The Impossible Dawn – June 6, 1944

For Oberleutnant Klaus Richter of the 352nd Artillery Regiment, dawn on the Normandy coast began like countless others—gray, damp, and silent. A fine mist rolled off the Channel and clung to the dunes, muffling every sound but the faint hiss of the wind through barbed wire.

It was just after five a.m. Another watch. Another morning of waiting for an invasion that might never come.

He lifted his Zeiss binoculars toward the horizon. The first weak light of day was rising, and the line where sea met sky began to thicken. At first he thought it was fog. Then his heart stopped.

The line grew darker, sharper. It multiplied. It was not a weather front. It was ships—hundreds of them—emerging from the mist. A city of steel moving steadily toward France.

Before the world knew the names Omaha or Utah, Richter understood what he was seeing:

the Reich was about to drown.

Fortress Europe, 1944

To understand his shock, you have to remember what the German soldier was told to believe.

From Norway’s cliffs to Spain’s border, the Reich had built the Atlantic Wall—a concrete chain bristling with guns and mines. Propaganda called it impenetrable. Berlin swore it could stop anything.

Richter knew better. At 32, a veteran of the Eastern Front, he had long since learned the distance between propaganda and reality. His battery sat in reinforced casemates a few miles inland from beaches code-named by the enemy as Omaha. The men were diligent but weary—veterans mixed with boys and old reservists. They drilled, cleaned the guns, and watched the gray horizon. Everyone spoke of Der Tag X—the day of days—but few believed it would find them.

The German Miscalculation

German intelligence was convinced the Allies would land at Pas-de-Calais, the narrowest point of the Channel. The 15th Army, Germany’s strongest, waited there. Normandy was dismissed as a sideshow.

The error was deliberate—Operation Fortitude, the Allied deception that fed false radio traffic and dummy armies to German spies. It worked. By June 1944 the defenders of Normandy were exposed and under-manned.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, responsible for strengthening the coast, understood the real danger. “If we do not stop them on the beaches,” he warned, “we lose the war.” He demanded millions of mines, thousands of obstacles—the men jokingly called them Rommel’s asparagus. But the system above him refused to listen. And when storms swept the Channel on June 5, the meteorologists assured everyone an invasion was impossible. Even Rommel left for Germany to attend his wife’s birthday.

So as Richter stood watch in the pale half-light of June 6, the mood was routine. The storm had passed. The sea was rough but empty—until it wasn’t.

The Sea Turns to Steel

A flicker. Then hundreds.

Through his binoculars Richter watched the horizon dissolve into shapes—warships, transports, landing craft by the thousand. The entire Channel was alive with movement.

He tried to count, failed, tried again. Battleships loomed like black cliffs; destroyers darted around them like wolves. Between them swarmed a carpet of landing craft so dense they seemed to erase the water itself.

Later historians would tally nearly 7,000 vessels from eight nations, the largest armada in human history. To Richter it was not a statistic. It was the horizon itself made solid—proof that Germany’s wall of concrete faced a bridge of iron.

He seized the field telephone.

“Observation Post Four. I have visual contact—ships. Thousands.”

The voice on the other end yawned. A few ships, perhaps a raid. Stand by.

“Not a raid,” Richter shouted. “It’s the invasion! For God’s sake, look at the sea!”

Static. Disbelief. Higher command could not grasp what he described. Their maps, their forecasts, their certainty—none of it had room for what was happening before his eyes.

So Richter acted on his own.

First Fire

He ordered his men to action. Shells clanked up from the magazines; rangefinders called out impossible numbers. At 5:58 a.m. his guns roared for the first time in months. The concussion shook the bunker; tracer shells streaked across the water.

He watched one salvo walk its way into the fleet—and then a burst of flame.

An American destroyer—the USS Cory—erupted in smoke. Whether from shell or mine, he never knew, but his men cheered. For a heartbeat it felt like victory.

Then the feeling died.

The fleet did not scatter. The hole closed instantly, the formation unbroken. Ship after ship steamed forward, endless, unstoppable. Richter realized he was trying to drain the ocean with a bucket.

The Allied Reply

A distant rumble rolled across the water. He looked up to see flashes—dozens—blossoming along the horizon. Seconds later the world dissolved in thunder. The earth convulsed; fountains of dirt and smoke exploded around the battery. The Atlantic Wall was being torn apart stone by stone.

