Part One: The Hike

Willowbrook, Ohio was the sort of town that made postcards feel like they’d been eavesdropping. Spring came with a softened edge, summer with a steady hum, fall with a choir of maples, and winter with a down blanket and an opinion about tires. People here measured time by the festival calendar and the school board meetings, which meant the seasons were always on time even if the buses weren’t. You could drive through in seven minutes or live here for seventy years and never finish waving.

Mary Wilson liked the way the town breathed. She liked the smell of disinfectant and coffee on the hospital’s day shift, the way the monitors bleeped like a polite alarm, the way she could read a pulse with two fingers and a promise. She liked the small rituals: her son’s milk cup lined up on the counter, the chirp of her car at night under the blue-rimmed streetlights, the little magnetic clip on the fridge where Aiden’s art went to become important.

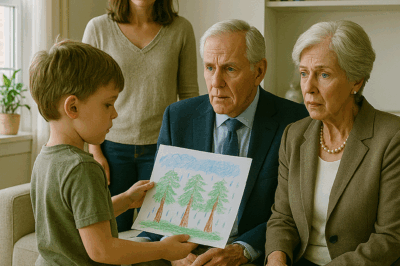

“Mom, look. I drew this at school,” Aiden announced one Tuesday, presenting a page dense with crayon logic: a dog with heroic eyebrows, a cat shaped like a wise loaf, a square house topped with the sort of triangle roofs draw when they’re feeling literal, and three stick figures holding hands: a tall man, a medium woman, a small boy with hair like an exclamation point.

Mary pinned it up with the solemnity of state business. “That’s a great dog,” she said, and petted it to seal the compliment. “Dad will be so happy when he sees it.”

She meant it reflexively, and then felt the reflex brush up against the last six months and go quiet. Thomas had been living in the key of later: later dinners, later nights, later texts, later “work.” Construction ran on deadlines and weather; there’s only so much you can accuse a man of when the forecast got opinionated. Still. Silence has a flavor. Aiden had noticed the busyness, too. Kids are the world’s best lie detectors and the world’s worst judges of what to do with the information.

Thomas came home that night with sawdust on his collar and something unreadable behind his eyes. He ruffled Aiden’s hair, kissed Mary on the cheek, and said the sentence you say when you want to step over something without looking at it: “Long day.”

“Those are trendy,” Mary said lightly, pouring him water and trying not to inventory how he didn’t look at the refrigerator gallery. He drank like he’d forgotten how good water could be.

Her parents lived ten minutes away, in a ranch house with alma mater flags and a front yard that had opinions about edging. Robert and Helen Carter came from the old school of parents who believed in sliced fruit and moral clarity and made both feel like a multivitamin. They’d doted on Aiden, and Aiden had doted back with the fervor of a grandchild convinced Grandma invented cookies.

Linda, Mary’s sister, circulated in and out of town like a comet—flashy, loud, with a career in Columbus that demanded blazers in defiant colors and an Instagram that made furniture look like a dating app. At family dinners, she draped catalogs across the table and talked at a clip. “What do you think of this kid’s chair? It’s ergonomic, it’s sustainable, it’s—” (she lowered her voice as if admitting to a vice) “—actually comfortable.”

Mary thought she saw Linda give Thomas a look that lasted a beat too long, the sort of look that can be explained by lighting, by angle, by paranoia. She scolded herself. Suspicion is a hungry pet—feed it and it grows. She buttered a roll instead.

That night, after pie and the ritual of “Let Grandpa read the book or the earth will crumble,” Mary noticed something she didn’t like and didn’t know how to name: the way Linda looked at Aiden not like a boy but like a variable. The glance was quick and gone, replaced by a smile that showed more teeth than warmth. Mary told herself she was tired. Tiredness will autograph any anxiety if you hand it a pen.

The following week, her father called with a plan he’d sell as impromptu even if it had a spreadsheet: “Hiking on Saturday,” Robert said. “The weather’s going to be perfect and your mother wants a photo with a tree that looks like it’s been through something.” In the background, Helen’s voice did that cheerful echo. “Linda will be there. It’s been too long since we all did something together!”

Mary’s mind did the math: Aiden loved the woods, Thomas had been inventorying his weekends like a CFO, and Mary herself could use the kind of quiet that comes with trail dust. “We’ll be there,” she said, then braced for Thomas’s usual: I have to work.

Surprise: he said yes. He even said it like he meant it. “A hike sounds good,” he told Aiden, who punched the air as if trees needed to be told. But Friday evening, Thomas called at six with a voice the exact shade of Sorry. “Emergency at the site. The inspector flagged the footings. I have to be there tomorrow.”

Mary closed her eyes and did the small accounting of disappointment. “We’ll go,” she said, because telling Aiden no would feel like lying about weather. She hung up, put her hand on the lunchbox she’d already half-packed, and decided to carry both the sandwich and the day.

Saturday blew the sky wide open. In the kitchen light, Mary prepped like a nurse—because she was one. Sandwiches, apples, water, a small first aid kit, wipes, a roll of gauze, vitamin optimism. Aiden came downstairs in his small jacket and hat, eyes wide with a science fair in mind. “I brought my magnifying glass,” he announced. “I’m going to observe insects.”

“My favorite scientist,” Mary said, bending to tie his shoe. She had the odd thought—quick and incorrect—that they were a painting. Happy mother, excited child, Ohio morning, fridge art with a future that assumed an audience. The doorbell spared her the indulgence.

Her parents’ SUV idled outside, practically wagging its antenna. Robert waved like he’d just invented the concept of Saturdays. Helen smiled through the passenger window with a brightness you’d put in the dishwasher. In the back seat, Linda scrolled her phone like it owed her money, dressed in expensive boots and a jacket that looked like it knew a rooftop bar better than mud.

“Wonderful weather,” Robert boomed as he helped Aiden into his booster.

“Perfect,” Helen chimed, as if weather had RSVP’d early. “Today’s a special day.”

Mary filed the phrase into a mental folder labeled Okay Then. She noticed the light packing—no daypacks besides her own, no layers tied around waists, just smiles and a confidence that felt like posture. Linda slid the phone into her coat and gave Mary a look that didn’t match her mouth. “So Thomas couldn’t make it after all,” she said, as if rehearsing.

“Urgent work,” Mary said. “He was disappointed.”

“Yes,” Linda said, quick. “Can’t be helped.”

