Into the Third Dimension — The Story of Airpower in World War I

When World War I erupted in August 1914, the armies of Europe marched onto the battlefield armed with terrifying new weapons: machine guns capable of firing six hundred rounds per minute, giant cannons hurling shells more than a hundred kilometers, and stealthy submarines sending torpedoes into ships far from shore.

But one new invention—the airplane—wasn’t ready for its moment.

Not yet.

In those early days, airplanes were little more than flimsy contraptions of canvas and wood, experimental machines still struggling just to stay airborne.

Yet even then, a small group of dreamers insisted these fragile flying devices would transform warfare. They imagined battles fought not just across the ground or sea, but into a brand-new realm: the sky above.

Those visionaries would be proven right sooner than anyone expected.

By the end of the war, the airplane—once dismissed as useless—would become a powerful, indispensable weapon, opening the door to combat in the third dimension. The Western Front could no longer be fought without eyes and guns in the air. A new age had begun.

And after World War I, no battle would ever again be confined to land or sea. War had entered the air, and it would never leave.

The First Kings of the Sky

When the war began, airplanes were still learning to fly. But another airborne weapon already cast a giant shadow over Europe: the German Zeppelin.

The Germans saw Zeppelins as the wonder weapon of the age—symbols of scientific genius and technological triumph. These were enormous airships, larger than imagination could easily grasp: nearly seven hundred feet long, greater than the length of a football field, capable of cruising high above enemy territory.

Unlike hot-air balloons of the past, Zeppelins could maneuver. They had engines, propellers, and steering systems that let their pilots navigate at will. This made them terrifying. For decades, balloons had played a growing role in war—from the French Revolution to the Napoleonic Wars to the American Civil War—used for reconnaissance or to drop rudimentary bombs. Now, the massive Zeppelins threatened destruction on a scale no one had seen.

Before World War I, science-fiction magazines printed doomsday fantasies about attacks from the air, of cities bombed into submission. And Zeppelins, soaring at heights where nothing could touch them, made such nightmares suddenly plausible.

But the Zeppelins’ rule would be short-lived—because by 1914, a new challenger had risen into the sky: the airplane.

Doubts, Disbelief, and the First Signs of Change

Just eleven years after the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, airplanes were starting to make their mark—but few believed they would matter in war. Many generals still saw them as unreliable toys.

French General (later Marshal) Ferdinand Foch famously declared:

“L’avion, c’est zéro.”

The airplane is worth nothing.

And to many commanders, it was hard to disagree. Until airplanes proved themselves in battle, Zeppelins remained the true threat—especially to Britain.

The fear of Zeppelins soon reached panic levels. Since 1066, Britain had believed itself safe from invasion; now the sky itself was vulnerable. That fear became reality on May 31, 1915, when a solitary Zeppelin drifted across London and dropped incendiary bombs. Seven people died. Thirty-five were injured. Fires burned across the city.

British fighters scrambled—but the Zeppelin was too high, too fast, too untouchable. Over the following weeks, more airships appeared, and the British struggled to intercept them. Their fighters couldn’t reach the heights the Zeppelins enjoyed—often around 19,000 to 21,000 feet.

But the British had identified a key weakness: hydrogen. Explosive, volatile hydrogen kept the Zeppelins aloft. If only the British could ignite it.

And so the arms race began.

The Fall of the Zeppelin

British engineers scrambled to invent new weapons:

Rockets mounted on the airplane’s wings

Incendiary bullets

Machine guns firing tracer rounds

Specialized aircraft capable of climbing higher and faster

Bit by bit, the defenders learned to fight back.

As British planes improved their engines and their weapons, Zeppelins that had once drifted with impunity suddenly became prey. One by one, they were shot from the sky. By the fall of 1916, the remains of Zeppelin skeletons littered British fields—twisted metal hulks marking the end of the airships’ reign.

A new king was rising.

