Part One: The Phone Call

Maple Creek had the kind of mornings that made you forgive the rent. The town collected light the way an old frame collects dust, soft and spectral, and filtered it through brick facades and gingerbread trim. On Main Street, a Victorian with a proud second-floor bay window caught the sun like it had been practicing. At the top of that window, in old gold leaf that had withstood a century and several trends, the sign still read: BRADSHAW GALLERY.

In a worn walk-up kitchen three blocks away, Caroline Bradshaw stirred coffee in a mug that claimed, optimistically, Well-Behaved Colors Rarely Make History. She glanced up at the Victorian, a reflex she could never fully retire. Once, that building had meant childhood scavenger hunts between crates of paintings and the smell of linseed oil in October. Now it meant inheritance without invitation.

“Mom! I finished it.” Noah’s voice pinged off the cabinets, an overeager rubber ball.

He held out a piece of heavy paper two-handed, like an offering. A cat stared out from the page—green eyes with a problem to solve, whiskers stained by experience, a graphite shadow that turned fur into a question. The background was a wash of lowered afternoon. The cat looked like it had seen things and kept a few.

Caroline took a breath she hadn’t meant to. “Noah, this is wonderful.” She ruffled his curls. “It’s the one from the park, isn’t it?”

He nodded. “His eyes looked sad.”

There it was, the gift she recognized in him and had spent five years learning to hold without fear: the instinct to look under the surface and find the color that told the truth. She taped his drawing to the refrigerator beside a crooked heart, a paper snowflake missing a wedge, and a library reminder card with a stern due date.

“After breakfast,” she said, plating cereal and an overly earnest banana, “we’re going to my class. Special guest day—Ms. Louise, the clay magician.”

“Clay!” Noah shouted, and then, with sudden tenderness, “Can I make a home for the cat?”

“Absolutely,” she said. “Give him a front porch.”

Imagination had always been Caroline’s rebellion. Her parents had preferred ledgers to landscapes, valuation to value. They curated the prestige of Maple Creek’s oldest gallery with an ironed smile and an eye for the kind of art that doubled as a portfolio. Richard Bradshaw—sharp jaw, sharper sense of what played well at a donor dinner. Eleanor—gala chair, baton twirler for decorum, a woman whose compassion arrived on letterhead. Their younger daughter, Victoria, ICE graduate turned MBA, came back to town with a suit that appeared to cinch itself and slotted into the business like a missing gear.

Caroline had been the one who colored outside the revenue stream. She’d won high school shows and county fairs, earned the kind of teacher praise that lives in yearbook margins forever, and been told, with love that sounded a lot like threat, that art was a hobby and good families don’t budget for hobbies. “As a Bradshaw daughter,” Eleanor had said, handing her a brochure for a business camp that smelled like hotel carpet, “you must be practical.”

There had been a boy. Of course there had. Senior year, art room after school, a boy with paint on his hands and a last name that made donors purse their lips. David had wanted everything the way artists do before the world makes them edit: color, credit, credit lines. They’d found comfort in each other’s seriousness. It lasted until it didn’t, and then one inexpensive test in a pharmacy bathroom turned private promise into public disaster.

“Mom? Let’s go.” Noah already had his backpack on his shoulders like ambition.

“Let’s,” she said, grabbing her keys and her courage. In the small mirror by the door, she took stock: the riot of brown curls that refused tenure-track, the green-blue eyes that gave away more than they hid, the little line between her brows she’d made friends with. She lifted her chin, the way women do when history tries to speak over them.

The streets were awake. Maple Creek’s morning choreography featured a barista with tattoos of leaves on both forearms, a potter with a scarf that looked French and wasn’t, a dog who dragged its human past the bakery like it had a pretzel budget. As they turned toward the community art center, Caroline’s phone buzzed.

The name on the screen had the gravitational pull of a storm on the ocean. Victoria.

Five years since the last word. Five years since the night a cold living room and an iron declaration had shrunk the world. Five years since Victoria had slipped her a handful of emergency bills from a piggy bank and whispered an apology with eyes bigger than the truth.

“Mom?” Noah tugged, feeling the shift inside her without language for it.

Caroline answered. “Hello.”

“Caroline.” Her sister’s voice was the same… and not. Smoother, yes. But with a fretted edge, like a chord played longer than intended. “I want to talk to you.”

