I should’ve known something was wrong the second my parents called.

Three years of silence—no birthday texts, no Christmas cards—and suddenly they were begging me to come home for a weekend to house-sit. Their voices on speakerphone had sounded too sweet, too careful, like people performing normal.

I told myself they were trying to reconnect. I wanted to believe that. So I drove the three hours back to the cul-de-sac where I grew up, past the same perfect lawns and identical mailboxes, past the house that still looked frozen in time.

Inside, everything was exactly as I remembered it: the faint smell of lemon cleaner, the same floral couch, the framed family photos that pretended we’d been happy. It felt like walking into a museum of my own childhood.

They’d left in a hurry for some “conference” in the city, Mom’s handwriting scrawled on a note by the fridge:

Keep the plants watered. Don’t go into the basement—still asbestos down there.

I’d always believed that. The basement had been off-limits my entire life. Dad used to say the air down there would ruin your lungs. So I stayed upstairs, cooked frozen dinners, watched the muted glow of old reruns on TV.

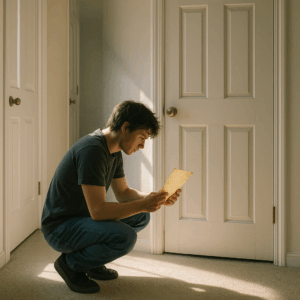

On the third night, I noticed it—a small piece of paper half-tucked under the basement door. It shouldn’t have been there. The house didn’t get drafts, and no one had been inside but me.

At first I tried to ignore it. But the longer I stared, the more it pulled at me, like a whisper I couldn’t unhear. I crouched down and slid it free.

It was a piece of torn notebook paper, yellowed around the edges but smeared with fresh ink. In a shaky, childlike scrawl, it said:

“You’re invited to Sherry’s birthday party. Today. Downstairs.”

The letters bled slightly, the way ink does when it’s still wet. My chest went cold.

Sherry. My best friend from high school. Missing for three years.

I read it again, over and over, trying to make sense of it. The handwriting looked familiar—like hers—but that was impossible. She was gone. The whole town had searched for her. Even my parents had joined the search parties, pinning missing-person flyers to telephone poles.

My hands were shaking as I called Roger, the neighbor who still lived a few houses down. He’d been our childhood partner in every dumb adventure—tree forts, haunted houses, the works. If I was losing my mind, at least someone else could witness it.

Roger showed up fifteen minutes later, out of breath and grinning like this was just another prank. “Wow,” he said when I handed him the note. “That’s seriously messed up. Where’d you find it?”

“Sticking out of the basement door.”

He squinted at the door like it might talk back. “You sure this isn’t one of your parents’ weird jokes?”

I shook my head.

Roger’s grin faded. “Then maybe we should take a look.”

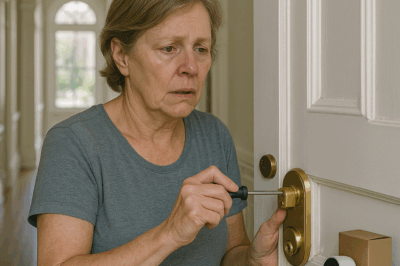

Before I could protest, he was already crouched at the door with the pocket multitool he carried everywhere. “Don’t,” I hissed. “They said there’s asbestos—”

“Come on, that’s probably bull. Look, if Sherry’s name is down there, don’t you want to know why?”

The lock clicked open. The sound was small but final.

The door swung inward with a sigh of cold air.

The basement looked ordinary at first—concrete floor, washer and dryer, dusty holiday decorations stacked in plastic bins. But at the back, one section of paneling looked wrong. The color didn’t match the rest of the wall.

Roger walked toward it and pressed his palm flat. The panel shifted, then swung open like a hidden door in a movie. Behind it was another door, heavier, with a thick padlock bolted from the outside.

“I don’t suppose you can pick this one too,” I said, but my voice sounded far away.

He grinned nervously, found my dad’s toolbox, and grabbed a hammer. Two blows and the lock split open.

The door creaked.

The air that spilled out was warm, heavy, and stale. I caught a whiff of something sweet and rotten underneath.

