The “Missing” Half of the Universe

Until recently, half of the ordinary matter in the universe was missing—hidden, or at least undetected.

And no, I’m not talking about dark matter or dark energy, which make up about 27% and 68% of the universe, respectively. I’m talking about normal, ordinary matter—the stuff that makes you and me, planets, stars, nebulae, and basically everything we can see.

Most of this matter is made of protons and neutrons, which are types of baryons, so this puzzle is known as the missing baryon problem.

We expect the universe to contain about 5% baryonic matter. But when we go out and actually look, we can only account for about 2.5%. So where is the other half?

Why Do We Expect 5% Baryonic Matter?

Your first question might be: Why do we expect the universe to be 5% ordinary matter in the first place?

The answer comes from how well that number explains the relative abundances of the light elements we observe—especially the ratios of deuterium (heavy hydrogen), hydrogen, and helium.

Right after the Big Bang, the universe was full of neutrons and protons zipping around in an incredibly hot, dense, radiation-dominated environment. As the universe expanded, it cooled enough for protons and neutrons to begin fusing into heavier nuclei.

A particularly stable nucleus is helium-4, made of two protons and two neutrons. But to get helium-4, you first have to form deuterium, which is one proton and one neutron. Deuterium is less stable, so early on, as soon as it formed, it was quickly broken apart again by energetic photons.

By about 10 seconds after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled enough that deuterium could survive. Once it did, it rapidly fused into helium-4. The rate of this fusion depended on the density of matter: higher density meant faster fusion.

By around 20 minutes after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled so much that fusion reactions essentially shut down. At this point, the abundances of the light elements were effectively “frozen in”—a snapshot of the early universe.

The result: about 75% hydrogen and 25% helium by mass, which is still roughly what we see in the universe today. Among the hydrogen nuclei, about 26 out of every million were deuterium.

Deuterium is stable—it doesn’t decay—and we don’t know of any astrophysical processes that can create it in significant quantities after the Big Bang. That means virtually all deuterium in the universe today—including the one deuterium atom out of every ~6000 hydrogen atoms in tap water—was formed in the first 20 minutes after the Big Bang, not in stars.

Using the Cosmic Microwave Background

When we look deep into space, the oldest light we can see is the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMB)—the afterglow of the Big Bang, which has been traveling through the universe since about 400,000 years after the Big Bang.

By studying the CMB, we can effectively count the number of photons and calculate the density of radiation in the early universe.

Combining:

the measured ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (about 26 per million), and

the density of photons from the CMB,

we can work out the ratio of baryonic matter to photons. That calculation gives us the result that baryonic matter should make up about 5% of the total energy density of the universe.

Taking a Baryon Census

In the late 1990s, scientists set out to find all of this baryonic matter—essentially doing a cosmic census.

They added up the mass in:

planets

stars

black holes

galaxies

dust clouds

gas clouds

basically everything that could be seen or inferred with telescopes.

The surprising result: everything we usually think of as “stuff” in the universe—stars, planets, galaxies—only accounts for about 20% of all baryonic matter. In other words, that’s only about 1% of the entire universe, when we were expecting 5%.

So where is the rest?

Using Quasars as Backlights: The Lyman-Alpha Forest

Not all ordinary matter glows brightly or is lit up by nearby stars. It isn’t dark matter, but it is ordinary matter that just happens to be in darkness.

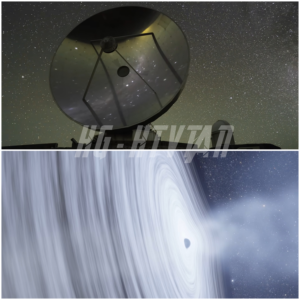

To find these hidden baryons, one approach is to use a backlight—a bright, distant light source that shines through the matter between us and it. For this, quasars are ideal. They can be thousands of times more luminous than entire galaxies.

A quasar’s light comes from the accretion disk around a supermassive black hole at the center of a young galaxy, as it devours matter. Because quasars are so distant, the light we receive from them is heavily redshifted.

For example, consider the Lyman-alpha transition in hydrogen: when an electron drops from the first excited state to the ground state, it emits ultraviolet light with a wavelength of about 121.6 nanometers in the lab. But in light from a distant quasar, the same transition might be observed around 560 nanometers, which is yellow light, due to redshift.

When you look just to the left of that main peak in the quasar’s spectrum, you see many small dips—absorption lines. These are caused by neutral hydrogen gas along the line of sight between us and the quasar. Photons with just the right energy to excite hydrogen from the ground state to the first excited state are absorbed.

Because these gas clouds are at various distances, they have different redshifts. Gas closer to us is less redshifted, so the absorption lines it produces appear at shorter wavelengths. The result is a series of absorption lines at many wavelengths, known as the Lyman-alpha forest.

This forest acts like a one-dimensional map showing where neutral hydrogen gas lies along the line between us and the quasar and how much of it there is.

When we add all that neutral hydrogen gas to our baryon inventory, we get up to almost 50% of the expected baryonic matter.

So…where is the other half?

The Warm-Hot Intergalactic Medium (WHIM)

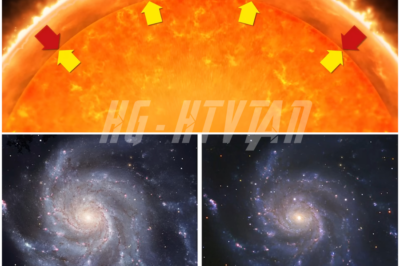

Computer simulations of large-scale structure in the universe suggest that the rest of the baryons are spread out between galaxies in vast sheets and filaments. This low-density material is called the warm-hot intergalactic medium, or WHIM.

