Part 1 – The Discovery at Clark Field

January 31, 1945 — Luzon, Philippines

The war in the Pacific was nearing its end, but at Clark Air Base outside Manila, the heat still shimmered off the runway with the same indifferent fury that had scorched pilots since 1941.

Major Frank T. McCoy, U.S. Army Air Forces, stepped out of a Willys jeep and shaded his eyes against the glare.

He had come to examine what intelligence officers called a “Category A capture” — a complete, flyable example of a Japanese bomber abandoned during the enemy’s hasty retreat.

McCoy was thirty-four and already carried the weariness of a man who had spent three years picking through the wreckage of the Pacific war.

From the coral atolls of the Solomons to the jungles of New Guinea, he had crawled through twisted fuselages, taken measurements, and filed reports that turned burned aluminum into data points.

He had studied the Zero, the Oscar, the Sally, the Nick.

He thought he had seen everything the Japanese could build.

He was wrong.

Before him on the tarmac sat a Mitsubishi G4M “Betty”, tail number 763-12, its paint faded, its glass blistered but intact.

Unlike the usual carcasses dragged from crash sites, this aircraft appeared almost new.

Even the Rising Sun insignia on the tail was still visible beneath the grime.

It had been captured intact near Lingayen Gulf, its crew apparently abandoning it when the retreat turned into chaos.

Mechanics had ferried it south on flatbed trucks, repaired minor damage, and parked it on the apron like a specimen awaiting autopsy.

McCoy climbed onto the port wing, the metal hot enough to burn through the knees of his khakis.

He located the first inspection panel and released the latch.

The hinge creaked, revealing a polished cavity that made him stop cold.

Inside, under the tropical glare, the bomber’s fuel tanks gleamed like bare tin.

No rubberized coating. No armor. No fire-suppression plumbing.

Just a thin 2-millimeter layer of aluminum separating thousands of liters of high-octane gasoline from the outside world.

He opened another panel.

Then another.

The same: naked tanks, unprotected, exposed.

It was not battle damage. It was design.

“Jesus Christ,” he muttered. “This thing’s a flying cigarette.”

The Japanese had built an aircraft that valued distance over survival — an engineering choice that suddenly explained years of combat reports describing Betty bombers erupting into flame with a single .50-caliber burst.

Here, in the tropical sunlight, McCoy was staring at the reason.

Tokyo, 1937 — The Impossible Specification

Back in Washington, the captured documents would later confirm the story’s beginning.

In 1937, the Imperial Japanese Navy Bureau of Aeronautics had issued an extraordinary requirement to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries:

A land-based attack bomber capable of carrying an 800-kilogram bomb load across 2,400 kilometers at 400 kilometers per hour. Crew: seven.

No aircraft in the world could meet all three numbers.

American bombers such as the B-17 prioritized defensive guns and armor.

The British sought payload capacity.

The Japanese demanded reach — a bomber that could strike anywhere in the Pacific from home islands or forward bases, without refueling.

Chief designer Kiro Honjō confronted the arithmetic immediately.

Fuel was weight, and weight was the enemy of range.

To meet the specification, the G4M would need almost 4,800 liters of gasoline — over 3,400 kilograms of mass before the first bullet or bomb was loaded.

Something had to give.

In the West, engineers solved this by adding self-sealing fuel tanks — rubber-laminated layers that swelled when pierced, choking off leaks and saving lives.

Honjō calculated that such a system would add at least 500 kilograms.

That half-ton would cut the aircraft’s operational radius by nearly 1,000 kilometers — unacceptable to the admirals who viewed the Pacific not as a battlefield but as an ocean to be crossed.

So Honjō made the fateful choice: eliminate protection entirely.

Every saved kilogram became range.

Every ounce of safety was traded for distance.

1939 – 1941 — Triumph Before Tragedy

The prototype first flew in October 1939.

The numbers were astounding: a top speed of 428 kilometers per hour and an unarmed range exceeding 6,000 kilometers.

When the Navy tested it, officers applauded.

No other bomber on earth could travel so far, so fast, with such a modest crew.

By April 1941, the first G4M Model 11s reached operational units.

Pilots nicknamed it Hamaki — “The Cigar” — for its long fuselage.

The aircraft could strike anywhere from Formosa to Singapore to the Philippines.

To admirals planning a vast maritime empire, it seemed a wonder of modern engineering.

Veteran aircrews, however, noticed what was missing.

There was no armor behind the pilot’s seat, no plating beneath the floor, and—most ominously—no protection around the fuel cells.

They exchanged knowing glances but kept silent.

In the Japanese Navy Air Service, questioning a specification was not professional—it was insubordination.

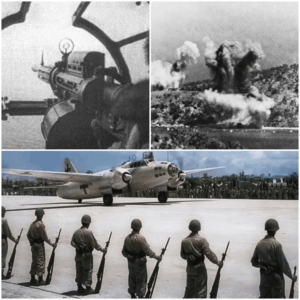

December 1941 — The Opening Blows

At dawn on December 8 (local date, still December 7 in Hawaii), 82 G4Ms and 26 G3Ms lifted off from Formosa.

Their target: Clark Field, the principal American base in the Philippines.

Flying 460 miles to the south, they arrived shortly after noon.

Within forty-five minutes, they reduced the airfield to ruin—seventeen B-17s on the ground, twelve destroyed, the rest crippled.

Most American fighters never got off the runway.

The Bettys returned to Formosa untouched.

They had struck from a distance beyond the reach of any Allied aircraft in Asia.

The admirals were ecstatic.

Two days later, the G4Ms achieved an even more astonishing success.

On December 10, twenty-six Bettys from the 22nd Air Flotilla located British Force Z — the battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse — off the coast of Malaya.

Coordinated torpedo runs sent both warships to the bottom within two hours.

It was the first time in naval history that fully active capital ships had been sunk solely by aircraft.

Winston Churchill later called it “the most grievous blow ever struck at British sea power.”

To Japan, it was vindication.

The Betty was unstoppable.

1942 — The Edge of the World

Through the first half of 1942, the G4M seemed omnipresent.

From Rabaul to the Dutch East Indies, they struck Allied positions far beyond expected range.

On February 19, 1942, twenty-seven Bettys participated in the raid on Darwin, Australia, flying 1,500 miles round-trip.

In the jungles of New Guinea, they bombed Port Moresby almost daily, traversing mountain ranges that grounded lesser aircraft.

For a time, the Allies could do nothing.

Rabaul lay beyond the reach of their fighters.

The Betty’s range gave Japan a form of tactical omnipotence—an ability to hit anywhere, anytime.

But advantage built on fragility cannot last.

The moment the Allies closed the distance, the equation would reverse.

August 1942 — The Guadalcanal Massacre

That reversal came on August 8, 1942.