Then I saw her.

At first I thought she was a ghost—pale skin, hair hanging down to her waist, eyes wide and terrified. Her ankle was raw and bleeding, a broken chain dangling from it. She raised a metal pipe above her head and screamed, “Stay back! I’m warning you!”

“Sherry?” Roger’s voice cracked.

Recognition flashed across her face. The pipe clattered to the floor. “You’re not them,” she whispered, and then she collapsed into sobs. “Please—please help me.”

We got her upstairs, half-carrying, half-dragging. Her skin was ice cold. Roger found a first-aid kit while I tried to keep my hands from shaking.

“How long have I been gone?” she asked.

“Three years,” I said.

She nodded slowly, like she’d already guessed. Then she looked up at me with hollow eyes. “Your parents told me you’d sent me a gift from college. They said you wanted me to come by for tea.” Her voice cracked. “They made cookies. I remember the taste—sweet, then… blurry. When I woke up, I was chained. They told me nobody would come for me. That no one even missed me.”

The words barely made sense. I wanted to stop listening, but she kept going—how they taunted her with news articles about the search, how they laughed about my “poor gullible friend.”

“I broke the chain this morning,” she said. “I was going to lure them down there with that note. End it myself.”

The front door slammed before I could respond.

“Honey, we’re home early!” Mom’s voice floated up the stairs.

The sound froze me.

Sherry’s grip tightened on my arm. “I’m sorry,” she whispered. “But I’m ending this.”

The sound of my mother’s heels on the hardwood was unmistakable—sharp, rhythmic, getting closer.

For a second, I stood there like a child caught doing something wrong. Roger hovered by the door, phone in hand, his thumb already over 9-1-1.

Sherry moved faster than either of us. She grabbed a pair of scissors from my desk, flipped them in her hand like a weapon, and pressed her back against the wall beside the door. Her breathing was quick and shallow, the sound of an animal cornered.

The stairs creaked.

“Oh, honey,” Mom called up, cheerful as ever. “We canceled the conference. Thought we’d surprise you!”

Every muscle in my body went rigid. I could already hear Dad’s heavier footsteps behind her, his low voice saying something about the luggage.

Sherry’s eyes locked on mine. “They can’t get away again,” she whispered. “Not this time.”

The door opened.

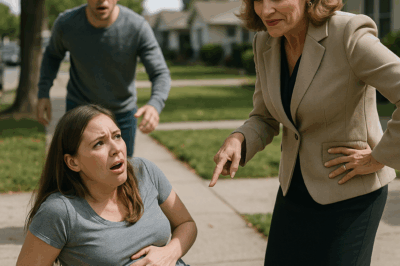

My parents froze in the doorway, taking in the scene: me standing rigid by the bed, Roger with his phone raised, and Sherry, barefoot, pale, and shaking, holding the scissors like she was born with them.

For one long, suspended second, no one breathed.

Then Mom screamed.

Dad lunged forward, reaching for the scissors. Sherry slashed instinctively, catching his palm. The cut was shallow but bloody enough to paint the carpet.

Roger shouted, “I’m calling 9-1-1 right now!” His voice cracked.

Mom’s performance began instantly. She stumbled back, clutching her chest. “Oh my God, she’s having another episode! She’s dangerous!”

Her voice was trembling, her eyes wide with practiced fear. I’d heard her use that tone on neighbors before—honeyed panic, perfectly believable.

“Don’t listen,” Sherry snarled, her voice shaking but fierce. “They’re lying.”

Dad backed toward the hall, cradling his hand. His eyes darted from the scissors to me, calculating. “You need to help us restrain her,” he said. “She’s sick, honey. You don’t understand.”

I couldn’t move. Couldn’t speak. Everything about that moment felt unreal—the familiar walls, the smell of Mom’s perfume mixing with blood and sweat and fear.

Mom reached for me. “Sweetheart, she broke in. She’s confused. She’s not well—”

“Stop!” My own voice came out hoarse. “Just stop talking.”

She froze mid-step, eyes wide.

Sherry’s hand trembled on the scissors, but her voice stayed steady. “If they touch me again, I’ll fight.”