Robert drove like he was out to impress the mountain. They passed the main trailhead, then the second, then a third path Mary knew for its easy loop and clean bathrooms. The road narrowed, gravel shouldering up to a line of oaks that looked like they had thoughts. Robert turned down a rutted spur that snaked into an area Mary didn’t recognize.

“Dad?” she asked. “Where are we going?”

“Found us a secret route,” Robert said, avuncular and pleased. “Tourists never find this one. The view’s incredible.” He and Helen exchanged a brief glance in the rearview mirror. The signal wasn’t obvious; Mary caught it anyway. Her stomach shifted a quarter inch to the left.

They parked in a bare scrape of ground framed by trees and absence. No other cars. No other voices. Silence is fine until you notice it won’t introduce itself.

They got out. The air had that new coin shine. Aiden ran ahead, magnifying glass swinging from his wrist like a badge. He crouched near a maple and popped back up with treasure. “Mom, I found a pretty stone!”

Mary admired the stone like it had applied for the role of leadership. She kept half her attention on the grown-ups—on Robert’s cheerfulness, Helen’s softened urgency, Linda’s phone which had made brief appearances and now hid like a co-conspirator.

“You keep checking that,” Mary said to Linda casually, the way you ask a stranger on a plane where they’re going even though you both know it’s the same place.

“Huh?” Linda looked up too fast. “No, it’s just… the time.” Her voice tripped on the word time like she’d never said it before.

Mary smiled and said nothing. She took inventory instead: her parents’ light bags, Linda’s performance wear, the way Robert’s shoulders had tightened into straight lines. She did not write any of this down. She felt it.

The path narrowed to a single track stitched into the slope. It wasn’t hard hiking, but it wasn’t indolent either. The trees stood close enough together to be a congregation or a barricade, depending on your mood. Aiden went first, then Robert, then Mary with her mother, and Linda last like punctuation. As they climbed, the forest worked its old therapy—the hush, the small birds gossiping, the way the earth forgave missteps with soft ground.

Mary almost convinced herself she’d been unreasonable, that tiredness had dressed up as paranoia, when the trail turned and spit them out onto a rocky shelf. The vista knocked the breath out of the day. The valley fell away fast and forever, a green bowl with a blue drop at the bottom. Wind muscled the edges. Mary’s stomach sloshed; she had always preferred her gravity intimate.

“It’s beautiful,” Aiden said, and when children say it, beauty gets a raise.

“Look, buddy,” Robert said, placing a hand on Aiden’s small shoulder, sliding him a step toward the edge. “See the lake? That tiny sparkle?”

“Dad,” Mary said, the word colder than she meant, “back.”

“It’s all right,” Robert said, and his voice did something Mary’s training pricked at: he performed calm. Calm isn’t a costume you should ever have to put on in front of your daughter on a cliff. “I just want to show him.”

Mary took three steps and wrapped her hand around Aiden’s wrist with a grip that would embarrass decorum. “Come here,” she said. Aiden moved, obedient and startled.

Something tugged at Mary’s arm. Linda’s fingers dug in with unearned intimacy. Mary turned, and the face that had belonged to Mary’s sister for thirty-one years had a stranger’s light behind the eyes.

“Mary,” Linda said, falsely cordial, “there’s something I want to show you.”

“Let Aiden stand with me first,” Mary said, because motherhood is a reflex not a plan.

“No,” Linda said. “Aiden should see it, too.” Her mouth did a thing that wasn’t a smile.

Mary tried to pull free. Hands closed the space behind her. Helen’s breath near her ear, Robert shifting. The choreography was too smooth to be spontaneous.

“Honey,” Helen said, and the endearment felt like it had spikes. “You were always a good child.”

That sentence should have been a quilt. It felt like a scalpel.

“Sometimes,” Helen continued, voice soft and terrible, “sacrifices are necessary. For the family.”

She pushed.

The world tilted toward the wrong. Mary pinwheeled, catching herself on the traction of a small lip of rock, and in the strobe of panic she saw it: Robert lifting Aiden—Aiden startled enough to shout “Grandpa!”—and the body-language vector of a throw.

“Let go of my son!” Mary screamed, and the wind tore her voice and flung it back at her.

The next seconds accordion. Mary lunged, catching Aiden’s jacket with a hand that could hold an artery closed and a boy closer. Linda shoved with both hands, the way you might heave a box toward a donation truck in a life you weren’t trying to end.

Then they were falling.

Mary had time to think of geometry. She had time to think of God, and work schedules, and the fact that she hadn’t rotated her ankle in years, and how stupid it would be to die because someone you love creates a laboratory where cruelty is the experiment and you are the rat. Mostly, she had time to think one thought: Aiden.

She wrapped herself around him as the cliff face threw branches and stones and insults. The human body is not meant to bounce. It does anyway. Pain lit up in her like lights on a runway. Her right leg screamed, her left arm became theory, her ribs knelt. They hit the bottom with a finality that suggested a comment section and then the worst quiet in the world: the kind after.

Her eyes opened because sometimes eyes do you the favor of doing it for you. Aiden lay stocked against her, small voice a thread. “Mom?”

“I’m here,” she said, and the words were a measurement and a prayer. She tried to move her left arm and found it unwilling. Her right leg had decided to stop participating in the day. She did a quick inventory—the nurse in her shoving the mother aside just long enough to acquire data. Aiden had bruises, scratches, shock. His pupils were reactive, his breath a quick seesaw, his trust unreasonable and full.

Voices drifted from above, threads pulled tight and then tugged by wind.

“Can you see?” Helen, her mother, sounding like someone checking on a casserole.

“Are they moving?” Robert, her father, sounding like a man discussing weather.

“Too dangerous to go down,” Linda, her sister, the syllables sloppy with adrenaline. “They’re not moving. Let’s go. No one comes here.”

Mary’s pulse steadied long enough to be a decision. She held Aiden as if he were evidence and consequence and everything else. Her heart performed an arithmetic no textbook covers: she could be afraid and she could be calm and she could be a mother and she could be a field medic and she could be the person whose life did not end on a Saturday because three people she used to love decided a cliff could do paperwork.

Then Linda’s voice, bright with relief and venom in equal parts: “Don’t regret it. Now Thomas and I are free. We’ll get the insurance money. The obstacles are gone. We never needed that child in the first place.”

It is one thing to suspect. It is another to have the sentence stitched onto your skin.

