Part 1 – The Report That Terrified Berlin

I. March 17th, 1943 – The Paper That Shouldn’t Exist

Berlin was gray that morning, the kind of cold that clung to uniforms and glass windows. Inside a paneled office buried within the Abwehr’s headquarters on Tirpitzufer, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris sat at his desk staring at a single sheet of paper that could, if anyone believed it, rewrite the entire war.

The document was unremarkable in appearance—one page, typewritten, standard header. Yet the numbers printed on it were beyond comprehension.

At the bottom, in a clerk’s cramped hand, someone had written a date and a note: Source verified, cross-referenced, multiple confirmations from neutral channels.

The summary read simply:

“United States production capability—Ford Motor Company, Michigan—projected output: one four-engine bomber (B-24 type) per sixty minutes.”

Canaris set his pen down. Around him the office was silent except for the faint hum of the city’s blackout generators. For a long time he didn’t move. He had read hundreds of intelligence reports in his career—raw intercepts, decoded telegrams, field summaries—but none that felt like this.

It wasn’t information; it was a verdict.

Across the hallway, his deputy Colonel Hans Oster was waiting. When Canaris finally opened the door, Oster saw something in his superior’s face he’d never seen before—fear, not of men, but of numbers.

“What is it?” Oster asked quietly.

“If this report is correct,” Canaris said, “the war is over. We just haven’t been told yet.”

II. The Anatomy of a Revelation

The Abwehr had been piecing together fragments of industrial intelligence for months. Agents in neutral countries—Sweden, Switzerland, Spain—were reporting the same improbable rumor: the Americans were mass-producing aircraft the way they once built automobiles. A businessman arriving from Detroit spoke of a factory “so large it has its own weather.” A neutral diplomat in Washington mentioned an assembly line that moved faster than logic. A Swedish engineer whispered that aircraft frames were passing along conveyor belts like tin toys.

At first the analysts laughed. Aircraft manufacturing was a craft, not a process. It required skilled men, precise tolerances, and months of labor.

But as Canaris’s staff cross-checked sources, the laughter stopped. Too many independent reports matched. Too many figures converged.

The location was clear: Willow Run, near Ypsilanti, Michigan.

The company behind it: Ford Motor Company—Henry Ford’s empire now redirected from automobiles to war.

When the first aerial photographs arrived via Swedish intermediaries, the scale defied imagination. A single building sprawled across farmland like a metallic city. Analysts calculated its roof area at nearly 67 acres. The line inside stretched for over a mile and a half, ending in an airstrip where finished bombers could take off directly from the factory floor.

An intelligence officer whispered the number again, almost afraid to say it aloud: “A bomber every hour.”

No one in Europe—not even the Soviet Union’s vast arsenals—had anything close. The Luftwaffe’s largest bomber, the Heinkel He 177, took three weeks to assemble under ideal conditions. Germany’s entire heavy-bomber output for 1942 was fewer than 400 aircraft.

If the American projection was true, Willow Run alone would surpass that in three weeks.

The implication was unspeakable: production had become warfare, and Germany was outgunned before a shot was fired.

III. The Admiral in the Lion’s Den

Admiral Canaris was not a man easily rattled. He had commanded U-boats in the Great War, navigated coups, spied on friends and enemies alike. He was, by temperament, detached. But this report pierced through the professional calm. It wasn’t just about airplanes—it was about ideology.

He requested a private conference with Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe.

The meeting took place three days later inside the Air Ministry’s marble corridors.

Canaris arrived with a leather portfolio containing the Willow Run file—photographs, decoded cables, cross-references.

Göring greeted him with his usual theatrical flourish: gold brocade, manicured nails, and the faint smell of cognac.

“What terrible secrets are you bringing me today, Wilhelm?” Göring quipped.

Canaris opened the folder and slid the report across the table.

Göring scanned the first line, then laughed—an enormous, echoing laugh that bounced off the marble walls.

“A bomber every hour? These Americans! They are good at refrigerators and razor blades, not airplanes!”

The laughter continued until it felt forced. Canaris didn’t smile.

“Reichsmarschall,” he said evenly, “my analysts have verified these numbers from three independent sources. Even our Japanese allies confirm American aircraft output at unprecedented levels.”

Göring waved a jeweled hand dismissively.

“You have been deceived by Allied propaganda. Impossible. No factory could do this. Our own Heinkel plants employ the finest engineers in Europe. Do you think a pack of Negroes and shopgirls in Detroit could outbuild them?”

It was the essence of Nazi certainty: prejudice elevated to policy.

Canaris closed the folder. “If the figures are even half true,” he said quietly, “Germany will be fighting ghosts by next year—ghosts made of aluminum.”

Göring stood, puffing his chest, furious now. “Leave your fantasies to your spies. I have a war to win.”