“What happened?” The question arrived before she could iron it.

“Can we meet? In person.”

No story wants to be texted. “All right,” Caroline said slowly.

“Tomorrow? Three o’clock? Central Park Café?”

Caroline looked toward the town green. The Bradshaw flag over the gallery lifted and snapped in a gentle breeze. “Tomorrow,” she said, and felt a tectonic plate shift inside her.

She hung up and kept walking because mothers do. Noah slid his hand into hers, warm and sure, and she thought, not for the first time, This is the safest thing I have ever done.

It is a strange thing about memory: it keeps showing you the same scene at different angles. That afternoon, while toddlers gloriously destroyed a table of tempera paint behind her and Ms. Louise explained the moral philosophy of glaze, Caroline’s mind opened a door onto seventeen again.

Two lines in a cheap plastic frame that meant one thing. The way the world tilted slightly out of true. The conversation that sat on her chest for a week, heavy, un-ignorable. The Bradshaw house a postcard of traditions as she walked in, the dining room set like a stage. Her mother’s voice first: “You’re late.” Her father’s paper folded with editorial scorn. Victoria at the table in a hoodie and an algebra problem.

“I have something to tell you.”

“About your grades?” Richard had asked without looking up.

“No.” Her throat had been a desert. “I’m pregnant.”

Freeze. Disbelief. Then heat. It was startling to remember what her father’s voice could do to a room. “Get out,” he’d said, and the word had broken something you don’t hear until it’s gone. Eleanor’s eyes had flamed. “The Bradshaw name will not be dragged through gossip by a… a child.”

“David and I—” Caroline had started, and the chorus had drowned her. That dropout. That family. We will take care of it.

“No,” Caroline had said, surprising them, surprising herself. “I want this baby.”

Her father had pointed at the stairs. “Then leave.” Final. “You are not my daughter.”

For thirty minutes, she’d packed like a person who’d read a bad checklist. In her room, Victoria had slipped in like disobedience, pressed money into her hand with shaking fingers, and whispered, “I’m sorry. I love you.” It had been the last kind thing that evening. After the front door, the cold had become a cathedral.

David had answered on the third ring, in a voice already on a train away. “I can’t,” he’d said. “My dad got me a scholarship. New York. Art school. I’m not… ready to be a father.”

She’d stayed in a phone booth until her legs forgot how to stand. Had you asked, she would not have been able to tell you how she made it to school the next morning. She knew only that the art room smelled like possibility and that Ms. Grace Anderson found her there and said, “You are not alone,” like a spell.

Grace had tucked her under a roof, steered her toward a community college, championed her through a certification, and told anyone who tried to pity her that Caroline was not a cautionary tale; she was a student, a teacher, a person who had chosen clarity and gotten burned and kept walking anyway.

Now, five years later, Caroline wiped a splash of tempera off a nineteen-month-old’s ear, graded a nine-year-old’s earnest dragon, and told a classroom full of small humans to “draw the sound sunshine makes.” She was solvent. She was exhausted. She was proud.

“Noah?” she called as she locked up at dusk. He sat by the picture window, little shoulders bent, the last light turning his curls into small fires. He held up his page: a mother and child walking through a park in October—leaves aflame, hands linked, faces drawn with an accuracy that made Caroline’s throat close.

“That’s us,” he said, unnecessarily, and Caroline did not cry because she had an agenda that included pizza.

“It’s a special day,” she said in the voice adults use when they are hiding a plot twist from themselves. “Cheese avalanche sound okay?”

“YEAH.”

They ate in a fortress of cardboard at the coffee table, the television murmuring an old cartoon in the background, and if every bite tasted a little like tomorrow, that was between Caroline and the ceiling fan. Noah narrated his day with an eloquence that would have delighted any editor: Jason had almost fallen off the big rock (“I caught him with my words”), Ms. Patel had said he “saw colors like feelings,” and he’d found a cloud that looked like a canoe for ghosts.

Later, when he slept a starfish across his small bed, Caroline sat at the desk by the window and opened a scrapbook. It was the kind of cheap album people buy for high school graduation parties and then forget. Inside were newspaper clippings—LOCAL TEEN TAKES FIRST IN COUNTY SHOW—and a few photographs that suggested families could be posed into almost anything. Her parents flanked her in one, in the gallery’s front room, smiles as wide and thin as admission. Caroline touched the gloss and felt the cool skin of a life she no longer claimed.