Where were the panzers? The Luftwaffe?

Richter looked skyward and saw only enemy planes—waves of fighters, bombers, transports. The air belonged entirely to the Allies.

The nearest tank division, the 21st Panzer, sat paralyzed awaiting orders from Berlin. When it finally moved, Allied aircraft ripped it to pieces.

Watching his own guns fire into the storm of steel, Richter understood: this was not a battle.

It was an erasure.

The Industrial War

Through the smoke, his mind’s eye saw not ships but factories—the assembly lines of Detroit and Buffalo, the steel mills of Pittsburgh, the shipyards of Boston. Each salvo that pounded the coast was the echo of a thousand machines turning somewhere far from Europe.

For every Tiger tank Germany built, America rolled out twenty Shermans.

In 1944 the United States produced 29,000 tanks; Germany, barely 2,000 a month.

The Allies flew 14,000 sorties on D-Day; the Luftwaffe managed 300.

It wasn’t courage that failed the Reich—it was arithmetic.

Richter felt an almost spiritual despair. His men were brave, skilled, doomed. They were craftsmen fighting a machine. A sword against a steam hammer. The outcome had been decided before the first shot.

Omaha Beach

At 6:30 a.m. the landing craft dropped their ramps. Through his periscope Richter saw dark figures splash into the surf—American infantry wading straight into machine-gun fire. The sea turned red. For a moment the defense held. The 352nd Division exacted a terrible price.

Then the destroyers closed in—within a thousand yards of shore—firing point-blank into the bunkers. Sand spouted skyward; concrete shattered. Behind them came strange amphibious vehicles, tanks with flails, trucks driving out of the waves—Hobart’s Funnies, inventions built for this very beach.

The Germans had nothing like them.

By midday, strongpoints were collapsing one by one under the combined weight of naval guns, tanks, and bombs. Richter’s own battery took direct hits; communications died. When he looked up, the sky was filled with Allied aircraft, the sea with the next wave of landing craft. It was endless—a conveyor belt of men and steel.

The beach was lost; the war, in truth, already decided.

Aftermath

The fight for Normandy would grind on for two more months, but its outcome was sealed that morning. Every German tank destroyed was irreplaceable; every Allied tank lost was replaced by three more. The mathematics of industry had taken command of strategy.

For Oberleutnant Klaus Richter, and for thousands like him, the rest of the war was an epilogue—duty without hope. They fought because that was all that remained to them.

And when we picture the fall of the Third Reich, we often imagine the ruins of Berlin in 1945.

But for the men on the Atlantic Wall, the end came here—in one blinding dawn over the Channel, when the mist lifted to reveal a horizon made of steel.

It was the morning they saw that the modern world had arrived—and that nothing, not courage, not faith, not ideology, could stop it.

The Impossible Dawn – Part 2: The Longest Day

The morning that had begun with disbelief turned before noon into a nightmare of precision.

Inside his shattered observation bunker, Oberleutnant Klaus Richter could no longer hear individual sounds—just one continuous roar: naval shells, aircraft diving, the hammering of his own surviving guns. The Atlantic Wall was supposed to roar back. Instead it groaned, cracked, and slid toward oblivion.

Outside, men moved like ghosts through powder-gray smoke. Orders were shouted but lost in the wind. Telephones were dead. The field radio was nothing but static. From time to time, Richter would crawl to the narrow observation slit, wipe the dust from the lenses of his binoculars, and look out on the end of an era.

A Shoreline of Fire

Where sand had met surf hours before, there was now only churned mud and wreckage. Landing craft burned; tanks struggled through water turned to sludge; bodies rolled with the tide. Yet still they came. The sea itself seemed to deliver men to the continent without pause.

Behind them, warships pounded the hills with perfect, mechanical rhythm. Every explosion shook Richter’s lungs. He caught flashes of the battleships’ broadsides, slow arcs of red fire crossing the sky. It was methodical, impersonal—a factory at work.

“Keep firing,” he said hoarsely. His crew obeyed, dragging shells through the smoke, feeding the breeches like coal stokers on a doomed ship. When one gun jammed, they fought to free it until another shell hit the emplacement and ended the argument forever.

At 0930 a runner from a nearby company stumbled in, covered with blood that wasn’t his own. “They’re through at Vierville,” he gasped. “The Yanks have armor ashore.”

