruins and the first faint idea of a future.

Imagine waking up to a world where your government no longer exists. The army has disintegrated. The police have vanished. The nation you lived in yesterday has ceased to function overnight. That was Germany on the first day after World War II. A modern industrial society had collapsed into something resembling a vast refugee camp stretched across a landscape of smoking ruins.

For millions, the morning of May 9th began with no clear sense of what had happened. Most Germans no longer had working radios; many had been destroyed in bombings, others confiscated or silenced in the final days of the Reich. Newspapers weren’t printing. Trains weren’t running. Telephone lines were cut. Rumors travelled faster than facts. Some people heard about the surrender from soldiers; others saw notices the Allies had posted during the night. Many simply stepped outside and realized the shooting had stopped.

A Terrifying Silence Over a Destroyed Nation

The silence was the first strange thing people noticed. After years of air-raid sirens, artillery fire, collapsing buildings, and the constant drone of aircraft, the quiet felt unnatural—almost threatening.

Cities that once held hundreds of thousands now resembled enormous graveyards of stone and twisted steel. Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, Cologne, Munich, Frankfurt—each looked as though it had been erased and crudely redrawn in rubble. In Berlin, where the fighting had ended just a week earlier, entire districts were burned-out shells. The few surviving apartments were overcrowded with families, refugees, and wounded soldiers. People slept on broken furniture, in stairwells, in cellars still blackened from fire. Water pumps were damaged, electricity unreliable, and the smell of smoke lingered everywhere; ruins continued smoldering long after battle ended.

On that first day after the war, twenty million Germans were on the move—fleeing Soviet forces, searching for lost family members, or wandering from one town to another in hopes of finding food or shelter. Roads filled with endless streams of people pushing carts, bicycles without tires, baby carriages filled not with children but with blankets, pots, and whatever scraps of life they had saved. Many had walked for weeks; some for months.

Hunger, Collapse, and the Fight for Survival

Hunger was immediate. Food distribution had collapsed completely. Some people survived by scavenging abandoned army depots or salvaging supplies from ruined homes. Others traded jewelry, clothing, or tools for a handful of flour or a few potatoes. Children dug through ruins for anything edible—burned grain, old canned goods, even animal feed. No one knew when Allied authorities would organize supplies, and many feared starvation more than anything else.

For German soldiers, the first day after the war was a mix of humiliation, relief, and fear. Most discarded their uniforms to avoid arrest. Some walked home in stolen or traded civilian clothes. Others limped along roads wearing torn boots, bandaged with pieces of cloth. Surrender meant survival, but also uncertainty. Those captured by the Soviets expected harsh treatment—and many were right to fear it. Others tried to surrender to American or British forces, hoping for better conditions.

Across Germany, the Allies were not yet administrators; they were an occupying force that had just defeated a brutal enemy. Soldiers patrolled streets with weapons ready. Curfews were enforced. Armed checkpoints appeared at major intersections. In some cities, German civilians were ordered to bury bodies still lying in the streets or to clear rubble. The Allies, overwhelmed by destruction and millions of displaced people, were unprepared to instantly restore order.

A Landscape of Fragmented Emotions

Emotionally, the day defied easy description. There was no single feeling that united everyone. Instead, there was a fragmented landscape of reactions.

Some Germans felt deep shame when confronted with the consequences of Nazi rule. Others felt anger or denial, refusing to believe the war was truly lost. Many felt only exhaustion—a fatigue so complete that they could barely think beyond the next hour. And some, especially young people who had known only Nazi propaganda and war, felt something unexpected: relief that the nightmare had finally ended.

But the most pervasive emotion was uncertainty. No one knew what the Allies planned to do with Germany. Would the country be dissolved? Would everyone be punished? Would food return? Would families ever be reunited? Entire communities asked these questions at once, but no answers existed.

Life on the first day after the war wasn’t about rebuilding, politics, guilt, or ideology. It was about survival—water, shelter, safety, food—and about the faint hope that tomorrow might be less chaotic.

First Signs of a New Reality

Yet, even on that first day, small signs of a future began to appear. Allied troops handed out chocolate and chewing gum to children. Civilians approached soldiers cautiously—not as enemies, but as the only remaining authority. In some towns, church bells rang for the first time in years—not to warn of bombers, but to signal peace. A few people dared to speak openly again, free of the Gestapo’s shadow.

Signs appeared on wood scraps or bed sheets:

We are alive.

Looking for family.

Food needed.

Children safe here.

The Reich had fallen, but life in Germany had not ended. It was beginning again—slowly, painfully, with no guarantees.

The Allies Walk Through the Ruins

As the sun rose higher on May 9th, one of the strangest sights appeared: Allied soldiers walking openly through streets once dominated by Nazi authority and propaganda. For years, the Nazi regime had depicted the Allies as monstrous, cruel, almost inhuman. But when real Allied soldiers appeared—young men barely older than German sons—civilians were stunned. These soldiers looked tired, confused, uncertain about the future.

