Part One: Maple Avenue in Autumn

Columbus in October looked like a postcard someone forgot to mail. Maple Avenue wore its trees like feathered boas—reds and russets, shocks of gold—and the breeze had learned the trick of touching faces without stealing any warmth. Michelle Roberts stood at the kitchen window of the little house she and her husband had spent five years making into a home and cradled a mug in both hands. The coffee had cooled, but it gave her something to hold—heat you could count on, unlike the rest of life with its mysteries and uncooperative timelines.

Her studio—really a corner she’d annexed with painter’s tape and stubbornness—perched just off the kitchen. The desk bore a neat scatter of Pantone swatches and test prints, a tablet leaned against a ceramic cup packed with pens, and a taped-up reminder that read: Make it human, not perfect. She did logos and brochures for restaurants, dentists, the occasional nonprofit—work that kept the light bill honest and her creative muscle limber. The house was small, but the good kind of small; it meant no dream had to shout to be heard.

“Good morning, beautiful,” said a voice that could have sold lullabies at wholesale.

Michelle turned. James came down the stairs buttoning his white coat, the hospital badge clipped at his pocket. He had the kind of face that made people tell him about their childhood pets, and a posture that suggested the world wasn’t going to end on his shift. At St. Mary’s General he was one of the obstetricians families requested by name, the one who could calm a frightened teenager and a furious grandmother in the same room without breaking a sweat.

“You’re wearing the coat at home,” Michelle said. “Are you trying to steal the coffee’s thunder?”

He kissed her forehead and took the mug she offered. “Emergency call might pop. I want to look like I mean it.”

“Will you be late again?”

“Possibility,” he admitted, then softened it with a smile that had gotten them through worse. “But I’ll try to come home early. Caroline and Tom are coming for dinner, right?”

At her sister’s name, Michelle’s shoulders loosened. “They are. She’s eight months and all belly. Walking up the stairs looks like she’s summiting Everest, but she’s so happy, James. Honestly, just looking at her makes me happy.”

The words surprised her with how true they felt. There were hours, sometimes whole days, when the infertility treatments and the calendar and the quiet ache made joy feel like a language she’d forgotten. But loving Caroline—loving the softness that had come over her, the way her hands had adopted their slow, protective choreography—was simple. Even the complicated parts felt like a kind of grace.

James squeezed her hand. “We’ll get our story,” he said. The sentence was worn smooth from use, but it still fit in her palm.

“Today I just want to make her favorite curry,” Michelle said. “And maybe watch Tom try to assemble the stroller without instructions.”

“Now that,” James said, “I will postpone surgery to see.”

They arrived just past six, when the kitchen had warmed the house with spices and the last slant of daylight made the floors look like honey. Caroline came in first, one arm curved under her belly in a gesture that was reverent and practical all at once. Pregnancy had loaned her glow and stolen her ankles, and she appeared resigned to the bargain.

“You look radiant,” Michelle said, folding her into a hug that made room for the newest person in the room.

“The baby is doing somersaults,” Caroline said. “She knows you’re feeding her.”

“She?” Michelle grinned. “New intel?”

“It’s a vibe,” Caroline said, pleased with her own certainty.

Tom followed, steady and tall, the kind of man who made you think of Saturday morning Home Depot runs and remembering the birthdays of nieces you’d never met. He rested a hand on Caroline’s shoulder, and it wasn’t a performance. With Tom, nothing was. Bankers get a bad rap, Michelle thought—not every ledger is about money.

At dinner, conversation orbited the baby because how could it not? James asked if they’d picked names.

“We’re torn,” Caroline said. “Michael if it’s a boy, Emily if it’s a girl. But Tom wants something more unique.”

“Unique is a trap,” Tom said, squeezing her hand. “But ultimately it’s her call. I just lobby for not having to spell it every time we order coffee.”

“Have you finished shopping?” Michelle asked, and saw Caroline’s mouth pinch into a small storm.

“Actually, no,” Caroline confessed. “The crib. The car seat. We don’t know what’s good.”

“Then we’ll go this weekend,” Michelle said, already picturing pastel aisles and miniature socks. “James will come too.”

“Absolutely,” James said. “I’ll be a better doctor if I’ve had to assemble the thing I tell people to use.”

They laughed, because it felt wonderful to be a family that could.

The baby store on Saturday was a democracy of tiny things. Michelle and Caroline moved slowly down the racks of cotton onesies and unaccountably small hats, their hands forming a choreography of lift, feel, fold. Caroline pushed a stroller for a test lap as if she were piloting a rare car. “Sister,” she said, eyes bright. “When this child is born, every day is going to change.”

“It’s scary,” Michelle said. “And exciting.”

“You’ll be a natural,” Michelle added, and meant it. “I’ve watched you with your students. You already are.”

Across the aisle, James and Tom were politely interrogating a clerk about crib safety ratings as though they were vetting a rocket launch. Tom nodded with intense concentration while James demonstrated how not to pinch your fingers, then pinched his finger anyway. They both pretended not to notice.

On the way home, Caroline looked back from the passenger seat to where Michelle sat, her smile soft enough to be a blanket. “Having you here is so reassuring. This child is going to be surrounded by so much love.”

Michelle rested a hand on the shoulder of the sister who’d always been her easiest friend. “Of course,” she said. “Of course.”

By October, the baby shower preparations had turned Michelle’s studio into a factory of joy. She worked the invitations by hand—watercolor background in a not-quite-pink, not-quite-blue that felt like promise, elegant calligraphy that read Welcome, little one with just enough curl to be festive without losing its manners. She showed a mockup to James, who put on reading glasses like a ritual of respect.

“It’s beautiful,” he said, and she could tell by the careful way he said it that he wasn’t just being her husband. “Using both colors is perfect. It’s honest and it’s kind.”

“Caroline insists on the surprise. She says the baby deserves a dramatic entrance.”

“She’s been your sister a long time,” he said. “Drama is her love language.”

They scouted the community center on a Tuesday that smelled like leaves. The room was simple, tall windows facing a garden that was busy with birds and the business of dying well. Michelle walked it like a chessboard, imagining tables here and a gift platform there, and Caroline leaned on her arm and nodded like someone being guided into a dream she trusted.

“Thank you,” Caroline said. “I’ve never had a big party thrown for me.”

“You’ve been a teacher for ten years,” Michelle said. “Every spring is a parade in your honor.”

“That’s different.” Caroline glanced down at her belly. “This one feels… big.”

“Because it is.”

Back home, the guest list grew to thirty—colleagues from the elementary school, neighbors who pretended their dogs were more trouble than they were, relatives with varying degrees of opinions who nonetheless mailed RSVPs with little notes scrawled at the bottom. The cake would be lemon with a crown of sugar-crafted baby shoes because some clichés deserved their reign. Tom volunteered for decorations and returned triumphant with cream and white balloons, a banner that said baby shower in a cursive that almost curtsied, and the bashful look of a man who had asked his wife what she wanted and then bought exactly that.

“You have great taste,” Michelle said, and Tom blushed like someone who’d been seen.

A week before the party they checked the list twice, like responsible Santas. Bottles of sparkling cider and lemonade, tea sandwiches that no one would admit to loving and everyone would eat anyway, prizes for the games that looked like small luxuries—candles and hand creams, soft blankets that whispered about naps not yet scheduled. Caroline moved more slowly now, but her smile had learned the trick of lasting.