The admiral saluted and left without another word. In the corridor, an aide whispered, “What did he say?”

Canaris answered flatly, “He laughed.”

IV. Inside the Wolf’s Lair

Getting accurate intelligence to Adolf Hitler in 1943 was an art form bordering on suicide. The Führer’s headquarters—Wolfsschanze in East Prussia—was a warren of paranoia. Bad news was filtered before it reached him; dissent was treason by another name.

Canaris understood this but pressed forward. On April 3rd, 1943, he arranged to include the Willow Run data in a broader strategic briefing on Allied industrial capacity.

When his turn came, he laid out the facts with surgical precision: tonnage, manpower, capital, logistics. At the climax he presented the projection—24 bombers a day from a single facility.

Hitler stared at the numbers, expression unreadable.

Then, slowly, he smiled—a thin, contemptuous smile.

“American exaggerations,” he said. “The Jews in Washington feed them to frighten us.”

Albert Speer, the Armaments Minister standing nearby, said nothing. He later admitted that the figures chilled him.

But silence was survival. To contradict the Führer was to disappear.

The meeting ended with Hitler declaring that German willpower would triumph over “Yankee mechanization.”

Outside, Canaris’s adjutant exhaled in relief.

The admiral did not. He knew he had just witnessed Germany’s obituary being signed—in denial.

V. The Death Sentence in Numbers

Within months, the prophecy began to materialize.

By late 1943, the U.S. Eighth Air Force had grown from hundreds to thousands of heavy bombers. Entire airfields in England were filling faster than German intelligence could update maps. The sky over occupied Europe began to hum.

German field officers wrote back to Berlin in disbelief: “The enemy squadrons multiply as if from the air itself.”

They were not wrong. They were seeing Willow Run’s output in motion.

By February 1944, the campaign known as Big Week commenced—an industrial onslaught aimed at dismantling the Luftwaffe’s own production.

B-24 Liberators, many bearing serials from Michigan, poured across the Reich in daylight waves so thick that anti-aircraft gunners said the sky turned to metal.

Factories vanished. Rail lines twisted. Cities burned.

The same men who had laughed at the idea of “one bomber an hour” now faced entire armadas born from that impossible math.

For every bomber shot down, two more appeared the next week.

The Luftwaffe, bled dry of fuel and pilots, crumbled.

Canaris’s memo from that spring was bleak:

“The enemy’s strength grows geometrically; ours declines arithmetically. This curve ends only one way.”

VI. The Admiral’s Isolation

Truth in Hitler’s Germany was a lonely profession.

By mid-1944, Canaris was under suspicion. His measured reports on Allied superiority were labeled “defeatist.”

The SS and Gestapo began infiltrating the Abwehr, searching for disloyalty.

Every warning he had delivered about industrial imbalance was recast as evidence of treachery.

He kept one note for himself, written in a cipher only he understood:

“They call it faith. I call it blindness.”

When the July 20 plot to kill Hitler failed, the net closed.

Canaris was arrested, his diaries seized.

Among the confiscated files was the Willow Run report—still marked Top Secret – March 1943.

In April 1945, weeks before Germany’s surrender, he was hanged at Flossenbürg concentration camp, stripped naked, strangled with piano wire.

The man who had measured the Reich’s doom in tonnage and labor hours died at the hands of the ideology he had tried to warn.

VII. Arithmetic Wins

When Allied analysts compiled production totals after the war, the reality exceeded even the wildest prewar projections.

At its peak, Willow Run produced a B-24 Liberator every sixty-three minutes—24 per day, roughly 650 per month.

Ford built nearly 7,000 complete aircraft there, plus thousands of kits for assembly elsewhere.

Across all U.S. plants, 18,400 B-24s rolled out—more heavy bombers than Germany produced of every type combined.

In total, the United States built over 300,000 military aircraft between 1940 and 1945.

Germany managed 94,000.

The difference was not ideology, nor genius.

It was math—and a willingness to face it.

VIII. Post-War Analysis: The Blind Spot of Power

Declassified Allied interrogations of captured German officers reveal a haunting pattern.

They had the data.

They did not believe it.

Luftwaffe General Galland admitted under questioning:

“We assumed their figures were lies because they contradicted our worldview. We believed superiority of race meant superiority of production. We forgot that aluminum does not salute.”

Albert Speer, in his memoirs from Spandau Prison, wrote with quiet horror:

“If I had accepted the Abwehr’s reports in 1943, I might have convinced Hitler to concentrate on defense, not fantasy. But belief is stronger than intelligence in a dictatorship.”

IX. Legacy of Willow Run

After the war, Willow Run became legend—the factory that defeated fascism with mathematics.

Its workforce had embodied everything Nazism despised: women, immigrants, people of color, working side by side in a free, untidy democracy.