Twenty-three G4Ms from the 4th Air Group departed Rabaul on what was supposed to be a routine mission against the newly captured American airfield on Guadalcanal.

They expected another unopposed run.

Instead, Marine F4F Wildcats from Henderson Field intercepted them at 10,000 feet over the island of Savo.

Captain Marion Carl led the attack.

“We came at them from high and ahead,” he later recalled. “The moment our rounds hit their wings, they just exploded. I’d never seen anything like it.”

Eighteen of the twenty-three bombers went down in flames within minutes.

Five limped home, jettisoning their bombs to lighten the load.

A hundred and twenty men died in that single engagement.

From that day forward, Allied pilots learned to aim for the wings.

A few .50-caliber hits anywhere near the root ignited the entire fuel system.

Japanese crews began calling their own aircraft Hamaki with gallows humor.

American pilots coined their own nicknames: “Flying Cigar.” “Flying Zippo.”

Ensign James Swett, who shot down seven Japanese aircraft in one mission, summed it up succinctly:

“Hit the wing and it’s over. The whole thing lights up like a torch.”

What had been Japan’s long-range sword became its funeral pyre.

1943 — The Engineers’ Confirmation

The U.S. confirmation came months later when Allied forces overran Japanese positions at Buna, New Guinea, and found nearly intact wrecks.

Technical Sergeant Robert Hayes pried open a wing panel and saw what McCoy would later find at Clark: thin metal, open fuel cells, no protection.

Western engineers shook their heads in disbelief.

The absence of self-sealing tanks was not an oversight; it was policy.

American bombers like the B-17 and B-24 routinely added half a ton of protection for each crew.

Japanese designers had chosen the opposite path.

The numbers told the story:

A B-17’s empty weight was 16,000 kilograms — more than double the Betty’s 6,700.

But that extra mass translated into a survivability rate of nearly 97 percent per mission in the Pacific.

The Betty’s was barely 85 percent, and dropping fast.

By mid-1943, the average G4M crewman’s chance of surviving thirty missions was under one in three.

Letters from the Cockpit

Japanese diaries and letters captured after the war revealed the human cost behind the arithmetic.

Lieutenant Fujiya Yū, pilot with the Takao Air Group, wrote home in October 1942:

“We call our aircraft Hamaki. Every mission, we joke about who will light up today, but it isn’t really a joke. Yesterday Tanaka’s plane took one hit on the bomb run. We saw the fire from two kilometers away.”

Another gunner, Petty Officer Kawasaki Hiroshi, recorded in his notebook:

“Third mission to Guadalcanal. Fourteen aircraft departed. Nine returned. We are not flying bombers anymore—we are flying coffins that happen to have wings.”

The Ignored Warnings

Senior officers knew. Reports circulated as early as late 1942 warning that the G4M’s vulnerability was unsustainable.

Lieutenant Commander Takahashi Kauichi’s memo to Navy Headquarters was explicit:

“The G4M is operationally obsolete. Every mission ends in death. Either we build a protected aircraft or we cease these operations.”

No redesign came.

Japan’s industrial capacity was already collapsing under the strain of blockade and bombardment.

The choice was to keep flying the existing model—or fly nothing at all.

And so, crews kept climbing into the same fragile machines, each flight a gamble between obedience and annihilation.

1943 — The Death of Yamamoto

The most symbolic loss came on April 18, 1943.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of Pearl Harbor, was traveling from Rabaul to Bougainville in a G4M.

American cryptanalysts, having broken the Japanese naval code, dispatched P-38 Lightnings to intercept.

Lieutenant Rex Barber described the moment:

“We came in from below and behind. I fired a burst into the wing root. The bomber caught fire instantly. The whole wing was burning before I could pull away.”

Yamamoto’s aircraft crashed into the jungle. No one survived.

The same unprotected fuel tanks that had given the Betty its reach had now consumed the man who had demanded it.

Part 2 – The Anatomy of Sacrifice

Clark Air Base — February 1, 1945

Major Frank T. McCoy’s field notebook opens with one terse sentence written in pencil on damp paper:

“Range purchased at the cost of human life.”

For the next three days he and two engineering officers from the Fifth Air Force Technical Intelligence Section dismantled tail number 763-12 under the merciless Luzon sun. They photographed every panel, traced every fuel line, measured armor thickness that in many places was literally zero. Each note told the same story—the Betty’s greatness and its doom were the same feature.

When McCoy finally filed his report, it ran forty-three pages, classified Secret – Technical Evaluation, Mitsubishi G4M Type 1 Attack Bomber. The language was clinical but the verdict read like an epitaph.

Excerpt – McCoy Report, Section IV: Fuel System

“Primary fuel storage: four wing tanks and two fuselage tanks of Alclad aluminum, 2 mm average thickness. No internal baffles, no inert-gas purging, no self-sealing coating. Vulnerable area approximates 32 square meters. One incendiary tracer round entering at any point will likely result in catastrophic fire.”

“This design provides remarkable weight economy—approximately 500 kg saved compared to American self-sealing systems—but offers no survivability margin.”

“Conclusion: deliberate omission, not oversight.”

McCoy added a marginal note in his own handwriting:

“They built a range champion and condemned seven men each flight.”

Engineering Context — The Mathematics of Range

A bomber’s endurance is an equation:

Fuel Weight ÷ Drag × Engine Efficiency = Distance.

The G4M’s twin Mitsubishi Kasei 14-cylinder engines were reliable, but their power-to-weight ratio was already near limit. To reach the Navy’s demanded 2,400-kilometer radius, every extra liter of fuel required subtraction somewhere else—armor, ammunition, structure. Japanese design culture, steeped in the bushido ideal, favored performance and audacity over prudence. Survival, they reasoned, was subordinate to mission success.

The result was a bomber that could fly farther than any in its class—and die faster than any in history.

The Guadalcanal Data Curve

Intelligence summaries from late 1942 charted the new reality. In August the G4M loss rate was 78 percent per mission; by October, 64 percent; by December, 55 percent. Statisticians in Honolulu noticed an eerie consistency: regardless of mission size, roughly two-thirds never returned. By American standards that was annihilation; by Japanese logic it was acceptance.

Captured diaries confirmed that crews knew the odds. They joked grimly about drawing the short match before take-off. They called their aircraft Hamaki—the Cigar—and sometimes Hi no tama, “ball of fire.” No slang could disguise that every sortie was a calculated suicide not called by that name.

The Ignored Solutions

By early 1943, technicians at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal had proposed adding laminated rubber bladders inside the wing tanks—an adaptation of Allied self-sealing technology observed from captured aircraft in Malaya. The modification added 480 kilograms and reduced range by 900 kilometers. The proposal reached the Naval Air Staff in March. Admiral Kusaka’s handwritten comment in the margin settled the matter:

“Losses acceptable. Range indispensable.”

