I didn’t mean to hear the sentence that would rearrange my life. It slid under a door I’d opened for a different reason, caught the air like a splinter, and lodged where no amount of logic or love could pry it out. I had come for a forgotten portfolio—college sketches I thought might be useful for a pitch—and instead, at the bottom of the staircase, half in shadow and half in steam from a pot roast, I heard my father say, in his careful, managerial voice, “Everything goes to Jason.”

The house glowed. It always did at dusk, the curtains humming with warm light, a framed picture of our family on the console table, everyone coordinated as if happiness came in matching sweaters. I stood so still the air felt like glass around me, and my hand curled against the banister until the wood cooled my palm. I expected someone to laugh and say it was a joke, but laughter did come—Jason’s, easy and pleased—and then my father’s calm, unbothered assent, and my mother’s fork touched porcelain like a tiny bell.

“She did pay for my treatment, Steven,” my mother said, a small reminder, as if years could be summarized in a single receipt.

“That was her choice,” my father answered. “You don’t reward someone for doing what they should have done out of love.”

The word love was the dullest knife in the drawer.

I didn’t announce myself. I didn’t go up the final three stairs and ask them to repeat the sentence so I could make sure I hadn’t imagined it. I slipped backward until the floor stopped complaining beneath my feet, found the doorknob by memory, and stepped into the night with my lungs carved hollow. The portfolio stayed where it was. It could wait.

I drove home with the radio off because anything louder than the hum of the tires felt like too much. Streetlights lifted and fell on the windshield like breath. The mind does a strange thing when the ground beneath it shifts: it revisits everything you’ve ever believed to see which parts still stand. I thought of Christmas cards—my mother’s pearls catching the tree lights; my father’s hand on Jason’s shoulder like a stamp of approval; my own smile rehearsed until it looked effortless. I thought of the mountain bike that arrived for Jason at fourteen, glossy and perfect, while mine came from a garage sale and was sprayed the nearest blue to match his. I thought of my father saying, “Jason’s got business in his blood. You’ve got art,” and how the word art, in his mouth, sounded like a viral thing you hoped would pass without damage.

The text came later, when the tea at my elbow had cooled and the apartment made that empty sound you only hear when you’ve turned all the lights off and left your phone face down. It lit the room like a match: Don’t call or don’t come. It’s over between us. No punctuation. No hesitation. The kind of sentence that doesn’t imagine an answer.

I typed two words: Got it.

There was no shattering. People think devastation is loud because that’s how it plays in movies—plates break, women break, thunder breaks. But the worst things are quiet. They seep. They move through the grout of your life and dry there overnight, changing the texture of everything you touch. I sat until the window turned the color of diluted milk. The city was still. A delivery truck groaned somewhere far away. Fog slumped over the street like a blanket someone forgot to fold.

When the first pale light made the countertops look almost clean, I opened the laptop. For a long time I watched the cursor blink as if it could decide something on my behalf. Emails waited. Auto-payments waited. So many small ropes I’d tied between myself and a family that didn’t know my name unless a bill needed paying. I scrolled through their lives in quiet columns: Mom’s prescriptions. A monthly installment plan for treatment—chemo and radiation that took more out of her than any of us admitted aloud. Jason’s business credit card minimums. Two restaurant utility bills. Insurance premiums. I clicked the first cancel button. Then the second. Then the third. Each click had a sound in my head—a clean, precise snip. I didn’t speak until the page stopped offering me new cancellations to make. “Not anymore,” I whispered to the room, and the room, faithful and small, said nothing back.

I checked the balance I had left—months of late nights and early mornings and work that felt like walking a narrow beam across a windy place—and I felt the strangest thing: my chest, light. Emptier, yes, but lighter. I took the proposal I’d carried to the last family dinner—the one where my father had asked for fifty thousand dollars like he was ordering dessert—and spread its pages across the table. Cost analysis. Renovation plans. Branding and material choices that were both durable and kind to the climate. A full, tailored concept for Hayes Family Dining, the very chain of restaurants whose signs, painted in big gold letters, glowed over Portland like a promise. They had called it a waste of time. I decided to see what someone else called it.

