I never thought retirement would lead me here—standing in my own lake house at midnight, watching my daughter toast champagne with a real estate agent while my wife sobbed alone in the bedroom. But that’s exactly where thirty‑two years as a fire chief in Thunder Bay got me. The same instinct that made me check smoke detectors twice, that made me walk a full circle around a burning building before sending my crew in, was the instinct that made me get in my truck and drive three hours through northern darkness because something in my chest said, “Go now.”

It was supposed to be Thanksgiving week.

Margaret and I had spent decades building our life together in northern Ontario. She taught second grade for twenty‑eight years at a small elementary school where the Canadian flag snapped in the wind every morning and kids tracked snow into the hallway from October to April. I worked my way up from rookie firefighter to chief at the Thunder Bay Fire Department. Our life was simple: church on Sundays, barbecues in the backyard in July, the smell of wet wool mittens on the radiator in January.

We raised our kids in a modest red‑brick house on a quiet street where snowplows were just part of the morning soundtrack and hockey nets lived permanently at the end of driveways. Summers, when the humidity climbed and the city smelled like warm asphalt and lake breeze, we drove out to Lake Superior and dreamed about owning a little piece of shoreline of our own.

Twenty‑five years ago, we made that dream happen. The place we found wasn’t much—just a weather‑beaten cabin on a rocky point along the north shore of Lake Superior, with a sagging porch and windows that rattled whenever the wind came hard off the water. But when we stood there that first day, the lake stretching out like an inland ocean, the American shore a faint ghost on the horizon, we looked at each other and knew: this was it.

Powered by

GliaStudios

I rebuilt that cabin with my own hands. Every deck board, every window frame, every shingle. I hauled lumber in the back of my pickup, worked weekends after twenty‑four‑hour shifts at the station, hammered and sawed until the calluses on my hands split and bled. Margaret planted the garden, chose every paint color, hunted down old‑fashioned light fixtures at antique shops in Duluth on our occasional cross‑border trips. We argued about where to put the couch and laughed about it later, sitting side‑by‑side with mugs of hot chocolate while storms rolled in from the lake.

The lake house was supposed to be where our grandchildren would learn to fish off the dock, where we’d grow old watching sunsets burn orange and purple over the water, where Thanksgiving would always smell like turkey, wood smoke, and pumpkin pie.

When I finally retired at sixty last spring, we thought we’d earned our peace. My last day at the station, the guys strung up a banner in the bay and the city gave me a plaque. Thirty‑two years. I stood there in my dress uniform, listening to speeches about bravery and service, thinking about every face I couldn’t see in that room anymore. When I turned in my pager and radio, my belt felt too light.

“Now you can actually stay more than one night at the lake,” Margaret said, sliding her hand into mine in the parking lot as we walked under a sky that smelled like rain coming off Superior.

We started calling it “home” without even realizing we’d done it.

By November, we’d made a plan. Margaret would drive up on Monday with our daughter Jessica and her husband Marcus to get the place ready for Thanksgiving. Our son Tyler would arrive Thursday morning with his wife and two kids, bringing the chaos and noise we now needed more than we wanted to admit.

I was supposed to follow on Thursday. The department had planned a small retirement party for the night before—cake in the training room, a slideshow, a few kind words. At least, that was the idea.

Tuesday afternoon, I got the call.

“Chief, I am so sorry,” the new deputy said. “The city moved up a budget meeting. We have to cancel the party. We’ll reschedule in the new year.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I told him, and I meant it more than he knew. I was never comfortable being the center of attention. I’ve always felt more at ease behind the hose line than behind a microphone.

But when I hung up, there was an odd emptiness in the house. The kind that makes you hear the furnace kick on and the refrigerator hum and suddenly realize how quiet your life has become.

I looked at the calendar: Tuesday. Three days before Thanksgiving. Margaret had left the day before, her car loaded with groceries and bedding.

For a few minutes I just stood there, staring at the little note she’d written and stuck to the fridge—”Don’t forget your heart meds. Love you.”—and the unease started. A little flicker at first, like the first wisp of smoke curling out from under a door.

I tried to shake it off. I made a sandwich. I turned on the TV. The local news showed footage of a moose wandering through a parking lot in town. It didn’t help.

Thirty‑two years of walking into chaos had taught me one thing: there are times you listen to that feeling.

By six o’clock, I was standing in the driveway with my overnight bag.

“You’re really going up tonight?” my neighbor called, leaning against his truck across the street, breath puffing white in the cold.

“Yeah,” I said. “Figured I’d surprise them.”

I didn’t mention the tightness in my chest.

The drive from Thunder Bay to the lake house took nearly three hours in good weather. That night, the sky was clear but the November darkness came down like a curtain. The highway out of town slid into long, lonely stretches of forest. The kind of night where the only light comes from your headlights, the stars, and the occasional oncoming truck.

I passed logging rigs throwing up plumes of snow dust, their chains rattling. On the stretches between towns, the radio faded in and out. American stations from across Superior flickered through: a country song about lost love, an ad for a car dealership in Duluth, a preacher warning about the end times.

Twice I called Margaret. Both times it rang and went to voicemail.

Not unusual, I told myself. Cell service was patchy out by the shore. Sometimes the wind and the water swallowed the signal whole.

But the feeling didn’t go away. It crawled along my ribs like a slow burn.

Call it thirty‑two years of reading smoke patterns and knowing when a situation was about to flash over.

By the time I turned off the highway onto the narrow gravel road that wound through the pines toward our place, my hands were tight on the steering wheel. Frost sparkled along the ditches. The lake wind had that particular bite that meant snow wasn’t far away.

I eased the truck down the last curve and pulled into the driveway.

My stomach dropped.

The house was lit up like a Christmas tree. Every window glowing. The porch light blazing. Warm yellow light spilled across the front yard and the parked cars—Margaret’s sedan, Jessica’s SUV, and a dark luxury car I didn’t recognize.

Margaret usually went to bed by nine. She’d lecture me about “wasted hydro” if I left even the hallway light on.

Something was wrong.

I left my bag in the truck. The night air hit me, sharp and clean, carrying the cold, metallic smell of the lake. My boots crunched on frost‑covered gravel as I walked toward the front steps.

That’s when I heard it.

Laughter.

Not just a chuckle, but loud, celebratory laughter coming from the back deck. High, excited, champagne‑fueled laughter that didn’t fit the quiet, pine‑ringed darkness of our usual nights at the lake.

