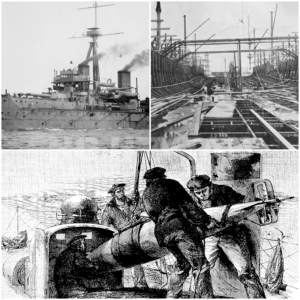

Every now and then, an invention comes along that shocks the world and changes the way things are done forever. Back in the 1800s, it was the steam engine that launched the Industrial Revolution. Today, the closest equivalent might be artificial intelligence—don’t worry, I’m not an AI version of Mike Brady yet. But in 1906, something happened that transformed naval warfare forever when a new class of ship was introduced, a vessel so radical and so revolutionary that every battleship on Earth became obsolete almost overnight. Her name was HMS Dreadnought, a word meaning “fear nothing.” The Royal Navy has always had a talent for choosing intimidating names, but Dreadnought brought changes to battleship design that would influence naval architecture for decades. It’s ironic that a ship so revolutionary would, within a few decades, be overshadowed by the rise of the aircraft carrier. Still, when she hit the water in 1906, Dreadnought was the undisputed queen of the seas.

To understand why Dreadnought was such a big deal, we have to look back to the 1700s and 1800s. For centuries, warships followed a simple formula: enormous floating fortresses of pine and oak, mounting as many cannons as their decks could handle. Ships from Lord Nelson’s day looked remarkably similar to those from the age of Sir Francis Drake. They relied entirely on sails, meaning their speed and maneuverability were at the mercy of the wind. Their cannons had ranges of only a few hundred yards and fired solid shot or special ammunition intended to tear down an enemy’s rigging. Because of these limitations, naval battles consisted of ships closing to nearly point-blank range, unleashing roaring broadsides, and sending boarding parties to fight hand-to-hand. If you’ve seen Master and Commander, you’ve had a taste of what those brutal engagements were like.

But change was coming. In the early 1800s, the steam engine emerged, and warships were no longer bound to the whims of the wind. Suddenly, ships could propel themselves regardless of weather, turning the stagnant periods of calm seas into relics of the past. This shift also made new advances possible in iron—and eventually steel—construction. Within a few decades, warships went from wooden hulks to vessels that, despite looking similar externally, were fundamentally transformed inside. They were still armed with old cannons at first, but mid-century innovations—such as rifled gun barrels and breech-loading mechanisms—transformed naval gunnery entirely. Rifling allowed shells to spin and travel farther and more accurately. Breech-loading improved safety and rate of fire. The next leap came when engineers mounted these guns in rotating turrets, allowing nearly full-circle firing capability. This eliminated the need for ships to align their entire hull toward their target.

Early turret ships had problems, especially in the British Royal Navy, which approved some questionable designs. Eventually, though, navies refined the formula, and by the late Victorian era, battleships were steel-armored, steam-powered giants with turrets firing in multiple directions. These ships were far more advanced than their predecessors, but ironically, they still had little real combat experience. Designers could only guess what their new creations were truly capable of.

They got a preview during the American Civil War, when the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia hammered away at each other without causing decisive damage. The lesson was clear: guns now needed to outmatch armor, and the race between firepower and protection escalated rapidly. By the late 1800s, battleships could fire at ranges of 6,000 yards and dominated the seas—until the torpedo changed everything.

Torpedoes, carried by small, fast torpedo boats, threatened to turn lumbering battleships into helpless targets. The torpedo boat was cheap, fast, and dangerous. A single shell could destroy it, but if dozens swarmed a battleship and launched their torpedoes, they could overwhelm even the mightiest vessel. This arms race pushed battleship designers to rethink everything. Battleships needed to be faster, sleeker, equipped with fewer but larger guns firing at long ranges, and protected from torpedo attacks by staying further away.

Visionaries, including Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti, began advocating for an “all-big-gun battleship,” armed entirely with large-caliber guns and escorted by smaller ships handling secondary duties. Cuniberti envisioned a fast, heavily armed, heavily armored vessel displacing 17,000 tons and carrying twelve 12-inch guns. His ideas were rejected in Italy but published widely, influencing naval thinkers across the world.

Around the same time, the British Royal Navy was also observing the Japanese fleet’s performance in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher recognized two key lessons: the destructive power of 12-inch guns and the decisive importance of speed. Battleships needed to maneuver aggressively, strike at long range, and avoid torpedo attacks. Britain also had a crucial technological advantage: the steam turbine engine, perfected by engineer Charles Algernon Parsons. Turbines were lighter, more efficient, and vastly faster than traditional triple-expansion steam engines. Parsons stunned the world in 1897 when his turbine-driven test craft, Turbinia, darted through a naval review like a sea-going lightning bolt, proving the superiority of the design.