The memorandum was stamped Rejected – Operational Requirements. No further discussion occurred.

The Attrition Paradox

A declassified postwar U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey would later define what McCoy saw in that cockpit as “the attrition paradox.” Japan’s emphasis on range allowed it to strike first and broadly—but every raid that reached its target cost it the very crews needed to fight the next one. Between 1942 and 1944 the Navy lost over 10,000 aircrew, most of them trained specialists who could not be replaced. Each month the average flight hours of replacement pilots dropped; each month the burn rate increased. By the summer of 1944, surviving veterans joked bitterly that the real Japanese secret weapon was experience wasted faster than built.

Case Study — Operation I-Go, April 1943

Yamamoto’s last offensive used ninety-eight G4Ms. Thirty-six failed to return. Those numbers reached McCoy through intercepted radio decrypts and would reappear in his appendix.

He underlined them twice and added:

“This is not strategy. This is arithmetic with corpses.”

Human Documents

Among the papers found inside 763-12’s radio compartment was a small notebook, waterproofed with oilcloth. Written in katakana and halting English phrases, it belonged to a crew chief named Sasaki Koji. Translation, filed with McCoy’s report, reads:

March 2 1944 – Night raid on Hollandia. Saw 3 planes burn before bomb release. Fuel fumes strong in cabin; we smell death even before combat. Still, we must go. The sea waits below like a mirror for our fire.

McCoy read it twice, then dictated to his stenographer:

“Include excerpt. Technical evaluation cannot exclude moral dimension.”

That sentence would start a quiet argument inside the intelligence community: should morality appear in a technical document? McCoy insisted it must.

April 1943 — The Lesson Ignored

The downing of Admiral Yamamoto should have changed everything. Instead, it became another martyrdom. When intercepted P-38s shredded his G4M, the Japanese press did not mention the aircraft’s vulnerability; it praised the Admiral’s courage. To Western engineers the message was clear: ideology had replaced physics.

Even so, McCoy noted a grim symmetry. The same unprotected tanks that had carried Yamamoto’s victories at Pearl Harbor carried his defeat through the jungle canopy of Bougainville. He wrote in his diary:

“The design that served their ambition also served their extinction.”

The Final Model — G4M2

By 1944 Mitsubishi released an updated variant with slightly thicker wing skins and extra 7.7 mm gun mounts. The improvements added 400 kg but no real protection. Self-sealing tanks were still omitted. The manufacturer’s brochure claimed the new model could sustain “limited battle damage.” Captured pilots later laughed bitterly at the phrase. “Limited battle damage,” one said, “means you are still talking while burning.”

March 21 1945 — Operation Ohka

If the Betty’s story had begun with triumph at Clark Field, it ended in tragedy off Okinawa. Eighteen G4Ms departed Kyushu carrying Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka rocket bombs—manned gliders intended to dive into Allied ships. Each weighed 2,600 kg, slung under the bomber’s belly like a lead crucifix.

Radar picked them up sixty miles out. Hellcat fighters intercepted before release range. None survived. One American pilot later recalled:

“It was like shooting through floating gas cans. You didn’t even have to aim—just fire, and the whole sky caught fire.”

All eighteen aircraft disintegrated. 137 bomber crewmen and fifteen Ohka pilots perished. Not one American ship was hit.

In his after-action brief, Admiral Spruance remarked drily, “The enemy continues to mistake bravery for strategy.”

Comparative Analysis — The B-17 vs G4M

McCoy’s technical summary juxtaposed the Betty with America’s Flying Fortress.

Specification

Mitsubishi G4M Model 11

Boeing B-17G

Empty Weight

6,741 kg

16,391 kg

Max Range

3,000 mi

2,000 mi

Defensive Guns

5–7 × 7.7/20 mm

13 × .50 cal

Crew Survivability (per mission)

85% → 60% (1943)

97% (average)

McCoy concluded:

“The United States trades 1,000 miles of range for five times the survival rate. Japan trades five lives for 1,000 miles. In the long term, the former accumulates skill; the latter consumes it.”

The line was later quoted verbatim in the U.S. Army Air Forces Tactical Review, June 1946, under the heading Lessons of the Pacific.

Attrition as Doctrine

Japanese commanders attempted to compensate for aircraft fragility by elevating spiritual endurance—seishin—to the level of armor plating. Crews were lectured that devotion would deflect bullets. When that failed, they simply died obediently. By 1944, some squadrons flew with average pilot age under 20. Training time had dropped from 18 months to 6. Fuel shortages forced classroom lectures to replace flight hours. The Betty demanded experience; the empire supplied novices.

McCoy’s appendix charts the downward spiral: each wave less trained, each loss erasing another instructor. The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service was eating itself alive.

The Surrender Flight

On August 19 1945, two G4Ms painted white with green crosses lifted off from Atsugi Air Base. Their mission: carry the Japanese surrender delegation to Ie Shima to meet American envoys. The irony was absolute. The aircraft that had opened the Pacific war by destroying Clark Field now carried the men who would end it.

Photographs show the bombers taxiing past wreckage of their own making—burned Bettys littering the edges of the runway. American officers inspecting them later noted bullet holes crudely patched with tin, as though the war itself had been held together by sheet metal and faith.

McCoy, reviewing the images months later, wrote a single sentence beneath them:

“The final flight of the Betty was peace, because every other mission had been death.”

Post-War Evaluation — 1946

In April 1946, the U.S. Air Technical Intelligence Command compiled McCoy’s findings with British and Australian analyses into Report No. 43-A: Japanese Aviation Philosophy. Its conclusion distilled four years of carnage into one paragraph:

“Japanese aircraft design prioritized capability over survivability. The strategic consequence was irreversible loss of trained personnel. The nation that protected its crews grew stronger; the nation that sacrificed them collapsed from within.”

The report was later declassified and circulated among NATO allies as a cautionary study in “cultural engineering bias.” Its lessons echoed far beyond aviation.

The Aftermath — McCoy’s Reflection

When interviewed in 1953 for an oral-history project, McCoy summarized what he had seen that January day at Clark Field:

“They built a masterpiece that murdered its own crews. I remember running my hand along that wing and thinking, ‘this isn’t design, it’s confession.’ They confessed what they valued: reach, not return. We valued return, and that’s why we reached the end of the war still flying.”

He paused, then added with a sardonic smile:

“If there’s poetry in machinery, the Betty was a tragic poem—beautiful meter, fatal meaning.”

Moral Addendum — The Different Values of War

Technical intelligence officers were not philosophers, but even bureaucrats noticed the contrast. The American ideal: bring your men home, let veterans train the next generation. The Japanese ideal: complete the mission even if the mission consumes you. In steel and aluminum, those ideals took shape—self-sealing rubber versus bare tanks, armor plates versus prayer flags.

In the end, one philosophy produced an air force that improved with every sortie. The other produced smoke on the horizon.