Collapse

By late morning, the precision of the Allied bombardment was terrifying. Planes shrieked in endless circles overhead; parachutes drifted far inland, ghostly white against the green fields. German positions that had been plotted for years were disappearing one by one. The 352nd Division was being erased from the map.

Richter crawled to the field telephone again, though he knew the line was dead. Habit demanded the gesture. He repeated a useless report into the void:

“Enemy strength overwhelming. Situation untenable.”

Static answered.

He glanced toward his remaining crew—boys, mostly, faces gray with soot. “Fall back to the secondary line,” he ordered, though there was no secondary line anymore. He waited for one last salvo, then shouted, “Raus!” and they slipped from the bunker into the churned earth.

Retreat Through the Smoke

They moved in short bursts, crouching among craters, the air thick with cordite. Behind them the sea sounded like a storm breaking against metal cliffs. Allied shells fell farther inland now, searching for batteries like his. The world shrank to the space between impacts.

At the crest of a hill he turned once more toward the coast. From here he could see the pattern entire: ships stacked in orderly lanes, the thin black thread of beaches crawling with movement. It looked less like a battlefield than an assembly line that stretched to the horizon.

For the first time since Russia, Klaus Richter felt fear without anger. There was no enemy to hate—only an equation that had already been solved.

The Industrial Truth

He understood now that this war had been decided in factories, not fortresses.

He thought of Detroit, of Pittsburgh, of the endless trains rolling out of the American heartland. For every cannon he lost, they forged a hundred. For every plane they lost, they built forty more. Germany’s genius for engineering had built marvels, but too few of them, too late.

In his mind, ideology melted into arithmetic:

one Reich versus an economy that spanned half the planet.

He whispered to no one, “Wir sind fertig.”

We are finished.

The Afternoon Turns to Ash

By midday the sun had burned the mist away, revealing a coastline that no longer belonged to Germany. Allied engineers were already erecting signal masts and bulldozing exits off the beach. Trucks rolled ashore on steel mats, carrying ammunition, food, gasoline. The invasion wasn’t a single blow; it was a conveyor belt of power.

Richter reached a farm road where scattered survivors of the 352nd were regrouping. The men’s eyes were hollow. They carried rifles without bolts, machine-gun barrels too hot to touch. Someone muttered about counterattack orders coming from corps headquarters, but no one believed it. Every officer who still had a map knew the line was gone.

He sat on a broken wall and lit a cigarette. The smoke tasted of salt and gunpowder. In the distance, the thunder rolled on, steady, tireless. It would roll for months.

Epilogue of the First Day

That night, as darkness returned to the shattered coast, the Allies were still landing troops—over 156 000 men on the first day alone. Germany’s western wall had cracked open, and through the gap poured the future.

Richter survived the day. He would spend the following weeks retreating through hedgerows, through villages reduced to rubble, through the slow realization that the war was no longer a contest of courage but of capacity.

Years later, when he spoke of that morning, he never mentioned fear or heroism.

He spoke of the sound—the steady hum of engines beyond counting—and of the moment when the sea itself seemed to rise against him.

It was, he said, the hour Germany learned that the modern world could not be stopped by concrete, or courage, or prayer.

It was the impossible dawn—the morning the Reich met the age of machines.

The Impossible Dawn – Part 3: The Fall of the Wall

The Night After D-Day

By the evening of June 6 th, the world that Klaus Richter had known no longer existed.

Behind him, his battery was a smoking cavity. The concrete roof that had promised safety had caved in on the last gun crew. Ahead, the black outline of the coast glowed red and orange—fires from ruptured fuel drums, shattered trucks, and burning villages.

He and a handful of survivors moved inland under a moon veiled by smoke. The sounds of war no longer came in volleys but as a constant mechanical heartbeat. The Allies had landed their rhythm, and it would not stop again until Germany itself stopped breathing.

They marched through the hedgerows, past cattle carcasses and the twisted bodies of their own comrades, each step sinking into soil soaked with seawater and blood. The men said little. There were no officers left to shout at them and no orders that made sense anymore.

The Collapse of Command

At a crossroads outside Colleville, they met a column of retreating infantry—young, exhausted, still carrying heavy machine-gun tripods they would never set up again. Every rumor that passed among them told the same story: no fuel, no air cover, no reinforcements. Headquarters had lost contact with almost every coastal unit.