In the American and British zones, interactions were often tense but rarely violent. Civilians were required to approach with hands visible, obey curfews, avoid sudden movements. Yet small moments stood out: an American giving water to an elderly man, a British sergeant helping a woman lift rubble so she could enter her damaged home.

In the Soviet zone, things were far more complicated. The Red Army had suffered over twenty million dead. Many soldiers carried rage and trauma. Violence, assaults, and looting were widespread. Civilians hid women and girls in cellars or behind false walls. Even so, some Soviet officers protected civilians and organized food distribution. But fear dominated life in the east.

A Nation Without Police, Currency, or Direction

Across Germany, the police had vanished. Many towns had no functioning authority except perhaps a local mayor—if he had not fled. Some communities organized informal patrols. Others did nothing.

Money lost its value. People bartered with cigarettes, coffee, sugar, or anything useful. An American cigarette could buy a meal. Chocolate could buy clothing. Markets sprang up in ruins where blankets displayed whatever people had left.

Identity itself was shattered. Without government symbols—no swastikas, no Hitler on the radio—Germans felt as if something enormous had been ripped out of their lives. Even those who hated Nazism wondered what came next.

In some places, Germans tore down Nazi symbols. In others, Allied soldiers forced civilians to remove them. Some towns were marched past concentration camp corpses to witness the truth of the regime. This was the beginning of confronting the Holocaust—not yet organized denazification, but blunt exposure.

Hunger and the Daily Fight to Survive

Hunger shaped everything. Women lined up outside bakeries with little hope. In towns with no intact shops, people gathered wherever Allied trucks might appear. The average calorie intake was around 1,000 calories—barely enough to survive. On that first day, many ate far less.

People cooked thin soups from whatever vegetables they could find. Nettles, dandelion leaves, scrap grains. Furniture became firewood. Pots simmered over fires built on bricks pulled from collapsed buildings.

Yet even amid hardship, small moments of hope surfaced.

Children, Letters, and Small Markets of Hope

Children, who had grown up knowing nothing but war, explored ruins with awe. They collected colored glass, metal fragments, burned toys. They played, even though unexploded bombs were everywhere. For them, silence felt magical.

Adults found hope in reunions. Someone discovered a missing neighbor alive. Someone received a letter carried by travelers. The words I am alive were priceless.

Small markets formed among ruins. A woman traded a coat for onions. A soldier traded boots for bread. Survival wrote its own rules.

Fear and the Fragile End of War

As the day progressed, fear of mass arrests grew. People hid uniforms, burned documents, destroyed evidence of Nazi affiliation. Smoke from burning papers drifted over ruins. Many believed the Allies might execute anyone connected to the regime.

Fear shaped countless actions—but no mass executions came.

Despite everything—the hunger, fear, destruction—there was one undeniable truth: the war was over.

It almost didn’t feel real. Nazi leaders had promised victory until the end. Hitler demanded loyalty to the last breath. Then suddenly it all disappeared into silence.

The first day after the war wasn’t peaceful, joyful, or hopeful. But it was the first day in twelve years when Germans could imagine a future without Hitler. Children slept without fear of bombers. Women walked outside without checking the sky. The world shifted—not into rebuilding, but into the possibility of rebuilding.

Nightfall — A Heavy, Uncertain Darkness

When night came, darkness felt heavier than wartime blackouts. During the war, darkness had been ordered, a defensive measure. Now it was the absence of power, the absence of structure, the absence of a functioning nation.

Cities lay in shadow except for a few candles in broken windows or distant Allied campfires. Families sat quietly in surviving rooms, speaking softly, struggling to process the day.

Children asked questions:

What happens now? Where do we get food? When will the soldiers go home?

Adults asked harder questions: What had they believed? Ignored? Allowed?

But most wanted only safety. To sleep without more chaos.

Rural Refuge and Fear

In rural areas, calm replaced destruction. Farmers inspected fields, knowing they would soon feed entire starving regions. Villages served as temporary sanctuaries for refugees fleeing ruined cities.

Yet even there, fear persisted. Soviet columns crossed rural roads. Rumors of violence spread. Families hid daughters. People locked doors at night—something rare before the war. In the western zones, villagers listened nervously for Allied vehicles unsure what each arrival meant.

As darkness thickened, Germans realized how isolated they truly were. The Reich had abandoned them long before surrender. Hitler was dead. Goebbels dead. Himmler fled. The regime that promised a thousand-year kingdom collapsed after twelve.

Shared Food, Shared Suffering, Shared Humanity

Relief mixed with guilt. Shame mixed with fear. Some cried without knowing why. Others felt nothing at all.

But something else emerged, too—kindness.

Neighbors shared food: jam, potatoes, bread. With no currency, Germans created improvised safety nets. Human decency, worn down by dictatorship and war, resurfaced in small acts.