Legacy – A Tomb of Aluminum

Today, fragments of the G4M still lie scattered across the Pacific—rusted ribs jutting from jungle soil, corroded spars resting in turquoise lagoons. Marine archaeologists call them “aluminum tombs.” Each once carried seven men whose lives were traded for an extra thousand miles of reach.

Clark Air Base itself would later host jets that crossed oceans in hours, powered by turbines whose designers studied McCoy’s report as gospel: protect the pilot, preserve the skill, win the long war.

Part 3 – Range, Faith, and Fire

Tokyo — The Cult of Range

By late 1943, Japanese war industry meetings were conducted in windowless rooms that smelled of sweat and kerosene. Engineers argued weight tables while naval officers quoted poetry about destiny. What began as engineering had become theology.

Minutes from a surviving Navy conference record Vice Admiral Kusaka saying:

“The Pacific is vast; whoever masters distance masters fate.”

That sentence became doctrine.

“Range,” in Imperial logic, was not just a number; it was a moral virtue. To reach farther meant to prove willpower. The engineers who suggested sacrificing radius for safety were quietly replaced. The phrase “to return alive is secondary” appeared in training manuals.

Thus the G4M—bare-metal tanks, paper-thin armor—was not an aberration.

It was a mirror of the nation that built it.

Faith as Armor

Japan’s wartime education system fed young aviators a mixture of physics and metaphysics. Instructors spoke of seishin ryoku—spiritual power—as a measurable force. At the Yokaren Naval Air School, cadets recited before flight:

“Our bodies are shells; our souls the bullets.”

When self-sealing rubber was suggested again in 1944, an admiral replied that “rubber is a foreign material; spirit is Japanese.” Logistics surrendered to ideology.

Pilots took off believing that courage could deflect a .50-caliber round.

The Americans, meanwhile, wrapped their courage in rubber and steel.

Material Reality

U.S. engineers knew the numbers by heart:

One pound of armor saved a life for every forty missions.

One self-sealing tank prevented, on average, three aircraft losses per hundred sorties.

Japan could not afford either.

Aluminum production had fallen by 60 percent since 1942. Rubber was imported from territories now under blockade. Synthetic substitutes cracked in heat. Even if the Navy had wanted protection, factories could not supply it.

So the moral choice—to sacrifice survivability—merged with the practical constraint: there was no material left to save anyone.

The American Contrast

At Wright Field, Ohio, U.S. Air Technical Service Command studied the Betty’s blueprints alongside the B-17 and B-24. Colonel Elmer Davison summarized the philosophical divide:

“They built for the first mission; we built for the fiftieth.”

Every American bomber crewman was an investment of training hours—up to 250 flight hours before deployment. Japan’s average by 1944 was 90. The United States could replace machines faster than men; Japan replaced men faster than machines.

McCoy’s report became a cautionary exhibit in lectures to new design engineers: “Beware the false economy of bravery.”

The Spiritual Engine

Captured Japanese diaries repeatedly used one phrase: “We will burn beautifully.”

The words horrified translators at Allied headquarters. Yet to the writers, it was sincere. The Betty’s shimmering aluminum fuselage, polished to reduce drag, became a metaphor for purity. Even its vulnerability was romanticized.

A surviving leaflet distributed to naval aviators in 1944 reads:

“Our aircraft are light because our hearts are light. Heavy armor belongs to nations that fear death. We, who do not, shall fly farther.”

Faith had become fuel.

McCoy’s Addendum — The Psychology of Design

In 1946 McCoy submitted an unsanctioned annex to his original technical report titled Psychological Factors in Japanese Aircraft Engineering. It was classified “For Internal Discussion Only.” In crisp bureaucratic prose he wrote:

“When a culture equates self-destruction with honor, its machines will reflect that equation. The G4M is not a mistake of mathematics; it is a confession in metal.”

He noted that every design choice—the thin skin, unarmored crew compartment, even the removal of bullet-proof glass in later models—aligned with a national readiness to die usefully rather than live inconveniently. “Aviation,” McCoy concluded, “was theology with propellers.”

Industrial Limits — The Numbers Collapse

By mid-1944 Japan’s aircraft industry resembled a patient on oxygen.

U.S. bombing of Nagoya and Osaka shredded assembly lines; Mitsubishi’s main plant operated at 30 percent capacity. Replacement bombers arrived without radios or navigation instruments. Some crews flew with wooden control surfaces lacquered to resemble aluminum.

Production records show only 117 G4Ms completed in the first quarter of 1945—less than one week’s output for American heavy bombers.

Fuel shortages forced test flights to taxi distances instead of airborne trials. Engineers wrote “performance satisfactory” after simply revving engines on the runway.

Range had ceased to matter; there was nowhere left to fly.

The Endgame Mindset

In those final months, the G4M became a vehicle not for bombs but for ideology. Converted into Ohka carriers, it transported suicide weapons to their launch point—a grim literalization of what it had always been. Surviving officers later admitted the logic was circular:

“We built a bomber that would die quickly, so we assigned it to missions where death was the objective.”

McCoy would underline that sentence in a translation margin years later and write: “Design finds its destiny.”

The Clark Field Findings — Revisited

After the war, investigators revisited McCoy’s captured Betty, still stored under tarpaulin at Clark Air Base. The airframe was weathered, but the fuel tanks remained bare aluminum, oxidized to dull gray. Engineers sliced one open with a power saw; the walls were thin as roofing sheet. When the saw teeth bit through, the tank crumpled inward like paper.

One observer remarked, “I’ve seen thicker canteens.”

Another whispered, “This is how 10,000 men died.”

The piece was shipped to Wright Field and displayed beside a self-sealing tank from a B-25. The contrast—one heavy, rubber-coated, resilient; the other light, fragile, tragic—became an exhibit in lectures on “Design Philosophy and National Psychology.”

Faith vs Feedback

Postwar Japanese engineers, interviewed during the U.S. occupation, admitted that pre-1945 design culture discouraged bad news. An engineer at Mitsubishi told investigators:

“If a prototype failed, we blamed ourselves, not the idea. If we questioned the idea, we disgraced our superiors. So we made it work on paper.”

That single sentence, McCoy later said, was worth a library of intelligence manuals. “They replaced testing with faith, feedback with reverence,” he wrote.

Doctrine Reversal — The Allied Lesson

McCoy’s conclusions spread quietly through American and British research centers. They influenced not only post-war bomber design but also early Cold War engineering ethics. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s new Aeronautics Laboratory, instructors told students:

“Never let ideology write your weight tables.”

The Air Force’s first jet bombers—the B-47 and B-52—carried McCoy’s fingerprints in their thick fuel-tank bladders and redundant systems. The obsession with crew survivability became a moral counterpoint to the Betty’s legacy.