On the last shopping trip, Caroline pressed a palm to her belly and laughed. “She’s dancing,” she said. Sarah—best friend since middle school, the person who had once taught Caroline to do eyeliner in a bathroom mirror with a sentence that began, Trust me—put a hand there, marveling.

“Wow,” Sarah said. “She’s really moving.”

“See?” Caroline said, triumphant in a way that made everyone feel like they’d won.

The day before the party, Michelle arrived at the community center at eight with a trunk full of decorations and a head full of errands. Tom and James met her there, and together they became a small moving company. Tables unfolded, chairs marched into tidy rows, the balloon arch trembled toward glory and then held. When they were done, Michelle stood in the doorway and watched the pastel dream breathe the morning light.

“Perfect,” she said.

“Caroline will cry,” Tom said, not unhappily.

“That’s how you know the party is good,” James said. “Cardinal rule of obstetrics and events.”

That night, the four of them sat with their lists one last time. Thirty guests confirmed. Lemon cake ready for pick-up. Games prepped. The big box—the family gift—tucked carefully behind the coat rack.

“Tomorrow,” Caroline whispered, cheeks pinked by excitement. “I can’t believe it.”

“Tomorrow,” Michelle said, squeezing her hand. “It’s going to be the best day.”

“Even my patients are excited,” James said. “I got two knitted booties out of just mentioning it. Neither matches anything, but I respect the hustle.”

Caroline laughed, then grew earnest. “James, after she’s born—would you be her doctor?” It was obvious and not obvious all at once; it was a request to keep the circle close.

“I’d be honored,” he said, and meant it from the marrow.

Late that night, Michelle lay in bed and rehearsed the schedule in her mind—final check at ten, reception at eleven, party at noon—until the numbers melted into sleep. She turned toward James in the dark, tucked her hand into his, and said a sentence that tasted like faith. “When this baby is born, our lives will change too. I feel like… for the better.”

“Then it’s decided,” he murmured, and the decision held.

Morning came clean and blue. Michelle unlocked the community center before the sun had fully flexed, and the room soaked up light as if it had been waiting all week for this shift. Balloons caught the sun and made their own stars. The banner arched above the dais in a quiet bow. Margaret, the manager, poked her head in.

“Special day,” she said. “Your sister’s shower?”

“Whole family operation,” Michelle said, smoothing a tablecloth until the crease surrendered.

At ten-thirty, Tom arrived with flowers. White roses, pale pink gerberas. “She’ll love them,” Michelle said, taking the bouquet and setting it where the light would catch.

Guests trickled in at eleven, bearing packages wrapped in papers chosen for their cuteness tax. Teachers from Caroline’s school arrived in a laughing wave. Neighbors came with casseroles disguised as gifts because comfort is a language that insists on itself. Relatives entered with hugs and the quiet curiosity families carry when they cross town for each other.

“Michelle,” Sarah said, damp-eyed at the threshold. “This is gorgeous. Did you hire people?”

“I am people,” Michelle said, doing a little bow. “We all are.”

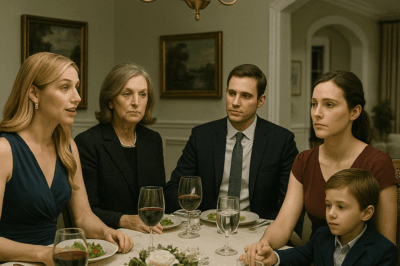

Near noon, the door opened and Caroline came in on Tom’s arm, wearing a sky-blue dress that matched exactly the color that had refused to decide on the invitations. The room applauded. Someone yelled “Surprise!” and someone else shushed them, delighted to be part of the choreography. Caroline stood in the doorway and made the face people make when they are very happy and very loved; she cried, because that’s what good parties are for.

“Thank you,” she said, hands pressed to her chest. “Thank you for making this for us.”

The party lifted and settled into itself. People guessed baby-food flavors and pretended not to be horrified. They matched baby pictures to adult faces with alarming accuracy and learned which uncle had been born with a head of hair that suggested ambition. Caroline sat in her chair and opened gifts with the kind of gratitude that repaid the giver twice. Onesies, bottle sets, a hand-knit blanket that looked like the person who made it had put winter on hold just long enough to finish the border.

“Last one,” Michelle said at one-thirty, rolling out the big box. “From the whole family.”

Caroline’s mouth fell open when she saw the crib parts nested like puzzle pieces in tissue paper. “It’s the one,” she said, voice breaking. “We looked at it. We… I didn’t know…”

“Tom and James are going to assemble it,” Michelle said. “We’re filming the swearing.”

Everyone laughed, easy and uncomplicated as a picnic.

At two, Caroline pressed a hand to her belly and smiled. “She’s been doing this all day,” she said. Sarah asked to feel again, and Caroline guided her hand with the tenderness of someone sharing good news.

“You try,” Caroline said to Michelle. “You’ve done the most.”

Michelle rested her palm against warm fabric and felt the ripple she’d felt all week: life making itself known.

“James,” Caroline called, mischief bright as a ribbon. “Doctor’s opinion?”

He came over, smiling, the white coat a late arrival over his clothes because he’d raced straight from rounds to make it in time. “Do I need a copay?”

“Only if you’re wrong,” Caroline said. “Rates are steep.”

James laughed and placed his hand gently on her belly. He was a man built for reassurance, but as his hand moved—here, then there, then back—Michelle watched his expression shift. Softness drained. A line drew itself between his brows she had only seen on the worst days. His hand returned to the same place and stayed, as if waiting to unhear what it had learned.

“How is it?” Caroline asked, like someone asking how the weather looked ten minutes down the road.

James lifted his hand slowly, as if the air had grown heavier. He stood too fast and reached for Michelle’s arm. “Can we step outside?” he asked, voice low enough that the room kept being a room.

Michelle blinked. “We’re in the middle of—”

“Now,” he said, and it wasn’t a request. It wasn’t even his doctor voice. It was the voice he used precisely never, which is how she knew to go.

She turned to the guests with a smile that belonged to another version of the afternoon. “Be right back,” she said. “Keep drinking the cider.”

“Is there a problem?” Caroline asked, fear arriving in the space concern left behind.

“It’s fine,” Michelle lied, because love is also lying sometimes, and hoping to grow into the truth.

Outside, the parking lot held bright cars and the kind of quiet that comes when everyone you love is indoors together. James spun her toward him by the shoulders, hands gentle, eyes not.

“Call an ambulance,” he said. His voice trembled and then decided not to. “Right now.”

Michelle stared, the sentence not fitting anywhere in the room she’d built in her mind. “What? Why? James, the baby— we felt—”

“That wasn’t the baby,” he said, breath catching on the hard part of the sentence. “Call.”

The world tilted. Her hands knew her phone better than her brain did. She dialed, she heard herself say words like “eight months” and “community center” and “please,” and the operator’s voice was calm like a rope in a flood.

From inside, laughter floated out the door as if nothing had misplaced its own momentum. Michelle doubled over, the asphalt cool under her palms, and the mug of coffee she’d held that morning came to mind—the small warmth you could count on, and how quickly it went cold if you left it too long.