Mary felt the ground steady with the nauseating click of puzzles solved. The six months of late returns. The looks that lasted too long. The silence that tasted metallic. Thomas had not just been busy. He had been building a life where she did not exist. And Linda—her sister, catalog queen, sarcasm with great hair—had poked a hole in their family and decided to climb through.

Mary’s parents had helped. For money. She had been a nurse long enough to know how many reasons people find for the unspeakable: fear, love, habit, debt. None of them stands up to daylight. All of them demand rent.

The voices receded, steps crunching gravel, then silence returned like a coward.

Aiden’s mouth pressed close to her ear. “Mom,” he whispered, small as a continent, “we shouldn’t move yet.”

Mary closed her eyes and understood the miracle of her son twice over. He had seen. He had heard. He had chosen. She let every muscle go slack. The minutes elongated into something awful. When enough time passed that even the squirrels had relaxed, Mary breathed again.

The phone in her pocket was a glitter of shards. She had reception for despair and nothing else. The sun considered leaving. The forest reset its soundtrack. Aiden’s hand slid into hers with absurd politeness; he was, after all, six.

“Can you walk?” Mary asked him, gentle as if asking a bird to evaluate flight. The pain behind her eyes marched in circles; her body had become a litany.

“Yes,” he said, voice too brave to be a lie. “I’ll go get help.”

“No,” she said instantly, and did not add I don’t let you out of my sight anymore, not for anything the world can make. “We go together.”

They started. Together meant Mary using a branch for a crutch and Aiden scanning the ground for friendlier angles as if he’d been trained by parks rangers and loss. Together meant stopping every dozen steps for breath that hitched. Together meant Aiden saying, “It’s flatter over here,” with a confidence that floated both of them. Together meant Mary telling her own body that this was the only plan and it could file its complaints later.

By moonrise, the trees looked like steeples. Mary’s watch glowed 11:03. Aiden leaned against her, pretending not to be tired. They sat under a beech tree that looked like it had seen things. The forest pressed in with a kindness it couldn’t possibly mean.

“Mom,” Aiden said, voice made of socks and a question, “will Dad not come back anymore?”

Mary’s mouth filled with everything at once. The truth. The urge to lie. The wish that there were version of the story that didn’t break his heart twice. “Dad…” she began, and picked her way across the sentence like a woman choosing stones in a river. “Dad won’t be able to live with us anymore. But it’s okay. I will always protect you.”

He nodded and tucked himself into a place on her side that had been engineered for exactly that. “Grandpa and Grandma?” he asked, small morphology for big betrayals.

“Them too,” Mary said, and her voice did not shake because there were wolves in this forest—metaphorical ones; the real ones had fled Ohio a hundred years ago—and she would not call them with tremors.

“Aunt Linda said she and Dad would go somewhere together,” Aiden said, offering the fact like a breadcrumb.

“I heard,” Mary said, holding back the kind of tears you never forgive yourself for crying in front of your child. “But it’s okay. We’re alive, and we’re together, and we are not who they think we are.”

They walked again. The forest surrendered a path like a riddle that had decided to be easy. Dawn found them where the main trail widened and people who like titanium walking poles appear in packs of two. A middle-aged couple rounded the bend and stopped dead.

“Oh my god,” the man said, moving toward them with hands extended and a heart on his face. “Are you all right?”

Mary’s laugh came out as a cough. “We fell from a cliff,” she said, and the ridiculousness of it made her want to sit down and apply for a new genre.

The woman called 911 with a voice that had practice. They wrapped Mary and Aiden in emergency blankets that sounded like applause. Someone found an orange and offered it to Aiden like a sacrament. He ate with the ferocity of someone who had been brave and hadn’t realized it required calories.

At the hospital, the lights were the familiar wrong color and the right ones. Mary answered triage questions with her nurse brain and her mother heart and her broken body. The doctor said things like multiples and fractures and internal and we’ve got you, which is all you ever want to hear from medicine or a person. Aiden’s bruises were impressive; his resilience was obscene. “Your mom cushioned you,” the doctor told him, the complement wrapped in science. “She’s a brave mother.”

Detective Brown appeared after radiology, the kind of cop who’d been hired for both his pen and his face. He asked to talk and waited for the yes like it mattered. Mary said it did. She told the story with just enough -ly words to locate the actions. She told him about the cliff and the push and the voices that sounded like her childhood and a contract being shredded. She told him about Linda’s sentence—“Now Thomas and I are free. We’ll get the insurance money. We never needed that child”—and watched the detective write it down with the care of an archivist.

“We’ve tried reaching Thomas,” he said. “He hasn’t arrived. We’ll keep trying.”

“He won’t,” Mary said, and if bitterness were sugar her voice would have rotted teeth. “He’s part of it. He and Linda. My parents, too. They promised them money.” Saying it out loud turned theory into document.

A child psychologist knelt beside Aiden with crayons and the kind of patience you bottle and sell to make a million dollars and a better world. Aiden explained things in six-year-old, which turned out to be a dialect of truth. His details matched Mary’s. The detective’s pen did its work. The machine started.

By evening, Brown had warrants and questions and a simmer. By morning, patrol cars had rolled toward four locations, and the town whose crime blotter usually featured “complaint about loud rooster” had something it wasn’t built for and handled anyway.

Mary slept in slices. When she woke, she dreamed of the edge and then of the bottom and then of her son’s hand finding her ear with an instruction that had saved them. She dreamed of her mother saying you were always a good child and she woke with her face wet and the wild thought: I still am.

Two days later, Detective Brown returned with a face that had seen a version of justice. Thomas had been arrested in a parking lot thirty miles away, getting into Linda’s car with a go-bag that looked like Amazon had made a list. Linda had been arrested with him, tears for the camera and a mouth that did not know silence. Robert and Helen, at their kitchen table, had tried to pretend morning coffee could solve anything. The warrants turned their house inside out with paperwork.

Brown explained the insurance—the one Mary hadn’t remembered signing, the beneficiary arrangements that had turned her life into a ledger. He explained the statements and the interviews and how quickly even a small town can learn to say attempted murder without choking on it. He explained arraignment and bail and the way the system dresses itself for these occasions.

Mary listened, hand in Aiden’s, body strapped together like hope. She nodded when she had to and stared out of the window when she could. In the glass, she saw a woman who had fallen off a cliff and found a staircase on the way down.