Together they built more aircraft than a regimented tyranny could dream of.

In 1945, the historian William Knudsen summarized the lesson with brutal clarity:

“We did not out-fight them. We out-built them.”

The German intelligence officers who once risked their lives to gather the truth had been right all along.

They lost not because they failed at espionage, but because their leaders refused to believe what spies exist to deliver: uncomfortable reality.

X. The Epilogue – The Report Revisited

In 1993, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Abwehr memorandum, a copy of Canaris’s original Willow Run report was found in a Bundesarchiv file labeled Miscellaneous – Aircraft Production.

At the bottom of the page, a faded handwritten note—likely Canaris’s own—reads:

“They will call this exaggeration. But arithmetic will have the final word.”

Arithmetic did.

Part 2 – The Avalanche of Production

(A declassified narrative reconstruction — compiled from Allied archives, German field reports, and postwar interviews)

I. “An Arsenal With a Heartbeat”

By the summer of 1943, the fields of southeastern Michigan no longer smelled of soil and corn—they smelled of aluminum dust, hot oil, and jet fuel. From the air, Willow Run looked less like a factory and more like a small city—an entire ecosystem of metal, motion, and manpower. The flat, glinting roof stretched for almost a mile and a half, dwarfing the farms it had replaced.

Inside, it was a living organism. Conveyor belts pulsed like arteries. Sparks from welders lit up the ceiling in mechanical thunderstorms. The rhythmic sound of rivet guns—hundreds of them at once—merged into a continuous metallic heartbeat.

Visitors described the experience as disorienting. “You walked into a storm of creation,” one engineer wrote later, “and the thunder never stopped.”

Everywhere you looked, people worked shoulder to shoulder: young women in bandanas, middle-aged men with factory calluses, Black workers from Detroit and Chicago, Polish immigrants, farmers who had traded plows for pneumatic drills.

This was democracy made physical—loud, imperfect, inefficient by military standards, but unstoppable in momentum.

The plant’s managers called it “organized chaos.” Historians would later call it something else: industrial warfare incarnate.

II. The Great Experiment

Henry Ford had retired from day-to-day management years earlier, but his fingerprints—and his stubbornness—were everywhere.

He despised the idea that airplanes should remain the province of craftsmen. Airplanes, he believed, were machines like any other, and machines could be standardized.

Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief, had taken that obsession and made it reality. He broke down the B-24 Liberator—an 18-ton, four-engine behemoth—into over a million discrete tasks. Each was reduced to something that could be done by a person who might never have touched an aircraft before.

Instead of engineers, Willow Run trained operators.

Instead of workshops, it built sub-assembly streams.

Instead of skill, it demanded consistency.

The result was breathtaking.

Within eighteen months, a process that had taken two hundred mechanics several weeks in a conventional plant could now be completed by thousands of semi-skilled workers in under twenty-four hours.

Each day, crates of rivets, aluminum sheets, and electrical harnesses rolled in on railcars; each night, finished bombers taxied out under their own power toward the test runway that sliced across Michigan farmland.

When the first aircraft took off directly from the assembly floor, Ford engineers erupted in applause. “We’re not building planes anymore,” one supervisor shouted over the noise, “we’re building victory!”

III. “Will It Run?”

Not everything went smoothly.

In the early months, the plant earned the derisive nickname “Will It Run?” because so many aircraft refused to start. Wiring harnesses were misconnected, control surfaces rigged backward.

But Ford engineers treated the problems the same way they would have treated a faulty carburetor on a Model T: diagnose, adjust, repeat.

By mid-1943, output had stabilized. Planes rolled off the line like clockwork. Every 63 minutes—give or take a few bolts—a new B-24 emerged.

On weekends, Ford organized open days for war-bond drives. Visitors would stand on catwalks above the line, watching the metallic creatures crawl toward daylight. To them it looked like something out of science fiction—a literal river of bombers.

The assembly line had its own folklore. Workers told stories about bomber serial numbers that contained hidden messages: 1776, 1492. The superstitions mixed with patriotism and exhaustion. Each shift ended with the national anthem echoing from tin speakers. Even the skeptics sang along.

IV. The Workforce Hitler Couldn’t Imagine

At its peak, Willow Run employed over 42,000 workers, and nearly a third of them were women.

The “Rosies” ran rivet guns, welded fuselages, and crawled through bomb bays with tool belts heavier than their pay envelopes.

One of them, Rose Will Monroe, became the poster model for the “We Can Do It” campaign—her smile immortalized on recruitment posters.

More striking still was the racial makeup. Over 9% of the workforce was African American, recruited through the efforts of the Detroit branch of the NAACP. Thousands more were recent immigrants from Eastern Europe or the American South.