One radio operator insisted that Hitler himself had refused to release the Panzer reserves until midday, convinced that Normandy was only a diversion. By the time the tanks began to move, Allied aircraft had turned the roads into rivers of fire.

To the men trudging through the dark, it was not strategy anymore; it was punishment from the heavens.

The Daylight Offensive

At dawn on June 7 th, the thunder began again. Allied artillery had come ashore, their shells answering the battleships’ guns from the landward side. Richter crouched in a ditch and watched American paratroopers fan out across the fields. They moved with quiet, terrifying efficiency—no bluster, no hesitation, just the momentum of inevitability.

He tried to imagine stopping them with the fragments of his regiment. The idea was absurd. They had two working field guns, a single truck half-filled with diesel, and no contact with corps headquarters.

By afternoon, they were simply trying to survive long enough to retreat toward St. Lô.

The War of Machines

Richter’s old faith in tactical brilliance, in the clever ambush or perfectly calculated artillery pattern, evaporated with each column of Sherman tanks that rolled past the horizon. The American advance wasn’t brilliant; it was industrial. It looked the way an assembly line might look if it could march—constant, repetitive, efficient.

He realized that even if the Germans destroyed one column, another would replace it within hours. Each tank, each truck, each rifleman was a moving part in something far larger than any single battle. The Allies fought like a machine that repaired itself as it went.

His own army fought like a craftsman’s shop—meticulous, courageous, doomed.

The Sky That Never Slept

By June 8 th, the sky itself had changed allegiance. Bombers moved above the clouds in organized layers, their contrails sketching white grids against the blue. Every time the Germans tried to move by day, the grids descended in fire. Even at night, tracer lines arced across the dark like fiery stitches sewing the continent shut.

Richter’s men began moving only at dawn and dusk, hiding under trees during the day, their trucks covered with branches. The effort felt theatrical—camouflage against omniscience. They whispered that God had chosen a side, and He was flying a star-spangled roundel on His wings.

Letters Never Sent

In a barn they commandeered for shelter, Richter found an old field desk and sat down to write a report that would never reach its destination. The paper trembled under his pencil:

To Regimental Command—Battery Four no longer operational. Casualties severe. Enemy strength overwhelming. Recommend immediate withdrawal to new defensive line east of Bayeux.

He paused, then added a single line beneath it:

The wall has fallen.

He folded the sheet, not knowing why—habit, perhaps—and slid it into his pocket.

The Realization

That evening, sitting against a stone wall while distant artillery flashed against the clouds, Klaus Richter finally understood what had happened on June 6 th.

It wasn’t merely that an army had landed; it was that an era had ended.

The Germany that had marched across Europe believing in willpower and genius had collided with a civilization that fought by multiplication. He thought of the Allied soldiers now bivouacked on the beaches, eating canned meat, listening to portable radios, laughing. They had come from a world of factories, railroads, and steel mills that could replace anything they lost. And that world had decided to bury his.

Beyond Normandy

By mid-July, what remained of the 352 nd Division was folded into another corps and pushed back toward Caen. The Americans had turned the beaches into ports, unloading locomotives and entire fuel pipelines. Every road became a conveyor belt of trucks. The once-proud Atlantic Wall was being scavenged for material to build new Allied fortifications.

When Caen finally fell, Richter and the survivors were captured in the hedgerows south of the city. The young sergeant who searched him found the folded note in his tunic and looked at it for a long time before tucking it back.

“You were right,” the sergeant said quietly in English. “The wall’s gone.”

Richter nodded. There was nothing else to say.

Epilogue

Years later, when historians argued about strategy—about the weather forecasts, Rommel’s absence, or the timing of the Panzer counterattack—none of them quite captured what Richter had seen that morning.

He remembered the sound before dawn, the low hum spreading across the water, a sound so deep it seemed to vibrate inside his bones. It was the sound of an age beginning.

For the men in the bunkers, the war ended the moment the horizon turned to steel. The rest was only the long echo of that impossible dawn.

The Impossible Dawn – Part 4: The Machinery of Fate

The Long Retreat

By July 1944, the front in Normandy had dissolved into a maze of rubble, smoke, and endless dust.

For Oberleutnant Klaus Richter, the weeks after D-Day were not a battle—they were erosion.