When Brown left, Mary asked for a pen. She pulled the tray closer and wrote a sentence on the paper place mat nurses put under soda cans: We survived. On purpose. She slid it under the plastic edge of her bedside tray like a secret.

Aiden slept with a stuffed dog the volunteer brought him and the world tucked itself into Second Chances. Outside, Willowbrook kept changing quietly, the way it knew how. The maples got on with their gossip. The hospital lights hummed. Mary closed her eyes and, for the first time in days, let her body do the simple thing: exist.

Part Two: Paper Trails

Hospitals are built for two kinds of truths: the measurable kind, and the kind that arrives in tremors. The first came in numbers—BP, SpO₂, hematocrit, fracture lines labeled with tidy arrows on a scan. The second came in visits and voices and the way the night shift placed a hand on Mary’s shoulder before they left the room, a small ritual that said stay.

By Sunday, Mary knew the rhythm of beeps in Room 412. Aiden napped in lopsided intervals, growing ferociously, it seemed, every time he closed his eyes. He kept his stuffed dog tucked under his chin and a crayon in his fist like he’d negotiated both as non-negotiables. When he woke, he drew pictures: a tree with a cape, a cliff that looked suspiciously like a villain with bad hair, a tiny boy holding the hand of a woman whose stick-figure shoulders were broad enough to hold up the sky.

Detective Brown came back mid-morning with a legal pad and coffee that looked like it had survived a war. “How’s the pain?” he asked, which told Mary he’d been raised right.

“Chattier than usual,” she said.

He smiled, then turned the page. “We picked up Thomas and Linda,” he said, voice even. “Your parents, too. They didn’t make us chase them far.”

“Thomas had a bag,” Mary said. “Let me guess.”

“Passport, cash, clothes,” Brown confirmed. “A book about national parks, which I am choosing to read as irony.”

Mary breathed out through her nose. “He never liked camping,” she said, and the joke arrived brittle and right.

“We executed warrants at your parents’ house,” Brown continued. “We found notes—‘hike, Saturday,’ ‘no cell service,’ ‘bring rope’ crossed out, which is not how you want to read that word at breakfast. We found a printout of your life insurance policy. We’ve asked the insurer for application files. The agent remembers Thomas ‘taking the lead.’”

“He always liked a lead,” Mary said, and was surprised to hear the acid has a backbeat.

“We’re going to arraignment tomorrow,” Brown said. “I’ll keep you updated on bail conditions. Also—this may feel sideways—but our victim advocate can help with a civil protective order, school notifications, paperwork. There’s paperwork for everything, even this.”

In another life, Mary had loved paperwork. It made hospital machinery go; it made the world accountable to itself. Now the thought that forms could hold anything this heavy made her want to cry and file it.

“Detective,” she said. “Thank you.”

Brown’s mouth ticked into something that wasn’t quite a smile and wasn’t quite a promise. “We’ll see it through,” he said, and left behind a card, a checklist, and the sense that a stranger had joined the army on her side.

The arraignment was the following morning in a courtroom where the fluorescent lights tried to be indifferent. Mary watched on a live stream from her hospital bed because the prosecutor didn’t want the defendants to see her yet. It felt both cowardly and wise, which is how healing sometimes feels when you’re doing it correctly.

The camera panned a room that pretended to be boring on purpose. The judge—Hartman, square shoulders, clipped consonants—sat like an exclamation point. Assistant Prosecutor Vega, young and precise, recited charges with the care of a person shaved by details: attempted murder, aggravated assault, conspiracy, child endangerment, insurance fraud, tampering. Words Mary had only ever seen on forms put on coats and walked around.

Thomas wore a county-issue orange that did his complexion no favors and his soul fewer. Linda stood beside him, blazer wrinkled, mascara honest. Robert and Helen, in separate frames, looked like a cautionary tale about inheritance. Thomas’s lawyer threaded sentences together about misunderstanding and panic and an “unfortunate accident during a family outing.” Linda’s attorney coughed up tears and used the words under the influence of another.

Vega asked for high bail with GPS, no contact, surrender of passports, and daily check-ins, her tone steady as a nurse pushing a med. Judge Hartman set numbers that sounded like mortgage payments in the wrong life. “If you breathe within a hundred yards of Ms. Wilson or her son,” he said, “I will revoke bail before your feet hit the sidewalk.” The gavel didn’t bang; it didn’t need to.

Mary closed the laptop and stared at the rectangle imprint on her desk tray. Aiden looked up from a coloring book and asked, “Is the judge nice?” Mary kissed his hair. “He knows how to keep people safe,” she said, which is close enough to a definition to use for now.

When the day nurse changed the bag on Mary’s IV, she smiled the crisp smile of someone who has hidden a bakery in her locker. “I brought you contraband,” she whispered, and revealed not sugar but information: Jennifer from Med-Surg had asked if she could stop by. Mary knew Jennifer the way nurses know each other—chit-chat at the coffee pot, med-passes traded when the shift goes south, the quiet alliances of people who refuse to let a system eat the people in it.

Jennifer knocked and entered already apologizing. “I brought lip balm,” she said. “Hospital air is a gossip.”

Mary laughed. “You didn’t have to.”

“I can’t fix bones,” Jennifer said, perching on the visitor’s chair, “but I can throw ChapStick at problems.” She glanced at Aiden, who was building a hospital out of graham crackers. “How’s our bravest scientist?”

Aiden gave her a solemn nod that said, as you were.

When he bent back to his work, Jennifer lowered her voice. “I’m a survivor,” she said, the word out of her mouth like a badge and a bruise. “Different story, same map. If you want a therapist recommendation who won’t turn your pain into a TED Talk, I have names. If you want a lawyer who thinks paperwork is art, I have numbers. If you want a casserole that can lift a Toyota, my sister makes one.”

Mary swallowed the cry that came up like salt water. “All of the above,” she said. “But not tonight.”

“Good,” Jennifer said. “Tonight you get lip balm and the promise that your life will feel like yours again.” She stood, squeezed Mary’s foot where the blanket made a hill, and added, “I’m on nights this week, so text at 3 a.m. if the ceiling gets loud.”

After she left, Mary put the lip balm in the drawer where the hospital keeps the extra socks and the optimism. She took it out again and applied it. It felt small and exactly adequate.