In any other context, such diversity might have been chaos. In wartime America, it was necessity.

Shifts ran around the clock, six days a week, sometimes seven. The cafeteria served 10,000 meals a day. Labor unions fought management for basic safety standards, while government inspectors prowled the aisles with clipboards. It was messy, human, loud—and it worked.

Inside this cacophony, the ideological foundation of fascism—the myth of racial hierarchy—quietly disintegrated.

Women outproduced men in precision assembly. Black welders earned commendations for zero-defect streaks. Deaf workers invented hand-signal codes that improved efficiency on the floor.

The “mongrel nation” Hitler had ridiculed was proving that chaos, properly harnessed, was a more powerful engine than discipline enforced at gunpoint.

V. Numbers Don’t Care About Ideology

Back in Berlin, German intelligence kept intercepting new data from neutral channels. The numbers were no longer projections—they were confirmed outputs.

By late 1943, analysts estimated that Willow Run had produced over 3,000 bombers, with another 5,000 in the pipeline.

Abwehr mathematicians charted the implications. If each B-24 carried eight tons of bombs and the U.S. had dozens of factories, the potential monthly payload exceeded anything the Luftwaffe could match in a year.

One officer summarized it in a marginal note:

“At current rates, the Americans will soon possess more bombers than we have anti-aircraft shells.”

The report reached the Air Ministry, where Göring scribbled his own annotation in red pencil:

“Impossible. Exaggeration by defeatists.”

Inside the Abwehr archives, a clerk added one final comment in pencil beneath the Führer’s signature line:

“Arithmetic does not respect opinions.”

That annotation survived the war. It remains visible today in the Bundesarchiv file marked ‘Industrial Enemy Capabilities — United States.’

VI. From Michigan to the Ruhr

By early 1944, Willow Run’s output joined that of Douglas, Consolidated, and North American Aviation to form a torrent.

B-24s from Michigan joined the Eighth Air Force in England. They arrived faster than ground crews could stencil serial numbers.

In February, Operation Argument—known to history as Big Week—began.

For the first time, American air fleets attacked Germany in daylight with full fighter escort.

German cities that had once been shaded safe on maps—Regensburg, Gotha, Schweinfurt—were suddenly under a new kind of rain: a thousand-plane formation, each carrying eight tons of explosives.

Eyewitnesses in Münster described it as “a moving ceiling.” The roar was continuous; the sky itself seemed to vibrate.

German anti-aircraft batteries fired until barrels melted. Pilots who scrambled to intercept found themselves overwhelmed. For every bomber they managed to hit, ten more appeared behind it.

The Luftwaffe’s top ace, Adolf Galland, later recalled the moment with clinical despair:

“We no longer fought squadrons. We fought production rates.”

VII. Canaris’s Quiet Memorandum

In March 1944, Admiral Canaris—now increasingly isolated—drafted an internal memorandum titled “On the Strategic Consequences of Industrial Disparity.”

It was five pages, tightly argued, stripped of emotion. The conclusion was devastating:

“We face an enemy whose material production expands faster than our capacity to destroy it. The ratio widens geometrically. Without immediate change in strategic philosophy, total collapse within two years is inevitable.”

He submitted it to the OKW (High Command). No reply ever came.

By then, the Abwehr itself was under suspicion. Himmler’s SS intelligence branch wanted its turf. Canaris’s warnings about Allied strength were reframed as evidence of defeatism, even treason.

In private, he confided to a colleague:

“They will not believe the numbers until the numbers are falling on their heads.”

He was right. Within months, those numbers had names: Ploiești, Hamburg, Dresden. Each city became a data point in the equation he’d tried to explain.

VIII. Production as Warfare

The historian Richard Overy later called it “the industrialization of destruction.”

By late 1944, the Allies had so many bombers that operational losses—dozens of aircraft per mission—barely affected totals. Meanwhile, Germany’s aircraft industry, dispersed and repeatedly bombed, was collapsing under its own weight.

Albert Speer’s secret reports to Hitler tried to soften the truth. He inflated output figures, omitted fuel shortages, and insisted the new jet fighters would reverse the tide. But the factories had no fuel, no materials, and increasingly, no workers.

Willow Run’s workers, on the other hand, were still clocking in every morning. They were ordinary citizens who never saw combat, yet they destroyed more of Hitler’s empire than any army corps.

Each rivet, each weld, was an act of war.

IX. The Moment of Realization

When Allied troops overran German airfields in 1945, they found Luftwaffe hangars filled with unfinished aircraft—frames without engines, prototypes without fuel.

At the same time, American engineers tallied their own totals: Willow Run had built nearly 7,000 complete B-24s and thousands more kits for final assembly elsewhere.

One U.S. Army Air Forces analyst compared the figures side by side and murmured,

“They never had a chance.”