Each morning he woke farther from the sea, farther from the line he had sworn to hold. Every town name they passed—Trévières, Saint-Lô, Périers—was just another scar on the map.

The army still issued orders, but the orders no longer described the world they lived in. They spoke of “reorganizing sectors,” of “counterattack possibilities.” Richter knew they meant only one thing: keep moving east until you can’t.

The men who followed him were ghosts of the regiment he had commanded. Boys who had never fired their rifles in training were now veterans because they were still alive. They carried what food they could find, scavenged from abandoned supply dumps or empty French barns. Sometimes French farmers left bread by the road; sometimes they spat at the Germans as they passed. Richter no longer blamed them. If he had been French, he would have done the same.

The Collapse of the Luftwaffe

Above them, the sky never rested. Allied planes flew in sheets—silver by day, black silhouettes by night.

The Luftwaffe, once the pride of Europe, was almost gone. The few German fighters that appeared were hunted instantly, swarmed out of the air. Richter watched one dogfight from a hedgerow: a Messerschmitt twisting in desperate loops while three Thunderbolts took turns firing until the German pilot’s wings folded. The wreckage burned for hours.

He remembered how in 1939 the soldiers had marched beneath those same aircraft, cheering, certain they were invincible. Now he wondered if every empire sounded like that in its first spring—confident, unstoppable, blind.

St. Lô: The City of Rubble

When the division regrouped near St. Lô, there was little left to command. The city had been bombed so often that the roads were clogged with broken stones instead of vehicles. Refugees shuffled through the ruins carrying bundles and white flags. The smell of death had settled into everything—earth, cloth, skin.

On July 18 th, Allied bombers flattened what remained. Richter’s company spent two days digging themselves out. He emerged into sunlight so thick with dust it looked like dusk. Around him, men wandered dazed between shattered buildings. Someone joked weakly that the Americans were trying to bury them alive. No one laughed.

That night he wrote in his notebook:

The air is louder than God. We fight the sky itself.

The Breakout

By August, the Allies had broken through at Avranches. Tanks poured south like floodwater. The German front folded in half. Orders came to pull back toward Argentan, to hold an imaginary line that existed only on maps. Units moved without coordination; trucks collided at crossroads; ammunition wagons were abandoned for lack of fuel.

Richter’s battery—down to one field gun—fired its last shells at the advancing Americans and then spiked the weapon. He told his men to take only what they could carry. They walked east again, chased by thunder.

When Allied planes attacked, they scattered into ditches. One afternoon, Richter watched as a young corporal froze instead of diving for cover. The bombs missed them, but the blast flung the boy head-first into a stone wall. He died without a mark on him. Richter covered the body with a rain cape. The next morning he couldn’t remember the boy’s name.

The Falaise Pocket

In mid-August, the retreat turned into a trap. Allied forces closed in from north and south, sealing the Falaise Pocket. The roads out were jammed with columns of trucks, tanks, horses, and thousands of soldiers trying to escape before the ring closed. The air stank of oil and corpses.

Richter’s group joined the night exodus along a narrow lane lined with burning vehicles. Artillery shells fell like rain. At one point a bomb struck a fuel truck ahead of them, engulfing the road in flame. The men dropped their packs and ran through the smoke. Behind them, the entire column exploded in a roar that drowned out their screams.

By dawn the gap at Chambois was closing. Allied tanks had reached both sides. Richter and a few others crawled through the fields, sliding over dead horses and shattered wagons. When they finally reached open ground, they collapsed among a crowd of surrendering soldiers. British troops herded them together, rifles ready but eyes weary.

It was over.

Captivity

The prisoners were marched west—back toward the beaches that had destroyed them. For days they trudged through the wreckage of Normandy. The countryside that had once been orchards and farms was now a landscape of twisted metal. They passed endless rows of Sherman tanks, each marked with chalk kill-tallies, each proof of an industry that never slept.

At an improvised camp near Isigny, the Americans fed them canned rations and kept them behind barbed wire. For the first time in months, Richter felt something like safety. The guards were polite but distant. When one of them offered him a cigarette, he realized with shame that he had forgotten the English word for “thank you.”

The Weight of Numbers

In captivity, rumors replaced news. Some said Paris had fallen; others claimed the Russians were at Warsaw. None of it mattered. The men could feel the truth in the ground itself. The trains heading east no longer carried soldiers—only refugees and coffins.