News seeped like water under a door. In a town that measured gossip by church potlucks, people learned fast they could weaponize a whisper if they weren’t careful. The hospital kept Mary’s door closed and her chart labeled no information to callers. Her friend Carly from Admissions posted a sign-up sheet for meals and rides with the efficiency of a general. The door to the Wilson apartment was covered in polite Post-its and the savage kindness of casseroles.

For every “I never liked Linda anyway,” there was a “Let us know if you need to borrow a lawnmower.” For every specious theory about Thomas’s debt and masculinity, there was a bag of groceries, a stack of coloring books, and a gift card to a pizza place that had solved more problems than the town council. Mary learned to receive without apologizing. She practiced a new sentence: “Thank you.”

Brown filed indictments. Vega filed motions. A kind-faced woman from the victim advocate unit named Tamika sat at Mary’s bedside and explained the ironclad pleasures of restraining orders. “We’ll put your names in big red letters on the school and at the clinic,” she said. “We’ll give the principal and nurse a copy of the orders. We’ll make a plan for pick-up and drop-off. The law is not a blanket,” she added, “but it can be a jacket.”

When Aiden slept, Mary filled out forms in the careful block letters of a nurse who knows paperwork sometimes keeps people alive. She checked boxes that told the truth. She initialed lines that underlined reality. She did not find catharsis there. She found scaffolding, which is the next best thing.

Healing went the way healing always does: annoyingly slow in the moments and alarmingly fast in the rearview. Mary traded the hospital for home with a pharmacy bag, a PT schedule, and a hug from the discharge planner that could have fixed potholes. She learned to navigate crutches while Aiden turned into a sherpa with dimples. He invented games that honored her restrictions and trashed gravity. He’s six, she thought, and also seventy. Children contain multitudes because they haven’t learned the inverse yet.

Willowbrook’s temperature dropped into the part of October where the sky pretends not to be interested in sunlight. Mary moved from couch to chair to bed in tidy circuits. Jennifer stopped by after nights with coffee and stories. “There’s a woman on 5 who names her IV poles,” she said one morning. “I told her to start a band.” They laughed and then did not. Sometimes, laughter is the first language trauma learns again.

When the DA’s office asked for a formal statement, Mary prepared like she was scrubbing in. Jessica—no, that belonged to another story; Vega’s paralegal, a solemn third-year named Victor—helped Mary rehearse without turning it into theater. Aiden met with Child Services in a room that had made the poor aesthetic choice to paint itself mint green. He narrated with the accuracy of a court reporter and the slang of kindergarten. He used his hands to show height (the cliff), length (the trail), and width (his mother’s arms). The caseworkers wrote “resilient” and “clear” and then went out to their cars and cried where no one could see.

Brown’s investigation gathered shapely nouns: phone records, text messages, a series of withdrawals, a loan against a truck Thomas had already killed once and resurrected with jumper cables and entitlement. There were notes on Linda’s phone, drafts that made the hair stand up on the back of Mary’s neck: Saturday — new trail — no one around — what to say if EMTs ask (accident. she slipped.) There were searches: life insurance payout accident? and how far to fall and live. The internet had done what it always does—provide rope.

Mary read the discovery packet with a gaze that flamed and frosted. “They chose it,” she said to her ceiling at three in the morning, where grief often holds office hours. “They sat at tables and picked a plan.”

Aiden started drawing mountains with stairs.

The preliminary hearing was an exercise in language that sounded like careful violence. Mary rolled into court in a borrowed wheelchair because the walk from the parking lot to the past is absurdly far. Brown nodded from the back row. Tamika sat at the aisle like a polite bouncer. The prosecutor’s table hosted highlighters and inevitability. The defense table looked like it had survived a hurricane and called it weather.

Mary testified without drafting a novel out of her pain. She said “my mother pushed me” in a tone that made a court reporter swallow hard and keep typing. She said “my father lifted my son” without flinching at father because some words deserve a hard exit. She said “my sister said—” and Vega asked the court to accept a transcript of those words instead of a dramatization, and Judge Hartman assented, which is sometimes how mercy dresses itself in a courtroom.

Aiden testified with a stuffed dog on his lap and the kind of courage that made the bailiff look away. “Grandpa put his hands on me,” he said, and “Mom saved me,” and “We fell,” and “We got up.”

The defense tried to redirect what happened into accident by way of tragedy. Vega stopped them at grammar. “The cliff did not push itself,” she said. Later, in the hallway, she touched Mary’s elbow like a benediction. “You did well,” she said.

Mary went home and slept for four hours in the middle of the day like her body had filed a request and finally found the manager.

December unrolled its cold like a carpet. The DA offered a deal: plead to top counts, forfeiture of policy payouts, no-contact orders, Erica Hartman’s sentencing discretion. Thomas balked until Linda’s lawyer leaned into his ear and spoke a word every conspirator eventually learns: evidence. He pled. Linda pled. Robert and Helen broke their pleas into pieces and then swallowed them.

On the day the court accepted, Mary felt less like celebrating and more like someone had moved a weight from one shelf to another. Christmas came with paper crowns from the crackers and a small tree Aiden declared “the bravest.” Under it, he put three handmade ornaments shaped like shields with the letters M & A & Us. Mary hung them in the front and fell asleep on the couch with the lights still on and the quiet of the house finally not a threat.

In January—because hope runs on a calendar whether you want it to or not—Mary went to her first physical therapy session, and a woman named Carmen bent her right leg in a way that felt like a lesson and a dare. “Hurt is not harm,” Carmen said. “We’re teaching parts of you to trust again.” Mary bit her cheek and learned to push back at stiffness, which is a metaphor you can use anywhere.

Aiden started sleeping with the hall light on. When he woke, it was with a small cry that sounded like a match struck in a cavern. Mary padded in and sat on the floor beside his bed, hand on his back, telling him the story of the day—the safe parts, the silly parts—to crowd out the unwelcome director’s cut of memory. “Tell me about the tree with the cape,” he would whisper, and she would. The tree always won.

One Sunday, on the way back from the grocery store—apples, milk, detergent, and the criterion by which civilization should be judged: enough toilet paper—Mary saw a flyer pinned to the library corkboard: Community Grief Group: For Survivors and Those Who Love Them. Wednesdays, 7 p.m. She took a photo of it and then, because she had decided this year belonged to uncomfortable bravery, she went.