And underneath it, fainter, like a sound coming from the next room over in a fire, I heard someone crying.

I froze.

I didn’t go through the front door.

Thirty‑two years as a fire chief teaches you to never walk straight through the most obvious entrance when something feels wrong. You circle the structure. You look for signs—heat against windows, shadows moving where they shouldn’t.

I slipped around the side of the house, staying close to the siding where the shadows were thickest. The deck wrapped around the back, overlooking the black stretch of Lake Superior. The water was invisible, but I could hear it, the low, constant shush against the rocks.

I crept up to the corner and looked.

Three figures stood on the deck, silhouetted against the porch light.

Jessica, thirty‑two, my little girl who used to skate on the community rink in a pink helmet, now in a fitted blazer and heeled boots, her dark hair catching the light. Marcus, her husband of four years, tall and athletic, gesturing wildly with a champagne glass as if he were closing a big sale. And a man I didn’t recognize, older than Marcus, silver‑streaked hair, wearing an expensive charcoal suit despite the hour and the lake chill.

They each held fluted glasses, the pale gold champagne catching the light. The deck table was cluttered with a laptop, a leather portfolio, and a bottle in an ice bucket. Beyond them, the November sky arched black and endless, the faint glow of American lights far across the water.

“To the new Lake Superior Resort and Spa,” Marcus said, raising his glass.

His voice carried in the cold air like a radio call.

“This place is going to make us a fortune. Prime waterfront property. You can’t beat it. Americans will pay anything to feel like they’re roughing it in Canada as long as the sheets are high‑thread‑count.”

The suited man clinked his glass against Marcus’s, eyes sharp.

“Your parents really won’t be a problem?” he asked, skepticism curling around his words.

Jessica swirled her champagne, lips pursed, looking out over the lake like a woman surveying her kingdom.

“My father’s sixty,” she said, and the sound of her voice sliced through me. There was a chill in it I’d never heard. “They’re both showing signs. Mom forgot to pay the utilities last month. Dad can’t remember appointments. We’ve got documentation. The memory clinic appointment is set for Friday in Thunder Bay. Once that’s on record, it’s straightforward.”

Ice flooded my veins so fast I almost staggered.

Memory clinic?

“And the legal documents?” the stranger pressed.

Marcus smiled the smooth, confident smile I’d never trusted.

“Already handled,” he said. “Power of attorney for health and finances. Once the cognitive assessment comes back showing decline, it’s just a formality. We become their legal guardians. They move into that nice assisted living facility in Thunder Bay—indoor pool, bingo, the whole package. We develop the property. Everyone wins.”

“Except them,” the stranger said quietly.

Jessica shrugged, took a calm sip.

“They won’t even know the difference in a few years,” she said. “This is for their own good. They shouldn’t be living out here alone at their age. Winters on this lake? It’s dangerous. We’re protecting them and unlocking the real value of the asset.”

“Asset.”

That’s what she called the home where she learned to swim.

I’d run into burning buildings where the roof could have caved in any second. I’d held pressure on wounds on the side of Highway 11 in snowstorms while paramedics fought for a pulse. I’d stared down warehouse fires that threatened to take out an entire block.

Nothing—not one of those moments—had prepared me for standing in the shadows of my own deck and hearing my daughter talk about me like I was a problem to be managed, an obstacle between her and a payday.

Before I knew I was moving, I stepped onto the deck.

The wood creaked under my boots.

“Their age?” I said. My voice sounded strange in my own ears—steady, level. “I’m sixty, Jessica. Not ninety.”

All three of them spun around.

The champagne glasses froze midair like a photograph. The suited man’s eyes widened. Marcus’s smile shattered. Jessica’s face went from flushed and animated to white in a heartbeat.

“Dad, I—” she stammered. “We… we weren’t expecting you until Thursday.”

“Clearly,” I said. My hands were in my pockets, but every muscle in my body felt coiled.

I looked at each of them in turn, the way I’d look at a room full of council members when explaining why we needed a new truck.

“Someone want to explain what I just heard?” I asked.

Marcus recovered first. He always did. The man had quick reflexes when it came to words.

Four years ago, when Jessica first brought him home for Thanksgiving, I’d done my research. Former sales executive. Big ideas. A string of “almost” ventures. A lot of charm, not much substance. The kind of man who always seemed to be one deal away from everything turning around.

Jessica loved him. Margaret said we had to give him a chance.

So I’d kept my doubts to myself.

Now, standing on that deck, listening to the November wind and the faint rush of Superior below, I regretted that more than any mistake I’d made at a fire scene.

“Bob,” Marcus said, forcing a smile as he stepped forward. “Good to see you.”

He extended his hand.

I didn’t take it.

He let it drop, fingers tightening around the stem of his glass instead.

“We were just discussing some options for the property,” he said smoothly. “Investment opportunities. Ways to help you and Margaret.”

“Options for my property,” I said, my voice flat. “The one I rebuilt with these hands while you were still figuring out how to expense your lunches.”

I held up my scarred palms.

Jessica flinched.

“Dad, please,” she said, setting her glass down too fast. The stem rattled against the table. “We need to talk. Mom’s not doing well.”

“Really?” I asked. “Because I just heard you say she’s well enough to be forced out of her home so you can pour concrete where her lupines grow.”

“She forgot to pay the utilities,” Jessica snapped. Her voice rose, sharp edges exposed. “The power was almost shut off. What if that had happened in winter? You could have frozen to death out here.”

“I paid the utilities three weeks ago online,” I said, each word measured. “Like I do every month. Hydro, gas, property tax. All on auto‑pay except the ones that still insist on paper.”

I could feel my pulse in my throat but my voice stayed calm. Thirty‑two years of incident command teaches you how to keep your head when everything in you is about to catch fire.

“Try again,” I finished.

The stranger cleared his throat.

“Perhaps I should go,” he said, already half turned toward the stairs.

“No,” I said, turning to him. “Who are you?”

He hesitated, then squared his shoulders.

“Donald Breenidge,” he said. “Real estate development. We—” He glanced at Jessica and Marcus. “We were discussing a potential project.”

“On my property,” I said.

He swallowed.

“Look, I didn’t know this was—” He gestured vaguely between me and my daughter. “I’ll leave you to your family discussion.”

He left fast, cutting across the deck and down the steps. A moment later I heard his car door slam, the engine start, and headlights sweep like search beams across the pines as he backed down the driveway and disappeared toward the highway.