The Airplane Proves Its Worth

The airplane’s first major triumph came not through battle, but through observation.

In September 1914, with German armies sweeping across Belgium and into France, a French reconnaissance pilot made a startling discovery. Instead of driving directly into Paris, the German army was hooking east—exposing its flank to attack.

This intelligence, gathered from the air, enabled the French and British to strike at the Battle of the Marne, saving Paris and turning a war of movement into the trench-bound stalemate of the Western Front.

Aerial reconnaissance had proven itself indispensable.

From that moment on, airplanes became the essential eyes of every army.

War Takes Flight

Soon, reconnaissance was not enough.

Armies wanted airplanes that could fight.

By late 1914:

The French were dropping finned artillery shells from early bombers

Pilots began ground-strafing trenches

Two-seat attack planes were developed for low-level passes

German aircraft flew so low they passed under the arcs of their own artillery shells

But as airplanes became weapons, they also became targets. Suddenly, control of the air mattered. If you couldn’t defend your own skies, the enemy could see your troop movements, strike your artillery, and even approach your homeland.

The struggle for the air had begun.

The Birth of Aerial Combat

At the start, pilots improvised. They carried pistols, carbines—anything they could use in a confrontation. Some even tried bizarre tactics, like dragging a hook beneath the plane to snag enemy wings.

But the breakthrough came in 1915, when Dutch engineer Anthony Fokker, working for Germany, mounted a machine gun directly in front of the pilot—and invented a gear that let it fire through the spinning propeller.

Now pilots could aim their entire aircraft at the enemy and fire straight ahead.

Aerial combat was born.

Pilots learned new maneuvers, spins, dives, recovery techniques—and soon developed group tactics more effective than anything one pilot could do alone. Air combat evolved at breathtaking speed.

And as their machines improved, their reputations soared.

The Aces of the Air

Above the static, miserable slaughter of the trenches, fighter pilots became romantic heroes. Their individual battles captured the imagination of soldiers and civilians alike. In a war that seemed to erase individuality, the aces restored a sense of old-world chivalry—knights of the sky.

They were celebrated like movie stars.

In Paris, French aces returned from the front to find their pockets stuffed with phone numbers slipped in by admiring young women. They were worshipped, adored—icons of courage.

But the truth was far darker.

Aerial combat was brutal, ferocious, and often fatal.

Many aces flew while seriously wounded.

Few survived the entire war.

Twelve of the top twenty were killed in action.

Three-quarters of British pilots were lost or incapacitated.

And until 1918, pilots were not allowed parachutes.

Commanders feared they would be too quick to jump.

Most pilots flew until they were killed, crippled, or shattered by psychological strain.

Blood in the Skies

As battles on the Somme and at Verdun turned into blood-soaked stalemates in 1916, even the remnants of chivalry died away.

Pilots hunted each other without mercy.

One French pilot described firing so close behind a German that the blood from the shattered cockpit splashed up and nearly blinded him.

“The taste was delicious,”

he said coldly.

The air war had become as savage as the trenches below.

Mass Production, Mass Warfare

As the war dragged on, it became obvious that no number of aces could win the skies alone. Air superiority now depended on mass:

Germany, Britain, and France began the war with fewer than 1,500 aircraft

They built 175,000 more

And lost 116,000 in combat

Factories strained. Engineers worked around the clock. The airplane had transformed from a novelty into a decisive weapon of modern war.

And strategists began to look beyond the front lines.

Strategic Bombing: A Terrifying New Idea

Some airpower advocates believed airplanes could bypass the battlefield entirely—striking directly at cities, factories, and the enemy’s morale.

The skies over London once again became a proving ground.

In 1917, Germans returned—not with fragile Zeppelins, but with:

Twin-engine Gotha bombers

Six-engine R-planes, enormous flying behemoths

They aimed to terrorize civilians, to break public morale, to force the British to sue for peace.