The room smelled like church basement and hope. People sat in a circle like a cliché because sometimes clichés are how you hold each other up. Jennifer sat at Mary’s right. A woman with a throat tattoo sat at her left. The facilitator, a man with the calm of a retired weather anchor, said, “We’re here because our stories refused to be quiet.” Mary exhaled. She spoke when it was her turn. She did not make her story smaller to make the room more comfortable. No one left. The circle held.

Sentencing approached the way storms do—announced, rescheduled by systems beyond anyone in the room, then immediate. On the morning itself, Mary braided her hair back with hands that didn’t shake and put on the good sweater—the one Linda had once teased as too earnest—and thought, Not everything needs a joke to survive it. Aiden wore the shirt with the tiny anchors; he said it made him feel like a captain.

Vega read into the record words that sounded like nails in the right wood. Judge Hartman accepted pleas and then did a thing Mary hadn’t expected: he spoke as if the room contained citizens, not just parts. “The law can punish,” he said. “It can’t mend. That’s your work. It looks like you’re doing it.”

He sentenced Thomas and Linda each to twenty-five years with review in fifteen. He sentenced Robert and Helen to fifteen with parole conditions Mary couldn’t list later because all she heard was the sound of a door somewhere closing with a dignity that did not exist on the day of the cliff.

Outside, the air bit. Reporters trailed with microphones and the hunger of puppies. Mary said no to all of them. Tamika ran interference with the elegance of a woman who could organize a parade in a snowstorm.

At home, Mary took the House of Ordinary back by making grilled cheese and reading Charlotte’s Web out loud until Aiden fell asleep mid-some pig. She washed the dishes slowly, letting the warm water scold her hands. The quiet felt earned.

She took her phone and typed a message to Jennifer: We did it. Jennifer replied with a string of hearts that looked like a parade of survivors.

Mary sat on the couch with her leg propped up, stared at the ceiling, and thought of Colorado, of mountains that looked like the edge of the world in a way that didn’t threaten and did promise. Jennifer’s sister, Martha, had a spare annex in a guesthouse where the nights came dark and honest. There was a clinic in town that needed a nurse who could make paperwork behave and hold a hand without flinching. There was a school where the principal believed in recess like a human right.

“Mom,” Aiden murmured from the doorway, hair in astrophysics. “Are we going to move to the big mountains?”

“Maybe,” Mary said. “Do you want to?”

“Yes,” he said, with the confidence of a person who’d made friends with altitude already in his mind. “I want to teach the mountains to wear capes.”

“Then we should go help them,” Mary said.

He padded over and climbed onto the couch beside her, careful of her leg, careful in all the ways he had learned to be and still, somehow, six. They looked out the window at willow branches drawing winter across the sky like a note.

“We’re okay,” Aiden said, a statement and a command.

“We are,” Mary said. And it was true enough to build on.

Two weeks later, paperwork turned into tickets, turned into boxes, turned into goodbyes at a diner that had seen too much coffee and not enough justice. Friends came with hugs that bruised in the right way. Carly from Admissions cried into her menu and said she would mail them a picture of the front desk every month so they wouldn’t forget what fluorescent lighting looks like. Brown swung by with a snow globe from the courthouse gift shop—an inexplicable thing that made sense in Willowbrook. “It’s good to have one world you can shake and control,” he said. “Just one.”

Mary hugged him like she’d known him since the bus route years. “You gave us our story back,” she said.

“I took notes,” Brown said. “You did the rest.”

On the last night in their apartment, Mary walked from room to room, touching doors, murmuring thanks the way her grandmother had taught her to when leaving a familiar place. She stopped at the refrigerator, unpinned the first drawing where a dog, a cat, and three stick figures held hands, and replaced it with a new one. Aiden had drawn a mountain with—of course—a cape. At the base, two small figures held hands. Above them, in his unmistakable block letters, he’d written, US.

Mary laughed, warmed dinner in a pan, and felt the exact sensation of a life turning its own page.

In the morning, they loaded the car. Willowbrook let them go without drama; the town had not made a habit of chasing stories beyond its borders. As they pulled onto the highway, Aiden pressed his face to the window and said, “Bye, trees,” and then, softer, “Bye, cliff,” because naming things is a way of not letting them name you.

Mary drove with both hands on the wheel and the future in the passenger seat. The road unspooled west, and with it, the particular quiet of Ohio gave way to something else—thinner air, louder sky, a horizon that didn’t pretend to be tame.

They didn’t look back. Not because they weren’t grateful, but because forward had finally started speaking loud enough to hear.

Part Three: Colorado Air

Colorado had the audacity to be beautiful even when you were broken. Mary noticed it first from the airplane window—the mountains like folded paper, the valleys inked with green, the sky bragging in a blue Boston or Ohio would have apologized for. When the wheels touched down in Denver, Aiden clapped so loudly the row behind them joined in.

Martha, Jennifer’s sister, was waiting in Arrivals with a cardboard sign that said MARY + AIDEN = NEW START. She was the kind of woman who had perfected both the one-armed hug and the casserole handshake. “Welcome home,” she said, even though technically it wasn’t yet.

The guesthouse Martha ran smelled like woodsmoke and cinnamon, two aromas that know how to earn trust quickly. Mary and Aiden’s room was small but bright, with a quilt Martha claimed had “mended itself” over the years. Out the window was a ridgeline that looked like it had been painted while someone was laughing.

“This is ours?” Aiden asked, spinning once like he was testing the acoustics.

“For now,” Mary said. “Until we find what’s next.”

He grinned. “What’s next is pancakes.” Martha, overhearing, declared him the most sensible man she’d met all week and fired up the griddle.

The local clinic wasn’t much to look at—two exam rooms, a waiting area with six mismatched chairs, a poster about flu shots that could have retired—but it needed a nurse, and Mary needed to be useful. Dr. Han, a soft-spoken internist who wore bow ties without irony, interviewed her with a checklist.

“You’ve seen trauma?” he asked.

Mary almost laughed. “Yes. Both on and off duty.”

“You can handle paperwork?”

She smiled. “I make paperwork behave.”

“You can tell a patient the truth without cruelty?”

She paused, then said, “It’s the only way I know.”

He nodded. “Welcome aboard.”

By the end of her first week, she’d restarted their filing system, fixed the blood pressure cuff that everyone swore was “just moody,” and convinced the front desk to stop storing Band-Aids with tongue depressors. It was a small victory, but small victories were the scaffolding of survival.