The next day, she left Noah at the studio early (“I’m in charge until Ms. Louise gets here,” he informed a bemused twelve-year-old with the gravity of a union rep) and walked alone to Central Park Café. The terrace was sunlit and a little chilly—New England’s favorite joke. She sat at a small round table and stirred her coffee with an anxiety that managed to leave a small whirlpool.

“Caroline.”

Victoria stood there like a photograph you can’t decide to keep or burn—more polished, yes, and more human, too. She wore an immaculate suit the color of intentions, and her eyes kept flicking to Caroline’s face like they were memorizing it for later.

“Vicki.” Caroline stood and then didn’t know whether to hug or shake hands or apologize for five years or demand an apology for five years. Victoria solved it by stepping in and hugging her, quick and real.

“You look well,” Victoria said.

“I make it a hobby,” Caroline answered, and when they laughed, the sound rearranged something precarious into something possible.

They talked weather, because weather can bear weight when people can’t. They talked about the town’s annual plein-air festival (“still too many straw hats,” Caroline said), and the community center’s new kiln (“no more Frankenstein pots,” Victoria said), and then Victoria’s breath hitched like someone tugging a kite.

“I’m getting married,” she said, the words wrapped in sunshine. “Next month.”

“Congratulations,” Caroline said, and meant it. “Who’s the lucky human?”

“James. James Harrington.” Victoria blushed like a choice and not an assignment. “He’s… kind.”

Caroline’s chest changed temperature. “That matters,” she said.

“I want you there,” Victoria said, and suddenly they were looking directly at the thing in the room. “Please. I don’t want to do it without you.”

“What about—” Caroline gestured vaguely toward a past that had excellent posture and a bad temper.

“Our parents want to reconcile,” Victoria said, and there it was: a word that had never graced their kitchen table. “Especially since Dad’s heart… he’s not well. He won’t admit it, of course.”

“Richard,” Caroline said, testing his first name the way she’d tested watercolor papers—seeing whether it could hold her resentment without buckling.

“And… James’s family expects… everyone,” Victoria added, wincing at the old politics of it.

“So,” Caroline said, keeping her voice from snapping, “you need a prop.”

“No,” Victoria said, quick, pained. “I need my sister. I want my sister. The rest is… noise.”

Outside, a golden retriever attempted to steal a bagel. Inside, a woman weighed mercy against math. Caroline watched a child fling himself down the slide across the park with reckless joy and thought about the price of erasing history and the price of recovering it. “What about Noah?”

“I’d like to meet my nephew,” Victoria said, and her eyes did a thing Caroline recognized from the night of the piggy bank. “I know we don’t… I know I wasn’t brave. I want to be now.”

Caroline picked up her cup and put it down again. “Let me think.”

Victoria nodded. “Of course. Soon, if you can.”

They hugged again at the corner, a careful choreography around everything unsaid. As they parted, Victoria handed her an envelope, thick for its size. “The invitation,” she said, then hesitated and produced a second. “And… this. They asked me to give it to you.”

Back home, after Noah fell asleep to a book about a duck who made impractical life choices, Caroline sat at the table and peeled open the second envelope like it might hiss. Inside, a check—more than she made in a year—and a note in a hand she had practiced emulating for perfect holiday place cards: Caroline—This is part of the trust you should have received. We can discuss the rest. —Richard Bradshaw.

Money is a language that pretends to apologize. It doesn’t. It does, sometimes, take the edge off the rent.

Caroline slept badly and woke certain. She texted Victoria: I’ll come. I’ll bring Noah.

Three days later, the past knocked on her front door. When she opened it, time pressed its face to the glass.

Richard looked smaller and grayer, as if someone had swapped him for an older actor and hoped no one would notice. Eleanor was immaculate as ever, but her eyes had laugh lines that hadn’t earned their name.

“Caroline,” Richard said, and the word sounded like he’d had to practice. “May we—?”