Sirens cut the distance into pieces. Paramedics arrived, gravity in navy uniforms, and James briefed them with the clipped compassion of a man reciting a prayer he would never love. Guests came to the doorway, their smiles falling, packages forgotten. Tom wheeled Caroline out in a chair that somebody found in a utility closet, his face the color of paper.

“What’s wrong?” Caroline asked, panic already half-born. “Why an ambulance? I’m fine. The baby is—she’s—” She reached for Michelle’s hand, and Michelle gave it, because what else is a sister for when the world begins to empty?

“It’s just a precaution,” Michelle said, voice soft as tissue. “We’re going to the hospital and we’re going to make sure everything is okay.”

Tom looked at James. “What’s happening?” he asked, the way a person asks a weatherman to please reconsider the storm.

“We’ll check everything there,” James said. “We’ll take care of her.”

There is a kind of silence that follows sirens, a vacuum the body makes to survive. Michelle rode in the passenger seat of their car behind the ambulance, her hands locked in prayer against a God she didn’t fully believe in and absolutely needed. The lemon cake would sit on the table by the window, sugared shoes perched on top, a sweet skyline in a city that no longer had streets.

At St. Mary’s, Dr. Wilson met them with the face he used for grief soon and maybe. The ultrasound room was bright and unkind. Caroline lay back and whispered to the ceiling, “Baby, we’re here. Mommy’s here.” Michelle stood on one side and Tom on the other, and the machine rendered a map no one knew how to read until they did.

The screen stayed quiet. Dr. Wilson moved the probe like someone sweeping for a signal in a place that had never heard of radio. He clicked a button. He clicked another. He took a breath and turned off the machine.

“Dr. Roberts,” he said, eyes flicking to James with a weight that had nothing to do with hierarchy, “can we speak in the hall?”

They did, but the hallway didn’t change anything. When they returned, Caroline’s eyes searched their faces like they were the last pages of a book and she wanted a better ending.

“Doctor,” she said. “The baby is fine, right?”

Dr. Wilson pulled a chair to the bedside and sat the way good doctors do, making the room smaller so the truth could fit without echo. “Mrs. Mitchell,” he said softly. “I’m so sorry. We cannot confirm a fetal heartbeat.”

Time, obedient until it wasn’t, stepped out of the room. Words untethered from meaning. No heartbeat wandered the air like a phrase in another language.

“The baby has passed away,” Dr. Wilson said, because there are sentences you cannot say with synonyms.

Caroline shook her head. “No. That’s wrong. She was moving. Everyone felt—”

Tom reached for her hand. “Caroline…”

“The examination is wrong,” she said, panic rising like a tide. “The baby is alive. She’s alive.”

Michelle bent and gathered her sister as if the right arms could keep the world on its hinges. “I’m here,” she said, and the words were not enough and they were also everything she had.

Dr. Wilson signaled to a nurse, who brought a file. “Two weeks ago,” he said gently, “you came in after a fall. October first. The notes indicate that the fetal heartbeat could not be found at that time. You were given the findings, but you left.”

“I slipped,” Caroline said, tears starting in tracks she did not consent to. “It wasn’t serious. I… I didn’t—” She looked to Tom, then Michelle, then James, as if one of them could loan her a better memory. “She’s moving,” she insisted, one hand on her belly. “She’s moving.”

“In cases like this,” Dr. Wilson said, voice both physician and human, “the uterus can maintain size for a time. The sensations you’re feeling may be your own muscles, your intestines. I wish it were different.”

The room filled with a silence so complete it seemed to press on the lungs. Caroline looked down and petted her belly like an apology. “I was supposed to be a mother,” she said to no one and to everyone.

“You are,” Michelle cried. “You are her mother.”

Tom folded himself around his wife as if he were trying to be a house. “I should have been there,” he said into her hair. “God, I should have been there.”

James stood near the foot of the bed, doctor and brother-in-law stacked uneasily inside the same man. “You didn’t have to carry this alone,” he said, voice raw. “You never do. We’re family. We do the terrible parts together.”

The nurse slipped out and returned with a quiet woman who introduced herself as the psychiatrist on call, a lifeline in sensible shoes. Words like reality avoidance and grief processing threaded the space, and they did not fix anything, but they made a small path where there had been none.

Later—after the consent forms and the anesthesia, after the surgery that pulled from the world a baby who looked heartbreakingly finished, after the tiny coffin with its bloom of flowers—there would be more parts to this story. Recovery. Winter snow. Counseling rooms. A garden in the spring with forget-me-nots and a marker that said To our beloved child. There would be a boy named Michael who arrived in the fall two years later with a backpack and a brave face and the most important sentence anyone had ever said to Caroline: Thank you for becoming my mom.

But right now, in the bright, unkind room, all that existed was the first cliff and a family deciding, wordlessly and then with words, not to push each other over it.

Michelle sat on the edge of the bed and rubbed circles on her sister’s arm. “We’ll get through this,” she said, voice threaded with all the broken threads, and meant every syllable as a vow. “Together.”

Caroline closed her eyes, and for the first time let the truth sit beside her without fighting to the death. It did not feel like courage. It felt like drowning with a hand in yours.

James wheeled the ultrasound machine gently back into its corner and turned off the light that had made everything too visible. He stood there, one hand on the switch, looking at the family and making a private promise to keep doing the simple thing that makes the hardest thing survivable: show up, and keep showing up, until the dark learns your name.

Part Two: The Long Winter

Grief has a sound if you listen long enough. It’s not a wail—those burn out. It’s not even the sobs that come like hiccups and leave like thieves. Real grief is the radiator knocking in the night, the house settling with a groan, the refrigerator clicking on and off, the small noises of a life that insists on continuing. In the weeks after the baby shower that ended with sirens, Michelle learned the symphony of those sounds and the way each one asked, Are you still here? She was. She made coffee. She watered plants. She folded laundry very neatly because it was a thing that could be made right with her hands.

Caroline stayed at St. Mary’s for three nights. Dr. Wilson kept the room as gentle as a hospital can be—lights low, nurses soft-footed, a small lamp by the bed rather than the overhead glare that makes every problem look insoluble. The psychiatrist, Dr. Shah, visited each day and never rushed, as if time belonged to Caroline until she was ready to loan it back to the world. Michelle came mornings and James came evenings, and Tom came always. He slept in the chair with his shoes on. When the night nurse offered him a blanket, he tried to give it to his wife. “We have two,” the nurse said, with the kind of economy that makes you love nurses more fiercely than most relatives. “One for each of you.”

When Caroline was discharged, winter had staked its claim. Columbus looked the way black-and-white films feel. The maple leaves that had flamed so brilliantly were now lacework on the ground, and the sky had swapped out its paintbox for a single gray crayon. Tom drove them home very carefully, as if the world had become brittle and he was the only one who’d read the instructions. Michelle followed in her car, keeping three lengths back and a prayer forward.

Michelle had spent the previous day at Caroline and Tom’s house doing the kind of frantic kindness that feels like purpose. She stripped the bed and put on clean sheets that smelled like lavender and mercy. She placed a stack of fresh towels in the bathroom and arranged them as if order were a spell. The nursery—soft yellow, animals dancing along the border—she left untouched. She closed the door gently. Some rooms needed to choose for themselves what they wanted to be.