Allied troops helped prevent total collapse: American field kitchens, British rations, French administrative order, Soviet commanders enforcing discipline.

It was imperfect, but without them, chaos would have been far worse.

A Quiet Night — The First in Years

Throughout the night, the sky remained quiet. No sirens. No bombs. Just the distant rumble of Allied trucks and the soft murmur of thousands trying to sleep in ruins. For many children, it was the first peaceful night of their lives.

Adults found the silence unsettling.

A New Reality Dawns

On May 10th, the second day of peace, Germany remained a country without government, without functioning cities, without certainty. But something fundamental had changed: for the first time in years, people awoke simply to daylight—not to propaganda, orders, or explosions.

In the following weeks, the Allies established zones, food systems, and curfews. Families searched for each other. Refugees continued arriving. The Holocaust became impossible to deny. Cities began clearing rubble. Reconstruction would take decades. Democracy would take generations.

But the seed of all these changes was planted on that first day after the war—a day defined not by triumph, but by survival. Not by clarity, but by confusion. Not by celebration, but by the fragile beginning of peace.

It is tempting to view May 9th, 1945, as the end of tragedy. In truth, it was the start of a long, painful, complicated rebirth. The people who lived that day did not know their country would rise again, or that Europe would reconcile, or that Germany would one day become a symbol of stability and democracy.

All they knew was that the guns had stopped.

The bombs had fallen silent.

And life—broken, shaken, but still alive—had to continue.

Germany on the first day after World War II was a place suspended between destruction and renewal. A place where silence replaced bombs. A place where strangers shared the last pieces of bread.

News

How One Engineer’s “Ridiculous” Wing Tape Made Hurricanes Dodge Bullets They Couldn’t See

September 15th, 1940.11:47 a.m.23,000 feet above Kent, England. Squadron Leader Douglas Bader banks his Hawker Hurricane hard left just as…

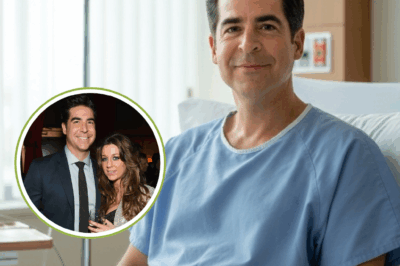

🔥 “I NEED YOU BY MY SIDE.” — JESSE WATTERS’ POST-SURGERY MESSAGE LEAVES FANS IN TEARS 😭💬 No studio lights. No script. Just Jesse Watters, finally speaking after weeks away — and what he said hit harder than anyone expected. He confirmed the surgery is behind him… but the battle isn’t. His words were simple, but full of weight: “Healing takes time… and I need you by my side.” Why are longtime viewers calling it the most human moment of his career? What hasn’t been shared publicly yet? And how is his recovery changing everything about how he sees the road ahead? This wasn’t just an update. It was a turning point. 👇

HEART OF THE FIGHT: Jesse Watters Speaks After Surgery in Powerful Message That Grabs the Nation It had been weeks…

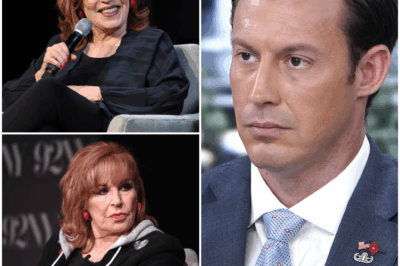

🔥 “THEY TRIED TO DESTROY ME ON LIVE TV.” — JOHNNY JOEY JONES HITS ‘THE VIEW’ WITH $50M LAWSUIT 😱⚖️ What started as a throwaway joke on The View just triggered a legal war that could shake daytime TV to its core. Fox News veteran Johnny Joey Jones has filed a $50 million lawsuit, accusing Joy Behar and the show’s producers of orchestrating a live-TV “assassination” of his character. But what exactly did they say — and why is Jones claiming he has names, receipts, and proof it wasn’t accidental? Insiders say ABC is rattled, lawyers are circling, and the next court filing may expose more than anyone expected. This isn’t just defamation — it’s personal. 👇

In a case that may define the boundaries of media commentary and military respect, Marine veteran Johnny Joey Jones has…

At My Baby Shower, My Sister Gifted Me a Broken Stroller — Then My Husband Pressed a Button Everyone Missed

Some moments change everything. This is the story of Cali, a woman who had struggled with infertility for years before…

Our Son and Daughter-in-Law Locked Us in the Basement of Our House — I Panicked, but My Husband Leaned In and Said, ‘Don’t make a sound… they don’t know what’s hidden here.’

The basement door slammed shut above us, a violent crack of wood against frame, followed immediately by the distinctive, metallic…

My Beautiful Christmas Tree Was Stolen by My Landlord, and I Responded Harshly

A Christmas Tree Full of Surprises After months of careful saving, Maria Hernandez, a devoted single mother, had thoughtfully organized…

End of content

No more pages to load