Marcus’s jaw tightened so hard I could see the muscle jump.

“You’re being unreasonable,” he said. “We’re trying to help you.”

“Help me out of my home,” I said.

“You’re sixty years old, Bob. How much longer can you maintain a place like this? The winters alone—”

“I was pulling people from burning buildings six months ago,” I said quietly. “Climbing ladders in −20 windchill. I think I can handle changing a furnace filter and clearing the roof after a snowfall.”

Jessica’s eyes shone, but it wasn’t just tears. There was something else there now—frustration, calculation, something cold she’d learned to wear like a blazer.

“It’s not just the house,” she said. “It’s Mom. She’s been confused. Forgetful. Last week, she couldn’t remember what day it was.”

“It was Saturday,” I said. “She knew exactly what day it was. She made a joke about it, remember? ‘Every day feels like Saturday now that you’re retired.’ You laughed.”

“She’s in denial,” Jessica said. “And so are you.”

Marcus stepped closer, trying to loom.

I didn’t move.

“We’ve been noticing signs for months,” he said. “The missed bills, the confusion, the memory problems. We’ve already scheduled a cognitive assessment. Friday.”

“Cancel it,” I said.

“We can’t,” Marcus said. “We won’t.” His voice hardened, the charm slipping. “You might not see it, but we do. And when that assessment comes back showing what we know it will show, we’ll have the legal authority to make decisions for both of you. For your own safety.”

There it was.

Not concern. Not love. Control.

That’s when I heard it again.

The crying.

Louder now that I was listening for it. Not from the deck, but from inside the house, muffled by walls and a closed door.

I pushed past them without another word and went inside.

The warmth of the house hit me, smelling like wood, lemon cleaner, and the faint, familiar scent of Margaret’s lavender lotion. A football game murmured on the muted TV in the living room. Through the sliding glass doors, I could still see the deck, empty now except for the abandoned champagne flutes.

The crying came from down the hall.

The master bedroom was at the end, the door closed, a strip of light glowing underneath like a line of caution tape.

“Margaret?” I called softly.

No answer. Just the sound of quiet, exhausted sobbing.

I opened the door.

My wife sat on the edge of the bed, still in the clothes she’d probably put on that morning—a soft blue sweater I liked, jeans, socks with little maple leaves on them. Her face was blotchy, streaked with tears. Her hair, usually brushed back neatly, hung loose around her shoulders.

When she looked up and saw me, I saw something in her eyes that made my chest tighten as if someone had wrapped a hose around it and pulled: fear.

“Bob,” she whispered. “You’re here. Why are you here?”

“Party got cancelled,” I said. I crossed the room in three strides. “What’s wrong, love? Why are you crying?”

She tried to stand and swayed. I caught her, the weight of her familiar in my arms.

“I don’t… I don’t know what’s happening,” she said, voice shaking. “Jessica gave me some papers to sign. She said they were power of attorney forms. For our protection. In case something happened. But I read them, Bob. I read them twice. They’re not what she said.” Her breath hitched. “She wants control of everything. The house, our accounts, our medical decisions. And when I said no, she got angry. She said I’m not capable of understanding anymore. That I’m losing my mind.”

She pressed her hands to her temples, fingers trembling.

“You’re not losing anything,” I said.

“How do you know?” she whispered. “What if I am? What if she’s right? I did forget what day it was last week. And I couldn’t remember where I put my car keys yesterday.”

“You made a joke about Saturday,” I reminded her gently. “You said every day felt like Saturday because we were retired. And your car keys were in your coat pocket. The coat you always hang on the back of that chair.”

I tipped her chin up so she had to look at me.

“Margaret, look at me,” I said. “There is nothing wrong with you that doesn’t come with getting older and having too many things on your mind. You misplace keys. So do I. I forget names and walk into rooms and can’t remember why I went in there. That doesn’t mean we’re incompetent.”

Her eyes filled again.

“Then why would Jessica say these things?” she asked.

That was the question.

I helped Margaret sit back down on the bed and pulled the comforter up around her shoulders. Her hands clutched at the fabric like it was a life raft.

On the nightstand, a mug sat half‑empty. The tea ring around the inside was cloudy, the way it gets when something has been dissolved in it.

The sight made my neck prickle.

I picked up the mug and sniffed. Chamomile and something bitter underneath.

“Did she give you anything?” I asked carefully. “For your nerves?”

“She said it was just tea,” Margaret said. “She said I was overreacting, and if I calmed down it would all make sense. I… I feel so tired, Bob. Like I’m underwater.”

I set the mug down as if it might explode.

I walked to the bedroom door, stepped out, and locked it from the inside. I could hear voices in the living room, sharper now. Jessica’s high and tight, Marcus’s lower, insistent.

“Stay here,” I told Margaret. “Lie down. Don’t drink anything else. Don’t sign anything. I need to handle something.”

“Bob, what are you going to do?” she asked.

“My job,” I said. “Same as always. Put out the fire.”

When I came back into the living room, Jessica and Marcus were huddled together near the kitchen island, whispering fiercely. Papers were spread out on the counter—forms with tabs, a black fountain pen laid neatly on top of a clipped stack. Jessica’s laptop glowed, an email open on the screen.

They broke apart when they saw me.

“She’s not signing anything,” I said.

Jessica’s mouth tightened.

“Dad, you’re not thinking clearly,” she said.

“I’m thinking perfectly clearly,” I said. “Clearer than I have in weeks, actually.”

I walked over to my armchair, the one I’d brought up from Thunder Bay when we retired. The old brown recliner was worn and familiar. I sank into it like I had a hundred times after long shifts, the leather creaking.

“Let me guess,” I said, folding my hands. “Marcus has financial problems.”

Marcus’s eyes flashed.

“That’s none of your business,” he snapped.

“Probably gambling,” I continued as if he hadn’t spoken. “Based on the tells I’m seeing. You’re restless, over‑explaining, pushing too hard on this project. You’re desperate. You looked at this property and saw dollar signs. So you concocted a scheme to have us declared incompetent, take control of our assets, and sell everything out from under us.”

Marcus’s face flushed red, then went strangely blank.

“That’s ridiculous,” he said.

“Is it?” I asked. “Because I just heard you planning exactly that on the deck. ‘Lake Superior Resort and Spa.’ Nice touch, by the way. Very brochure‑friendly.”