An American intelligence officer asked Richter about German artillery tactics. He answered honestly, though it felt meaningless. What could tactics matter against arithmetic? For every cannon Germany built, the Allies built ten; for every factory Germany lost, they captured two more. He said as much. The officer only nodded, as if he had already known.

The Realization

Weeks later, Richter was transferred to a larger camp in England. From there he could see the Channel glittering in the distance, the same water he had stared across on June 6 th. At night he could hear ships moving—convoys heading east now, toward a continent being freed.

Sometimes he thought about the note still folded in his tunic pocket, the one the American sergeant had returned to him: The wall has fallen.

He considered throwing it away but never did. It was a reminder that he had witnessed the exact moment history had changed direction.

When he closed his eyes, he still saw that first line on the horizon, the impossible city of steel sliding out of the mist. He knew now that nothing he or anyone else had done afterward had truly mattered. The war had been decided in that instant—when the tide brought not just an army, but the weight of an entire modern world.

Epilogue

In the years after the war, Klaus Richter never returned to the army. He worked quietly as an engineer, rebuilding bridges instead of destroying them. Sometimes, when people asked where he had been during the war, he would answer only, “On the morning the world arrived.”

Because that was what it had felt like on the Normandy coast—

the moment the twentieth century itself came ashore,

and the age of fortresses, flags, and faith gave way to the age of machines.

The Impossible Dawn – Part 5: The Aftermath of the Machines

The Camp

Winter came early that year in England. In the prisoner compound near Suffolk, where Oberleutnant Klaus Richter and thousands of captured soldiers now lived, frost rimmed the barbed wire before dawn. The Americans had organized everything with the same efficiency that had crushed the Atlantic Wall: clean barracks, latrines, roll call at exact times. To men who had survived chaos, it felt almost merciful.

Richter spent his mornings repairing generators for the camp. The Americans quickly learned he was an engineer and trusted him with tools. At first he worked in silence, afraid of saying anything that would sound like politics, but the guards treated him with weary professionalism. Once, a sergeant asked him what he thought about D-Day. Richter’s answer came out before he could stop it.

“It wasn’t a battle,” he said quietly. “It was the future arriving.”

The sergeant stared at him, then nodded. “Guess that’s one way to see it.”

Letters Home

Mail came irregularly. In December, Richter received his first letter from his sister in Hamburg. The city, she wrote, had been flattened in the July bombings. Their parents’ house was gone; the factory where his father once worked had been turned into a heap of twisted girders. “Everything is ashes,” she wrote. “But at least the fire has stopped.”

He folded the paper carefully and kept it in his pocket beside the note he had written on June 7: The wall has fallen. The two scraps of paper seemed to belong to the same sentence.

When censorship loosened in 1945, he began writing back. His letters contained no ideology, no excuses—just the slow understanding that the war had been a machine eating itself. “We believed we were men of destiny,” he wrote, “but we were parts in an engine that no one could shut off.”

The News from the East

In the spring, rumors filtered through the camp that Berlin had fallen and Hitler was dead. At first, no one reacted. They had all rehearsed that moment too many times in their minds. When official confirmation came, a few men cheered, a few wept, but most simply sat staring at the ground. For Richter, it was anticlimax. The true end had happened a year earlier, when the mist had lifted off the Channel.

One evening an American officer gathered the prisoners in the mess hall and read aloud the full surrender declaration. The officer’s voice was flat, almost gentle. When he finished, there was a long silence. Then someone in the back whispered, “So it’s really over.”

Richter thought, No. It ended when we met the age of steel.

Repatriation

By late 1946, the camp began to empty. The younger men went home first; engineers and officers were kept longer for questioning. When Richter finally crossed the Rhine again, he found Germany unrecognizable. Cities looked like the photos of moonscapes in pre-war science magazines—craters, skeletons of buildings, streets leading to nothing. He traveled to Hamburg, found his sister in a temporary housing block, and took a job with the British reconstruction office repairing bridges. Steel again—but this time as salvation, not conquest.

At night he sometimes walked to the river and watched barges move under the new floodlights. The sound of diesel engines echoing through the fog reminded him of that other morning two years earlier. It no longer frightened him. The noise meant commerce, rebuilding, life.