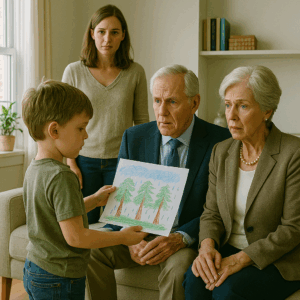

She found herself stepping aside. Noah sat cross-legged on the rug, surrounded by the cheerful carnage of markers and paper. He looked up at the newcomers, solemn as a magistrate. “Mom?”

“These are—” Caroline paused. Titles are contracts. “Your grandfather and grandmother.”

Something flickered in Richard’s face—astonishment, then pain. He moved forward slowly, like approaching a painting he was not sure he deserved to see. “What are you working on?” he asked.

“A forest after rain.” Noah held up the paper, and the room stopped talking. Greens layered over gray. A soft brilliance that had nothing to prove. Light becoming shape becoming feeling.

Richard took the drawing with hands that remembered. Eleanor leaned in, ring catching the light. For a split second, the Bradshaw gallery owner and the gala chair vanished, and Caroline saw two people standing before a color they remembered wanting and had told themselves they couldn’t afford.

Richard looked at Caroline, an apology tugging at the corner of his mouth like a word. He didn’t say it. Not yet. She wasn’t ready to hear it.

“Pizza?” Noah asked, because the world is merciful and gives us children who know when to fold a scene into ordinary life.

“Not tonight,” Caroline said gently. “Tonight we talk.”

There would be more. There would be a ballroom with chandeliers posing like swans and people who had opinions about salad forks. There would be a famous critic and a secret revealed like a thread pulled too hard. There would be a public apology and a private condition. There would be Christmas, and a doorbell at an inconvenient hour, and a man from a past Caroline had filed under Avoid.

For the moment, there was a living room that smelled like crayons and coffee, a boy who had painted rain into joy, and a woman who had learned to make a home that held.

Outside, Maple Creek moved its light from the Victorian bay window to the single bulb over Caroline’s stoop, and for the first time in five years, the gallery and the apartment seemed, from a certain angle, part of the same town.

Part Two: Family Exhibit

The apartment did what apartments do when history knocks—it tried to make itself smaller so everything would fit. Eleanor perched on the edge of the sofa with her ankles crossed like propriety could hold her upright. Richard stood by the bookcase, hands undecided, examining Noah’s drawings as if provenance might appear in the corner in neat block letters.

“Would you like tea?” Caroline asked, because hospitality is the rag you instinctively slap over a boiling pot.

“Yes,” Eleanor said too fast. “No sugar.” Then, catching herself, “Please.”

Richard cleared his throat, consulted the spine of a cookbook like it contained jurisprudence, and said, “You have… made a life.”

Caroline set cups on the table without ceremony. “That was the task at hand.”

Noah, who had moved from forest to an ambitious attempt at a harbor scene, glanced up with the frankness of five. “Do you like pizza?”

“I do,” Richard said, relieved by the question, grateful for a category he did not have to confess to failing. “I also like… landscapes.” He felt foolish as the sentence left the runway.

Eleanor looked at her husband sharply, then turned to Noah with a smile she’d borrowed from a better year. “I baked cookies,” she said, as if this constituted reparations.

Caroline sat, cup in hand. “You sent a check,” she said, folding the sentence gently enough to keep it from cutting. “Thank you.”

Richard nodded, eyes on Noah’s brushwork. “That was… overdue.” He hesitated. “As is this.”

“Words,” Eleanor said softly, without looking at him.

“Yes,” he said. “Words.” He lifted his gaze to his eldest. “Caroline, I—” He faltered, as if apology were a poem he’d never learned to scan. “I do not expect forgiveness because I have finally found my manners. But I was wrong. About art. About you. About what makes a family worth anything.” He sounded like he was giving a eulogy at a wake where the deceased was pride.

Eleanor’s hands trembled just enough to clink china. “I thought I was protecting you,” she said to her teacup. “Protecting the family. I hurt you instead.” She dared to glance at Noah. “I am… glad I was wrong.”

Caroline let the silence sit between them like a canvas, waiting. She did not rush to fill it. Noah solved the moment by holding up his paper. “The boats are sleeping,” he said gravely. “They dream of pancakes.”

“An understandable ambition,” Eleanor murmured, and everyone exhaled.