“We’re trying to save you from yourselves,” Jessica said. The shrill edge in her voice sharpened. “You’re too old to be living out here. Too old to manage your own affairs. It’s remote, it’s icy, you could fall on the steps and no one would know for days. If you can’t see that, then maybe the assessment is exactly what you need.”

Something inside me shifted. The last hope that this was all a misunderstanding, that I’d misheard, that Jessica had been venting or exaggerating—it cracked and fell away like charred ceiling.

“Get out,” I said.

Marcus blinked.

“Excuse me?” he asked.

“Get out of my house,” I said. “Both of you. Now.”

Marcus laughed. Actually laughed. The sound was high and a little too loud.

“We’re not going anywhere,” he said. “In fact, we’ve got some documents for you to sign, too. Transfer of property to a family trust. Durable power of attorney. All standard stuff for someone your age.”

“I’m sixty years old, Marcus,” I said. “Not senile.”

“That’s not what the doctor’s report says,” he said triumphantly.

He pulled a folder from his jacket and held it up like a winning lottery ticket.

“Memory issues, confusion, inappropriate decision‑making,” he read, tapping the page. “All signs of early cognitive decline. We’ve been documenting everything.”

“What doctor?” I asked. “Because I haven’t seen a doctor since my physical before retirement.”

“Dr. Raymond Chen,” he said. “Elder care specialist. We consulted with him last month about your decline.”

I stood up slowly.

“Let me see that,” I said.

He hesitated, then handed it over, confidence radiating off him.

I read through it. The letterhead looked legitimate—clinic name, Winnipeg address, professional crest. Detailed observations about my supposed confusion, my “wandering” at home, my “inability to manage finances.” Recommendations for immediate intervention.

It was convincing.

Except for one thing.

“This is dated October fifteenth,” I said.

“So?” Marcus said.

“So,” I said, looking up, “I was on a fishing trip with Tyler from October tenth to twentieth. In a boat on Lac des Mille Lacs, three hours north of here. I wasn’t even in the province. Try again.”

For a second, just a flicker, Marcus’s mask slipped. His eyes darted away and his mouth opened, searching for the next line in his script.

“Must be a typo,” he said finally, forcing a chuckle. “They make those all the time in medical offices.”

“Must be fraud,” I said.

I set the folder down on the coffee table with a soft thud.

“Last chance,” I said. “Leave now, or I call the police.”

“On what grounds?” Marcus demanded, spreading his hands. “Attempted theft? Fraud? Elder abuse? Take your pick?”

“Yes,” I said. “Exactly on those grounds.”

Jessica’s face crumpled.

“Dad, please,” she said. “We’re not trying to hurt you. We’re trying to help. Marcus and I… we’re in trouble. Real trouble. He owes money. A lot of money. And these people, they’re not nice people. We thought if we could just develop the property, flip it fast, we could pay them back and start over. Nobody has to get hurt.”

There it was.

The truth.

Or at least one layer of it.

“So you were going to steal your mother’s home,” I said quietly. “The home we built together. The place where you learned to swim, where you roasted marshmallows on that beach, where you caught your first lake trout off that dock.” My voice tightened. “You were going to drug your mother, forge documents, and sell it all to pay for your husband’s gambling debts.”

“We weren’t going to drug anyone,” Jessica protested weakly.

“I heard Margaret,” I said. “She’s barely coherent. What did you give her?”

Marcus shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

“Just something to help her relax,” he muttered. “She was getting hysterical about the papers.”

That was enough.

I pulled my phone out of my pocket.

“What are you doing?” Jessica asked, voice rising.

“Calling my son,” I said.

“Tyler’s not coming until Thursday,” she said quickly, almost panicked. “He has work.”

“He is now,” I said.

I dialed. Tyler picked up on the second ring.

“Dad?” he said, voice thick with sleep. “Everything okay?”

“Tyler, I need you at the lake house now,” I said. “And bring your laptop.”

“Dad, it’s almost eleven,” he said. I could hear Sarah murmur something in the background. “What’s going on?”

“Your sister and her husband are trying to steal the house,” I said. “I need your help.”

There was a pause. A long exhale.

“I’ll be there in two hours,” he said. “Don’t let them touch anything.”

I hung up.

Jessica was crying now. Big, messy tears. The kind that used to undo me when she was five and scraped her knee.

For a moment, a part of me—the part that still remembered braiding her hair before school picture day—wanted to wrap her up and tell her it would be okay.

Almost.

“Tyler’s bringing evidence,” I said instead. “Of everything you’ve done. And then we’re going to the police.”

“There’s no evidence,” Marcus said, but his voice wavered, the confidence leaking out of him.

“You sure about that?” I asked. “Because Tyler’s been worried about you two for months. He’s been doing some checking quietly.”

That was a bluff.

But I watched Marcus’s face and saw it land like a bucket of water on hot coals. He went pale.

“Dad, please,” Jessica begged. “If we don’t pay back this money, they’ll hurt Marcus. They’ve already made threats. His business partner… something happened to him. We’re scared.”

“Then you go to the police,” I said. “You don’t steal from your parents.”

“We tried,” she said. “They said without proof of the threats, there’s nothing they can do. And Marcus’s partner won’t talk. He’s too afraid.”

I looked at my daughter. Really looked.

When did she become this person? The girl who used to organize food drives at her high school now standing in my living room, justifying drugging her own mother.

“How much do you owe?” I asked.

“Two hundred thousand,” Marcus whispered.

The number hit the room like a dropped tool.

“What?” I said.

He ran a hand through his hair.

“I thought I could win it back,” he said. “I had a system at the casino. It was supposed to work. It did work for a while. Then it didn’t. And I kept trying to win it back. The people I borrowed from, they’re not… they’re not patient.”

“So you decided to solve your problem by destroying your wife’s parents,” I said.

“We were going to put you in a nice facility,” Jessica said quickly. “One of those retirement communities with activities and medical staff and outings to the mall. You’d have care.”

“And without asking us,” I cut in, “without our consent, you were going to have us declared incompetent and lock us away so you could take everything we’d worked for, turn it into a resort, and call it doing us a favor.”

Behind me, a soft sound made me turn.

Margaret stood in the doorway, one hand braced on the frame. She was pale but her eyes were clearer now, sharp, cutting through the room.

“Jessica,” she said, voice trembling, “tell me he’s wrong. Tell me you wouldn’t do that to us.”