Roger pressed the phone to his ear. “The police are coming,” he said. “Two minutes.”

Dad tried to edge toward the stairs. Roger blocked him. The air felt thick, suffocating. I could hear my own heartbeat pounding in my ears.

Mom’s face changed then. The panic melted into something colder, sharper. She looked at me with flat eyes and said, “If you do this, if you side with her, we’ll all go to prison. Is that what you want?”

Her voice dropped to a whisper meant only for me. “You’re our daughter. Back us up.”

I took a step back. Her hand reached for my wrist, nails digging in hard enough to leave marks. The look on her face wasn’t fear anymore—it was fury. Pure, naked rage that I’d never seen before.

Then the sirens wailed outside.

The flashing red and blue lights painted the walls before I even heard the door open downstairs. Four officers rushed in, weapons drawn but controlled, shouting commands. “Hands where we can see them! Everyone separate!”

Mom started sobbing again, instantly back to the act. “Thank God you’re here! She attacked us! She broke in!”

Two officers moved to her, their expressions unreadable. Another knelt beside Dad, who held out his bleeding hand like proof. The fourth officer—a woman with short brown hair—motioned me toward the hallway.

“Ma’am, come with me.”

Her voice was calm, professional. I followed her downstairs on autopilot. Behind me, I heard Sherry trying to explain, her voice breaking.

“They kidnapped me. They kept me in the basement for three years. Please—you have to believe me.”

The officer sat me on the couch, her notebook already open. “Start from the beginning,” she said.

So I told her. About the note. The basement. The false wall. The chain. My parents coming home. My words came out flat and mechanical, like I was reading a list.

The officer’s pen scratched across the page. Her face didn’t change, but her eyes flicked toward the basement door every few seconds.

“Ma’am,” one of the male officers called from the stairs, “you’re gonna want to see this.”

She stood and walked off. A few seconds later, I heard her whistle low.

When she came back, her face was pale. “We’re calling forensics and a detective,” she said quietly.

By the time the detective arrived—Heather Hansen, mid-forties, sharp-eyed—the house was crawling with uniforms and yellow tape. They took photos of everything, bagged the broken padlock, measured the chain. The whole time, Mom never stopped crying, and Dad never stopped watching me.

At one point, when no one was looking, he leaned toward me and whispered, “Think carefully about what you’re doing. Once this starts, there’s no going back.”

I turned away from him.

Detective Hansen spent a long time talking to Sherry in the ambulance outside. When she came back in, her face was set in the kind of grim determination I recognized from people who’d seen too much.

“They’re both coming with us tonight,” she told one of the officers. “This isn’t just assault. This is abduction.”

Mom wailed as they cuffed her. “This is a mistake! You don’t understand! We were helping her!”

Dad didn’t say a word. Just stared at me as they led him out, blood still dried on his palm, his eyes hollow and unreadable.

Outside, the flashbulbs from crime-scene cameras lit up the night like lightning. The neighborhood was awake, watching from their lawns, whispering.

Roger sat across the street on his parents’ porch, his face ghost-white. When our eyes met, he mouthed, You okay?

I didn’t answer.

Because no, I wasn’t okay. None of it was okay.

My parents were being taken away in handcuffs for torturing my best friend under our own house, and I’d had no idea.

And even as the police cars pulled out of the driveway and the sirens faded down the block, I knew this wasn’t the end.

This was only the beginning of finding out who my parents really were.

The flashing lights finally died down around midnight, but the noise inside my head didn’t.

Even after they’d taken my parents away, the house still buzzed with movement — officers talking into radios, cameras flashing, evidence bags being sealed. Every corner of my childhood home had turned into a crime scene.

I sat on the front porch wrapped in a blanket someone had handed me, staring at the police tape fluttering in the warm night breeze. The smell of antiseptic and blood clung to the air. Sherry was in the back of an ambulance, refusing to go anywhere until she knew my parents wouldn’t be released.

Detective Hansen crouched down in front of me. Her voice was calm, almost gentle. “We need a full statement from you tonight if you’re up for it.”

I nodded because saying no felt impossible.

