Our mission that day was simple: go talk to a suspected bomb maker. Nothing unusual about that. As we moved through the area, there was this older man walking around, watching us. That in itself wasn’t strange—curiosity was normal. But it became less normal when he kept coming back. He’d walk off, then return, then leave again, only to come back and watch some more. It was obvious he was trying to figure out what we were doing.

Then we walked right in front of the older man’s house—only this time he was nowhere to be found. Immediately, red flags went off in my head. This guy had been so interested in us, and now he’d vanished. I glanced back and told the team, “Hey, the old guy is gone. Be ready. Something’s about to happen.”

About thirty seconds later, I saw him again—standing behind a wall, maybe twelve feet from me. He looked like any other civilian. I went back to scanning with my Vallon metal detector, doing my job. Then, out of the corner of my eye, I caught him move fast. I squared up to him, and by the time I faced him, he had already pulled a rifle from behind his back and started spraying. He was way too close to miss.

He hit me ten times.

Growing Up and Joining the Army

I was born and raised around Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky. Military service existed in my family—an uncle in Vietnam, another before him. So, yeah, absolutely, it was part of our history.

I enlisted in the Army in 2010. I joined because I always felt like I needed to be part of something meaningful—something bigger than myself. Growing up, every movie, every TV show I watched about war always centered around the Army. That was what I thought a soldier was. When the time came, there was no other choice for me. I was twenty-one—the “old man” in basic training, which still sounds ridiculous, but in basic, twenty-one is old.

Basic training itself went smoothly. The military isn’t complicated at first—just listen and do what you’re told. You’re told what to wear, when to eat, where to go. The hard parts come later.

I knew from day one what I wanted: to fight. That, to me, was what a soldier did. So I signed up for infantry. Absolutely.

Three months after graduating basic, my boots were on the ground in Afghanistan.

Arriving in Afghanistan

I was part of the 4/4 CAB. Our mission was the same as everyone’s in Afghanistan—win hearts and minds, push out the Taliban, try to stabilize the area. We all know how that ultimately turned out.

I was stationed in Kandahar province. And honestly—Afghanistan is a beautiful country. When the poppy fields bloom, it’s stunning. Mountains, desert, fields—it’s gorgeous. If there weren’t things buried in the ground that could kill you, it’d be an incredible place to visit.

The reality doesn’t hit until you get shot at for the first time. Before that, you’re just doing your job—patrols every other day, following orders. Then bullets snap past your head and everything changes. You realize you’re truly in a war zone.

Every patrol was different: sometimes meeting a suspected bomb maker, sometimes talking with a tribal leader, sometimes deliberately drawing fire so drones overhead could observe enemy movements. I served as a Vallon operator—basically a frontline metal-detector guy. My job was to walk ahead of everyone else, scanning for IEDs. At first it terrified me—literally having everyone’s lives in my hands. But with training, I got good at it. Very good. I could distinguish different metals by sound alone.

After I was shot, my friends took over my job. That made losing them even harder.

April 21, 2011 — The Day I Was Shot

The day started like any other patrol. Wake up, eat, gear up, get ready to step outside the wire. We walked for about an hour and a half before we saw the man who would eventually shoot me.

We crossed a water area, stopped to reassess, and that same older man kept walking around watching us. Kids did that all the time, but adults? Not so much. And the way he kept returning made it obvious he was assessing us.

We finally moved on. We walked beside his hut, jumped a wall into a narrow path—what they called a road, but what I’d call a sidewalk. Somehow they drove vans on those things, which is insane. Afghan drivers are either the craziest or the greatest I’ve ever seen.

We passed his house again. He wasn’t there. That’s when I warned the team.

Then I saw him—just behind a wall, twelve feet away. He looked normal. I kept scanning with the Vallon.

Then he moved. Fast.

I squared up to him. He already had the rifle up. He fired a burst. Too close to miss.

Ten rounds hit me—starting at the thigh, four in the hip, then up my torso, and five in the shoulder. Two rounds went through my rifle into my plates, bruising my chest. If my rifle hadn’t been slung across my chest, I wouldn’t be here.

On the Ground — Pain, Fear, and Staying Alive

People say adrenaline kicks in and numbs the pain. They lie. I remember every bit of it. The pain, the shock, the screaming. I remember falling to the ground. His rifle jammed—that’s the only reason he stopped shooting.

I aimed my rifle at him. He saw that and ran. Dropped his gun and bolted. He didn’t realize my weapon was useless—his rounds had destroyed it. When I pulled the trigger, nothing happened.

The smell of my own flesh burning is something I’ll never forget. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

The scariest part wasn’t the pain. It was not knowing where he went. I was sure he’d peek around the corner and finish the job.

I lost so much blood that my vision turned white—like a film covering my eyes. Later, I wondered if that’s what people mean when they talk about “seeing the light.” Parts of my body were shutting down.

I forced myself to stay calm. That’s what they teach you—shock kills.

My guys reached me, cracked jokes to keep me grounded, and it worked. They dragged me back through the water we crossed earlier. They almost dropped me once—I still don’t let them live that down.