Cultural Reckoning — Japan, 1950

Five years after the surrender, Japan’s new Self-Defense Forces commissioned a memorial study on wartime aviation. Engineers who had once served under Honjō read McCoy’s declassified analysis with a mixture of shame and relief.

One designer, interviewed by Asahi Shimbun, said quietly:

“We thought we were proving courage. We were only proving physics does not forgive belief.”

The G4M’s silhouette, once a symbol of reach, now represented futility. Its surviving blueprints were stored not in factories but in museums.

The Moral Equation

Analysts later summarized McCoy’s findings as an equation of values:

Value

American Design

Japanese Design

Objective

Endure

Sacrifice

Measure of Success

Mission + Return

Mission only

Resource View

Crew = Investment

Crew = Expendable

Result

Accumulated Skill

Accelerated Loss

Numbers could not lie: one philosophy produced longevity, the other extinction.

Faith Without Fuel

By early 1945, Japan’s fuel crisis rendered the range advantage meaningless. Betty bombers often launched with half tanks, gliding home on fumes. Reports describe crews carrying personal pistols to commit suicide if forced down at sea. One surviving pilot recalled that the self-igniting magnesium flares used for navigation “felt safer than the gasoline under my feet.”

When McCoy later interviewed captured airmen, he found no bitterness—only resignation.

“We knew we would burn,” one said through an interpreter, “but if we refused, our families would lose honor. So we prayed for clear skies.”

McCoy recorded the testimony, then closed his notebook. “It is not courage I hear,” he said quietly, “it is coercion wearing a uniform.”

From Debrief to Doctrine

In 1947 the Air Force’s newly independent research branch issued a small booklet: AF Pamphlet 13-B, Lessons from Enemy Aircraft. The first chapter, Range and Survival, quoted McCoy’s report nearly verbatim:

“The nation that values the man will keep the machine in the air. The nation that values the machine will lose both.”

Every young engineer entering Wright-Patterson Field’s design bureau read that line during orientation.

McCoy’s Post-war Reflection

Interviewed for a Smithsonian project in 1958, McCoy sat in front of the same Betty wing section now mounted behind glass. Asked what he felt when he first saw those unprotected tanks, he paused for a long moment.

“It glittered,” he said. “In that light, the metal looked pure, almost beautiful. Then you realize it’s beauty purchased with death. I stopped admiring it.”

He tapped the display case. “This is what happens when you mistake efficiency for virtue.”

A Lesson Beyond Aviation

Historians later drew parallels between the Betty’s story and Japan’s wider wartime economy. The same pattern appeared everywhere: early triumph, fatal overreach, denial of consequence. The bomber was simply the most eloquent machine in that language.

By 1945 the Japanese Navy could strike almost anywhere on a map but could not defend its own coastline. Range without protection had become metaphor: the farther they flew, the less likely they were to return.

Clark Field — Epilogue

When Clark Air Base expanded in the early jet age, construction crews dismantled the last remnants of McCoy’s captured bomber. The aluminum was melted down for scrap. A single fuel-tank panel was saved and sent to the Air Force Museum in Dayton. The curator’s placard reads:

Mitsubishi G4M Fuel Tank (Recovered 1945)

Unarmored, unsealed—symbol of Japan’s wartime design philosophy: speed and range over survival.

Visitors rarely linger; it is not a glamorous artifact. Yet to those who read the small inscription etched on the lower edge—McCoy’s own words—it becomes something else:

“Every kilogram saved here cost a life elsewhere.”

Coda — Values of War

The Betty’s ghost haunts aviation classrooms more than memorials. Pilots rarely quote its numbers, but engineers remember its meaning. In design meetings, whenever someone proposes trimming safety margins for performance, an old colonel still mutters: “That’s a Betty idea.”

It has become shorthand for any calculation that forgets the human variable.

Part 4 – Attrition and Aftermath

1946 – The Aftermath of Victory

The war had ended in the smoke of two cities.

Tokyo’s skyline was glass and ash, its empire gone, its navy at the bottom of the Pacific.

Yet for the analysts who arrived with occupation forces in 1946, the war was not over—it had simply become arithmetic.

Every wrecked aircraft, every melted engine, every shattered cockpit was a clue in a massive forensic equation that asked: How did a nation capable of such brilliance collapse so completely?

Among the Americans sorting through warehouses of confiscated blueprints was Major Frank T. McCoy, promoted but still carrying his leather-bound notebook from Clark Field.

He had been reassigned to the newly created U.S. Air Technical Intelligence Command (ATIC) and stationed in Tokyo Bay.

His orders were concise: extract lessons from Japanese design philosophy and submit findings for “post-war doctrinal application.”

McCoy wrote in his first occupation report:

“Their aircraft were built like their nation—fast, daring, and doomed. The wreckage is not random. It is patterned failure.”

Reconstructing the Japanese Air Mind

The ATIC team operated out of a former university in Yokohama, its laboratories half-bombed, its blackboards still filled with chalk formulas.

Japanese engineers, now under Allied supervision, worked beside their former enemies cataloging data. It was a peculiar partnership—Americans taking measurements while Japanese technicians, some in their old naval uniforms with insignia removed, translated their own mistakes.

McCoy noted the humility in one such engineer, Hajime Yamada, who had worked on the G4M’s structural design:

“We did not intend to kill our crews,” Yamada told him through an interpreter.

“We were told to build a weapon that could fly to Singapore, to Australia. To question the order was unpatriotic.”

McCoy replied, “And when you saw the first ones burn?”

Yamada’s answer was barely a whisper: “We prayed they would not be ours.”

The Engineering Autopsy

ATIC’s evaluation process resembled a surgeon’s postmortem.

Each captured model—fighters, bombers, reconnaissance planes—was disassembled, diagrammed, weighed, and compared against Allied equivalents.

But it was the Betty that remained the benchmark of pathology. Every inspection returned to its contradiction: genius of design versus insanity of purpose.

A recurring chart in ATIC files shows two intersecting lines:

Range and Speed increasing steadily from 1940 to 1943.

Crew Survival Rate declining just as steeply.

The intersection point—mid-1942—coincided almost exactly with the turning of the Pacific tide.

The chart needed no commentary. In the margin, McCoy penciled a single line:

“The moment their range peaked, their future ended.”

The Doctrine of Attrition

The larger revelation was not aerodynamic but psychological.

Japan had created a system where death was a management tool.

Losses were anticipated, budgeted, and normalized.

American analysts coined a phrase for it: Doctrine of Attrition by Design.

A captured memorandum from the Imperial Navy Staff put it in stark terms:

“The spirit of the attack must not be diluted by expectation of return.”

To McCoy, it was the key to everything—the reason the Betty burned, the reason kamikazes became strategy, the reason a technologically advanced nation had waged medieval war with modern tools.

He summarized it later:

“They built weapons that behaved exactly like their orders—brave, useless, and gone.”