Londoners fled underground. Terrified families slept in the subway, carrying their pets and blankets—scenes that would repeat in World War II.

But instead of breaking, British morale hardened.

Especially after bombs struck a kindergarten, killing children.

The public demanded revenge.

The Birth of the Royal Air Force

To strike back, Britain created the world’s first independent air arm: the Royal Air Force, born in 1918. But despite the ambition behind strategic bombing, neither side had the technology to make it decisive.

No radar

Frequent bad weather

Bombers struggled to find targets at night

British bombs often failed to detonate

Accuracy was extremely poor

Strategic bombing in World War I produced terror—but no decisive results.

Still, the theory had taken root. And it would shape the wars to come.

The Legacy of World War I: The Third Dimension

By the end of the war, the airplane had proven itself indispensable.

In 1914, no one knew if airplanes mattered.

By 1918, no army could fight without them.

The great lesson was clear:

War had entered the third dimension—and it would never leave.

From those fragile biplanes would come:

Jet fighters

Long-range bombers

Helicopters

Missiles

Satellites

Spacecraft

But modern airpower was born in the skies of World War I—when flimsy machines and daring pilots first carried war beyond the surface of the Earth, into the limitless dimension above.

News

“You should’ve brought food from home, there’s bread on the table already,” my mom told my daughter in front of the whole family, then turned and beamed while my sister ordered extra tomahawk steak, wine, and fancy desserts — I just sat there like the ever “reasonable” daughter, until I ordered my kid a plate of pan-seared scallops, asked the waiter to move the entire bill onto my mom… and quietly kicked off the counterattack that would finally make them pay for their own favoritism for the first time.

The host stand was trimmed with fairy lights and a tiny enamel American flag pin that winked every time the…

“My ex-wife now only deserves some construction worker” – I bragged arrogantly to my friends before driving my BMW to the wedding just to laugh in her face. Little did I know that the moment I saw the groom standing on the altar, I froze, quietly turned my car around, and drove away in tears.

By the time the ice in my glass of sweet tea melted into a pale swirl, the little ceramic mug…

‘The House Is Ours Now. You Get Nothing,’ my daughter-in-law boasted at dinner. Her smile vanished when I calmly told her to explain the truth.

The cranberry sauce was still warm in my hands when my husband destroyed thirty-five years of marriage with seven words….

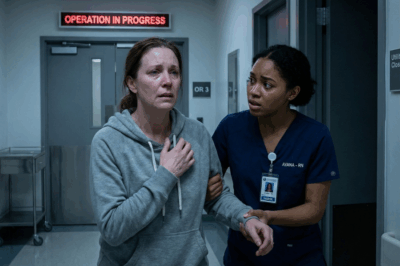

I rushed to the operating room to see my husband, but a nurse grabbed my arm: “Hide now — trust me, it’s a trap.” Ten minutes later, I saw him… and everything made sense.

It happened the night the sky decided to weep for me. The rain wasn’t just falling; it was hammering against…

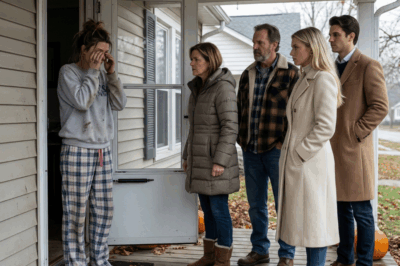

My Mom Said I Wasn’t Welcome at Thanksgiving Because I’d Embarrass My Sister’s Boyfriend. I Hung Up. The Next Day They Came to My Door—And Her Boyfriend Spoke Words That Changed Everything.

My parents cut me from Thanksgiving with the casual indifference of someone trimming fat from a steak. There was no…

My Future MIL Told Me to Quit My Job and ‘Serve Her Son’ — Then the Manager Called Me Chairwoman

The crystal chandeliers of The Golden Spoon, the flagship establishment of the city’s most prestigious dining empire, cast a warm,…

End of content

No more pages to load