The Age That Followed

In 1948 he was hired by a civilian firm contracted to rebuild sections of the Autobahn. The work was steady, the pay modest, the silence inside him finally bearable. Allied trucks rumbled along the repaired stretches carrying machinery and food instead of soldiers. Germany was learning to survive by joining the very system that had defeated it—the industrial rhythm of the modern world.

Sometimes, when foreign engineers visited, they asked polite questions about his wartime experience. He always answered the same way:

“I saw the wall fall. I saw what happens when belief meets production.”

They would smile uncertainly, not sure if it was philosophy or confession.

Memory

By the time the 1950s arrived, Klaus Richter lived quietly with his wife and son outside Hanover. He rarely spoke of the war except to warn his students at the technical school where he later taught: Never mistake ideology for engineering. To him, the moral lesson and the mechanical one were the same. You could not build a future on myths, only on materials.

Each June he rose early on the sixth, made coffee, and stepped into the yard. When dawn lightened the sky, he could almost hear the low hum of engines across the years. He would stand for a long time, remembering that thin gray line on the horizon and the day when the sea became steel.

Then he would whisper a simple truth that his son, overhearing once, never forgot:

“That morning, the world grew too large for war.”

And with that, he would turn back inside, leaving the impossible dawn where it belonged—in memory, at the edge of the sea.

The Impossible Dawn – Part 6: The Last Horizon

The Years of Rebuilding

By the 1960s, the new Germany was almost unrecognizable to the men who had fought for the old one.

Cities that had once been rubble now glittered with neon. Factories hummed again—not for conquest but for commerce. Children grew up without ration cards, and the smell of diesel in the air meant prosperity, not war.

Klaus Richter, now in his fifties, wore a suit instead of a uniform. He managed an engineering department that designed industrial cranes—machines that could lift hundreds of tons of steel into the sky. Sometimes, while supervising tests at the harbor, he would pause as the cranes’ engines roared and the cables groaned under strain. The sound carried him backward—to June 6, 1944, to the hum of the invasion fleet.

But where once that sound had meant destruction, now it meant construction. The same forces that had crushed him—industry, logistics, machinery—were rebuilding his country. It was an irony he carried like a medal no one else could see.

The Unspoken Past

Germany rarely talked about the war then. People were too busy living. Richter noticed it everywhere—in newspapers, in classrooms, in dinner conversations that stopped at certain words.

The silence was polite, almost hygienic. But underneath it lay something unresolved.

He sometimes lectured at the university in Hamburg on engineering ethics. Once, after a seminar, a student asked timidly,

“Herr Richter, were you in the war?”

He looked at the young man’s earnest face and saw curiosity, not accusation. “Yes,” he said simply.

“On which front?”

“The one that ended first,” he replied. The student frowned, not understanding, and Richter let it go. He had no desire to explain that his “front” had collapsed not from defeat but from realization.

That was what most people never grasped about Normandy—it wasn’t only a military disaster; it was an existential one. It proved that belief and courage, stripped of resources and reason, were just noise before the machine.

Return to Normandy

In 1969, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of D-Day, a veterans’ organization invited Richter to return to France. He almost declined. But curiosity, or maybe unfinished penance, brought him back.

The ferry crossing from Portsmouth was calm. The same waters that had once heaved with seven thousand ships now carried tourist liners and fishing trawlers. When the French coast appeared through the mist, Richter felt the old chill rise in his chest. For a moment it was June 6 again—the horizon a gray bruise against the sky.

He rented a car and drove the narrow coastal road toward Omaha Beach. The modern highway signs pointed the way with cheerful precision: Musée du Débarquement, Parking Gratuit. Where gun casemates once stood, there were cafés and souvenir stalls. The sand was golden, the sea calm, children building castles from it. He stood there a long time, the wind in his coat, watching the tide erase footprints.

In the small military cemetery above the cliffs, the rows of crosses stretched in perfect geometry. He counted neither names nor nations; they all looked the same from this distance. He left a single flower—not on any grave in particular, but at the center of them all.

The Meeting

As he was leaving, an elderly American in a gray raincoat approached him. They nodded to each other in the awkward fraternity of survivors.

“You were here?” the American asked, his accent heavy with years.

“Yes,” Richter said. “On the other side.”

The man studied him for a moment, then offered his hand. “Hell of a day,” he said quietly.

Richter shook his hand. “Hell made men,” he answered. “Machines ended them.”