“Hey,” I said when the project manager at Pacific Restaurant Group picked up, his voice bright and inquisitive in the morning. “Remember that sustainability concept I mentioned at the conference? I’ve got a full proposal you can review.”

“Tomorrow,” he said. “Can we see it tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow,” I promised, and wrote the word in the air as if it might evaporate before it dried.

I muted my phone when the calls started. First Jason, then my father, then a number that would probably be my mother, as if she had borrowed anonymity to make herself easier to forgive. I watched the phone’s face light and go dark, light and go dark, a tide I refused to name. Words arrived like pebbles thrown at a window.

You selfish brat, fix this.

Restore payments immediately.

Sweetheart, please call. This isn’t like you.

I put the phone face down and made coffee. At noon an email landed from Pacific Restaurant Group with the quiet thrill of possibility—Loved your concept. Can we discuss partnership?—and I closed my eyes because my body didn’t yet know how to hold good news without bracing for impact.

The garage confrontation happened in a kind of half-light, fluorescent fixtures buzzing in the ceiling like insects who refused to sleep. I was walking toward my car, tote bag heavy with samples and specs, when Jason slid out of the shadows as if he’d been rehearsing the moment.

“You’ve been ignoring us,” he said, jaw set like a punch line.

“I’ve been busy,” I answered, because truth, even when small, tastes better than any excuse.

“Turn the payments back on.”

“No.”

He stepped closer, the old smell of cologne and fried oil lingering on his jacket. For a second the years thinned, and I saw him at seventeen with a dented car and a second one on the way within a week, while the ticket on my windshield had cost me the privilege of driving for a month. The math had always worked this way: things flowed toward him.

“You think you can just walk away? You think you’re better than us?” he said, voice wobbling, and there it was—the fear under the fury, the quiver anyone would miss if they hadn’t spent a lifetime collecting such moments the way other people collect china.

“No,” I said. “I think I finally stopped pretending we’re family.”

Footsteps swung around the corner—Tom from my office, and two others, their conversation snagging on the scene we were making. “Everything okay, Tina?” Tom asked, easy as always.

Jason looked at them, then back at me. “This isn’t over.”

“It is,” I said, and didn’t watch him leave because some exits only look good if you keep them small in your memory.

Three days later, Madison came to my office, mascara blurred into the soft shadows under her eyes. She held the folder like a child holds a book they’re not sure they’re allowed to read. “He doesn’t know I’m here,” she said, and I nodded, the room suddenly careful.

On my desk, the papers unfolded into a map no one had wanted to see: receipts, bank statements, transfer histories from the restaurant accounts to places that were not restaurant accounts. A Rolex here. A Vegas trip there. First-class flights to Miami as if distance could purchase personality. Tens of thousands over three years.

“I thought it was mistakes,” she said, tears scratching at her voice. “I kept thinking the numbers would reconcile if I stared long enough. But it’s him.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it twice—for the loss of who she thought she was marrying, and for the way this would scrape the last layer of polish off my family’s myth.

“I’m leaving him,” she said. “I can’t marry someone who steals from his own family.”

“Then you just gave me exactly what I needed,” I said, and I didn’t hug her because the moment didn’t ask for it; it asked for solidity, for the kind of stillness that says we can make a clean line across a messy page and everything on the far side of the line can become past tense.

The text from my father came as if the last week had never happened: Family meeting. Bridge Cafe. Two o’clock. Not a question. Not an invitation. A directive, written in the same tone that had run our lives since I was a child—a tone that presumed compliance, that considered boundaries a cute trend the younger generation would eventually grow out of.

The Bridge Cafe smelled like rain-damp coats and espresso that had been allowed to burn. The windows held the gray afternoon like a spill. They were already seated when I walked in, in the same formation that had populated every birthday, every holiday, every parenting decision: my mother closest to the window, my father square to the table like a general, and Jason positioned with careless ease, his phone a bright object in his palm.

“You’re destroying this family,” my father began, skipping over greeting, over grace. “Your childish tantrum is—”

“Childish?” I asked, sliding into the chair opposite and laying my bag on the floor. “You mean the part where I stopped paying bills you never asked me about? Or the part where I’m done pretending I don’t see what’s in front of me?”