Jessica’s shoulders hunched.

She couldn’t meet her mother’s eyes.

“Oh, baby,” Margaret whispered.

I heard something break in her tone that I had never heard in thirty‑five years of marriage. Not anger. Not even disappointment.

Something worse.

The next two hours crawled by.

I made coffee, strong and black, the way we drank it at the station on long winter nights. The bitter smell filled the kitchen, grounding me. Margaret sat at the kitchen table, her hands wrapped around a mug she barely drank from. Silent tears slid down her cheeks and disappeared into the collar of her sweater.

Jessica and Marcus huddled on the couch, whispering frantically, phones lighting up their faces. Every so often, one of them would look toward the front door like they were thinking about making a run for it.

Marcus tried once.

He stood, grabbed his coat from the hook, and took two steps toward the door.

I stepped in front of it.

“We’re not prisoners,” he said, chin jutting out.

“You’re not guests either,” I said. “You stay until Tyler gets here.”

“And then what?” His voice had a frantic edge now. “You’ll have us arrested? Jessica is your daughter.”

“Jessica drugged her mother and tried to steal our home,” I said. “That changes things.”

Outside, the wind picked up, rattling the branches against the windows. Lake Superior’s low roar was a constant undertone.

Headlights finally swept through the front windows at 1:30 a.m. Gravel crunched. A car door slammed. Then another.

Tyler came through the door like a storm—coat unzipped, hair tousled, laptop bag slung over his shoulder. Sarah was right behind him, hair pulled back in a messy bun, eyes clear and alert.

“Dad?” Tyler crossed the room and hugged me hard, the way you hug someone when you don’t know what you’re walking into. “Are you okay? Is Mom okay?”

“We’re handling it,” I said.

I nodded toward the couch.

“They’re still here.”

Tyler turned.

He looked at Jessica for a long, silent moment. Something passed between them—years of shared bedrooms, road trips, Christmas mornings—turning to something cold and brittle.

“Jess, what the heck?” he said finally.

“Stay out of this, Tyler,” Jessica snapped.

“Stay out of you stealing Mom and Dad’s house?” he said. “I don’t think so.”

He walked to the coffee table, set his laptop down, and opened it. The glow from the screen lit his face, all hard lines and focus now. I had seen that look on him once before, when he sat at our kitchen table in college, studying for finals with a stack of textbooks and a pot of coffee.

“I’ve been tracking you two for three months,” he said. “Ever since I heard about Marcus’s ‘business troubles.’ Want to see what I found?”

Marcus stood up so fast the couch rocked.

“You had no right—” he started.

“Sit down,” Tyler said.

His voice could have cut glass.

Marcus sat.

“Casino records,” Tyler said, fingers flying over the keyboard. “Two hundred forty‑seven thousand dollars in losses over eighteen months.”

He turned the laptop slightly so we could see.

Rows of transactions glowed on the screen—casino names, dates, amounts that made my stomach twist.

“Money borrowed from known loan sharks and high‑interest lenders,” Tyler continued. “Threats documented in your email. Three previous attempts to borrow from family, all declined.”

He clicked again.

“And this,” he said.

He turned the laptop fully toward Jessica and Marcus.

“The fake Dr. Chen, who is actually Dr. Raymond Chen, chiropractor practicing in Winnipeg. I called his office. He’s never heard of either of you and is very interested in who’s using his letterhead for fraud.”

Jessica made a sound like a wounded animal.

“And there’s more,” Tyler said, relentless now. “The memory clinic you booked for Mom—doesn’t exist. The elder care attorney Marcus mentioned? He’s a hired actor. Works out of Toronto. Specializes in corporate video production. I’ve got his contact info and the payment from Marcus’s account to his agency.”

He flipped to another file.

“The ‘incident reports’ about Mom’s confusion and missed bills? I pulled the actual utility records and bank statements. Bills have been paid on time for three years straight. No late fees. No shut‑off notices.”

He opened a PDF.

“The power of attorney documents you tried to push on Mom? I had a real lawyer in Thunder Bay look at them. They’re not just aggressive. They’re illegal in Ontario. Anyone signing them would be signing away all their rights with no recourse.”

“How did you get all this?” Marcus demanded, his voice cracking.

“I’m a database analyst for the provincial government,” Tyler said. “I know how to find information.”

He closed the laptop with a soft, final click.

“And I know how to package it for the police.”

Jessica wiped at her face.

“We were desperate,” she whispered.

“You were criminal,” Tyler said. “There’s a difference. If Marcus was in danger, there were a dozen legal ways to handle it. Debt consolidation. Bankruptcy. Downsizing your own life. You chose this instead.”

“Tyler, please,” Jessica said, standing now, reaching toward him like she had when they were kids and she needed help opening a jar. “He’s my husband. I love him. I couldn’t let anything happen to him.”

“So you were going to let something happen to Mom and Dad instead?” Tyler asked.

The question hung in the air.

Silence settled over the living room. The kind of silence that settles over a fire scene after the flames are out and all that’s left is wet ash and ruined walls.

I stood up.

“I’m calling the police,” I said.

“Wait,” Marcus said, jumping to his feet, hands up. “Just wait. What if we leave right now? We’ll disappear. Go somewhere far away. You’ll never hear from us again.”

“And the people you owe?” I asked.

“I’ll figure something out,” he said quickly. “They’ll come looking.”

“Then I’ll deal with it,” he said. “Just don’t call the police. Please. Jessica will lose her real estate license. She’ll have a criminal record. Her life will be over.”

“She should have thought of that before she drugged my wife,” I said.

Margaret’s voice, quiet but steady, cut through.

“What did you give me?” she asked.

Jessica looked at the floor.

“Sleeping pills,” she whispered. “Ground up in your tea. You were so upset about the papers, you wouldn’t listen. Marcus said if you just slept for a while we could… we could—”

“”We could forge my signature,” Margaret finished.

Jessica sobbed.

“We wouldn’t have had to,” she said. “If you’d just listened to reason.”

Margaret straightened.

For the first time that night, I saw steel return to her spine.

“Reason would have been talking to us,” she said. “Reason would have been saying, ‘Mom, Dad, we’re in trouble. We need help.’ Not drugging me and stealing our home.” Her voice shook, but it didn’t break. “You’re my daughter. I would have done anything to help you. Anything. But you didn’t trust me enough to even ask.”