Inside, Caroline went straight to the couch and sat like someone who had remembered gravity. She tucked her feet under a blanket that had somehow learned how to be heavy. Tom hovered. James checked the prescriptions in a small white bag and made sure the instructions were written clearly and then rewrote them anyway because the font was rude. “Call me,” he said, and meant the verb in the old-fashioned way, the way that still works at two in the morning.

“Thank you,” Caroline whispered. Her voice had shrunken to fit the day.

After everyone left, Michelle drove home on streets salt had already argued with. She let herself in and stood in the quiet kitchen. The mug she’d been using for weeks—white with a blue stripe—sat in the dish rack like an anchor at rest. She took it out and set it on the counter and then did not pour coffee because her hands were shaking. James came in just as the tremors became tears. He folded her against him and rocked her without counting. “I know,” he said to the top of her head. “I know.”

Grief made Caroline’s world small. It shrank to the couch, the bathroom, the bedroom, the couch. Dr. Shah explained it to her like an honest map: depression laying its blanket, anxiety rattling the windows, dissociation a helpful thief who pockets time when it gets too heavy. “Your brain is trying to save you,” Dr. Shah said gently. “We’ll help it choose better tools.”

The days were measured in pills and appointments and the reliable arrival of soup that people who love you make. The casseroles came too, a Midwestern chorus—lasagna, baked ziti, tuna noodle with potato chips on top, each a translation of I don’t know what to say but I can keep you fed. Michelle arranged them in the fridge like a calendar and made a spreadsheet because spreadsheets are what you do when the world does not balance.

Sarah visited and didn’t ask questions that required Caroline to be wise. She brought lip balm and the gossip from the school because the world kept being the world even when yours stopped, and sometimes the proof is a principal who misused whom in a newsletter and must be discussed. They sat side by side, shoulder to shoulder. Michelle learned there are friendships that sit in silence like old wood—sturdy, a little creaky, warm when you lean in.

Tom blamed himself. He did it in the car, to the steering wheel; in the shower, to the tile; in the office, to the edge of his desk when no one was looking. He said it out loud once to Dr. Shah when Caroline dozed and Michelle and James had gone to feed the parking meter: “I should have been there. When she fell. When they told her. It’s my job to—” He couldn’t finish the sentence because it had too many duty stations and not enough soldiers.

“Guilt is grief in a costume,” Dr. Shah said, writing it down for him in case he needed to pin it somewhere. “It looks useful because it’s busy. Let’s find the feelings underneath it. They’re less showy, but they don’t burn you to hold.”

He nodded, because she had said the thing he didn’t know how to say: he had been trying to earn a past with present-tense penance. He could not. He could, however, be here in big ways and in small. He started with tea—hot water, honey, not too much lemon. It was a particular alchemy that Caroline could sip without adding a task to her day. It felt like a job he could do, and when she drank from the mug and he saw her throat move, something in him went quiet enough to let a little hope through.

James took the holidays off call as much as a hospital would let him. He said no to Christmas Eve shifts by trading three unlovely weekends in February and a night in March he’d wanted for Michelle’s birthday. “We have to pick our sacrifices on purpose,” he told his residents, who watched him with the disbelief of people not yet old enough to schedule happiness.

He cooked. The man could char a steak, but he also learned to braise short ribs and roast Brussels sprouts with a little maple syrup because life had taught him that bitterness needs sweetness or it just sits in your mouth. He burned the first pan of pecans and swore with such elegance Michelle applauded. “Doctor vocabulary,” she said. “Latin roots, mild cursing.”

They went to Caroline and Tom’s on Christmas afternoon with cinnamon rolls Michelle had coaxed into spirals that rose. Caroline had brushed her hair and put on mascara, tiny rebellions against the gravity of the couch. They exchanged gifts as if the ritual itself could be an incantation. Caroline gave Michelle a scarf she’d knitted in September, the stitches fat with the faith of a woman making a thing for a baby who would borrow pieces of her aunt’s warmth. Michelle wrapped the scarf around her neck and did not cry in the living room. She cried in the bathroom later, quietly, into a towel that did not ask what it had done to deserve it.

When the calendar tipped into January, the snow came in earnest. It erased the edges of everything and made the city look like a drawing before the ink. Dr. Shah increased one medication a little and decreased another and Caroline reported that her brain felt less like a room with all the lights on at once. She began sleeping through the night more often. She woke from nightmares fewer times. The door to the nursery stayed closed, but the closed door stopped feeling like a verdict and started feeling like a boundary, and boundaries, Dr. Shah said, were just doors that had learned to be polite.

Michelle and James found a grief group at the hospital, and they went with Caroline and Tom one Tuesday evening that smelled like coffee and snow boots. The room was a circle of chairs and a tray of cookies no one ate. People said their sentences like recipes, listing ingredients they wished they could return—weeks, names, expectations, the corner crib in an apartment, the secondhand bassinet that had belonged to a cousin and had a dent to prove it. No one tried to fix anything. When it was Caroline’s turn, her voice shook but did not hide.

“At first,” she said, “I couldn’t understand how to be a mother without a baby. Now I think maybe motherhood is part action and part attention. I didn’t get to do the action part. But the attention—” She swallowed—“is still here.” She put a hand on her belly, which had begun to learn absence as its new shape. “It still thinks I should listen.”

A man across the circle nodded so fiercely his glasses slipped down his nose. “My wife says that,” he said. “She says she still listens.”

On the drive home, Tom took the long way. They passed the elementary school where Caroline taught, the playground half-buried, the monkey bars cold and shining. “Do you want to go back in the spring?” he asked, very gently.

“I think so,” she said. “I think the kids will loan me their forward motion.”

“They always do,” he said, and they made a plan under the dome light.

In February, the sun climbed the sky like it remembered how. Caroline started walking with Michelle three afternoons a week around the block—once, then twice, then the small triumph of three laps with a stop to admire a snowman losing half his head with grace. They talked about the unglamorous parts of healing because they were workers and this was a job. “Did you shower?” Michelle would ask, and Caroline would grin and answer, “Gold star. I also ate a sandwich. Two points.” When your victories are small, you are allowed to make the scoring system generous.

Sarah came over on Sundays and they made lesson plans for the spring semester. “You can sit and tell me what to write,” Sarah said, “and we’ll call it professional development.” They built a reading list together—Kate DiCamillo because hope, Jason Reynolds because rhythm, Charlotte’s Web because mercy. Caroline held the spine of each book and let the words remind her that endings had to be earned, and even then, they rarely arrived on time.

Tom went to see the nursery sometimes. He didn’t go in. He leaned his forehead against the door and told the room that he was sorry and that he was also trying not to be, because Dr. Shah had said both could be true. He listened to the silence and then went to make tea.

James and Michelle had their own winter. It was shorter because it wasn’t happening inside their bodies, but it was winter all the same. Sometimes Michelle woke at three a.m. and pressed her palm to the flat of her belly and apologized to the dark. James woke with her because marriage is a relay of insomnias. He would make toast with butter and cinnamon sugar and they would sit at the table eating children’s food like grown-ups who understood that comfort is a nutrient.

One night, Michelle said, “I keep thinking grief is like my design proofs. I want to get it approved. I keep revising, thinking if I find the right words or the right amount of tears, someone will sign off, and we can go to print.”