Fisher seized upon this technology for his new battleship. The turbine engines saved 1,100 tons of weight and delivered unprecedented speed. Combined with a sleek, hydrodynamic hull, Dreadnought was designed to reach nearly 22 knots—astonishing for a battleship of her size.

Her armament was equally revolutionary. Gone were the confusing mixes of large and medium guns. Instead, Dreadnought mounted ten 12-inch guns in five twin turrets: one forward, one aft, and two on the beam capable of firing across the deck. A ship crossing the enemy’s “T” could unleash eight heavy guns forward—double the firepower of existing battleships.

Construction began in October 1905, and the ship was launched just four months later, built at a breakneck pace using standardized steel plating and streamlined labor. The Admiralty intended her speed of construction to prove Britain’s industrial dominance.

When Dreadnought launched in February 1906, she immediately rendered every battleship on Earth obsolete. Journals like Jane’s Fighting Ships boasted that her capabilities equaled two or even three older battleships combined. Not everything was perfect—she sat low in the water, and her crew accommodations were cramped—but her innovations were undeniable.

Her arrival triggered an arms race across Europe, especially in Germany, where Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz pushed for a massive naval buildup. Germany increased naval spending dramatically, committing to building dreadnought-class ships of its own. Pre-dreadnought battleships—built before 1906—were now outdated overnight.

Despite her revolutionary design, Dreadnought’s career was surprisingly uneventful. She rammed and sank a German submarine during World War I—something even the ocean liner Olympic managed—but missed the monumental Battle of Jutland due to scheduled maintenance. Most famously, she fell victim to a 1910 prank when British university students disguised themselves as Abyssinian princes and toured the ship while shouting “Bunga! Bunga!” Years later, after sinking U-29, Dreadnought reportedly received a telegram saying the same phrase.

By the end of World War I, Dreadnought, once the most advanced warship in the world, was relegated to coastal defense duties alongside the very pre-dreadnought ships she had rendered outdated. The battleship as a class would soon share her fate. In World War II, aircraft proved that even the mightiest battleships—Repulse, Prince of Wales, Bismarck, Yamato, Musashi—could be sunk by swarms of planes.

Even so, Dreadnought did her job brilliantly. She combined multiple innovations into a single design that completely rewrote naval warfare. Her existence triggered one of history’s greatest naval arms races, shaping the world on the eve of World War I. For that, she deserves recognition. Job well done—and, as history would later joke, “bunga bunga” indeed.

News

My Family Always ‘Forgot’ to Invite Me to Christmas — This Year, My Revenge Came Wrapped in Snow

I bought the house for silence, but the first photo I posted of the deck went viral in the family…

They Skipped My Son’s Surgery but Asked Me for $10,000 for a Dress — I Sent $1 and Said, ‘Buy a Veil.’ The Next Morning, Karma Knocked

The Day I Stopped Being the Family ATM Sometimes it takes a crisis to reveal who your family really is….

— Egor? Your wife is at my place; she needs a change of clothes. Really needs it. She’s sitting in my bathroom with nothing on.

Violetta turned off the ignition and grabbed her phone on the second ring. “Mr. Grigory Sergeyevich?” “My golden goose, turn…

The Bismarck – How the World’s Most Feared Battleship Lasted Only Eight Days at Sea

At 2:48 in the morning on May 24th, 1941, a British naval officer spotted something through his binoculars that made…

⚠️ “CITIZENSHIP UNDER REVIEW?” — REPORTS SAY ILHAN OMAR COULD FACE DEPORTATION IN UNPRECEDENTED MOVE 😳🔥 Washington is bracing for impact after explosive reports claim Rep. Ilhan Omar may be under formal investigation that could lead to the revocation of her U.S. citizenship — and possible deportation. No official confirmation yet, but whispers inside DHS and State suggest something serious is unfolding behind closed doors. Could this really happen to a sitting member of Congress? What triggered the probe? And why are legal experts warning this case could set a dangerous new precedent? Political lines are hardening, and the phrase “uncharted territory” is coming up more than ever. The silence from Omar says even more. 👇

Washington, D.C. — Reports exploded across fringe websites and hyperpartisan outlets this week claiming that Rep. Ilhan Omar was under…

My sister tried to frame me with a $4,000 necklace. I exposed her. My parents took her side — so I blocked them. Weeks later, a text arrived that flipped everything.

My parents called it “just a get-together” when I wasn’t invited to my sister’s tenth anniversary party. I showed up…

End of content

No more pages to load