Jessica dissolved into tears. Real ones, not the controlled, convenient tears she could switch on during a negotiation. These were messy, raw, ripping through her shoulders.

But something in me had shifted too far to go back.

I picked up my phone and dialed 911.

“OPP dispatch,” a calm voice answered after two rings.

“My name is Robert Harrison,” I said. “I’m at a lake house off Highway 17 outside Nipigon. I need to report an attempted theft and elder abuse. There’s fraud. Drugging. Fake medical documents. I have evidence.”

Marcus lunged for me.

Tyler moved faster.

He intercepted his brother‑in‑law, shoving him back onto the couch with a force I didn’t know he had. Sarah, eyes wide but hands steady, pulled out her own phone and started recording.

“Don’t move,” Tyler said. “Sarah’s got video now. Everything you do is evidence.”

Outside, the night deepened. Inside, the clock on the wall ticked too loud.

The OPP officer arrived forty‑five minutes later. The Ontario Provincial Police served this area out of Nipigon, the small town up the highway where we’d always stopped for gas and coffee.

Her name was Officer Patricia Devo. Mid‑forties. Dark hair pulled back in a tight bun. No‑nonsense face. The kind of person who had seen every kind of trouble northern Ontario could throw at her and then some.

She stepped into our living room, boots squeaking on the mat, eyes taking everything in with one sweep—the scattered papers, the laptops, the drained champagne bottle on the counter.

“Who’s Robert Harrison?” she asked.

“I am,” I said.

“All right, Mr. Harrison,” she said. “Let’s start with you.”

She took statements from all of us separately. She listened as Margaret told her about the tea and the papers. She watched the video Sarah had taken, scrolled through Tyler’s files, examined the fake documents with a practiced eye. She made calls to confirm what she could on the spot.

By four in the morning, Marcus sat on the edge of the couch, hands clasped, eyes fixed on some spot on the floor that only he could see.

“Mr. Chen,” Officer Devo said, standing in front of him, “you’re under arrest for fraud, attempted theft, and administering a noxious substance. You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used in court…”

The words rolled out, formal and steady.

Marcus looked at Jessica then, real panic on his face.

Jessica wasn’t arrested that night. Not yet. But when Officer Devo turned to her, her tone left no room for comfort.

“You’re not off the hook, Miss Chen,” she said. “Your involvement in this is serious. There will be a full investigation. I strongly suggest you get a lawyer.”

They took Marcus away. The patrol car’s red and blue lights flashed silently across the trunk of our pine tree as it backed down the drive and turned toward the highway.

Jessica sat at our kitchen table alone, shoulders shaking.

“You should go,” Margaret said quietly.

“Mom, I’m so sorry,” Jessica sobbed. “I’m so, so sorry. I don’t know what I was thinking. I just—”

“I know,” Margaret said. “But you still need to go.”

Jessica looked at me then, eyes searching for something—absolution, maybe, or the father who’d once fixed her broken bicycle in the driveway.

I didn’t have that in me.

She left.

We heard her car start, heard the gravel crunch as she drove away into the November darkness, tail lights disappearing between the trees.

Tyler stayed. He and Sarah made up the guest room with the practiced efficiency of two people who had done emergency sleepovers with kids before. Then the four of us—me, Margaret, Tyler, and Sarah—sat in the dimming light of the living room and watched the sun start to lift out of Lake Superior.

It turned the thin skin of ice along the shore into sheets of pink and gold. The world looked calm. Our insides did not.

“I never wanted this,” I said finally, fingers wrapped around a mug of coffee gone cold. “I just wanted to grow old in peace.”

“I know, Dad,” Tyler said. He put his hand on my shoulder, solid and warm. “But we’ll get through it. We’ll protect what you built.”

The next weeks blurred.

Paperwork. Police calls. Meetings with lawyers in offices that all smelled faintly of stale coffee and printer ink. I learned more about words like “power of attorney” and “capacity” and “fraudulent misrepresentation” than I ever wanted to know.

Marcus was formally charged with fraud, identity theft, attempted theft, and administering a noxious substance. He pled not guilty at first. Then the evidence kept stacking up—emails, bank transfers, the actor from Toronto giving a statement about the “training video” he’d been hired to record, the real Dr. Chen from Winnipeg outraged that his name had been dragged into it.

Jessica wasn’t charged with the same criminal counts, but the Ontario Real Estate Association opened an investigation. Her license was immediately suspended pending the outcome. We heard through Tyler that she’d moved out of the townhouse she shared with Marcus and into a small basement apartment closer to downtown Thunder Bay.

The people Marcus owed money to didn’t show up at our door like he’d implied. Tyler dug deeper—using his access to public records, his researcher’s patience—and found that most of the debt was to a legitimate casino, not to shadowy criminals in back alleys. There were calls from collection agencies, letters threatening lawsuits, wage garnishment, bankruptcy.

Scary.

But not the violence he’d painted to manipulate Jessica.

Maybe that was the cruelest part. She’d set fire to her family for a story that wasn’t even fully true.

The trial was in January.

By then, winter had settled in full. The highway to Thunder Bay was a corridor of snowbanks and salt spray. We drove in for each court date, parking in the same spot in the municipal lot, walking carefully over icy sidewalks to the courthouse.

Inside, everything was beige—walls, floors, file folders. The only color came from people’s coats and the Canadian flags behind the judge’s bench.

I testified.

I told the story from the beginning: the drive, the laughter on the deck, the words I heard, the mug of tea by Margaret’s bed. I saw jurors shift in their seats when I described hearing my daughter say we “wouldn’t even know the difference” once we were moved into a facility.

Margaret testified.

Her hands shook as she held the Bible, but her voice was clear as she talked about the papers she had refused to sign, the moment she realized her own daughter was trying to take away her choices.

Tyler presented his evidence like the professional he was. Organized. Precise. Every file labeled. Every transaction traced.

The prosecutor was thorough. Marcus’s lawyer did what he could, but against the sheer volume of documentation, his arguments sounded thin.

Email chains. Fake letters. Payments to the actor. Casino transactions. Draft contracts with developers. It was like watching someone trying to explain away smoke while the building burned down behind him.

Marcus was found guilty on all major counts.

The judge—a woman in her fifties with tired eyes—was harsh.

She spoke about the particular vulnerability of older adults, about the trust placed in family, about the seriousness of using legal tools like power of attorney as weapons instead of protections.