They brought me inside — not to my bedroom, not to the couch I’d grown up watching cartoons on, but to a folding chair in the living room that faced the camera. The walls felt smaller now. I couldn’t stop looking at the spot on the carpet where Dad’s blood had dripped.

“Start from the beginning,” Hansen said.

So I told her everything again, this time for the record. How my parents had called me out of nowhere. How the basement door had been locked my whole life. How Roger and I found the note, and then the secret room, and then Sherry.

She didn’t interrupt. Just scribbled notes, nodding slightly every few minutes.

When I got to the part about the hidden door, she paused. “Had your parents ever mentioned doing renovations?”

“Not really,” I said. “Dad said the basement was unsafe. Asbestos or something.”

Hansen’s pen hovered. “And you never questioned that?”

Her tone wasn’t judgmental, but it still made me feel like an idiot. “No,” I said quietly. “They were my parents.”

That earned me a look — not pity exactly, but something close. “Okay,” she said. “That’s normal. Kids believe what they’re told.”

Normal.

Nothing about this night felt normal.

She asked about my childhood — the basement, the noise machines my parents ran constantly, the way they never let me bring friends over. As I spoke, the memories rearranged themselves, taking on new meaning. Every locked door, every excuse about privacy, every late-night trip to the basement I wasn’t allowed to question.

By the time I finished, my throat hurt from talking.

Hansen set her pen down. “You did the right thing tonight,” she said. “You saved her life.”

The words landed like a punch. Saved her. I hadn’t saved anyone. I’d just stumbled into the truth years too late.

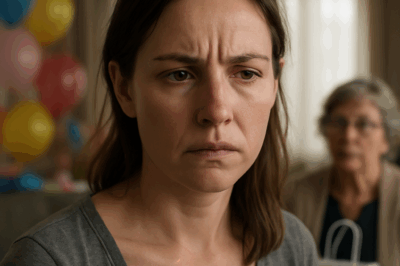

Outside, the paramedics were finally convincing Sherry to go with them. When I walked out to see her, she was sitting upright on the stretcher, eyes half-closed from exhaustion. She looked smaller under the harsh lights, her wrists wrapped in gauze.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered.

She turned her head toward me, her voice hoarse. “Not your fault.”

But the look in her eyes said something different — that unspoken question of how I could have lived upstairs all those years, blind to what was happening below.

The ambulance doors shut, and for a moment I saw my reflection in the window beside her face: pale, hollow, unrecognizable.

When I turned back, Detective Hansen was waiting. “We’ll need you at the hospital too. The doctors will want to check you over, and we’ll take your clothes for evidence.”

“Evidence?”

She nodded toward my shirt, speckled with my father’s blood.

I hadn’t even noticed.

They drove me and Roger to the hospital in separate patrol cars. He met me in the ER waiting room, still pale but trying to act normal. “You okay?” he asked.

I almost laughed. “Define okay.”

He didn’t push. He just sat next to me in silence. The kind of silence that fills up a room when words can’t.

An hour later, Detective Hansen came back with updates. Sherry was stable but dehydrated and severely malnourished. The chain on her ankle had caused a deep infection. They were treating it, but she’d be admitted for at least a week.

I asked if I could see her, but Hansen said not tonight.

Then she told me they’d arrested my parents on charges of kidnapping, false imprisonment, and aggravated assault. They were being held without bail until the hearing.

I should’ve felt relief, but all I felt was empty.

At 3 a.m., a man in business-casual clothes appeared and introduced himself as Troy Hansen — the detective’s brother and a victim advocate for the county. He had this quiet steadiness about him, the kind of calm people borrow when their own world is collapsing.

He sat with me while I filled out paperwork I barely understood — witness statements, victim resource forms, safety plans.

When I finished signing the last one, I looked up and asked, “Where am I supposed to go?”

Troy hesitated. “Do you have anyone else? Friends, family?”

I thought of college classmates who didn’t really know me, of old friends who’d stopped calling years ago. I shook my head.

“Okay,” he said. “We’ll find you a place to stay tonight. Somewhere safe.”