“Sweetheart,” my mother said, reaching for my hand, and I watched her fingers like they belonged to a stranger who had borrowed my mother’s voice. “We can fix this. Just turn the payments back on.”

“No,” I said, and the word felt like a key turned once, cleanly.

“She’s bitter,” Jason said, and the smile he wore was the old one, the one that usually worked.

I lifted a short stack of papers out of my bag and set them in the center of the table. “Before we say bitter again, read these.”

Jason didn’t touch them first. My father did, and the color on his face traveled from red to the wrong kind of white. “Where did you get this?” he asked.

“From someone who finally decided she’s done cleaning up after him,” I said.

“These are fake,” Jason snapped, as if volume could turn ink into water.

“They’re not,” I said, and let the silence hold him.

“Even if this is true,” my father tried, “it’s family business.”

“Right,” I said. “And family helps family. That’s what you taught me.” I set the second folder on the table—the one they had laughed at a week earlier. “I sold this proposal yesterday,” I said. “Pacific Restaurant Group. Half a million dollars.”

My mother’s fork, lifted as if out of habit, fell and clattered. Jason’s mouth opened and didn’t find words.

“Looks like my useless degree finally paid off,” I said, not gloating, just telling the truth in the plainest way I could find.

“You stole our idea,” Jason said.

“You rejected it,” I said. “Big difference.”

My father looked at me the way a man looks at a door he did not realize was locked until the knob wouldn’t turn. “You’ll regret this.”

“Maybe,” I said, gathering the folders back into my bag. “But at least I’ll regret it on my own terms.”

Outside, the rain had started in a mild, steady way, the sky releasing what it had been holding as if it finally trusted the ground. I stood under it for a moment and let myself breathe in the smell of wet pavement. It’s funny how the body keeps a list of places it can be safely quiet—parked cars, stairwells, the space under a café awning—and adds to that list without ever telling you it’s taking notes. I felt like I’d found another such place.

That night, the apartment didn’t feel like an apology. It felt like a room I’d chosen. I poured a glass of wine and opened my laptop and stared for a long time at the number in my account. It wasn’t revenge money. It wasn’t hush money. It was the purest thing I’d earned in a long time: proof that I didn’t need permission to matter. I closed the laptop and took a sip. Peace has a flavor. In case you’re curious: it tastes like cabernet and clean air.

Six months passed. Not quickly. Not slow. Time did its ordinary, reliable work of putting inches between things. I built out the partnership with Pacific Restaurant Group one clause at a time, one materials list at a time, one meeting where I explained why reclaimed wood can look high-end if you let it, at a time. I slept. I ate like an adult. I bought fresh flowers for the kitchen counter without thinking twice.

Aunt Patricia called when the old story finally collapsed. Her voice was the exact blend of pity and gossip I’d braced for my whole life. “They lost everything, honey,” she said. “All five restaurants gone. Bankruptcy filings. Lawsuits. The works. Jason’s facing charges—embezzlement. Your father’s at a hardware store. Your mother picked up a part-time shift at Macy’s.”

I watched the city from my office window while she spoke. Somewhere, a siren stitched through the afternoon and disappeared. People were laughing down the hall. My team. My team.

“They asked about you,” Patricia said, gentler now. “I think they finally understand.”

Maybe they did. Understanding is its own quiet mercy, but it doesn’t change a single page in the book already printed. I didn’t tell Patricia that. I told her I hoped everyone was okay. When I hung up, the room felt as steady as it had the moment I first said No in a voice that sounded like mine.

Later, I scrolled back through old messages until I found the one that had become a marker in the map of my life: Don’t call or don’t come. It’s over between us. It didn’t make me flinch anymore. It didn’t make my pulse skip a step. It simply reminded me of a version of myself who kept reaching for closed doors believing persistence could turn a lock.

I typed one last message I never sent. I said it out loud to the room, to the counter, to the window, to the woman I had been and the one I was becoming: “Got it.”