“And?” James asked, patient as a porch light.

“And there is no client,” she said. “There’s just time.”

He reached for her hand. “Time is the worst client. It never responds to emails.”

She laughed, a sound she almost didn’t recognize because it didn’t have the usual carburetor of pain. She let it run anyway.

March made a brave noise. The snow melted into reluctant puddles that children jumped over with the concentration of Olympic sport. Caroline increased her sessions with Dr. Shah to once a week and then learned she didn’t need to plan what to say. The words arrived like birds on a fence. Some days they just sat and watched them until they flew off.

One afternoon, Caroline said, “When I fell down the stairs, I told myself it was nothing. And when the doctor told me… I decided he was wrong. It was like I stepped into a hallway and closed the door behind me. It was nice in there. Quiet. No one could reach me.”

Dr. Shah nodded. “Hallways keep us from the fire. They also keep us from the exit. Coming out is an act of courage. Staying out is an act of maintenance.”

Caroline smiled, small but present. “I have always been good at maintenance.”

“I know,” Dr. Shah said. “You were a mother longer than your memories give you credit for.”

On another day, Caroline asked about future tense verbs. “Do I get to say will again?” she asked. “Or am I stuck with was and am?”

“Try ‘can,’” Dr. Shah said. “It doesn’t promise the world. It promises your participation in it.”

April brought the soft insistence of green. Michelle spent a Saturday in the narrow strip of earth behind Caroline and Tom’s place, her knees damp through her jeans, hands deep in soil that smelled like clean history. She planted forget-me-nots along the fence line and a small oval of violets around a smooth stone James had salvaged from the hospital’s old front steps before the renovation. On the stone, Michelle had stenciled, in a hand steadier than she felt: To our beloved child.

When she stepped back, Caroline came out onto the porch. She wore a sweater too big and a face that had learned restraint. “It’s beautiful,” she said. “What are the tall ones?”

“Larkspur,” Michelle said. “They’re fussy but honest.”

“And these?”

“Forget-me-nots. They reproduce like rumors. That’s the plan.”

Caroline knelt, touched the stone, and then, without drama—perhaps because drama had earned its rest—she spoke. “Thank you, baby,” she said. “It was a short time, but you were here. I won’t ever pretend you weren’t.”

They sat on the steps and drank lemonade in glass bottles like teenagers who had earned the right to be ordinary again.

Tom came out with three cookies and announced, “I think I have invented the world’s worst snickerdoodle,” which made Caroline laugh so hard she choked and then cry because that’s how the body sometimes says thank you.

In May, the principal at the elementary school sent Caroline a card the size of a legal pad. Inside, the third graders had written notes that favored exclamation points over grammar. Dear Ms. Mitchell, we miss your stories!!! Dear Ms. Mitchell, I can do fractions now because you taught me to break pizza. Dear Ms. Mitchell, come back soon unless you need more time then take more time but still come back. Caroline pressed the card to her chest and closed her eyes. “They will loan me their forward motion,” she said again, as if reminding herself to believe her earlier self.

She returned to the classroom in June for the last three weeks of school. It felt like merging onto a highway from a full stop, but the kids made room. On the second day, a student named Aaliyah raised her hand and said, “I’m sorry your baby died,” with the clarity of a child who has not yet learned to fear nouns. Caroline thanked her and said, “Me too,” and then Aaliyah asked if they could still do read-alouds after recess. “We can,” Caroline said. “We absolutely can.”

At home, the nursery door opened for the first time. Not all the way, not with a reveal, just enough to let air in. Caroline stood there with Tom and held his hand and said, “We can repaint.” He said, “We can wait.” They decided to wash the curtains. It felt like diplomacy; it felt like progress.

Summer turned the air to honey. Caroline and Tom took small trips—an overnight to a bed-and-breakfast in Granville where the innkeeper recognized their sadness and asked if they wanted breakfast in the room. They said yes and ate pancakes propped up by pillows, and when Tom spilled syrup on the sheet, Caroline said, “We’re those guests,” and they laughed into the kind of giggles that close the gap between two people like a zipper.

Michelle and James went too far on a hike because they trusted the map more than their legs and wound up sitting on a rock sharing a granola bar like survivors of an expedition. “We are not as young as Instagram thinks we are,” James said, massaging a calf that had written a letter of resignation. Michelle tucked her head on his shoulder. “We’re still here,” she said. He kissed her hair. “We’re still here.”

They talked, sometimes, about babies and about not-babies. About trying again, about not trying, about adoption, about a life where their house held them and their work and their friends and their nieces and nephews and their godchildren and their students and their patients and that might be a family too. Each conversation ended not with a verdict but with the understanding that the story was ongoing and they were committed to not pretending otherwise.

In late August, Caroline brought up adoption as if it were a word she’d been carrying in her pocket for a while and wanted to see if it looked different in the light. They were on Michelle’s back porch eating tomatoes that tasted like the sun’s autograph. “I’ve been thinking,” she said. “About becoming a mother again. In a different tense.”

Michelle put down her fork. “Say more.”

“I work with kids all day,” Caroline said. “Every single one arrives with a past and a future and a backpack that’s heavier than it looks. I keep thinking about how love is attention, and I don’t need a baby to give it. I need a human.”

Tom joined them with a bowl of peaches. “I’ve been thinking it too,” he said, a little bashful in the way men get when they open a door and are relieved it doesn’t slam. “I talked to Dr. Shah. She said grief and love can be teammates if we let them take turns.”

“I think we should adopt,” Caroline said, the words steady now that they’d been aired. “I think our house is ready to be a house again.”

Michelle felt that familiar tightness in her chest that was half joy and half the ache that joy requires as down payment. “You’ll be extraordinary,” she said, and it wasn’t the cheerleading kind of compliment. It was the statement of someone who had watched this woman show up for small people with a patience that made time behave.

James, who had come outside with a pitcher of sweet tea and the medicinal belief that sugar can carry decisions safely across a table, nodded. “There are a lot of ways to be born,” he said. “Some of them happen on paper first.”

They researched agencies with the fervor of people shopping for a parachute and the patience of people who had learned to distrust speed. They filled out forms that asked questions both obvious and insolent. They read about trauma in children’s bodies and about the way love looks different when someone has learned to expect its absence. They took the classes, watched the videos, learned the acronyms, met other couples in the fluorescent rooms where possibilities are briefed. They made a book about themselves—photos of the house, of the park, of Thanksgiving with Michelle’s parents, of Tom holding a niece like he’d invented the concept, of Caroline in her classroom with a reading crown the kids insisted she wear. In the captions, they were honest: We are funny on Tuesdays and tired on Thursdays. We fight about the dishwasher and say sorry before bed. We will not be perfect, but we will be here.

That fall, something like fate and something like paperwork and something like the stubborn insistence of hope brought a five-year-old boy named Michael into their living room. He had eyes that took an inventory of the world and hands that gripped the arm of the couch like a sailor unsure about land. The caseworker introduced him and then did the tactical retreat that good caseworkers do to see how oxygen moves between strangers.

“Hi,” Caroline said, and it was the same voice she used for scared nine-year-olds on the first day of school. “I’m Caroline.”

“Tom,” Tom said, kneeling so they were eye level.

“Michael,” the boy said, as if testing whether the word belonged to him.