He drove me across town to a crisis shelter, a converted brick building with bars on the windows and a lock buzzer at the door. The intake worker gave me a room with a single bed and a blanket that smelled faintly of detergent.

When Troy left, he handed me his card. “Call me if you need anything,” he said. “Anytime.”

After the door closed, I sat on the edge of the bed staring at the floor. The quiet was unbearable. Every time I closed my eyes, I saw Sherry’s face in that basement, pale and trembling, her eyes reflecting mine.

By sunrise, reporters had already found out. My phone buzzed nonstop with numbers I didn’t recognize. I turned it off and shoved it under the pillow.

A text from Troy came through later, somehow slipping past the silence mode: Don’t answer unknown calls. Reporters have your info. Only talk to me or Detective Hansen.

I typed back one word. Okay.

Then I lay back and stared at the ceiling until the pattern of the cracks started to look like chains.

The next morning started with a phone call from Detective Hansen.

My parents were being formally charged — kidnapping, false imprisonment, aggravated assault. It didn’t sound real, like hearing someone else’s nightmare read aloud.

By the time Troy picked me up, the hospital parking lot was already surrounded by cameras. News vans lined the street, reporters shouting questions at officers who ignored them. My parents’ house had become a headline before breakfast.

Inside, the air smelled like disinfectant and burnt coffee. Sherry was still in the trauma wing under police protection. They said she was stable, that the infection in her ankle was being treated, that she was strong. But the word “stable” sounded too thin for what she’d endured.

Troy led me down a corridor painted the color of old mint. “You don’t have to see her yet,” he said quietly. “You’ve both been through hell.”

“I need to,” I said.

The officer at her door nodded us in. Sherry sat up in bed, her wrists bandaged, hair braided loosely by a nurse. She looked cleaner, healthier, but her eyes still carried that haunted flicker.

When she saw me, she smiled — small and tired. “They told me you came with the cops,” she said.

I nodded. “I found the note.”

She looked away, staring at her hands. “I wrote a dozen of those, you know. Kept slipping them under the door whenever I thought someone was home. Guess you were the one who finally listened.”

My throat closed. “I should’ve listened years ago.”

She shook her head. “You couldn’t have known.” But her voice was flat, like she didn’t believe it either.

A nurse came in to change her IV. When she left, Sherry said quietly, “They were so careful, your parents. They kept music playing all the time — said the silence made them anxious. I didn’t even try to scream after a while. It never mattered.”

I wanted to apologize, to fix something, but the words jammed in my chest. All I could do was hold her hand.

Detective Hansen arrived later that afternoon. She briefed Sherry on what would happen next — forensic exams, evidence collection, interviews. Then she turned to me. “There’s going to be a bail hearing in two days,” she said. “Do you want to be there?”

“Yes,” I said, before she even finished.

“Then we’ll make arrangements.”

When I left the hospital, reporters had gathered at the entrance. Microphones thrust forward, flashes popping like gunfire. “Is it true you found the victim yourself?” one shouted. “Did you have any idea what your parents were doing?”

Troy pushed through them, his arm around me. “No comment,” he said. “Please respect her privacy.”

But they didn’t stop.

Back at the shelter, I shut myself in the room and scrolled through my phone despite every warning. The news sites had already plastered our family photo across the top of their pages: SUBURBAN COUPLE ARRESTED FOR HOLDING WOMAN CAPTIVE IN BASEMENT.

There I was, smiling between them. The daughter of monsters.

The article described the soundproof room, the chain, the tea laced with sedatives. It quoted a “source close to the investigation” saying the victim had been a friend of the family. I stopped reading after that.

Troy called that evening, checking in. “Don’t read the articles,” he said gently. “They’ll twist everything. Focus on staying safe and grounded.”

“I can’t stop thinking about what’s under that house,” I said.

He paused. “I know. But remember — it’s not your house anymore.”

The next day blurred together — interviews, statements, long silences in between. When I tried to sleep, I kept hearing the faint echo of chains dragging on concrete.

By the morning of the bail hearing, I hadn’t slept at all.

The courthouse was cold, the marble floors echoing with every footstep. Troy met me outside the courtroom with a coffee I didn’t drink. “You don’t have to go in,” he said again.