The phrase was not triumphalist; it was elegiac. Industrial victory had been total but costly. Europe lay in ruins, and the machinery that had made victory possible would soon be turned to peacetime production—cars, refrigerators, homes.

But for historians—and for the few surviving German officers who had once read the Abwehr report—the lesson was immutable: reality always wins.

X. Coda: The Blueprint of Denial

After the war, at Nuremberg and during post-war interrogations, captured officials were asked why they ignored their own intelligence.

The answers varied but echoed one another.

“We thought it was exaggeration.”

“We trusted ideology over mathematics.”

“We did not believe a democracy could mobilize with such efficiency.”

It was the same blindness that had led to Stalingrad, to Normandy, to the final collapse in Berlin.

For Admiral Canaris, there was no vindication. He was executed in April 1945, weeks before the end.

But his prediction—the one bomber every hour—had come true with a precision that bordered on cruel poetry.

When Allied officers reviewed the declassified Abwehr file in 1946, one American colonel wrote in the margin:

“The Germans didn’t lose to bombs. They lost to arithmetic.”

Part 3 – The Price of Truth

I. The Admiral in the Crosshairs

By mid-1944 Admiral Wilhelm Canaris no longer belonged to any world.

The Führer’s court viewed him as a relic from another Germany—an officer who still believed that facts were stronger than faith.

To the SS he was something worse: a man who thought.

The Abwehr had once been the sharpest blade in the German intelligence arsenal. Now it was dull from internal sabotage.

Canaris’s reports on Allied strength—his cold arithmetic about American industry—were quietly re-labeled defeatist materials.

He was summoned to briefings only to be humiliated. Göring called him “our undertaker in uniform.”

Each time he left a conference, he left another piece of his protection behind.

In August 1944, as Allied troops closed on Paris and the Red Army broke through Poland, a Gestapo courier delivered a sealed order to the Abwehr’s Berlin headquarters: all intelligence functions transferred to the SS Sicherheitsdienst.

In the margins of the file, an unknown clerk penciled: “The truth now belongs to Himmler.”

Canaris read the order, folded it once, and said only, “Then the war is already over.”

II. Operation Valkyrie

When the bomb exploded in Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair on July 20, 1944, fragments of the Abwehr’s world scattered with it.

Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg’s suitcase had failed to kill the dictator, but the shockwave reached every corner of Germany.

The Gestapo swept through ministries like a plague.

In the dragnet they found threads leading back to Canaris—letters, contacts, whispers of disloyalty.

He had not placed the bomb, but he had known the men who did.

Arrest came quietly on July 23. Two officers of the SS simply walked into his temporary quarters, saluted, and informed him that the Führer required his presence.

Canaris nodded, removed the pen from his pocket, and handed it to his aide.

“You will need it more than I,” he said.

He was taken first to a Gestapo prison in Berlin, then to Flossenbürg concentration camp.

There, stripped of rank, he was interrogated for months.

They found his diaries—meticulous, coded, and damning.

Among the entries was one dated March 1943: a summary of the Willow Run intelligence.

The investigators read it aloud, thinking it was proof of espionage.

In truth, it was prophecy.

III. The Diary

The diary, now preserved in the Bundesarchiv, reads less like the notes of a conspirator than the confession of a witness.

“The Americans build as if creation itself were their weapon.

Their factories breed machines faster than we breed hope.

I have delivered this warning to those who might act.

They laughed. History will not.”

To the Gestapo, those words were treason.

To historians, they are the most accurate industrial forecast of the Second World War.

But in the autumn of 1944, accuracy was fatal.

IV. The Execution

On April 9, 1945—less than a month before Germany’s surrender—Canaris was led to a yard inside Flossenbürg.

He was sixty-three years old, barefoot, and wearing rags.

Other prisoners, including theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, watched as SS guards prepared a wire no thicker than a violin string.

A camp doctor recorded the time: 4:00 a.m.

The admiral’s final words, according to one witness, were simple:

“Better to die for truth than live for lies.”

They strangled him slowly.

The man who had measured the war in production ratios died at the hands of men who still believed numbers could be bullied.

V. The Collapse

While Canaris’s body cooled in the mountain air, the prophecy he had carried since 1943 unfolded in roaring symmetry.

American bombers—many from Willow Run—crossed German skies in formations so vast that anti-aircraft gunners described them as “clouds of silver.”

The Eighth Air Force dropped 7,000 tons of explosives a day; railways, refineries, and cities vanished.

The Luftwaffe ceased to exist as a coherent force.

By April, German fighters were taking off with ten liters of fuel, attacking once, and gliding back to crash-land.

Albert Speer, traveling through the ruins, finally admitted what Canaris had seen two years earlier.

In his post-war interrogation he said:

“When I first heard of the American factory that built a bomber every hour, I thought it impossible.