The meeting lasted an hour and a half because even penance has childcare constraints. They discussed logistics—wedding seating charts, ceremony length (Noah’s tolerance for speeches capped at three paragraphs), shoes. When they left, Richard paused in the doorway. “Thank you,” he said, and it sounded like an admission fee he was grateful to pay.

In the hush after the door closed, Caroline sat on the rug and let the room stop vibrating. Noah crawled into her lap, as precise about comfort as he was about line. “Are they really my grandpa and grandma?” he whispered into the weave of her sweater.

“They are,” she said. “And so am I.”

He leaned back to look at her. “What?”

“A person who belongs to you,” she said. “On purpose.”

He considered this. “Okay,” he said. “Can we have pizza now?”

“Absolutely.”

Harrington Plaza Hotel had opinions about chandeliers and made sure you were aware. The lobby smelled like money was burning somewhere pleasantly far away. Caroline felt the old itch to sketch the way light pooled on marble like spilled cream. Noah, in a small tuxedo he called his “spy suit,” gripped her hand the way astronauts grip instructions.

“Remember,” Caroline whispered, “if the speeches go long, you can draw the chandeliers into octopuses.”

“They already are,” he whispered back.

“Caroline!” Victoria swanned toward them in a dress that could have negotiated a trade agreement. She hugged her sister, then crouched to Noah’s eye level with a grin that made her look fourteen again. “Hello, sir. Thank you for coming to my party.”

“Congratulations,” Noah said formally. “Your dress is very shiny.”

“Thank you,” she said solemnly. “It makes me feel like a comet.”

Caroline laughed, and the sound ricocheted to the ceiling and back with approval. James—tall, kind-eyed, looking like the kind of man who learned apologies early and meant them—joined them and shook Caroline’s hand as if they were old friends. “I’m grateful you’re here,” he said simply.

“Me too,” she said, surprised to find that she meant it.

Richard and Eleanor approached with caution, not wanting to spook either daughter. There had been a few visits since the apartment, carefully choreographed, with Noah acting as both subject and buffer. Public was different. The town watched. The Harringtons watched with the curiosity of people good at reading ledgers and faces. Caroline felt herself stand straighter to meet the gaze. She had brought her own life to this room; she would not let this room shrink it.

The ceremony was crisp, speaking parts, a ring exchange, an ardent kiss that made the minister clear his throat theatrically. At the reception, Noah lasted twenty-two minutes of toasts before retreating to a sofa with his sketchbook. Caroline kept an eye on him while navigating well-meaning “we’ve heard so much about you”s like a slalom. Colorado cousins, college roommates, the mayor’s wife who always smelled faintly of lemon pledge. Everyone wanted a sentence.

Caroline was halfway through a conversation about summer camps with a woman whose foundation funded everything except joy when she heard it—a delighted bark from the sofa area: “This is remarkable.”

Joseph Harrington, known in the arts section as a critic whose star ratings could resurrect careers or burn them down for heat, bent over Noah’s book as if peering into a rare cabinet. He wore a bow tie that refused to be ironic and a smile rarely seen in print.

He gestured to a page. “Whose child?” He sounded like he was ordering discovery.

“Mine,” Caroline said, at Noah’s side in three steps. “And you are?”

“Joseph.” He flicked his eyes over her, not the way men do when they are deciding if you belong to them, but the way art people do when they are trying to place you within a family tree. “You’re Caroline Bradshaw.”

Caroline’s shoulders performed a complicated movement that might have been a shrug if it had been less honest. “Yes.”

“Ah,” Joseph said, as if something clicked. He turned the page back. Noah had sketched the ballroom in quick lines—the chandelier rendered as a jellyfish, the tables as lily pads, Victoria as a comet with a waist. The perspective was ambitious; the choices were fearless.

“The Bradshaw talent continues,” Joseph declared, then raised his voice slightly—trained, without being crass. “Richard! Come here a moment.” Heads turned as if someone had cue cards.

Richard hesitated, then crossed the room. Whispers followed—of course they did. Maple Creek could do gossip as an Olympic sport, artistic category.

“Your grandson,” Joseph said, tipping the book.

Richard looked. Something old and tender flared to the surface like a fish you didn’t think this lake still held. Caroline watched, arrested. Joseph misread and forged ahead. “Reminds me of your early landscapes.”

“His what?” Caroline asked, before she could edit the sentence.