“I want to see them.”

Inside, my parents looked smaller somehow. The orange jumpsuits made them ordinary. Human. My mother’s hair was pulled back in a messy bun, her eyes red from crying. My father sat rigid beside her, hands cuffed, staring straight ahead.

The prosecutor — a woman named Selene Hansen, Detective Hansen’s sister — spoke first. She outlined the charges with crisp precision: kidnapping in the first degree, false imprisonment, aggravated assault, administration of sedatives without consent. Each word landed like a hammer.

She asked the judge to deny bail, arguing my parents were a danger to the community and a flight risk. She described the soundproofing, the restraints, the calculated planning.

Then their lawyer stood up — a man in an expensive suit with the kind of voice made for lies. He called it a “tragic misunderstanding,” said Sherry had come willingly and things “spiraled out of control.” He talked about my parents’ “longstanding contributions to the community,” their clean record, their family ties.

Family.

He meant me.

I wanted to scream.

The judge didn’t. He listened, flipping through papers, then announced bail: half a million dollars each, with ankle monitors, no contact with me or Sherry, and weekly check-ins.

I exhaled, relieved — until Troy leaned close and whispered, “They can afford that.”

Three hours later, they did.

When Troy told me they’d been released, my stomach turned. The walls of the shelter suddenly felt too thin, the windows too exposed. I imagined my parents walking free, driving home, planning.

That night, I dreamed of the basement again. Not Sherry this time — me, chained to the wall while my mother’s voice floated down the stairs, cheerful as ever. You brought this on yourself, honey.

I woke up shaking.

Troy texted an hour later: We’re adding extra security patrols near your shelter. You’re safe, I promise.

But I wasn’t sure I believed anyone anymore.

The weeks after the bail hearing blurred together.

Days passed in quiet routine — therapy sessions, police interviews, waiting for calls from Troy or Detective Hansen. But underneath everything hummed a low panic, like I was living inside the moment before an earthquake.

Then the evidence started coming in.

Detective Hansen called to tell me the lab had found sedatives in the tea tin from the basement, the same compound that matched Sherry’s bloodwork. There was DNA under her fingernails—my father’s. Her wounds lined up perfectly with the chain they pulled from the wall. Each new detail added weight to the truth I still couldn’t carry.

Selene Hansen, the prosecutor, asked to meet. Her office overlooked the courthouse, walls lined with case files that probably held a hundred other tragedies like mine. She was direct, efficient. She told me the prosecution’s case was airtight: forensic proof, receipts for the soundproofing materials, credit card charges dated months before Sherry disappeared.

Premeditation. That single word changed everything.

She explained that my testimony — finding Sherry, my parents’ reactions — was crucial to showing intent. “Are you willing to testify?” she asked.

The word yes sat heavy on my tongue. Saying it out loud meant reliving it in front of strangers. It meant describing the monsters who raised me while they sat ten feet away.

But I said it anyway. “Yes.”

Selene nodded. “Good. We’ll prepare you.”

The media didn’t stop. Reporters camped outside the shelter, snapping photos of every car that left. Headlines multiplied. “The Basement of Suburbia.” “The Perfect Family That Wasn’t.”

Every article felt like someone else writing my life, turning grief into spectacle.

Then one morning Troy called with news: the defense was negotiating a plea deal. My parents would admit guilt to every charge — kidnapping, false imprisonment, assault, drugging without consent — in exchange for a reduced sentence recommendation. Twenty-five to thirty years.

“Will they really say it?” I asked. “Out loud?”

“They have to,” Troy said. “It’s called allocution. They’ll have to describe what they did, detail by detail.”

The hearing was set for the following week.

I spent the days leading up to it writing my victim impact statement. Angela, my therapist, helped me find words that didn’t sound like screaming. She said, “It’s not about forgiveness; it’s about truth.”

I wrote about betrayal, about discovering the people who taught me right from wrong had no sense of either. I wrote about the guilt of missing the signs, the shame of sharing their blood. About hearing Sherry cry in her sleep in the hospital and realizing I’d been the one upstairs, safe, while she suffered below.