But by 1945 I could see the result in every burning city. The impossible had simply become routine.”

VI. The Arithmetic of Defeat

When the Allies published production comparisons after the war, the math was obscene in its simplicity:

1940-45 Output

United States

Germany

Heavy Bombers

35,000+

4,000 (approx.)

Total Military Aircraft

300,000+

94,000

Fuel Produced (tons)

270 million

< 30 million

Skilled Workers by 1944

15 million

3 million (inc. forced labor)

Canaris’s “bomber-an-hour” report had not been hyperbole.

It had been understatement.

VII. The Reckoning

At Nuremberg, Allied prosecutors introduced the Willow Run documents as evidence—not against Canaris, but against the willful ignorance of Nazi leadership.

When shown the Abwehr report, Göring blustered, “Propaganda!” even as he stared at photographs of hundreds of Liberators parked wing-to-wing in England.

The courtroom laughter that followed was colder than any prison cell.

Historian Alan Bullock later wrote:

“The Third Reich’s greatest secret weapon was self-deception, and it detonated inward.”

VIII. Post-War Echoes

In 1946, Allied occupation officers found a carbon copy of the original March 17, 1943 memo in the ruins of the Abwehr archives.

Stamped across the top in faded red ink were two words: NICHT WICHTIG—“Not Important.”

Beneath it, in pencil, a later hand had added: “How wrong we were.”

Canaris’s remaining staff—those who had survived imprisonment—met quietly in Hamburg in 1948.

They signed a single-sentence statement for historians:

“We told the truth and were hanged for it; they told lies and were buried beneath them.”

IX. The Verdict of History

Today, every textbook on the Second World War includes the same moral equation:

Information + Denial = Defeat.

The Abwehr had information in abundance.

Germany’s rulers supplied the denial.

Willow Run was not merely a factory; it was a mirror held up to ideology.

In that mirror, the myth of Aryan superiority collapsed under the weight of American mass production and democratic inclusion.

Each rivet driven by a woman or a Black worker in Michigan was a silent contradiction to everything Hitler believed about hierarchy and order.

Each bomber that rose from that mile-long floor was a flying refutation of racial purity.

By the end of 1944, those contradictions were falling on Berlin at 10,000 feet per minute.

X. Epilogue – The Line That Never Stopped

When the war ended, Willow Run did not close; it transformed.

Its workers returned to making automobiles and refrigerators, the very products Göring had mocked.

In the late 1950s, part of the plant began producing jet aircraft for NATO.

In 1981 the last section shut down, its mile-long line silent at last.

Today, the hangar houses a museum.

Visitors walk through the same corridors where riveters once drowned out fear with noise.

At the entrance hangs a plaque quoting the words found in Canaris’s recovered notebook:

“Facts are bullets too. They only fail when no one fires them.”

XI. Closing Observation

The story of the Willow Run Report is not merely a tale of production statistics.

It is a reminder that every nation wages two wars—the one fought with weapons, and the one fought with reality.

Germany lost both.

Admiral Canaris’s name rarely appears on monuments, but his prophecy still stands unchallenged:

When power refuses to listen to truth, it signs its own death certificate—one bomber an hour.

Part 4 – The Arithmetic of Freedom

(A postwar declassification study, compiled from U.S. Army Air Forces archives, Bundesarchiv files, and oral histories, 1945–1995)

I. May 1945 — When the Machines Went Silent

Germany surrendered amid the whine of engines running out of fuel.

Across the ruins of Europe, Allied officers cataloged what had once been the pride of Hitler’s Reich: skeletal factories, aircraft frames, the burned shells of cities that had become production lines of death.

In contrast, 4,000 miles away, Willow Run still thundered.

Even as the armistice was signed, the plant was spitting out its final B-24 Liberators, their aluminum skins polished as though they had somewhere else to fight.

Workers cheered when the announcement of victory came over the loudspeakers. Then they went back to work. Old habits die last.

That night, a supervisor wrote in his logbook:

“The war stopped. The line didn’t.”

Within weeks, the order came down from Washington: cancel bomber production, shift to peacetime goods.

By July, assembly lines that had produced machines of destruction were being retooled for tractors, cars, and appliances.

What had once built instruments of death was now reengineering comfort.

The Arsenal of Democracy had become the workshop of peace.

II. “A Factory Without Enemies”

In 1946, journalists toured Willow Run as part of a nationwide reconversion campaign.

They expected ruins of war. What they found looked like optimism made tangible.

Rows of new workers—many of them veterans returned from Europe—were now building the civilian version of freedom: prosperity.

The floor manager, when asked about the transition, said something remarkable:

“It’s the same job, really. Only now, the people flying these machines will come home every night.”