“Would you like lemonade?” Caroline asked. “It’s the good kind. Yellow.”

Michael nodded and looked around as if the walls might lunge. He sipped. He held the glass with both hands. He put it down very carefully on a coaster because someone had once told him about protecting furniture and he had learned to obey the rules that were clear.

At dinner—spaghetti because that is the universal solvent—Michael twirled his fork slowly and then said, as if filing a report, “The sauce is not spicy.”

“We can fix that,” Tom said solemnly, reaching for the shaker of red pepper flakes and then stopping, performing a pantomime of restraint that made Michael giggle.

Before bed, Caroline showed Michael the room that had been a nursery and then a closed door and then a lesson in paint. Now it was just a small, soft room with a bed with a quilt that had learned patience, a bookshelf with gaps because you’re not supposed to finish everything, and a nightlight that looked like a moon with a dimmer switch.

Michael put his backpack on the floor as if worried it might go missing. He looked at the bed, then at Caroline. “Is it okay if I sleep under the covers?” he asked, and something in Caroline’s chest both cracked and mended at once. “It is,” she said. “That’s exactly what they’re for.”

He climbed in. He looked so small in a bed that had been waiting so long. He stared at the ceiling for a minute, as if making sure it would not do anything surprising. Then he turned his face toward Caroline and, in a voice that no one had a right to yet and that he gave anyway, said, “Thank you for becoming my mom.”

Caroline sat on the edge of the bed and smoothed his hair like it was a book she loved. “Thank you for becoming my son,” she said. Tom stood in the doorway with a throat that had lost the knack of swallowing. The caseworker sat in her car out front and wrote, They’re ready.

Michelle and James came over the next day with a stuffed bear that had seen some things and a stack of picture books that had helped a lot of children. Michelle watched Michael and felt the sharp tug that children can surprise you with when they walk into your life and rearrange the furniture in your heart without getting permission. James taught him how to make pancakes shaped like letters, and Michael asked for M and then giggled because it was his letter and so was the word mom.

That night, after the house had gone quiet and the nightlight did its small lunar work, Michelle sat in her own kitchen and allowed herself a cry that was joy flavored with relief. “They made it through the winter,” she said, and James, who had watched a lot of winters from a lot of delivery rooms and seen a lot of springs follow, said, “They did.”

Michelle looked out the window at a street that had learned its colors again. “We did, too,” she added, and let the truth land where it needed to.

By the time the leaves turned that next year, the family had recalibrated. Time had not healed all wounds. It had given them scar tissue, which is not the same as the original skin and not worse either—just proof of repair. Caroline returned to her classroom full-time and learned which kids liked which kinds of attention. Tom stopped apologizing to the air and saved his sorries for when they mattered. Michael started soccer, where he ran in the untidy way five-year-olds do and loved oranges at halftime like they were a religion. On a crisp Saturday, he scored a goal by accident and then celebrated like he’d invented physics. Caroline and Tom laughed like people in a commercial for joy.

On the drive home, Michael—still in shin guards, still sticky with the cocktail of sweat and triumph—announced, “When I am big, I am going to be a dad who cuts the crusts off sandwiches.”

“You can be any kind of dad,” Tom said. “Crust-removing is an advanced skill.”

“You can also be an astronaut,” Caroline added. “Or a librarian. Or a person who makes park benches exactly the right height.” The list was ridiculous on purpose. Michael nodded as if she had just assigned him very important homework.

At Thanksgiving, they all gathered around the table, and the litany of gratitude included the usual suspects—health, jobs, pie—and the new: a boy who liked the nightlight, a garden that had learned to bloom as a reminder rather than a command, a couch that had held a family through a season of necessary stillness. After dinner, they stood at the back fence and looked at the forget-me-nots, now brown and brittle, holding their shape under the first whisper of frost. “They’ll be back,” Michelle said. “They don’t know how to quit.”

Caroline slipped her hand into Tom’s. “Neither do we,” she said.

Michelle tucked her arm through James’s. “Neither do we,” she echoed, and for once the repetition felt like an improvement rather than a draft.

The winter that followed was still winter. There were days when the sky sat heavy and refused to hand over a single blue square. There were afternoons when Michael came home sullen because a kid at school had called him foster like an insult they’d heard misused. Caroline wrote the teacher an email that began with Hello and ended with Thank you and contained a spine in between. Tom read a book called The Connected Child and understood for the first time that the tantrum wasn’t about the juice. Michelle and James went to a fertility appointment in January and came home with the kind of tired that lived behind their eyes. They ate the emergency brownies from the back of the freezer and watched The Great British Bake Off because kindness has an accent sometimes, and it helps.

But there were bright spots, and they were brighter for being stubborn. Michael lost his first tooth and insisted on writing a note to the tooth fairy explaining that the tooth was small but brave. Caroline received a Valentine from a student that said, U R the best teacher because you smell like markers and books. Tom taught Michael how to fold dollar bills into little shirts. Michelle landed a design contract with the city parks department and spent a month drawing leaves like a college student in love. James delivered a baby in an elevator when the world refused to follow hospital layout, and the father cried and then hugged James and put his phone number in his hand like a talisman. “Come to the barbecue,” the man said. “Doctors need ribs, too.”

They went to the barbecue. Michael tried three sauces and pronounced two acceptable. The man who had handed over the address slapped James on the back like a cousin. “Elevator Dad,” James said by way of introduction. “Elevator Doctor,” the man said back, as if these were the only degrees that mattered.

By spring, the forget-me-nots returned as promised, audacious and blue. Caroline knelt beside them with Michael and told him about a baby who had been here for a short time and left an impression that took up permanent residence. Michael listened, serious as a contract. “Do I have to be sad?” he asked, because children are the gift of literal questions.

“You get to be whatever you are,” Caroline said. “I’m sad and I’m happy.”

“I’m hungry,” Michael decided, and Caroline laughed into the cholera of relief that comes from telling the truth and being received by a five-year-old.

Michelle watched from the back steps, the stone warm under her palms, and thought about the sentence she had taped above her desk: Make it human, not perfect. She was starting to believe it had been advice for life, not logos.

James came out with popsicles because it was officially warm enough to pretend it was summer. He handed one to Caroline and one to Michael and ate his own too fast because he wanted the bright cold. He made a face when the brain freeze hit and Michael laughed and said, “Doctor, you are supposed to know better.” James nodded gravely. “Experience is the thing that lets you recognize your mistakes the second time.”

Michelle took a picture in her mind: the three of them, the flowers, the stone, the way light found all the edges and softened none of them, and still—it was beautiful.

On the last night of school, Caroline stood in her classroom under the hum of fluorescent lights that had watched a hundred bulletin boards go up and come down. She collected the last of the glue sticks and straightened the tub of unsharpened pencils and took down the calendar. She ran a hand over the reading rug as if to thank it for forgiving accidents. She turned off the lights and closed the door and allowed herself a moment in the hallway to feel the weight of the year and the way she had carried it.

Tom was waiting in the parking lot with the windows down and Michael in the back seat with a drawing he insisted was a portrait of all of them at once. It looked like a comet with legs. “We are handsome,” Tom said.