The morning of the hearing, I couldn’t eat. Could barely breathe.

The courtroom was full — reporters, neighbors, people who once waved at us from driveways. My parents sat at the defense table in orange jumpsuits. They looked old, shrunken.

The judge called the session to order. Selene summarized the plea: guilty on all counts. Then the judge turned to my parents and began the allocution.

He asked my father if he understood the charges.

“I do,” Dad said, voice flat.

“Describe what you did.”

Dad’s tone didn’t change. “We invited Sherry over under false pretenses. We drugged her. We kept her in a secured room in our basement. We restricted her movements. We harmed her.”

Hearing it like that — stripped of emotion — made it worse. Like torture could be recited from a manual.

Mom cried through her turn. “We thought we were helping her,” she sobbed. “We didn’t mean—”

The judge cut her off. “You planned it. Say it.”

Her voice cracked. “We planned it.”

The courtroom stayed silent except for the scratching of the stenographer’s keys.

When they were done, Selene called Sherry to the stand. She walked slowly, her scars visible under the cuff of her sleeve, and read from a folded piece of paper. Her voice trembled, but her words were knives. She described three years of darkness, the fear, the pain, the hunger, the smell of bleach and metal. She said she still woke up hearing my mother humming through the floorboards.

Then she said, “You didn’t break me. You caged me, but you didn’t win.”

When she stepped down, the judge asked if there were any other statements. I stood up.

My paper shook in my hands, but my voice didn’t.

“I grew up believing my parents were good people,” I said. “They taught me that home was safety, that love was protection. Now I know home can be a prison, and love can be a lie. They didn’t just destroy Sherry’s life — they destroyed mine too, because I have to live knowing I didn’t see it. But we’re still here. We survived them.”

When I finished, the judge nodded slowly, like he felt the weight of the words. Then he sentenced them: twenty-eight years each.

No one spoke after the gavel fell. The bailiffs led my parents away in handcuffs. Mom turned once, her eyes red, but I didn’t look back.

Outside, the air was warm, the sunlight too bright. Sherry stood beside me, her hair tied back, her hands still bandaged. We didn’t say anything. We just stood there, breathing in air that finally felt clean.

“This isn’t the end,” she said quietly.

“I know,” I told her. “It’s just the part where we start living again.”

News

I won $333 million in the lottery. After years of being treated like a burden, i tested my family called saying i needed money for meds. My son just blocked me. My daughter just said figure it out, not sick. But my 20-year-old sick son drove 400 miles with his last $500

I won $333 million in the lottery. After years of being treated like a burden, I tested my family by…

When I Learned My Parents Gave The Family Business To My Sister, I Stopped Working 80-Hour Weeks For

When I learned my parents gave the family business to my sister, I stopped working 80our weeks for free. Dad…

I bought a mansion in secret. Then one afternoon, I caught my daughter-in-law giving her family a grand tour. “The master suite is mine,” she declared proudly. “And my mom can take the room next door.” I stood in silence, hidden in the hallway, listening to every word. I waited until they finally left. Then I changed every single lock, one by one. And I installed security cameras. What those cameras captured later… left me speechless.

“I waited for them to leave, changed every lock, and installed security cameras. If you’re watching this, subscribe and let…

HOA Karen Tripped My Pregnant Cousin on the Sidewalk — 10 Minutes Later, SEALs Surrounded Her

Can you believe it? This woman just intentionally tripped a five-month pregnant woman on a public sidewalk and actually smiled…

My Parents Gave My Room To My Brother Because He Needed More Space. They Laughed, Expecting Me To Sleep On The Floor. But I Said I Would Be Moving Into The New House I Just Bought And They Went Silent…

Part 1 — The Dinner I should have known something was off the second I heard my mother’s voice on…

At My Daughter’s Birthday Party, My Mom Tried To Take Her College Fund To “Help” My Sister Pay Her Debts. So I Announced I Had Closed The Account Last Month, And Her Reaction Ended Everything…

I grew up believing that money was love. My mother, Patricia, taught me that without ever saying it outright.Every allowance…

End of content

No more pages to load