They stood in silence for a while, two soldiers from opposite horizons, watching the surf. Then the American smiled faintly. “Guess we finally built something worth keeping, huh?”

Richter followed his gaze to the memorial, gleaming in the sunlight. “Yes,” he said. “We built memory.”

Understanding

That evening, he sat at a seaside café overlooking the Channel. The water was silver under the setting sun. He thought of his son back in Hanover, an engineer like him, building bridges for the new Europe. The old man smiled, realizing that in some strange way, the invasion he had once tried to stop had made this peace possible.

He took out his wallet and unfolded the same note he had written twenty-five years before. The paper was brittle now, the ink fading:

The wall has fallen.

He laid it on the table, pressed flat under his coffee cup, and looked out to sea. The tide was rising again, slow and relentless, washing away every trace of the bunkers and scars he remembered. He thought of his comrades, of the countless faces lost to the churn of history, and whispered:

“It was never our world to keep. We were only the first to see it coming.”

The End of the Story

Klaus Richter died in 1974, quietly, at home in his sleep. His wife found the note in his desk drawer, folded beside a small photograph of Omaha Beach taken on that last trip. She kept both in a frame, unaware that the words captured an entire century.

In the decades that followed, the world continued to turn faster—computers, satellites, new wars fought by machines he could scarcely have imagined. But every generation that crossed the Channel to stand on that shore, every student who learned about the battle, was living proof of what he had realized that first impossible dawn:

That no fortress, no ideology, and no empire can withstand the full momentum of human progress once it begins to move.

And so the story ends where it began—on a gray morning, with the sea rising toward the cliffs and a single man standing at the edge of history, watching the horizon change color.

News

💔 “LOVE YOU. ALMOST DONE.” — HIS LAST TEXT ARRIVED AT 14:57. SHE NEVER SAW HIM AGAIN. 🕯️🔥 Firefighter Ho Wai-ho had just one shift left before meeting his fiancée to try on wedding rings. By sunset, he was gone — found face-down in the ashes of Wang Fuk Court, still gripping the hose. The city is mourning, the headlines are raw, but it’s one photo — and one unfinished promise — that has broken Hong Kong’s heart. What was supposed to be a normal shift turned into a hero’s last stand. And somewhere, a woman in a dress she may never wear is still whispering the question no one can answer. 👇

Before the flames, there was a promise. And when the smoke cleared, only silence remained. In the worst fire Hong…

💔 “YOU WANT TO CLEAN UP AMERICA? START WITH YOUR SOUL.” — KAROLINE LEAVITT JUST GOT A LETTER THAT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO IGNORE 😢🔥 Karoline Leavitt has been silent for weeks. But today, her cousin’s sister — Graziela Dos Santos Rodrigues — broke that silence wide open with a public letter that’s already shaking political feeds. In it, she names names. She calls out power. And she asks one devastating question: how can Karoline preach about “protecting families” while her own blood sits in an ICE cage, and an 11-year-old boy cries himself to sleep waiting for his mother? This isn’t just a plea — it’s an indictment. And once you read the final paragraph, you won’t forget it. 👇

It began as a letter — handwritten, emotional, personal. Within hours, it became a political firestorm. When Graziela Dos Santos…

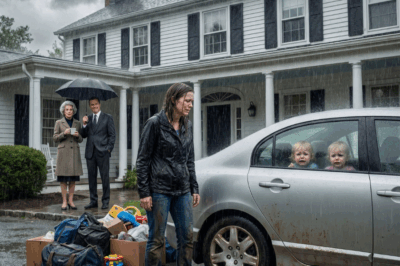

Unaware of Her 200million Inheritance, Her in laws threw her and her twins out after husband died…

It was raining so hard the sky looked like it had cracked open, and I swear the sound of water…

“I only ordered for family,” my mother-in-law smiled when my aunt asked why I got no steak or dessert.…

I only ordered for family, my mother-in-law smiled when my aunt asked why I got no steak or dessert. Am…

He missed his flight to help an elderly veteran — then the terminal was cleared without explanation

Don’t worry, sir, I’ll stay with you until someone comes. The young man said it calmly, helping the elderly veteran…

When I collapsed at work, the doctors called my parents. They never came. Instead, my sister tagged me in a photo…

When I collapsed at work, the doctors called my parents. They never came. Instead, my sister tagged me in a…

End of content

No more pages to load