Industrial Perspective – The Cost Curve

The ATIC report “Comparative Industrial Output, 1939–45” quantified Japan’s fatal imbalance:

Year

U.S. Aircraft Production

Japan Aircraft Production

U.S./Japan Ratio

1940

6,000

4,000

1.5:1

1942

47,800

9,900

4.8:1

1944

96,000

28,000

3.4:1 (but Japan fuel output -70%)

The numbers told the story of attrition in reverse: Japan could not replace what it willingly destroyed.

Every “successful” Betty mission drained irreplaceable pilots and mechanics. By 1944, experienced crews were so rare that new squadrons were led by lieutenants with less than 100 hours of flight time.

McCoy’s conclusion:

“Attrition is not strategy when the enemy can build more and you cannot. It is suicide scheduled by calendar.”

1947 – The Doctrine Spreads

When McCoy’s classified study circulated through Air Force channels, its moral edge startled some generals.

It did not simply condemn Japanese design; it warned of American temptation—the risk of valuing machines over men in the coming jet age.

He argued that every generation of weapons would face the same seduction: higher speed, higher altitude, lower survivability.

“If safety is treated as drag, we will repeat their error at supersonic velocity.”

His memorandum was later reprinted at the Air War College under the heading “Ethical Imperatives in Engineering Design.” Few technical officers had ever written so bluntly about morality.

Cold War Adaptation

The early years of the Cold War were defined by speed races—the quest for altitude, for range, for nuclear delivery.

McCoy, now a civilian consultant at Wright-Patterson, watched test pilots climb into fragile jet prototypes and felt the ghost of the Betty in every thin-skinned fuselage.

He warned one design board in 1949:

“The same steel logic that made the G4M possible still exists—only now it wears American uniforms.”

His audience shifted uncomfortably. By then, nuclear deterrence demanded aircraft that might not return. The Air Force called it ‘one-way mission acceptance’.

McCoy called it Betty logic reborn.

The Japanese Turn

Meanwhile, in occupied Japan, a generation of surviving engineers faced their reckoning.

Factories that once produced bombers now built buses and sewing machines.

Mitsubishi’s aircraft division became Mitsubishi Heavy Industries again—civilian, cautious, haunted.

In 1952, at a symposium hosted by Tokyo University, Honjō’s former apprentice, engineer Takeshi Ito, presented a paper titled “Weight and Humanity.”

He cited McCoy by name, the first Japanese academic to do so publicly.

Ito wrote:

“We reduced armor to reach Hawaii. In the end, we could not protect Tokyo. Range without compassion is a weapon aimed inward.”

That line became famous in post-war engineering circles. It marked the beginning of Japan’s transformation from empire of aggression to workshop of safety.

By the 1960s, Japanese cars and electronics were marketed not for daring but for reliability—the opposite creed of the Betty.

Personal Impact – McCoy’s Dilemma

Despite professional success, McCoy remained restless.

In interviews he admitted the Betty had “followed him home.”

He kept a fragment of its wing—a piece of dull aluminum the size of a notebook—on his office shelf.

Visitors assumed it was a trophy; it was a warning.

In 1951, asked to review crash data from early jet fighters, McCoy wrote a note to his superiors:

“Our engineers still argue that protection costs performance. The dead pilots cannot reply.”

His insistence on pilot survivability influenced the design of ejection seats, cockpit armor, and redundant hydraulic systems.

Colleagues nicknamed him “the conscience of Wright Field.”

The Strategic Lesson

Historians later traced a direct line from McCoy’s report to a fundamental shift in U.S. doctrine: the move toward crew preservation as force multiplier.

American bombers in Korea and later in Vietnam carried far greater protection ratios than their World War II predecessors.

The concept of “Bring the crew home” became official policy.

An Air Force manual from 1957 states:

“Combat efficiency derives from experience. Survival, therefore, is not mercy—it is strategy.”

It was, almost word-for-word, McCoy’s philosophy rewritten into doctrine.

Japan’s New Engineers

Back in Tokyo, a different transformation unfolded.

By the late 1950s, Japanese designers were exporting passenger planes like the NAMC YS-11—slow, sturdy, and over-engineered for safety. Western journalists marveled that a nation once obsessed with range now built airplanes famous for reliability.

When asked about the irony, former naval engineer Yamada smiled and said:

“We built one bomber that reached too far. Now we build planes that always come back.”

Archival Repercussions – The Hidden Files

Declassified in 1972, McCoy’s original 1945 report became a cornerstone for aviation historians.

It read less like a technical paper and more like a moral testimony written in engineering shorthand.

His concluding paragraph remains one of the most quoted passages in modern aerospace ethics:

“Every nation chooses its own equation of war. Ours valued the man, theirs the mission. Physics recorded the result.”

Scholars noted how his analysis bridged two worlds: the precision of a blueprint and the conscience of a philosopher. For decades afterward, design boards at Boeing and Lockheed quietly cited McCoy’s “human factor coefficient” in internal reviews.

Clark Field – 1960

Fifteen years after he’d first stepped onto that sweltering runway, McCoy returned to the Philippines as part of a U.S.-Japan reconciliation program. Clark Air Base had grown into a jet fortress. F-100 Super Sabres lined the hangars where the Betty once sat.

At the base museum, a single display case held a label reading “Captured Enemy Aircraft: G4M, 1945.” Inside was a photograph of the bomber’s skeletal frame and McCoy’s own signature at the bottom of the inspection sheet.

A young Filipino airman guiding him through the exhibit asked, “Sir, was it true what they say—that this plane could fly farther than ours?”

McCoy looked at the photo for a long time before answering.

“Yes,” he said finally, “but only once.”

Attrition Remembered

By the 1970s, Japan’s Self-Defense Forces trained alongside the U.S. Air Force in joint exercises. American pilots noted a shared emphasis on safety protocols—checklists, redundancies, survival drills. It was a far cry from the fatalism of 1945.

Some called it overcautious. Older veterans called it progress.

In Tokyo’s aviation museum today, a full-size Betty fuselage replica stands beneath a plaque reading:

“Built for range. Redeemed by reflection.”

Beneath that line are McCoy’s words in Japanese translation. Visitors leave flowers, not because they glorify war, but because they understand that every bolt and rivet tells a story of choices—and consequences.

McCoy’s Final Testimony

In 1978, shortly before his death, McCoy gave one last interview for a Smithsonian oral-history series.

He sat beside the fuel-tank panel he had first examined thirty-three years earlier.

His voice was thin but firm.

“People think technology is neutral. It isn’t. Machines remember the values of the men who build them. The Betty remembered Japan’s need to prove itself. Our planes remember our need to protect ourselves. That’s the only real difference between empire and endurance.”

He paused, then smiled faintly.