People ask about my family and I say normal because it’s easier and because it’s technically true if you look from a distance. Five restaurants across Portland, Hayes Family Dining in big gold letters, the kind of place where a waiter calls you “hon” and refills your coffee without you asking. A mother who kept the books with neat handwriting. A father who had a voice built to be obeyed. A brother who understood early that doors open faster when you don’t look back to see who’s holding them.

From the outside, we looked like a calendar photo: the good sweaters, the cold air warmed by black coffee, my mother’s pearls catching December lights. Inside, the hierarchy ran with the heat vents. You could feel it most in winter when the clay pot on the stove steamed up the windows and my father would say something about Jason’s future in business, as if blood itself could choose a major. I wasn’t quiet because I agreed; I was quiet because quiet was the only thing that didn’t cause more trouble than it solved.

Art was the word they couldn’t love. It lived under my skin like a small light, one that grew brighter when I put a room together the way a room wants to be put together—where the angle of a chair and the line of a window and the texture of a table made sense together like a chord you could sit inside. My father said art like it was an illness I would eventually outgrow. I didn’t outgrow it. I went to design school in Seattle and waited tables at night and tutored freshmen during the day and lived, spectacularly, on instant noodles and caffeine and the single stubborn belief that vision was an inheritance you could choose if you had to.

I sent postcards home, the kind you buy in racks near bookstores—snowy mountains, ferry docks—but nothing arrived in return. My father called once to tell me I could still come back to the restaurants if I wanted to do something real. I thanked him for the offer and breathed through the burn it lit behind my ribs. When I graduated, I came back to Portland, rented a small apartment that made good light out of ordinary afternoons, and took whatever work I could find: an office lobby that needed to look like it belonged to people who knew what they were doing; a restaurant that thought reclaimed wood would make everyone feel welcome as long as no one got splinters; a hair salon where the owner wanted the chairs to look like thrones without being literal about it. Funny how many of my early clients were the same kind of places my father had always believed in, only this time I chose what they would become.

When my mother got sick, I didn’t itemize. We flew to San Francisco for specialists because the local options lacked the machine her doctor wanted. We slept in hotels that smelled like bleach and coffee. We ate breakfast at counters where no one asked questions, and when the bills came, I paid them. Not because anyone said please. Not because anyone said thank you. Because love can be quiet, and mine had learned to be. When she went into remission, she texted, “Thank you for everything, sweetie.” I sat in my car in a parking garage and looked at the sentence until it became a small, dull star. I let it be enough for that day.

Jason called about his food truck after that—big idea, big plans, the kind of pitch that could sell cold lemonade in winter. Six months later, the truck had crashed as hard as his first car, and I wired him twenty-five thousand dollars because I could and because someone always did. A few months after that, something at the restaurants broke—equipment, a critical piece—and I sent another fifteen. He restructured, he bragged. He saved the day. He never once mentioned my money.

Love makes you write checks long after the account is overdrawn. It’s a fact nobody puts on a greeting card because it doesn’t sell, but if you’ve lived it, you recognize it on sight. Every time I told myself I was helping the family, I made a small promise to a version of us that didn’t exist. And still, I kept making them. I can call it loyalty. I can call it hope. It was both. It was neither. It was a habit that wore my name.

When my father asked for fifty thousand dollars at dinner as if it were a slice of pie he’d decided to try, I said I’d think about it and went home to the portfolio in the attic—a set of sketches from school I wanted for a presentation. The plan was takeout, sleep, avoid the argument I knew I’d lose if I engaged it straight on. The plan was not to hear what I heard.

I don’t remember how I drove away that night without running a light. I do remember the feeling of the air changing inside my car, like it does when a storm has already decided where to land. I remember my mother’s silence more than my father’s certainty. The truth about betrayal is that it’s less about the volume of the person speaking and more about the absence of the person who won’t.

The two words I sent—Got it—weren’t a surrender. They were a boundary. They were the first sentence I’d written in my life that didn’t anticipate a reply.

Morning looked ordinary because morning always does. I made the cancellations with a discipline I recognized from rebuilding a room from the studs out. You remove what doesn’t belong, not angrily, just precisely. The list shortened. My house quieted. Somewhere between the pharmacy auto-refill and the restaurant insurance, I felt something unhook. I didn’t celebrate. I breathed.