At home, Michelle and James were waiting with takeout from the place that loved cilantro more than the law allowed. They ate on the porch. Fireflies practiced their punctuation in the yard. Michael turned the porch steps into a stage and performed a song that was half made-up words and half phonics. Caroline leaned against Tom and felt the absence beside her like a person they had made room for. It didn’t hurt less for noticing. It hurt more honestly.

When the dishes were done and the porch had absorbed their laughter, James said, “We should plan a trip.”

“Like a beach?” Michelle asked.

“Like anywhere with a horizon,” he said. “It’s been a year since the shower. I want us to look at a line that keeps going.”

Caroline smiled. “Put that in one of your discharge notes,” she said. “Prescription: horizon.”

He pulled out his phone obediently and typed it into his notes app, because sometimes the best medicine is the sentence you remember to say at the right time.

By the end of that long winter and longer spring, the family had learned a trick that looked small and was not: how to end a day. They had been ending days their whole lives, but this was different. They stopped waiting to feel finished. They stopped expecting resolution. They did the dishes and turned off the lights and folded into each other on couches and in doorways and at the top of stairs and said, “Today was a lot,” or “Today was enough,” or simply “Today,” and let the period do its tiny work.

On a June night sweet with cut grass, Caroline stood in the doorway of Michael’s room and watched him sleep, his mouth open, his small body doing the serious work of resting. Tom came up behind her and put his chin on her shoulder the way he did when he wanted to be there without adding weight. “We made it,” he whispered into her hair.

“We did,” she said.

Across town, Michelle and James lay on their bed in the cool dim, the ceiling fan making lazy decisions. “We are still writing,” Michelle said, half-asleep. “Even on the days I think we’ve lost the plot.”

James tapped a finger on her hand like a metronome. “The plot is overrated,” he said. “This is character development.”

She snorted a laugh. “You’re not allowed to be funnier than me.”

“Occupational hazard,” he murmured, and fell asleep.

The house—both houses—made the quiet noises of a life continuing. The radiator knocked. The refrigerator clicked. Somewhere, a neighbor’s dog barked at a squirrel who had a meeting to get to. The maples outside prepared their leaves for another round of show-off season. The garden held its blue like a secret it was dying to tell.

And the family—no longer provisional, no longer theoretical—did what families do when they have weathered a storm and refused to evacuate: they slept, they woke, they kept each other. Which, Michelle thought as she drifted, is the most dramatic thing most of us will ever do, and the most important.

Part Three: Blueprints for a New House

Families are not built in a day. They are built in Tuesday afternoons when the grocery store is out of the good peanut butter, in Thursday evenings when the dishwasher refuses to cooperate, in Saturday mornings when someone decides pajamas are acceptable until noon. Caroline and Tom learned this truth in real time with Michael, and Michelle and James found themselves pulled into the renovation too, sketching the blueprints of what a “real family” might look like when you accept it doesn’t have to match the catalog.

The Arrival That Stuck

Michael was five the autumn he came. He arrived with a backpack too big for his shoulders and a look in his eyes that said he’d memorized exits. The caseworker left after a polite hour, promising to check in but knowing instinctively this house had already passed its inspection the moment Caroline crouched down to eye level and offered him lemonade.

That night, Michael didn’t cry. He didn’t speak much either. He tested the bed like a scientist, ran his hand along the quilt as if it might report back to someone, and finally crawled under the covers with his shoes still on. Caroline sat in the doorway for a long time, humming the off-key lullaby she used for her students during indoor recess when the rain was mean. At midnight, she returned with Tom to find Michael asleep, shoes on the floor, quilt tucked around him like trust practicing for permanence.

The next morning he padded into the kitchen where Tom was burning toast with an enthusiasm that outstripped his skill. “Do you eat cereal?” Tom asked.

“Sometimes,” Michael said. It was the first full sentence he’d offered.

“We have cornflakes,” Tom said, as if offering diamonds.

Michael shrugged, but when the bowl hit the table, he ate every bite and drained the milk. Caroline blinked back tears because sometimes family is born between spoonfuls.

Aunt and Uncle in Practice

Michelle and James became Aunt and Uncle on a Tuesday, without ceremony but with fanfare nonetheless. They brought a bear missing one button eye and a stack of books chosen with a librarian’s care. Michelle taught Michael how to draw bubble letters, and James showed him how to pour pancake batter into the shape of an “M.”

“Is that for Michael or for Mom?” Michelle teased.

“Both,” James said, flipping the pancake with unnecessary flourish. “That’s called efficiency.”

Michael giggled, syrup dripping down his chin. “Doctors are funny,” he declared. James bowed.

From that morning on, Michael called them Aunt Shell and Uncle J, which stuck faster than syrup to the counter.

The Nursery Rewritten

The room that had been painted yellow years ago became Michael’s within weeks. The crib was long gone, replaced by a sturdy twin bed. Caroline and Tom let Michael choose a new color for the walls, expecting something wild. He picked sky blue.

“Why blue?” Caroline asked, curious.

Michael shrugged. “It looks like outside.”

So Tom painted, Caroline taped, and Michelle showed up with stencils of stars. James contributed by holding the ladder and reminding everyone not to break bones in the pursuit of whimsy. By the end of the weekend, Michael’s room looked like a place that wanted him.

When he walked in, he said simply, “It’s mine.” And that was all the confirmation they needed.

Setbacks and Firsts

Not every day was smooth. Michael tested boundaries, sometimes with silence, sometimes with tantrums so loud the neighbors probably learned his middle name. He hoarded snacks under his bed, as if cupboards were a fleeting promise. Once he bit a classmate over a Lego dispute, and Caroline received the phone call in the middle of a math lesson. She handled it with the calm of someone who had refereed playground arguments for a decade, but later in the car, she gripped the steering wheel until her knuckles turned white.

“He’s scared,” Tom reminded her. “Not bad. Just scared.”

Still, the first time Michael called her “Mom” without prompting, it landed like a medal she hadn’t applied for but desperately wanted. They were brushing teeth in the bathroom. Foam around his mouth, Michael said, “Mom, can I have the blue toothbrush next time?” Caroline froze, toothbrush midair, and Tom nearly cried in the hallway.

Parallel Blueprints

Meanwhile, Michelle and James were drafting their own plans, though theirs were less tangible. After years of fertility treatments, their conversations shifted. Some nights they still scrolled through forums, whispering about possibilities. Other nights they sat in silence, eating brownies from the pan, acknowledging the ache without needing to solve it.

Michelle watched Caroline with Michael and felt something like envy but softer—like looking at a painting you love but don’t need to own. She designed logos by day and wondered if maybe family could be broader, messier, chosen.

One evening, James poured wine and said, “What if our future doesn’t look like the one we thought?”

Michelle sighed. “Then we design a new one. I do that for clients all the time.”

He smiled. “Blueprints for a new house.”

Laughter in the Cracks

By Christmas, laughter had begun to echo in the cracks where grief once lived. Michael discovered the joy of sledding, shrieking down a hill while Tom sprinted after him in comic futility. Caroline taught him to bake cookies, though half the dough mysteriously vanished. Michelle gave him a sketchbook, and James supplied an endless stream of dinosaur facts.

On Christmas Eve, they all gathered—two couples, one boy, and a table groaning with food. Michael insisted on saying grace. “Thank you for my bed, for pancakes, for crayons, for snow, and for everybody here.”