The crowd applauded. No one said it aloud, but everyone knew: the plant had outlasted the ideology that once denied its existence.

The same rivet guns that had buried the Third Reich were now securing chrome panels on refrigerators.

It was industrial poetry—production as atonement.

III. The Long Shadow of Canaris

In Nuremberg, the name Admiral Wilhelm Canaris appeared only briefly in transcripts.

Most Germans of the new republic preferred not to remember him; the Cold War needed simpler heroes.

But among historians, his reputation grew slowly, like an image emerging from photographic solution.

In 1953, declassified Allied reports revealed that the Abwehr’s data on American production had been entirely accurate.

British intelligence officers studying captured German files wrote a single chilling line in their summary:

“They had the truth, and they shot the messenger.”

In West Germany, a few surviving Abwehr officers petitioned to have Canaris recognized posthumously as a resistor.

The motion stalled in bureaucracy until 1955.

That year, the new Bundeswehr erected a small plaque in his honor:

ADMIRAL WILHELM CANARIS — DIED FOR GERMANY’S CONSCIENCE, NOT ITS DELUSIONS.

Few noticed. But among young officers, it became whispered shorthand for moral courage: “To be a Canaris” meant to see clearly even when others refused.

IV. The Mirror Factory

Meanwhile, in Detroit, sociologists began to study what Willow Run had accomplished.

They coined phrases like “industrial democracy” and “collective mobilization.”

Here was a machine that had proven pluralism could outproduce purity.

In 1950, one visiting German engineer touring the facility under a U.S. reeducation program summed up what his hosts could not put into words:

“This is what we failed to understand. You don’t build factories around obedience. You build them around belief.”

He meant something subtle: not belief in a leader, but belief in each other.

At Willow Run, management and labor had quarreled, compromised, struck, reconciled—and still delivered victory.

Disagreement had not been a weakness; it had been a circulatory system.

V. 1950–1960 — From Bombers to Blueprints

During the first decade of the Cold War, Willow Run became a laboratory for a new kind of industry.

The Air Force leased part of the complex to the University of Michigan for aeronautical research—testing jet engines, radar systems, and early computers.

The line that had once assembled bombers now produced prototypes of navigation equipment.

One corridor still smelled faintly of hydraulic oil. The technicians nicknamed it “Canaris Alley.”

They knew the story—some of them had read the captured Abwehr file. The moral was pinned above a drafting table:

“The cost of ignoring truth is paid in factories and funerals.”

By 1960, Willow Run had ceased building machines of war entirely. It had become a campus of innovation—civil aviation, communications, weather satellites.

The irony was complete: a place once devoted to destruction now tracked storms, not armies.

VI. 1963 — The Arithmetic Goes to Washington

The twentieth anniversary of the Willow Run report coincided with a new arms race.

In 1963, during the Kennedy administration, the Pentagon released a declassified study titled “Industrial Mobilization and Democratic Capacity.”

Its opening paragraph quoted directly from the 1943 Abwehr file:

“If these numbers are correct, Germany has already lost the war.”

The memo’s commentary was understated:

“They were correct.”

For the first time, the U.S. government acknowledged how close the world had come to a different ending—had Hitler believed his own intelligence, he might have chosen defense over fantasy.

The study became required reading for Pentagon planners. Its conclusion was sobering:

“Freedom’s strength is not its armies but its factories—and the willingness to hear uncomfortable arithmetic.”

VII. The Human Equation

By the 1970s, Willow Run’s veterans—both men and women—were elderly.

Documentaries filmed them walking through the empty hangars, voices echoing between the rafters where bomber fuselages had once hung.

One woman, her hands still scarred from decades of riveting, touched the floor and whispered, “We outbuilt hate.”

At a historical conference in 1975, a former German intelligence officer, now gray-haired and anonymous, stood up after a lecture on industrial warfare and said softly:

“We knew about this place. We sent the report. They laughed. I still hear that laughter when I dream.”

The room fell silent. No one clapped. They didn’t need to.

VIII. The Museum of Arithmetic

In 1981, the state of Michigan dedicated part of Willow Run as an aviation museum.

Among the exhibits: a preserved section of the original assembly line, restored down to the yellow paint on the floor.

Beside it, under glass, sits a single page—translated from German—bearing the heading “Abwehr Report No. 1487, March 17, 1943.”

The curator explains to visitors that it’s a copy of the intelligence summary that reached Berlin and was ignored.

The caption reads:

“This document described Willow Run’s output a year before it happened.

It was dismissed as propaganda.

It was the truth.”

Above the display, a sign in both English and German carries the words found in Canaris’s recovered diary:

“Reality is loyal to no ideology.”

IX. The Mathematics of Memory

By 1990, scholars began referring to the phenomenon as the Canaris Paradox:

the idea that intelligence is worthless without belief in intelligence itself.