Pacific Restaurant Group moved quickly. The man on the phone liked what he’d heard at the conference; he liked it even more when the proposal landed in his inbox and turned into a phone call with words like partnership and rollout and timelines. I said yes to a meeting and yes to the contract terms that respected my work and yes to the number that made my hands shake a little when I hung up.

The calls from home multiplied in a way that might have felt flattering if I didn’t know what scarcity does to people who think they are owed. Jason threatened lawyers he hadn’t met. My father demanded compliance he hadn’t earned. My mother pleaded for peace like peace was a switch only I could flip. I kept the volume down and the screen dark.

In the parking garage, Jason’s face held the same fury I’d seen on it since we were kids and I won the kind of attention he wanted—teachers, friends, anyone who liked the way I solved the problem in front of us. He didn’t grab me. He wanted to; I saw the thought in his wrist. He didn’t because three people rounded the corner and because the part of him that still cared about optics—our family’s oldest religion—knew better. “This isn’t over,” he said. It was.

Madison’s folder didn’t surprise me. That’s the part that hurt. Somewhere I had expected evidence to arrive like this, tidy and undeniable, because the numbers had been limping for so long that even a miracle couldn’t have hidden the limp. The clean lines of the bank statements felt like justice. I don’t love that about myself, but it’s true.

At the Bridge Cafe, I watched my family orbit a narrative that had stopped including me and then remembered that I had stepped out of it on purpose. I said the words I needed to say. They said the ones they always say. The documents did a different kind of talking, the kind even my father couldn’t out-volume. When I mentioned the contract—half a million dollars—Jason said I’d stolen his idea. It didn’t matter that he hadn’t read a single page. It mattered that I had, that I had written them, that I had put my name at the bottom and sent them into a world that didn’t require permission slips.

I walked into the rain and let it choose me clean.

Six months later, the façade had fallen. Bankruptcy filings don’t care about family stories. Lawsuits read like weather reports. Charges stick because paper does. I didn’t dance. I didn’t even smile. I looked out the window at a skyline I had helped shape in ways no one in my childhood dining room could have imagined, and I answered emails from people who wanted me for my work instead of my wallet.

People say revenge is sweet. I think they confuse it with relief. Mine tasted like taking a full breath without counting how much oxygen I owed the room.

Sometimes I try to identify the exact moment the myth of our family began. Maybe it was always there, in the way the camera paused a little longer on Jason, or the way my father’s laugh sounded more like approval when Jason made it happen. Maybe it started the afternoon my parents chose gold letters for the first Hayes Family Dining sign—a name big enough to own, lighting big enough to promise—and decided the brand would do as much work as the food. Maybe it was the instant I came home with an acceptance letter to design school in Seattle and my father said, “If you walk away from the restaurants, you walk away from this family,” and my mother nodded a small nod that told me the verdict had been unanimous before I entered the room.

The myth said we were close because we were adjacent. We ate together because we worked together. We posed together because uniforms shrink distance inside a rectangle. We were functional because we survived the holidays without anyone cracking a plate. The myth had staying power. Many do. That’s what makes them useful: they keep the building upright long after the foundation has split.

Standing at the bottom of the stairs that night, I saw the myth from a new angle. It wasn’t a family. It was a business plan, and like most business plans, it had early investors (my parents), a designated golden child (Jason), and a quiet donor with no voting rights (me). Once I recognized the model, I couldn’t unsee it. That’s the thing about clarity—it’s irreversible.

When I turned off the auto-payments, I didn’t imagine myself noble. I imagined myself precise. Money is a story; I edited mine. When I sold the proposal, I didn’t imagine myself triumphant. I imagined myself correct. Work is a language; I spoke mine. When I looked at the phone lighting up with calls I would have crawled across gravel to answer a year earlier, I didn’t imagine myself cruel. I imagined myself consistent. Boundaries are a practice; I practiced them.