Aiden started second grade at Willow Creek Elementary, where the hallways smelled like crayons and ambition. On the first day, Mary walked him in. The principal, David Clark, greeted them with a handshake and the kind of smile that made you want to listen to him read weather reports.

“Your son’s new teacher is Ms. Patel,” David said. “She believes in recess as a human right.”

“That’s good,” Mary said. “So does he.”

Aiden’s classroom had a guinea pig named Biscuit and a wall covered in paper stars. By the time Mary came back that afternoon, Aiden was playing tag with two boys named Jason and Mike and looked like he’d been doing it for years.

“Mom,” he said breathlessly, “we’re making a club. The Rule is: no cliffs.”

Mary laughed, a sound she hadn’t heard in her own throat in too long.

At night, in the guesthouse kitchen, Martha poured tea and asked gentle questions. “Are you sleeping?”

“Badly,” Mary admitted.

“Nightmares?”

“Every night. But less sharp than before.”

Martha nodded. “Healing is boring like that—incremental. Like watching paint dry, if paint occasionally screamed.”

Jennifer called from Ohio to check in, voice full of that night-shift steadiness. “Don’t be brave for the sake of being brave,” she said. “Be brave because you’ve got something you’re building. That’s the only kind that sticks.”

Mary listened and thought of the list taped inside her old mug cabinet. She decided she’d make a new one here.

House Policy (Colorado Edition):

Pancakes are medicinal.

Therapy counts as homework.

Family = love that keeps you safe.

Mountains wear capes.

She pinned it to the fridge with a magnet shaped like a trout.

David Clark began showing up at the clinic under the guise of “checking on students’ files.” Sometimes he brought biscotti from the bakery near the school. Sometimes he stayed to help Martha carry boxes of supplies in. Always, he asked about Aiden as if the boy’s progress mattered more than his own reputation.

One evening, after clinic hours, Mary found him outside leaning on the porch railing, watching the mountains tint purple.

“Your son is remarkable,” he said. “He carries himself like someone twice his age.”

“He’s had to,” Mary said.

David looked at her, then looked away, respectful. “And you?”

“I’m learning how to breathe here.”

“Good place for it,” he said. “Air’s thin, but honest.”

Mary smiled, small and reluctant. She was not ready for more. But she was grateful to be asked.

Spring found them before they expected it. Snow melted into a creek behind the guesthouse. Aiden learned to ride a borrowed bike, wobbling at first, then steady, then flying down the dirt road like gravity had agreed to step aside.

“Mom, look!” he shouted, arms wide for one insane second before grabbing the handlebars again. “I’m free!”

Mary clapped, heart seizing and swelling all at once. She thought: That’s the word. Free.

And for the first time since the cliff, it didn’t feel like a lie.

Part Four: The Trial and the Echoes

The summons came in March, slipped into a manila envelope that smelled faintly of government and regret. Mary sat at the guesthouse kitchen table, Aiden coloring a dragon beside her, when she opened it.

“Court date,” she said aloud, and her voice came out steadier than she felt.

Martha leaned over her shoulder. “Back in Ohio?”

Mary nodded. “They want me there. Testimony.”

Aiden looked up, green crayon poised like a question mark. “Do we have to go back to the bad place?”

Mary stroked his hair. “Just for a little while. To tell the truth. Then we come back here.”

The courthouse in Columbus was larger and colder than the one in Willowbrook, all glass and metal detectors and echoes that didn’t care about your nerves. Mary wheeled herself in—her leg still stiff, her arm mended but weak—and tried not to look at the benches where once she would have sat with her parents, or her husband, or her sister.

The defendants sat in a row, oranges and grays, heads bowed in something that wasn’t shame. Thomas’s jaw was clenched, Linda stared at the table, Robert and Helen looked like retirees waiting for a bus. Mary wondered if they remembered the picnic blanket days, the storybooks, the times when she thought family meant safety.

Assistant Prosecutor Vega called her to the stand. Mary swore the oath, hand steady.

“Mrs. Wilson,” Vega began, “can you tell the court what happened on the day of the hike?”

Mary took a breath. “We drove up the mountain road. They said it was a hidden place. At the cliff, my mother pushed me. My father lifted my son. My sister said, ‘Now Thomas and I are free.’ They wanted the insurance money.”

The courtroom went silent, except for the scratch of the court reporter’s keys.

Vega asked about her injuries. Mary answered clinically: “Right femur fracture. Left ulna fracture. Multiple contusions. Internal bleeding. Treated, stabilized.” She didn’t let her voice tremble.

“Why did you survive?” Vega asked.

Mary looked at the jury. “Because my son told me to play dead. Because I held him. Because we refused to give up.”

She sat down, and the silence that followed was heavier than any gavel.

Then it was Aiden’s turn. He wore his best shirt with the tiny anchors and clutched Biscuit the guinea pig plush Ms. Patel had given him for luck.

“Do you know the difference between telling the truth and telling a lie?” Vega asked.

“Yes,” Aiden said firmly. “A lie is when you say Dad loves you.” The gallery gasped, a sound that cut.

“Can you tell us what happened on the mountain?”

“Grandpa put his hands on me. Grandma said sacrifices. Aunt Linda said she didn’t need me. Mom saved me. We fell. We got up.”

It was enough.

The defense tried, of course. They said Robert and Helen were too frail to mean harm. They said Linda was manipulated. They said Thomas panicked under debt. They said words like accident and misunderstanding until the jury’s eyes glazed over.

Vega closed with fire. “This was not a stumble on a trail. This was a family deciding who was worth more dead than alive. And the only reason we know the truth is because Mary and Aiden lived to tell it.”

The jury needed three hours.

Verdict: guilty on all counts. Attempted murder. Conspiracy. Insurance fraud.

Sentences: Thomas and Linda, twenty-five years each, parole possible after fifteen. Robert and Helen, fifteen years each. The courtroom exhaled.

But the drama wasn’t quite done. As bailiffs moved to escort them out, Thomas snapped, “This is your fault, Mary. You ruined everything.”

Linda shouted too, mascara streaking. “I’m better for him than you ever were! That boy is weak, just like you!”

The judge’s gavel finally came down, sharp. “Silence. Remove them.”

Mary sat, eyes closed. She felt nothing for Thomas’s fury, nothing for Linda’s venom, nothing for her parents’ bowed heads. She had said goodbye already.