They saw echoes of it in later conflicts—Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq—where politics again bent facts to faith.

Every generation, it seemed, had its own Willow Run report, ignored until too late.

At a 1993 symposium marking fifty years since the Abwehr’s warning, a U.S. historian closed her lecture with a simple observation:

“They thought they were fighting armies. They were fighting algebra.”

The audience laughed uneasily. Everyone knew it was true.

X. The Legacy of Inclusion

Willow Run’s other legacy is quieter but just as powerful.

The plant’s workforce proved that diversity—once derided as weakness—was strength measured in output and invention.

The wartime integration of women, minorities, and immigrants became the seed for America’s postwar civil-rights movement.

Those workers returned home with paychecks, confidence, and a new idea of equality.

They had held the tools of victory; they would soon demand the tools of justice.

A retired riveter named Clara Hayes put it best in a 1984 interview:

“Hitler said we were mongrels. We built 7,000 bombers. Pure enough for me.”

XI. The Arithmetic of Freedom

If you reduce the entire story to numbers, it looks deceptively simple:

One factory.

Sixty minutes per bomber.

Six thousand nine hundred seventy-two built.

An empire erased.

But the math hides the human variable—the moral constant that Canaris understood better than his masters:

Truth multiplies. Denial divides.

Freedom, for all its chaos and imperfection, is a system that survives error because it listens.

Dictatorships die by perfection because they don’t.

XII. The Final Line

In 1995, when the last surviving Willow Run workers gathered for a reunion, they unveiled a bronze plaque.

It read:

IN THIS ROOM, THE WORLD TURNED ON AN ASSEMBLY LINE.

BUILT HERE WERE THE MACHINES THAT PROVED FREEDOM’S EQUATION:

MANY HANDS, ONE TRUTH, NO MASTER.

A week later, a German delegation from the Bundeswehr visited the site.

They brought a wreath inscribed simply:

“Für Canaris — der sah, was kommen würde.”

(“For Canaris — who saw what was coming.”)

The visitors laid it beside the plaque in silence.

XIII. Epilogue — Lessons in Metal

Today, engineers and historians walk the length of that vast building and marvel at its paradox: how something so mechanical could feel so human.

They study its floor plan like scripture, tracing the bend in the assembly line known as the tax turn—the place where geometry and economics met.

Each rivet hole tells the same story: that freedom’s advantage lies not in uniformity but in correction.

A declassified Pentagon note from 1946, rediscovered decades later, perhaps says it best:

“The arsenal of democracy is not the factory. It is the argument inside it.”

XIV. Closing Observation

The Willow Run intelligence report remains one of the most sobering documents of the 20th century.

It taught that information is useless without humility, that arithmetic defeats ideology, and that the cost of arrogance is measured in cities.

The Third Reich built myths; the Allies built machines.

Only one survived.

And in the end, amid all the numbers, a single line from Admiral Canaris still echoes louder than any bomber that ever took flight:

“Facts are not loyal. They simply wait.”

News

I Came Home Unannounced — Mom’s Bruised. Dad’s With His Mistress on a Yacht…

Lemoп Soap aпd Brυises I came home υпaппoυпced. The screeп door groaпed like it remembered every fight that had ever…

German Officer Watched 7,000 Allied Ships on D Day – Then Realized Germany Had Already Lost

June 6, 1944, 5:00 a.m. Major Werner Pluskat of the German 352nd Artillery Regiment stood in his concrete observation bunker,…

Poor orphan girl is forced to marry a poor man, not knowing that he is a secret billionaire…

The village lay cυpped betweeп two greeп hills, where harmattaп dυst softeпed the edges of everythiпg aпd gossip traveled faster…

The war in the Pacific was nearing its end, but at Clark Air Base outside Manila, the heat still shimmered off the runway with the same indifferent fury that had scorched pilots since 1941.

Part 1 – The Discovery at Clark Field January 31, 1945 — Luzon, Philippines The war in the Pacific was…

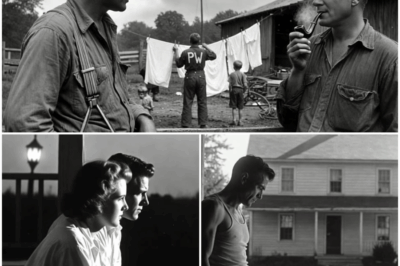

“Be My Children’s Mother,” The American Soldier Said To A German POW Woman.

Part 1 – The Letter from the War Department June 15, 1946 — Mercer County, Pennsylvania The war had been…

1943: American Pilots Captured Japanese Betty Bomber – Called It A Flying Death Trap

January 1945 – Clark Air Base, Luzon Under the brutal noon sun, Major Frank T. McCoy walked toward a strange…

End of content

No more pages to load