Emergency Treatment and a Mysterious Voice

They got me to Kandahar Airfield Hospital. Doctors stuffed gauze into holes, pumped me full of blood, kept me alive. My sight returned slowly. As I lay there saying I couldn’t see, someone bent down—a woman’s voice—and told me, “It’s okay to sleep. We’ve got you. You can let go now.”

I passed out immediately.

Years later, someone who was there told me: there was no woman in that room. I still get chills.

Saving My Arm and the Long Path to Recovery

On the flight to Landstuhl, Germany, they lost pulse in my arm and thought they’d have to amputate. Modern medicine saved it—they took a vein from my leg and replaced the artery. I didn’t know that was possible.

I didn’t understand the extent of my injuries at first. I thought they’d fix me up and send me back to Afghanistan. That’s what I wanted—my whole mission in the Army was taking care of the person to my left and right. The bond you form is unlike anything else.

At Walter Reed, after moving from inpatient to outpatient care, my therapists finally broke the truth to me: this injury would last a lifetime. Unless a miracle happened, I’d never go back to combat.

That realization crushed me. My whole plan had been a twenty-year Army career.

They offered me a list of non-combat jobs. Desk jobs. Non-deployable roles. That wasn’t why I joined. I joined to fight. If I couldn’t fight, what was the point?

That’s when the depression hit. Hard. Eventually, I entered the med-board process and was medically retired.

Life After the Army — Archery, Music, and Healing

Over the next five years, life happened. I had four kids. I competed in archery with the U.S. Paralympic program. Archery became therapy—an escape. Then COVID hit. The world shut down. My escape vanished.

When the world gets quiet, the demons get loud.

One day, desperate for something to hold onto, I picked up the old guitar in the corner. I opened YouTube, learned G, C, Em, and D—four chords that unlock thousands of songs. I learned songs I grew up with, because I knew how they were supposed to sound.

Music became my new escape—my therapy.

Then I realized something: I still had all these emotions, all these memories, all this pain inside me. I needed to get it out before it overflowed. So I learned to write songs—verses, choruses, bridges—again from YouTube.

My right hand is permanently damaged, with almost no feeling. Learning guitar after my injury was painful and incredibly hard. But because I’d never learned before, I didn’t know what I was missing. If I had known how easy it used to be, I probably would have quit.

When the world reopened, I went to an open mic outside Nashville. I played the first song I’d ever learned: Should’ve Been a Cowboy by Toby Keith. It probably sounded awful—but for me, it meant everything. That feeling was magnified a hundred times. Music became purpose.

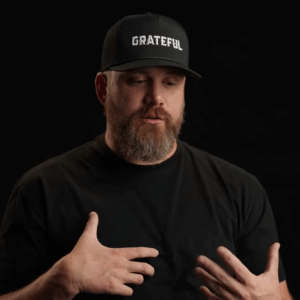

I hope my story helps someone. I hope my songs help someone put the gun down. That’s my goal.

“You Helped Me Stay Alive” — The Moment Everything Changed

I’ll never forget the moment I realized my music mattered. I was in Phoenix, opening for Dave Grohl—my first time ever opening for an artist. Dave is one of the most incredible people I’ve ever met.

I played a song I’d written just two days earlier: How Do You Choose?, about survivor’s guilt and why I’m here when my best friend isn’t.

When I finished, there was silence. I thought they hated it. Then I realized people were consoling each other. That’s when I knew the song meant something. We needed to record it.

The next day, I got a message from a guy who’d been at the show. He said:

“I was going to end it. I was done. I figured I’d go see Dave Grohl one time since the tickets were free for veterans, and then I’d go home and end it. But I wasn’t ready for Scotty. He played How Do You Choose?, and it changed everything. I realized I wasn’t alone. And I decided to keep going.”

That was the moment.

That was the fire.

That was why I do this.

100%.

News

I Covered My Parents’ Mortgage for Years — Only to Watch Them Gift the House to My Sister

The Trust Fund That Revealed Everything The mahogany conference table gleamed under the crystal chandelier as I sat rigidly in…

A Starving Horse, a Hidden Brand, and a Girl Who Vanished Ten Years Ago

The December morning was bitter cold in the Montana hills when Luke Mills spotted what he first thought was a…

My Son Put His Heart Into Making Me Birthday Chocolates — My Simple Reply Set Him Off in an Instant

The Poisoned Gift My son sent me a box of handmade birthday chocolates. The next day, he called and asked,…

I Inherited a Fortune and Lied to My Son About Being Penniless — When I Showed Up With My Suitcases, My Heart Dropped

The Housekeeper’s Secret The doorbell rang at exactly eleven twenty-seven, slicing through the silence I had wrapped around myself…

They Kicked Us Off the Flight — Not Knowing Who Controlled the Airspace

The Power of Silence The air in Terminal 4 tasted of recycled anxiety, burnt coffee, and the sickly-sweet chemical glaze…

One Man Took in Nine Unwanted Baby Girls Back in 1979 — 46 Years Later, Their Bond Defines Family

The Warehouse Discovery Margaret Chen had always prided herself on being the kind of person who noticed details others missed….

End of content

No more pages to load