Then she sentenced Marcus to five years in federal prison, with no parole eligibility for at least three.

Jessica didn’t go to prison, but her consequences were real and public. Her real estate license was revoked permanently. Her name appeared in small black letters in the “disciplinary actions” section of the real estate board newsletter. She filed for divorce less than a month after the sentencing.

At the prosecutor’s request, as part of a restorative justice component, Jessica agreed to make a public apology.

It happened at the Thunder Bay town hall in February, during a community meeting about elder abuse prevention. There were chairs set up in neat rows, pamphlets on tables, a slide presentation about common scams targeting seniors.

Margaret and I sat in the front row. Tyler and Sarah sat behind us. I could feel my wife’s hand in mine, her fingers icy despite the heated room.

Jessica stood at the podium, small under the bright fluorescent lights.

“My name is Jessica Harrison Chen,” she began, her voice trembling enough that the microphone picked it up. “And six months ago, I drugged my mother and attempted to steal my parents’ home to pay my husband’s gambling debts.”

The room went very still.

You could hear the hum of the projector.

“I told myself I was helping them,” she continued. “That they were too old, too confused, that they needed me to make decisions for them. I used words like ‘safety’ and ‘care’ and ‘protection’ to justify what I was doing. But the truth is, I needed their home. I needed their money. And instead of asking for help like a decent person, I chose to betray them.”

Her voice cracked.

“My father is sixty years old,” she said. “He served this community for thirty‑two years as a firefighter and chief. He’s pulled people from burning buildings, saved lives, missed Christmas mornings and school plays because someone’s house was burning down. And I treated him like he was incompetent.” She swallowed hard. “Like he was in my way.”

She took a shaky breath.

“My mother taught second grade for twenty‑eight years,” she said. “She taught kids to read, tied shoelaces, went to parent‑teacher nights. She shaped hundreds of children’s lives. And I drugged her because she wouldn’t sign papers that would let me take everything she and my father worked for.”

Tears streamed down her face, streaking her mascara.

“I can’t undo what I did,” she said. “I can’t take back the betrayal. But I can stand here and tell you that elder abuse doesn’t just happen to strangers on the news. It happens in families. It happens when people get desperate and start seeing the people who love them as obstacles instead of human beings. And it destroys everything.”

She looked directly at us.

“Mom, Dad,” she said. “I know you can’t forgive me. I know I broke something that can’t be fixed. I just want you to know that I see what I did. I understand what I destroyed. And I will spend the rest of my life trying to be better than the person I was that night.”

She stepped down from the podium.

There was no applause.

Just silence. Heavy, thoughtful, judgmental silence.

We didn’t speak to her afterward. We walked past the coffee urn and the pamphlets and the people murmuring to each other and went out into the cold February air. Our breath fogged in front of us as we walked to the car. The snowbanks along the street were gray at the edges, the way they always are after months of winter.

That night, back at our small apartment in Thunder Bay—the place we’d moved into for the winter while the lake house sat empty and dark—we sat at the kitchen table while the baseboard heaters ticked.

Margaret cried.

Not for Jessica’s public shame.

For what we’d lost.

“She was our daughter,” Margaret whispered. “How did we not see it coming?”

“We trusted her,” I said. “That’s not a failure. That’s what parents do.”

“Should we forgive her?” Margaret asked, her eyes searching my face.

I stared at the little magnet on our fridge—a cartoon moose wearing a Mountie hat that Jessica had bought as a joke when she was fifteen.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe someday. But not today.”

Tyler and Sarah started coming for dinner twice a week. Their kids, eight and six, turned our quiet apartment into something that felt alive again. Lego bricks underfoot, homework spread across the table, the constant chatter about school and hockey practice and who had the best goalie mask.

We taught them to play cards. We read them stories. We started talking about summer at the lake house as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

In March, a letter arrived from Jessica.

It was in her handwriting, the same looping script she’d used on the place cards she made for Thanksgiving years ago. My name and Margaret’s on the front. No return address.

I held it for a long time, feeling the weight of it, the roughness of the envelope under my thumb.

“Aren’t you going to open it?” Margaret asked.

I looked at my wife.

She’d aged in the months since that November night. We both had. There were deeper lines around her mouth, new strands of gray in her hair. But she was still my Margaret—the woman who’d stood in a too‑hot banquet hall thirty‑five years ago and promised she’d walk beside me through everything.

“No,” I said finally. “Not today. Maybe not ever.”

I set the envelope in the top drawer of the buffet. Closed it.

That weekend, Tyler drove us back up to the lake house to start opening it for spring.

The highway was lined with dirty snow, the piles receding to reveal gravel and sand. Puddles shone like bits of sky in the ditches. The air had that sharp, hopeful smell it gets when winter loosens its grip just a little.

When we pulled into the driveway, the house looked small against the massive backdrop of Lake Superior. The ice along the shore was breaking up, chunks drifting and grinding together. The deck was dusted with old snow and pine needles.

We walked out onto the boards I’d laid myself.

The deck where I’d heard my daughter plan to destroy us.

“We could sell,” Margaret said quietly, wrapping her arms around herself. “Start fresh somewhere else.”

I looked at the house. At the windows I’d installed, the doorframe I’d sanded, the garden beds along the side that waited for her lupines and black‑eyed Susans.

“No,” I said.

I put my arm around her, pulled her against my side.

“We built this with love and work and time,” I said. “No one takes that from us. Not Jessica. Not Marcus. No one.”

Tyler came out with the kids. They were bundled in spring jackets and hats, cheeks pink from the wind.

“Can we go down to the beach, Grandpa?” my granddaughter asked, practically bouncing.

“Yes, you can,” I said. “Stay where I can see you.”

They ran down the worn path, boots slipping a little on damp leaves, laughter carried back to us on the cold wind.

Tyler stayed on the deck with us.

“Jessica’s been trying to reach me,” he said after a moment. “Text, email. She wants to talk.”

“That’s your choice,” I told him. “She’s your sister. I won’t tell you what to do.”

“What would you do?” he asked.

I watched my grandchildren at the water’s edge, their bright jackets tiny against the spread of the lake. The sun hit the waves, turning the surface into thousands of shards of light.

“I don’t know, son,” I said. “I honestly don’t know. Maybe someday I’ll be able to forgive her. Maybe I’ll be able to see her as my daughter again instead of the person who tried to destroy us. But right now? Right now, I just want to enjoy what I’ve got. This house. Your mother. You and your family. That’s enough.”