Joseph blinked. “Surely you know that before he went full Cremona—excuse me, commerce—your father was a promising painter? Those dramatic marshes, the color sense…” He wiggled his fingers as if dispersing pigment. “Sacrificed the brush to take up the ledger. Crime against art, if you ask me.”

The air in the room leaned forward. A circle formed the way circles do—polite, ravenous. Caroline felt the peculiar vertigo of a child learning her parents had lives before she existed, except the child was grown and the lives felt like redacted files. She turned to Richard. “You painted.”

He swallowed. “I did.” His voice sounded like it had walked a long way without water.

“And you told me,” Caroline said, aware now of an audience and beyond caring, “that I couldn’t live on art.”

“I told myself that first,” Richard said. “Then I told you because it was easier than admitting I was afraid.”

“But why deny it?” Caroline’s voice didn’t rise; it went deep. “Why deny me? Why deny him?” She nodded at Noah, whose pencil paused mid-line without tearing the paper.

Eleanor reached for Richard’s forearm, fingers blanching. “This is a family matter,” she murmured, but the horse had left the barn and was standing at the microphone.

Joseph, to his credit, had the grace to step back into witness mode. The onlookers did not. They did what onlookers have always done; they listened with their ears and their mistakes.

Caroline inhaled. “I grew up in that gallery smelling varnish and hearing ‘practicality.’ You love the work. You love what it costs.” She didn’t make it a question.

“I love what it feeds,” Richard said, then caught himself. “Fed. Used to feed. God, Caroline, I—” He stopped, because there are sentences you can finish only when you are ready to change.

The whispers swelled—the oldest daughter; five years; a baby; did you know—and Caroline’s skin remembered the night she had left, the cold, the phone booth. She took Noah’s hand and turned to go because there were limits and she had learned them.

“Don’t.” The word came like a bell.

Victoria stood in the center of the room, comet dress blazing. She lifted her chin and raised her voice, not to a shout—she is not a shouter—but to the register of leadership. “This is my wedding,” she said, voice steady. “What matters to me is that my family is here. My whole family.”

She walked to Caroline and wrapped an arm around her shoulders, pulled in Noah with the other, and held them there like a statement. The room adjusted. James stepped to Victoria’s side, hand on her back, and nodded once to Caroline—an acknowledgment, a promise that he understood the weight and would not put it down.

There was a smattering of applause that turned into something warmer, not because people love a scene, though they do, but because some scenes tell them who they are supposed to be.

Richard approached as if the floor might fail. Public contrition is a genre with many bad examples. He did not attempt poetry. He faced his elder daughter and said, clear and low, “We were wrong.”

Eleanor stood with him, fingers laced with his. “We want a chance to do the right thing,” she said, and for the first time since Caroline could remember, Eleanor’s voice held no committee.

Caroline did not reward performance. She measured intent by muscle. “If you mean it,” she said, “you’ll show Noah who you are with your time, not your checkbook. You’ll open your studio, if you still know where it is. You’ll sponsor kids whose last names don’t buy them catalog space. You’ll stop using practical as a taxidermy word for afraid.” She squeezed Noah’s hand. “He gets to choose. So do I. So do you.”

Richard nodded once, oddly relieved to be given instructions. Eleanor nodded, less relieved, but firm. The crowd swallowed and turned back into a reception. Music restarted, softer at first, then reckless. Someone popped a bottle and forgot to apologize.

Joseph sidled to Caroline’s elbow. “Forgive an old man,” he murmured. “I did not intend to start act three.”

“You do that for a living,” she said dryly.

He chuckled. “True. Your boy—he is something special. You know that.”

“I do,” she said. “He’s a person, though. Not a headline.”

Joseph put up both palms. “Understood. If there’s anything the Harringtons can do to… invest in that personhood, say the word. Quietly.”

“Start with scholarships,” she said. “For the kids whose parents are afraid of color.”

He smiled. “Consider it done.”

Later, when cake had been cut and toasts exhausted and the comet had danced with the kindness man as if joy paid well, Caroline stepped onto the balcony to let her body decide how it felt. Maple Creek’s night air had edges; she welcomed them. Noah joined her, his tie askew, hair performing mischief.

“How did we do?” she asked him.

“We didn’t fall,” he said. “We danced.”

“That we did.” She straightened his tie. “How are the octopuses?”