I used to want apologies. I pictured my father learning how to say that word the way other people learn new languages—haltingly at first, then fluently, then with an accent strong enough to charm a room. I pictured my mother learning to speak in declaratives instead of agreements, her mouth finding the shape of “no” without looking toward my father for grammar. I pictured Jason realizing the door only opened because people on the other side held it, and offering to take a turn.

What I have now instead are facts. The restaurants are closed. The gold letters came down with a ladder and a rented truck. Jason is facing charges that add up to a story he can’t spin. My father clocks in at a hardware store where the aisles are numbered and the customers know how to ask for what they need. My mother smiles at a register in the perfume section where women trade one kind of dream for another in bottles no bigger than a fist. Facts aren’t apologies, but they are clarifying. They are evidence. They are, in their way, respectful: they don’t pretend.

If you asked me for a moral, I would resist the question because stories like mine are less parables than maps. They don’t tell you what to do; they show you where you might be. I can tell you this: peace will not arrive with other people’s permission. It will not arrive with gold letters. It will not arrive with a family meeting. It will arrive when you cancel the thing that is quietly draining you, when you sell the thing they called useless to someone who knows its worth, when you walk into the rain and realize the sky is not interested in whether your hair frizzes.

When people ask now what my family was like, I sometimes say normal and sometimes say complicated and sometimes say “we had five restaurants” because details can feel like answers when they are really only setting. The truth, if I’m brave enough to say it plain, is that my family taught me exactly what it meant to be invisible—so thoroughly that I could spot invisibility in a room the second I entered it—and then, by accident, they taught me the opposite. They taught me that love without respect is a problem with no solution, and that the word daughter doesn’t guarantee either one.

There’s a picture on my kitchen shelf of me at seven, in a red sweater my mother chose and a smile she probably reminded me to wear. In the background, Jason is making a face that used to make everyone laugh. When I look at the photo now, I don’t narrate. I don’t correct the record. I don’t imagine a different childhood. I imagine only this: that the little girl in the sweater would like the woman who lives here now. She would like the quiet. She would like the way the morning sun falls across the counter like a benediction. She would like the way the air feels honest.

If I could tell her something, I wouldn’t warn her about the night by the stairs or the sentence that would change everything. I would tell her the simplest thing I know that is also the hardest to practice: You can’t make people see you by becoming smaller. And then, because she is seven and because she is me, I would teach her how to draw a room so it welcomes whoever walks into it, including herself.

On certain mornings, when the city is still soft and the water on the street looks like glass, I take my coffee to the window and read the sentence I didn’t send the night everything became both worse and better: Got it. I like that it isn’t dramatic. I like that it doesn’t explain. I like that it contains both grief and clarity without making a spectacle of either. It’s the kind of sentence that understands what the body understands long before the mind does: some doors, once closed, are best left closed, not out of anger, but out of respect for all the rooms you haven’t entered yet.

If you’re holding a phone with a message that tries to turn your love into an invoice or your loyalty into a lever, here is my unprofessional, unlicensed advice: you are not a switch to be flipped. You are a person. Your life is a room you’re allowed to furnish. Put the chair where the light is good. Throw out the table that bruises your thigh every time you walk past it. Keep the window clear so you can see the weather coming. And if someone insists you are only valuable when you pick up the check, cancel the subscription. Let the invoice return to sender.

I can catalog the things I didn’t do after that text as a way of telling you who I am now: I didn’t plead. I didn’t argue. I didn’t audition. I didn’t produce a spreadsheet of generosity to make my case. I didn’t post a subtweet for strangers to admire. I didn’t turn my pain into an instrument. I turned it into space. Space is expensive in any city. I had been paying for other people’s for so long that I had forgotten how to purchase my own.

When the next email from Pacific Restaurant Group came in—We’d love to roll this out to the first cluster of locations by fall—I thought, for once, about scale in a way that didn’t frighten me. I used to believe that everything large could swallow me. What I believe now is practical: anything large can be measured, broken into parts, solved one part at a time. If I can make a bad room better, I can make a good room precise. If I can make a room precise, I can make a chain of rooms honest. The math is far kinder than the one I grew up with.