Margaret leaned her head against my shoulder.

“We survived,” she said.

“We did,” I said.

“Will we be okay?” she asked.

I looked at the house behind us. The roofline against the sky. The garden Margaret would plant in May. The dock where I’d teach my grandchildren to bait hooks and untangle fishing lines. The bedroom where we’d watch storms roll in over the lake.

“Yeah,” I said softly. “We’ll be okay.”

Thanksgiving came around again.

Nearly a year since that November night.

Tyler and Sarah and the kids came up for the whole weekend. The house filled with the smells that meant holiday in our family: turkey in the oven, sage and onion stuffing, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pie cooling on the counter. The kids argued good‑naturedly over who got to whip the cream.

We watched the Macy’s parade on American TV out of Minnesota, then switched to a football game. Snowflakes drifted lazily past the windows, not yet sticking.

After dinner, while the kids played board games at the dining table—arguing about the rules of Monopoly as if Parliament depended on it—Tyler came over to the couch where I sat.

“Jessica sent this,” he said, holding out his phone.

On the screen was a photo.

Jessica, thinner, her hair pulled back in a simple ponytail. Her face looked older, the angles sharper, but her eyes were clear. She wore a plain T‑shirt and apron, standing behind the counter at what looked like a coffee shop. A chalkboard menu hung behind her. There was a smudge of foam on her sleeve.

The caption under the photo read: “Nine months sober. Therapy three times a week. Working double shifts. Living with the consequences of my choices. I hope you’re all well.”

“Are you going to respond?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Tyler said. “Should I?”

Margaret came over, wiping her hands on a dish towel. She leaned over to see the screen. For a moment, her face went very still.

Pain. Grief. And maybe—just maybe—the faintest hint of something else.

“That’s between you and your sister,” she said finally. “But Tyler, don’t let what she did poison your relationship with her forever. She made terrible choices. She hurt us deeply. But she’s still your sister, and maybe someday she’ll be someone we can know again.”

“Not today, though,” I said.

“No,” Margaret said, squeezing my hand. “Not today.”

That night, after everyone had gone to bed and the house was finally quiet except for the ticking of the baseboard heaters and the soft rush of the lake, I stepped out onto the deck one more time.

The November air was cold, just like it had been a year before, but it felt different somehow. Sharper. Cleaner.

The stars were out, hard and bright, scattered across the sky. Their reflections trembled in the dark water below. Somewhere far across the lake, a faint glow marked the American shore.

I stood at the railing and breathed.

I’d learned something that night when I came home early.

I’d learned that the people you love most can hurt you the deepest. That trust isn’t some abstract thing; it’s a living bridge you walk across together every day. And if one person sets fire to their side of it, there’s no guarantee it’ll hold.

I’d learned that age doesn’t make you vulnerable.

Trusting the wrong people does.

But I’d also learned something else.

That you can survive betrayal.

That you can set boundaries so firm they feel like walls and still love someone from a distance. That forgiveness and reconciliation are not the same thing—and that you have the right to choose one without the other.

That the life you build with your own hands, board by board and day by day, can’t be taken unless you sign it away.

The lake stretched out before me, dark and endless, the same as it had been the night Jessica plotted against us and the same as it had been the first afternoon we stood here with a realtor and a shaky mortgage approval.

Behind me, the house glowed warm through the windows. Shadows moved—Margaret turning down the bed, Tyler checking the locks, the kids already sprawled in sleep across their blankets.

Margaret came out and wrapped a blanket around both of us, pressing her cheek to my shoulder.

“What are you thinking about?” she asked.

“How lucky I am,” I said. “Despite everything.”

She kissed my cheek.

“Me too,” she said.

We stood there for a while, watching the stars reflect on the water. For the first time in a year, peace settled over me, not as a dramatic wave but as a quiet, steady certainty.

The house was still ours.

The life we’d built was still ours.

And whatever Jessica became from here on out—whatever path she walked, whatever work she did to rebuild herself—it would be hers alone.

We had protected what mattered.

We had survived.

And sometimes, that is not just enough.

Sometimes, it’s everything.

News

My whole family went to the beach together, and to me they said, “It’s better if you stay home and take care of the work.” I didn’t say anything. When they came back, my room was empty.

They told me to stay behind and work while they took Emily and Jake to the beach. Dad was already…

For five years, I silently worked extra jobs, saving every penny to pay for my husband’s medical tuition, hoping that the day he wore the white coat would be a source of pride for both of us. But right when he graduated, instead of thanking me, he placed an envelope in front of me and said, “You are no longer worthy of me.”

After the divorce, Amara vanished from his life without a forwarding address. One year later, Dr. Keon Sterling—now a rising…

I am Marianne Kepler, a 59-year-old widow who has quietly supported my daughter financially for many years. On my birthday, when I asked her for help so I could see a doctor, she looked straight at me and said, ‘Stop bringing up money. It’s annoying.’ I just smiled and replied, ‘All right.’

My name is Marianne Kepler. I am fifty-nine years old, a widow tucked into a small blue house on a…

I went to a warm, peaceful, love-filled Christmas lunch in Los Angeles, but my son-in-law’s mother was sitting in my seat. ‘Priorities,’ she said with a smile. My daughter smiled and nodded. Silence fell over the room. They served her first. I stood up and left. I wondered since when my presence no longer mattered. And why no one stood up for me. What happened afterward made them run after me. They had underestimated me once again.

The smell of roasting thyme and sage should have been a comfort. It should have meant family, warmth, and the…

My mother led my three sisters into the house I had just bought; each of them chose a room for herself, and the biggest room was my mother’s. I stayed silent. The next morning, I changed all the locks.

My name is Chloe Fox. Right now, I’m sitting in a cheap motel room just off Interstate 95, the kind…

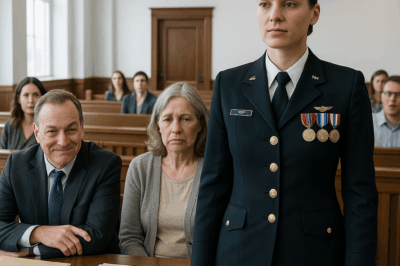

I Showed Up in Uniform — What the Judge Said Made the Entire Court Go Silent

The August heat pressed against the windows of Portsmouth Family Court like an unwanted guest, thick and insistent. I stood…

End of content

No more pages to load