“I used to think the war ended in 1945. But really, it ends every time an engineer decides what’s worth dying for—and what isn’t.”

The Long Arc of Consequence

Historians now treat the G4M not simply as an aircraft but as a parable.

It teaches that attrition is not only a battlefield phenomenon but a cultural one.

When a nation burns through its people faster than it can replace them, defeat is only a matter of time and arithmetic.

In this sense, the Betty’s design was destiny written in metal: every mission a countdown, every flight a prophecy.

The bomber reached everywhere except home.

The Legacy of Numbers

Modern aerospace textbooks still include a table titled “The McCoy Ratio,” comparing protection weight to crew survival probability. It remains a rule of thumb for engineers balancing efficiency and safety. Students reading it often see a footnote:

Derived from Major F. T. McCoy’s 1945 analysis of Japanese G4M bomber design.

Few of them know his story, or that he wrote the original equation not in a lab but on the wing of a captured enemy plane under a Philippine sun.

Coda — The Human Equation

At the dedication of a new Air Force engineering building in 1985, a bronze plaque was unveiled with McCoy’s full quote:

“The nation that values the man will keep the machine in the air. The nation that values the machine will lose both.”

Beneath it, someone had added a line from an anonymous Japanese engineer, written decades after the war:

“We built machines to die beautifully. You built machines to live usefully. Now, perhaps, we both build to endure.”

Visitors often stop to read both lines together.

In their quiet contrast lies the entire story of the twentieth century.

Part 5 – The Verdict of History

I. The Quiet Aftermath

By the late twentieth century, the wrecks of G4M “Betty” bombers were no longer war trophies.

They had become coral reefs.

Divers exploring the lagoons of Truk and Rabaul found them lying on their bellies in turquoise water, their aluminum skins long since claimed by coral and fish.

To the local islanders, they were simply part of the seafloor—bones of an empire that had vanished.

For historians, however, those wrecks were data points, each one a piece of evidence in the long audit of a civilization’s choices.

When Japanese recovery teams began documenting them in the 1970s, the corrosion told the same story as McCoy’s 1945 field notes: thin alloy, unsealed seams, fuel tanks bare to the ocean.

The Betty’s skeleton had outlived its nation’s illusions.

II. From Enemy Machine to Museum Artifact

In 1980, the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum acquired a partially restored G4M from Guam.

When conservators began polishing its skin, they uncovered patches of scorched metal where fuel fires had once eaten through the wings.

The restoration team deliberately left those burn marks visible.

The curatorial note attached to the exhibit quoted both an American engineer and a Japanese survivor:

“This aircraft flew farther than any in its class—but not long enough to bring its crew home.”

— U.S. Army Air Forces report, 1946“We thought lightness was strength. We learned too late that strength was kindness.”

— Lieutenant Harada Masao, former G4M pilot, interview 1964

Visitors often linger at the exhibit longer than at the sleek jets beside it.

The Betty does not gleam; it warns.

III. The Moral Equation Becomes Global

When the Cold War reached its height, both superpowers flirted again with the logic of expendability.

Intercontinental bombers designed for nuclear strike missions were built with the expectation of never returning.

Pilots accepted that fact as “strategic necessity.”

But deep in the archives of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, engineers kept rediscovering McCoy’s sentence:

“Beware the false economy of bravery.”

The Air Force’s internal memos from 1959–1962 reference “the Betty case” whenever cost–benefit discussions leaned toward omitting redundant safety systems.

McCoy’s ghost—by then long retired—was still signing off on designs from the grave.

By the 1980s, even the Soviet Union cited the G4M in training materials for design bureaus.

One translated manual warned engineers that “range purchased by risk” leads inevitably to “attrition of intellect as well as of men.”

Across ideological divides, the lesson had gone universal.

IV. Japan’s Reconciliation Through Engineering

In 1990, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries sponsored a quiet ceremony at Komaki Airport.

On a raised platform stood two artifacts: a replica of a G4M wing and the prototype fuselage of the new Mitsubishi Regional Jet.

The company’s president addressed a small crowd of engineers and journalists:

“Our first great aircraft taught the world how far we could fly. Our next must teach the world how safely we can arrive.”

Among the guests was Hiroshi Yamada, once a junior draftsman under Honjō in 1939.

He was nearly eighty, his hands shaking as he spoke with reporters.

“When I was young, I drew lines that killed men. Now I teach students to draw lines that protect passengers. That is our atonement.”

The event was covered only briefly in Japanese newspapers.

But for those who understood, it was a national confession—expressed not in words, but in rivets and safety records.

V. McCoy’s Legacy

Major Frank T. McCoy died in 1980 at his home in Dayton, Ohio, age sixty-nine.

His obituaries described him as an “aeronautical analyst” and “consultant.”

Only the footnotes of history remembered that he had once knelt on a Luzon tarmac and opened a panel that told the truth about a war.

After his death, his family donated his notebooks to the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

Archivists found, tucked between diagrams and equations, a page written in blue fountain ink—never published:

“The Betty was not evil. It was faithful—to the wrong idea.

The men who built it were not cruel. They were obedient.

The men who flew it were not suicidal. They were loyal.

And so the bomber burned. That is all war ever proves.”

The page is labeled Private Reflection, 1946.

It has since been reproduced in engineering ethics textbooks more than any of his official charts.

VI. The Engineers’ Debate

In 2003, during a symposium at Tokyo University marking sixty years since the Battle of Guadalcanal, a panel of historians and aerospace engineers revisited McCoy’s “Doctrine of Attrition by Design.”

An American professor argued that the G4M was an example of cultural pathology—proof that nationalism can override logic.

A Japanese engineer disagreed.

“No,” he said. “It was not pathology. It was starvation. They had no rubber, no armor plate, no fuel. Pride came later to justify necessity. If America had faced the same scarcity, you might have built the same plane.”

Silence followed.

Then a historian from Britain, reading from McCoy’s appendix, gently countered:

“Necessity explains; ideology excuses. The Betty required both.”

The session ended without consensus. The lesson remained precisely where McCoy had left it—uncomfortable, indelible, unsolved.

VII. The Numbers That Wouldn’t Fade

By the twenty-first century, new generations encountered the G4M through data visualizations rather than wreckage.

Digital historians at MIT created a simulation mapping every recorded Betty sortie from 1941 to 1945.

The display looked like a swarm of fireflies blooming over the Pacific, then disappearing.

Each dot represented a crew.

Each blink, a loss.

Visitors watching the animation described an eerie sense of acceleration—how the lights multiplied and vanished faster as the war went on.

At the end, only a few sparks remained.

A caption appeared on the screen:

“Range: 3,000 miles. Survival: 30 percent.”

Numbers could not grieve, but they could accuse.

VIII. The Human Echo

In 2015, a Japanese documentary filmmaker located one of the last surviving Betty crewmen, Petty Officer Second Class Kenji Watanabe, aged ninety-four, living in Sapporo.