No one corrected him. No one added a word.

Winter into Spring

Winter surrendered reluctantly, but by March the maples were fat with buds. The forget-me-nots in Caroline’s garden returned, stubborn and blue. Michael knelt beside them, running his small fingers along the petals.

“What are these for?” he asked.

Caroline swallowed hard. “They help us remember someone important.”

“Do I have to be sad?” Michael asked plainly.

Caroline smiled through tears. “You get to be however you feel. I’m a little sad, but I’m happy too.”

Michael thought for a moment, then announced, “I’m hungry.” Caroline laughed, kissed his hair, and decided that was the most honest prayer she’d ever heard.

The New Normal

By summer, normal looked different but right. Caroline returned to teaching, Tom perfected crustless sandwiches, Michael started soccer and lost his first tooth. Michelle signed a big design contract and realized her studio no longer felt small—it felt enough. James delivered a baby in an elevator and came home smelling like adrenaline and gratitude.

On the porch one evening, fireflies flickering, Caroline said, “At first, I thought the world had ended. But it wasn’t the end. It was a new beginning.”

Michelle nodded, holding James’s hand. “Family isn’t about keeping sorrow out. It’s about holding each other up when it comes in.”

Tom raised his glass of lemonade. “To blueprints that change.”

Michael clinked his plastic cup against theirs. “To pancakes shaped like M’s.”

Everyone laughed, because sometimes the clearest endings are the ones that sound like beginnings.

Part Four: The Long Horizon

Horizons aren’t fixed; they move with you. The family learned this slowly, the way you learn to trust new shoes—step by step, until one day you realize they’ve molded to your stride. By the time Michael turned seven, the house that once held grief like an unwelcome tenant now carried laughter in its rafters.

The Garden in Bloom

The forget-me-nots returned each spring without fail, a stubborn covenant. Caroline taught Michael to water them gently, “like you’re whispering.” One day he asked if he could plant something new beside them.

“What would you like?” she asked.

“Sunflowers,” he said. “So the little blue ones don’t get lonely.”

Tom bought seeds the next morning, and by July, a line of tall, gawky sunflowers leaned along the fence like cheerful bodyguards. Caroline stood with Michelle one evening, the flowers golden against the dusk.

“Funny,” Caroline murmured. “At one time, that patch of earth felt like a grave. Now it looks like a choir.”

Michelle squeezed her hand. “Grief doesn’t go away. It just learns harmony.”

School Days

School suited Michael. He became the kind of kid who collected facts and distributed them freely. At eight, he declared to his third-grade class that the fastest land animal wasn’t the cheetah—it was “my mom when she’s late for work.” Caroline laughed until she cried when the teacher sent home the anecdote on a sticky note.

But school also came with shadows. A boy on the playground once sneered, “You’re not even their real kid.” Michael came home fuming, fists clenched.

Caroline sat on the porch steps with him. “What did you say back?”

“I said, ‘Families are real when they’re real to you.’ Then I kicked the soccer ball so hard it went over the fence.”

Caroline pulled him close. “That’s a better answer than I would’ve found at your age.”

Parallel Paths

Meanwhile, Michelle and James settled into their own rhythm. They stopped charting calendars and learned to measure time differently—by projects finished, by dinners shared, by the quiet miracle of mornings when they woke up on the same schedule.

One evening, Michelle said, “Do you ever feel like we’re missing something?”

James thought, then shook his head. “I think we just have a different syllabus.”

She laughed. “Trust you to put it in academic terms.”

“I mean it,” he said. “We’re the aunt and uncle who show up, who never miss birthdays, who take the kids to museums and feed them ice cream for lunch. That’s a role. That’s a family.”

Michelle leaned her head on his shoulder. “Blueprints, remember?”

“Remember,” he echoed.

The Christmas Revelation

Two years later, Christmas found them all crowded into Caroline and Tom’s living room, Michael nearly ten and trying to act cooler than he was. He tore into a soccer jersey and tried not to smile too wide.

After dinner, Caroline stood by the tree, lights winking across her face. She lifted her glass. “At one time, I thought the world had ended.” Her voice caught, then steadied. “But it wasn’t the end. It was a different beginning. This—” she gestured to Michael sprawled on the floor, Tom adjusting the tree skirt, Michelle and James on the couch—“this is proof.”

Michael looked up from his pile of wrapping paper. “Can we toast with cocoa instead of wine? It’s better.”

Everyone laughed, but they did it—mugs clinking, whipped cream moustaches becoming the family’s unofficial coat of arms.

Horizons

Years passed the way they always do: messy, quick, relentless, generous. Michael grew into a teenager with too-long legs and a grin that still carried the shy five-year-old who once asked if he could sleep under the covers. Caroline and Tom kept teaching him—patience, boundaries, how to apologize without excuses. Michelle and James kept showing up—at soccer games, at art shows, at the hospital when James snuck Michael into the staff lounge for hot chocolate that tasted illicit and wonderful.

And through it all, the family learned a final truth: the horizon is never where you thought it would be, but it’s always there, waiting for you to walk toward it.

Final Gathering

On a clear evening in early winter, the entire family gathered again, this time around Michelle and James’s table. Snow drifted outside like confetti. Dinner was messy and loud. Michael—twelve now, confident, funny—performed impressions of his teachers. Caroline rolled her eyes, Tom nearly choked on his drink, and Michelle laughed until her cheeks hurt.

When dessert came—Michelle’s lemon cake, a nod to a day long ago—Caroline raised her fork. “To family,” she said.

Tom added, “To beginnings we didn’t see coming.”

James lifted his glass. “To blueprints rewritten.”

And Michael, with a grin, chimed in: “To pancakes shaped like M’s.”

They clinked their glasses, their mugs, whatever they held. The laughter that followed was not forced, not borrowed—it was earned.

The Clear Ending

Outside, the snow kept falling, erasing old tracks and making the street look untouched. Inside, the house glowed with warmth, stories, and the sound of a family that had chosen—again and again—to keep walking toward each other.

The horizon, Michelle realized, wasn’t an end at all. It was simply the line where love kept meeting tomorrow.

News

My parents and sister pushed me and my 6-year-old son off a cliff.

Part One: The Hike Willowbrook, Ohio was the sort of town that made postcards feel like they’d been eavesdropping. Spring…

At my sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me, calling me a single mother and a used product…

Part One: Numbers and Shadows The sound of calculator keys echoed in Aaron Johnson’s small home office like a quiet…

My mother-in-law sent me chocolate for my birthday, but my husband ate all of it…

Part One: The Birthday Box The heat in Boston didn’t knock; it moved in and asked what was for dinner….

James Corden Returns to U.S. Late-Night — And He’s Joining Former Rival Seth Meyers

After more than a year away from American late-night TV, James Corden is making his comeback. The former Late Late…

Greg Gutfeld Says Late Night Ignored Viewers — and He Cashed In: ‘There Was Free Money on the Table

Greg Gutfeld has never shied away from stirring the pot. The Fox News personality turned late-night disruptor is once again…

Stephen Colbert Immortalized in Funko Pop as The Late Show Celebrates 10th Anniversary

After nearly a decade of sharp monologues, viral sketches, and cultural commentary, Stephen Colbert is about to celebrate ten years…

End of content

No more pages to load