Typical properties of the WHIM:

Densities of about 1 to 10 particles per cubic meter

Highly ionized (electrons stripped from atoms)

Temperatures between 100,000 and 10 million Kelvin—hence “warm-hot”

Because the gas is ionized, it doesn’t absorb light in the same way neutral hydrogen does. It mostly emits or absorbs in high-energy ultraviolet or low-energy X-rays, which are hard to observe, especially over large distances.

So actually detecting the WHIM has been a major observational challenge.

Some astronomers used sophisticated techniques to look for it, but recently, a naturally occurring phenomenon helped us finally locate the missing baryons.

To understand it, we first need to talk about lightning.

Lightning, Whistlers, and Dispersion

Did you know it’s possible to detect a lightning strike from the other side of the Earth?

Lightning produces a burst of electromagnetic radiation across a broad range of frequencies. We see the visible flash, but it also emits a wide spectrum of radio waves. If you’re near the lightning strike, these radio waves show up as a pulse.

Very low frequency (VLF) radio waves, however, can travel up out of the atmosphere and get guided along Earth’s magnetic field lines, extending several Earth radii into space, and then come back down to the surface in the opposite hemisphere.

When they arrive, they don’t show up as a single sharp pulse anymore. Instead, they’re stretched out into a sound called a whistler. If you convert those radio waves to audio and play them through a speaker, they sound like a descending tone—a sci-fi laser sound. That’s the signal of lightning occurring on the far side of the planet.

What’s happening?

As radio waves travel through Earth’s magnetosphere, they pass through a plasma of free electrons. These electrons slow the waves down, and the effect is frequency-dependent: lower-frequency waves are slowed more than higher-frequency ones. This phenomenon is called dispersion.

Just as a prism separates white light into its component colors, the plasma in the magnetosphere separates radio waves by frequency. A single pulse spreads out into a descending tone: high frequencies arrive first, low frequencies lag behind.

The amount of dispersion tells you how many free electrons the radio waves have passed through.

Fast Radio Bursts: A Cosmic Whistler Test

Now imagine doing something similar on cosmic scales, to find all the ionized baryons in the universe. All we would need is a bright, short-lived burst of radio waves from somewhere in the distant universe.

In 2007, astronomers found exactly that: the first fast radio burst (FRB).

An FRB is a very brief, intense pulse of radio waves—lasting on the order of a millisecond—originating from distant galaxies. These bursts can be unbelievably powerful—billions or trillions of times more luminous than the Sun, albeit for a tiny fraction of a second.

We still don’t know exactly what causes them. Hypotheses include:

Magnetars (highly magnetized neutron stars)

Neutron star collisions

Black hole–neutron star interactions

But for our purposes, the key point is: FRBs exist, and as their radio waves travel through the universe, they are dispersed by free electrons—just like lightning-generated radio waves passing through Earth’s magnetosphere.

By measuring how dispersed the FRB’s signal is when it reaches Earth, we can estimate the total number of free electrons (and thus ionized baryons) along the line of sight between us and the FRB.

A recent paper in Nature did exactly this. The researchers:

Measured the dispersion measure of several FRBs—essentially, how much the low-frequency waves were delayed compared to the high-frequency ones.

Determined the redshift (distance) of their host galaxies.

They found that the more distant the FRB, the greater the dispersion of its signal, which is exactly what you’d expect if the bursts are traveling through a universe filled with ionized baryons.

Using their measurements, they were able to estimate the total amount of baryonic matter between us and those FRBs, including the ionized particles in the WHIM.

Their result? It matches the expected value of about 5% baryonic matter in the universe.

They found the missing baryons. Roughly half of all ordinary matter is in the warm-hot intergalactic medium, just as the simulations predicted.

What This Tells Us About the Universe

One thing that surprised me in making this video was realizing how little of the universe’s ordinary matter ended up in stars, galaxies, and planets—what I usually think of as “the stuff of the universe.”

Only about 10–20% of all baryonic matter ends up in those structures. The formation of stars and galaxies is actually a pretty inefficient process.

This discovery is another major success story for science. Computer simulations that were run decades ago, predicting the WHIM and its properties, have now been confirmed by observation. The people who worked on those models deserve real recognition.

It also highlights a key difference between how many scientists and non-scientists react to results. Non-scientists often like being right—they enjoy it when reality matches their expectations.

Scientists, on the other hand, often prefer to be wrong, because discrepancies between prediction and observation can point the way to new physics and deeper understanding.

In this case, though, we’ll have to be satisfied with being right.

News

How did they actually take this picture?

This is an image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, known as Sagittarius…

What would actually happen if a star exploded near Earth?

The closest star to us is, of course, the Sun. It’s not going to explode, but if it had about…

Was General George S. Patton, America’s most famous WWII general, murdered in December 1945? And why?

It’s no exaggeration to say that George S. Patton was one of a handful of World War II generals whose…

General George. Patton was a dedicated and controversial soldier.

In December 1944, snow blanketed the battlefields of the Western Front. Exhausted Allied soldiers believed, and many generals quietly agreed,…

Japanese Pilots Laughed At America’s ‘Impossible’ Smart Shells, Until VT Fuses Shot Down 5 Out of 6

August 1943, somewhere in the Solomon Islands aboard the USS San Diego, Lieutenant Commander James Russell, chief gunnery officer, stood…

German Pilot Tested Captured American P-47 Thunderbolt – What He Discovered Changed Everything

November 10th, 1943. Afternoon, at Rechlin—Germany’s primary Luftwaffe aircraft testing facility. Hauptmann Hans-Werner Lerche, chief test pilot, walked across the…

End of content

No more pages to load