I don’t keep the gold letters from the restaurants. They were never mine to begin with, and besides, they belonged to a story that made other people large by making me small. What I keep is quieter: a copy of the proposal with my name on it; a list of cancellations that remind me I can delete as cleanly as I can design; a text I didn’t send; a memory of rain that didn’t ask my permission to fall.

If you came over for dinner—if you were a friend and not a stranger with a microphone and a theory about why some daughters leave—you would find a table that doesn’t bruise, chairs that forgive, a window that tells the truth about the weather, a vase with flowers I didn’t elect to earn. We’d eat something simple. We’d talk about the city and how it manages to be both difficult and beautiful on the same block. If you asked what happened with my family, I would hand you a napkin and say I overheard a sentence and chose a different one in return. The rest is details and paperwork.

People say closure like it’s a door that clicks shut. I think it’s more like a room you leave because the air is no longer good for you. The door remains unlocked. You can return. You can’t breathe there. Both can be true. When the calls stopped coming—not because they forgive me or because I forgave them, but because the story moved on without our consent—I stood at the window again and felt the kind of stillness I used to confuse with fear. It wasn’t fear. It was the absence of begging. It was the presence of choice.

And when, on some future day, I need to remind myself how quickly a life can tilt, I won’t replay the pot roast or the staircase or the matchstick glow of a text. I will pour coffee. I will open the laptop. I will read the proposal text where it says Materials: durable, locally sourced, sustainable. I will picture rooms at scale, honest and warm, where strangers become good to each other because the space invites it. I will remember the family I came from and the one I build now, which is not a bloodline but a blueprint, not Christmas cards but contracts that do not require me to be less to be loved.

I will remember that I answered the sentence designed to erase me with a sentence that restored me. Got it. Two small words that, when spoken with a whole life behind them, can sound like a door opening somewhere you didn’t realize a door existed. And I will go there. I will step through.

News

After I Refused To Pay For My Sister’s $50k Wedding, She Invited Me To A “Casual Dinner.” Three Lawyers Were Waiting With Documents. She Said “Sign This Or I’ll Ruin You,” And I Said, “Meet My Husband.” What He Handed Them Shut Everything Down.

That title belonged to my younger sister, Morgan—the golden child, the homecoming queen, the girl with the 4.2 GPA who…

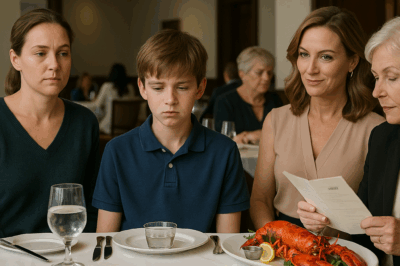

“Your Kids Can Eat When They Get Home,” My Mom Said, Tossing Them Napkins While My Sister’s Daughters Unwrapped $65 Pasta And Dessert Boxes. Her Husband Laughed, “Should’ve Fed Them First.” I Just Whispered, “Copy That.” When The Waiter Returned, I Stood Up And Said…

My mother tossed two paper napkins across the linen like she was flicking crumbs to a pair of strays. The…

I Went To My Mountain House To Relax, But Found My Sister, Her Husband And Her In-Laws There. She Yelled, “What Do You Want, You Lonely Parasite?! I’m Calling 911!” I Said, “Go Ahead.” She Had No Idea This Call Would Ruin Her Life…

I was thirty‑five and, for the first time since my company found its footing, I had carved out a clean,…

“We Don’t Feed Extras,” My Sister Said, Sliding a Water Glass to My Son While Her Kids Had Lobster Platters. Mom Added, “You Should Know Your Place.” I Just Smiled and Said, “Noted.” When the Chef Arrived…

The reservation at Meridian was for 7:00—prime time by any standard. Every table was full. The dining room buzzed with…

I Was Dragged Into a Baby Shower to Shield a Mom From Her Ex Who Tried to Burn Her Home

Part I – The Stranger’s Request I was walking down Maple, minding my own business, when two women I’d never…

MIL Lost It at My Baby Shower & She Insulted Me, Tried to Name My Baby but Ended Up Getting Arrested After Making a Scene.

Part I – The Announcement When I first saw the faint pink lines appear on that test, I cried —…

End of content

No more pages to load