Back in Colorado, the air greeted her like an ally. Aiden ran to Jason and Mike at school, showing off the dragon he’d finished coloring during the trial. “It’s got armor,” he explained. “Like me.”

Mary unpacked their suitcases in the guesthouse and folded away the court clothes. She hung the House Policy list on the fridge again, this time in neat print, with one new line at the bottom.

5. Truth is heavy, but we can carry it.

She stood back, reading it. Aiden padded in, mouth full of pancake. “Mom, can we add one more?”

“What’s that?”

He thought. “Rule six: No cliffs.”

Mary laughed, hugged him, and wrote it down.

That night, as the mountains turned purple under the setting sun, Mary sat on the porch with a mug of tea. David Clark stopped by, dropping off a stack of books for Aiden. “He’s thriving,” he said. “Resilient. He’ll be all right.”

“So will I,” Mary said, surprising herself with the certainty.

David smiled. “I don’t doubt it.”

Mary looked at the sky, then at her son’s laughter spilling from inside. The echoes of betrayal were still there, but they were drowned now by something louder: survival, and the possibility of joy.

The cliff had tried to end them. Instead, it had taught them how to climb.

Part Five: New Bonds

Colorado had a way of sneaking into you. The mountains weren’t just scenery; they were witnesses, standing there with arms crossed, waiting to see if you would live up to their scale. Mary found herself breathing deeper, even when her bones ached, even when nightmares tugged at her sleep. She had survived Ohio. Now she wanted to belong here.

Settling Roots

By summer, the guesthouse felt less like a stopover and more like a cocoon. Martha refused rent some months—“You pay me in good company,” she insisted—and made Aiden pancakes every Sunday with blueberries arranged into smiley faces.

At the clinic, Mary’s shifts lengthened. Patients brought her jars of jam or zucchini the size of baseball bats. Dr. Han teased her about being “the most popular new nurse in three counties.” She answered with a smile she hadn’t known she still had.

Aiden thrived. He came home dusty, his hair sun-bleached, with stories about forts built in the woods behind school. His teachers marveled at his kindness. “He’s the first to notice when someone’s left out,” Ms. Patel told Mary. “He tells them, ‘Come on, we’re a team.’”

Mary wanted to weep at that. Her boy, who had seen betrayal so raw, was teaching others about belonging.

The Principal

David Clark visited often under the pretense of paperwork or Biscuit the guinea pig’s latest antics. He had a way of standing on the porch with his hands in his pockets, looking like he wasn’t sure if he was welcome, which only made him more so.

One evening, after dropping off Aiden’s report card, he lingered as the sky bled orange. “I don’t mean to intrude,” he said, “but… you’ve done something remarkable here.”

“I’m just keeping us alive,” Mary said.

He shook his head. “No. You’ve shown Aiden that love is stronger than blood. That’s… rare.”

Mary looked at him, then back at the mountains. “Rare doesn’t mean impossible.”

They didn’t call it anything yet. But something was growing, patient as the tree outside the porch that leaned toward the sun.

The Past Still Echoes

News from Ohio came in trickles. Letters from the victim advocate unit confirmed the sentences. Reports said Thomas and Linda’s relationship soured quickly behind bars, each blaming the other. Robert and Helen were said to spend their days justifying, not repenting. Mary read the updates once, then folded them away in a drawer she didn’t open again.

One night, she dreamed of the cliff. But this time, she and Aiden didn’t fall. They grew wings. She woke with tears drying on her face and Aiden snoring gently at her side.

She whispered into the dark, “We’re free.”

A Birthday

On Aiden’s eighth birthday, the guesthouse yard filled with laughter. Jason and Mike arrived with slingshots and homemade cards. Martha baked a cake big enough to warrant its own zip code. Jennifer flew in from Ohio, hugging Mary like they’d survived the same storm.

David stood by the grill, flipping burgers with the seriousness of a surgeon. At one point, he came over and murmured, “Mary, you’ve taught me something. That family isn’t about who you share blood with—it’s about who you choose, and who chooses you back.”

Mary looked at Aiden, cheeks puffed as he blew out candles, eyes blazing with the light of survival and possibility. “I think he taught me that, too,” she said.

A New Family

That night, when the guests had gone and the kitchen was a battlefield of wrapping paper and crumbs, Aiden crawled into her lap. “Mom,” he asked, “are we happy now?”

Mary thought of cliffs and courts, of betrayals and verdicts, of nights when she thought survival was the only prize. She kissed the top of his head.

“Yes,” she said. “We’re happy. And we’re safe.”

Aiden grinned. “Good. Can we keep the no-cliff rule forever?”

“Forever,” Mary promised.

The Ending They Chose

Months later, Mary stood on the porch beside David, watching Aiden race his bike down the dirt road, cape flapping from his shoulders. He was laughing, and the mountains echoed it back.

“You’ve built something strong here,” David said quietly.

“We both have,” Mary answered, surprising herself by including him.

She turned her gaze upward. The cliff in Ohio had tried to erase her. Instead, it had carved her into something fiercer.

She whispered, more to herself than anyone, “True family isn’t about blood. It’s about love that refuses to let go.”

And inside, on the fridge, the House Policy list had one last line scrawled in Aiden’s block letters:

7. Joy is the best revenge.

Mary smiled every time she saw it. Because it was true.

Because they were proof.

Because they had chosen it.

News

My sister auctioned me and my son at her wedding, but someone raised their hand

Part One: Maple Street, Boston Winter comes early to Boston, walking in on people without knocking. By the first week…

My parents disowned me for getting pregnant… 5 years later, they saw my son

Part One: The Phone Call Maple Creek had the kind of mornings that made you forgive the rent. The town…

My obstetrician husband felt my sister’s baby bump – then demanded an ambulance

Part One: Maple Avenue in Autumn Columbus in October looked like a postcard someone forgot to mail. Maple Avenue wore…

At my sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me, calling me a single mother and a used product…

Part One: Numbers and Shadows The sound of calculator keys echoed in Aaron Johnson’s small home office like a quiet…

My mother-in-law sent me chocolate for my birthday, but my husband ate all of it…

Part One: The Birthday Box The heat in Boston didn’t knock; it moved in and asked what was for dinner….

James Corden Returns to U.S. Late-Night — And He’s Joining Former Rival Seth Meyers

After more than a year away from American late-night TV, James Corden is making his comeback. The former Late Late…

End of content

No more pages to load