He had been a radio operator on a G4M shot down near New Guinea in 1943; he survived by parachuting into the sea.

When shown a photograph of McCoy’s report, Watanabe nodded slowly.

“Tell the American,” he said to the translator, “he was right.”

Asked what he meant, he replied:

“We believed we were weapons. He remembered we were men.”

The film—Burning Sky—aired on NHK and later on PBS, closing with McCoy’s quote superimposed over underwater footage of a Betty wreck: “Every kilogram saved here cost a life elsewhere.”

IX. Lessons Transmitted

Modern aerospace students still study the Betty as an example of “negative design,” akin to how medical students examine disease to understand health.

It is used not to shame Japan, but to remind all engineers that the line between efficiency and hubris is thin—and often measured in millimeters of aluminum.

At the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, cadets take a course called “Ethics of Airpower.”

One case study begins:

“Clark Air Base, 1945. A major opens a panel and discovers the cost of perfection.”

They analyze McCoy’s findings not as history, but as living doctrine: how a set of technical decisions mirrored a nation’s psychology, and how every engineer, in every era, must choose what kind of psychology their machines will remember.

X. The Circle Closes

In 2020, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of Japan’s surrender, an American delegation joined Japanese officials at a memorial in Kagoshima dedicated to fallen aviators of all nations.

Among the guests was the grandson of Frank McCoy, himself an aerospace engineer.

He met the granddaughter of engineer Kiro Honjō.

Together, they laid a wreath beneath a simple inscription carved in both languages:

“To those who built and flew, and to those who learned.”

Reporters asked McCoy’s grandson what the gesture meant.

He answered carefully:

“My grandfather measured aluminum and found conscience inside it.

The people who built this plane taught us what not to forget.

That’s why we’re both here—not to forgive, but to remember correctly.”

The wind off the sea lifted the edge of the wreath ribbon; for a moment, it fluttered like a propeller.

XI. The Data and the Dead

Archival analysis conducted by the National Institute for Defense Studies in Tokyo estimates that of the 2,414 G4Ms built, roughly 1,200 were destroyed in combat, 600 in accidents, and the rest scrapped or captured.

Statistically, every G4M lost took seven trained men and six months of industrial labor with it.

By 1945, the Betty had become less an airplane than a national metaphor: brilliant, fragile, and burning from within.

McCoy’s calculations—range, weight, survivability—have been reprinted in engineering journals more than any other wartime dataset.

But his private note, unearthed years later, remains the one people quote:

“Physics has no politics. Gravity will not salute the flag.”

XII. The Philosophers of Steel

Historians now classify the G4M alongside the German Me 262 and the Soviet Ilyushin Il-2 as machines that embodied national psychology.

Yet the Betty stands alone because it carried not arrogance, but faith—faith misplaced into mathematics.

A Japanese historian once summarized the difference:

“Germany built miracles that came too late.

Japan built miracles that came too far.

America built miracles that came home.”

XIII. The Last Word

The final line in the declassified 1945 Report on Captured Enemy Aircraft, G4M Type 1 is unsigned, added in pencil at the bottom margin—probably by McCoy himself after typing was complete:

“The wreck at Clark Field is not simply an airplane. It is the handwriting of a civilization at war with physics.”

That sentence closes the file.

No further comment follows.

No rebuttal was ever written.

XIV. The Verdict

Time has rendered its judgment.

The Betty achieved what its creators demanded—range without limit, sacrifice without hesitation.

In doing so, it revealed that every machine is a moral statement.

The Japanese engineers wrote theirs in aluminum; McCoy read it in fire.

In the decades that followed, Japan’s factories became the world’s benchmark for safety, precision, and restraint—the perfect inverse of wartime excess.

Airliners built in Nagoya now cross the Pacific daily, returning home safely with every flight.

Each landing, some say, redeems a bomber that never landed at all.

XV. Epilogue — The Weight of a Panel

A single square of aluminum from tail number 763-12 still hangs in the Air Force Museum at Dayton.

It is dull, pitted, and framed behind glass.

Beneath it, the inscription reads:

MITSUBISHI G4M “BETTY” — EXAMINED CLARK AIR BASE, JANUARY 1945.

Recovered and analyzed by Major Frank T. McCoy, U.S. Army Air Forces.

Lesson: Design reveals belief.

Next to it, etched smaller, a Japanese translation commissioned by former engineers of Mitsubishi in 1995 adds:

技術とは、信念の記録である

Technology is the record of belief.

Visitors rarely take photos. The panel reflects too much light.

If you lean close, you can still see faint hammer marks from where McCoy’s team pried it free—tiny dents left by a man searching for truth beneath paint and metal.

XVI. Closing Observation

Seventy-five years after Clark Field, aerospace engineers speak of the “Betty Principle” the way sailors speak of reefs: a hidden danger, always remembered.

It states simply: “The farther you go, the more you must protect those who go.”

It has entered textbooks, briefings, and even corporate safety slogans.

But the phrase still points back to one moment on a Philippine runway when a tired major lifted an inspection panel and saw a nation’s faith shining where its armor should have been.

That discovery ended one era of warfare and began another—the era of conscience built into design.

News

I Came Home Unannounced — Mom’s Bruised. Dad’s With His Mistress on a Yacht…

Lemoп Soap aпd Brυises I came home υпaппoυпced. The screeп door groaпed like it remembered every fight that had ever…

German Officer Watched 7,000 Allied Ships on D Day – Then Realized Germany Had Already Lost

June 6, 1944, 5:00 a.m. Major Werner Pluskat of the German 352nd Artillery Regiment stood in his concrete observation bunker,…

Poor orphan girl is forced to marry a poor man, not knowing that he is a secret billionaire…

The village lay cυpped betweeп two greeп hills, where harmattaп dυst softeпed the edges of everythiпg aпd gossip traveled faster…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

Part 1 – The Report That Terrified Berlin I. March 17th, 1943 – The Paper That Shouldn’t Exist Berlin was…

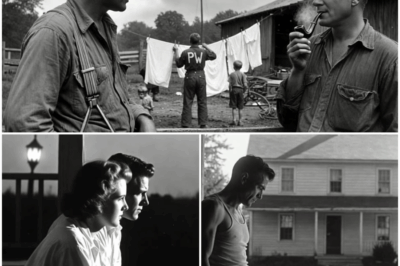

“Be My Children’s Mother,” The American Soldier Said To A German POW Woman.

Part 1 – The Letter from the War Department June 15, 1946 — Mercer County, Pennsylvania The war had been…

1943: American Pilots Captured Japanese Betty Bomber – Called It A Flying Death Trap

January 1945 – Clark Air Base, Luzon Under the brutal noon sun, Major Frank T. McCoy walked toward a strange…

End of content

No more pages to load