“They’re full,” he said. “Of cake.”

They stood in companionable silence. Caroline thought about the word reconcile, which sounded like reconciling accounts and less like reconciling hearts. She decided she didn’t need reconciling. She needed repair. Those are not the same job.

Behind them, a door opened. Richard stepped out, something small and hesitant in his hand. “I found this,” he said, awkward, and offered a business card-sized scrap of thick paper: an old gallery postcard. On the back, in his younger hand, a study—marsh grass bending, light pretending to be water. “I kept a few.”

“It’s good,” Caroline said. “It makes me want to stand there.”

“Me too,” Richard said, then, after a beat, “again.”

She tucked the card into her clutch and nodded. “Then do,” she said. “Stand there.”

He laughed, surprised. “Bossy.”

“Just specific,” she said, and they both smiled for what might have been the first time in a decade without blinking against it.

Snow came late that year, as if the weather was checking its own calendar twice. By Christmas, Maple Creek had slapped a postcard overlay on itself—wreaths like green punctuation, shop windows fasting with paper stars. Caroline’s apartment, never large, performed Santa’s warehouse in a charmingly chaotic way. Under their small tree sat gifts from friends, neighbors, the community center… and two with From: Grandpa & Grandma written in Eleanor’s careful hand.

“Mom! Santa came!” Noah thundered from his room, a comet in fleece.

“He does that,” Caroline said, yawning, letting the coffee maker declare independence. She glanced around the living room. Six months since Victoria’s wedding, and the words we were wrong had not turned into an empty promise. Richard had pried open his old studio, aired it, and invited Noah in. Saturdays found them with coffee and charcoal, the boy’s small hand inside the larger one for a moment, and then away it went on its own. Eleanor had learned that parks do not stain, and that cards in Candy Land are not graded, and that apologies can wear mittens.

The doorbell rang at ten, as planned. Richard and Eleanor stood in the hall, cheeks pink, carrying gifts that were clearly not toys and therefore potentially interesting. “Merry Christmas,” Richard said, and there was comfort in hearing that ordinary sentence unburdened by record-keeping.

They were two gifts in when the doorbell rang again. Caroline frowned; unexpected visitors should be a spring holiday by decree. She opened it.

“Caroline.” The name came out breathy and familiar. David stood there in a coat that wanted to be a statement and hair that looked like it belonged to a younger scandal. He held nothing but a face full of entitlement.

Caroline’s first feeling surprised her by not being anger. It was assessment. The second was an almost comic awareness that she was, in fact, wearing Christmas socks. “No,” she said, and went to close the door.

“I have a right,” he said, pushing the edge, voice rising to find an audience. “He’s my son.”

“No,” she said again, calm as weather. “You had five years to find your rights when they looked like diapers and rent. You didn’t.”

He opened his mouth for a name he thought still belonged to him. “Cara—”

Richard’s silhouette filled the hall behind her, not dramatic, just terribly present. “You have no rights,” he said, and his voice made clear this was not about money this time, not about shame, but about a line. “Not legally. Not morally. Not in this home.”

David’s bravado wobbled. “I’ll go to the papers,” he bluffed. “Genius Boy’s Real Father Denied!”

“Be our guest,” Richard said mildly. “By all means, tell them the rest while you’re there. ‘Successful artist impregnates and abandons seventeen-year-old, neglects child support in several states.’ I’ve already spoken with a lawyer. She enjoys this sort of narrative arc.”

Something in David’s eyes did the math and got a smaller number than it had planned. He looked at Caroline, past her, toward the sound of Noah explaining Santa’s policy on pancakes. For a split second, something like regret flickered and failed. “You can’t keep him from me forever,” he said, but it came out whittled.

“I don’t intend to,” Caroline said softly. “One day, he can choose whether to know you. He will do it with the truth in his hand.” She closed the door gently because slamming would have felt juvenile. She leaned her forehead against the wood for a count of three, then turned back toward her family.

Richard and Eleanor looked at her as if she had performed a magic trick they had spent a lifetime insisting didn’t exist.

“I haven’t completely forgiven you,” she said quietly, settling on the arm of the sofa, watching Noah line up his new pencils by temperature. “But for Noah’s sake, and mine, I want to move forward. Little by little.”

Richard nodded. Eleanor nodded. Outside, snow began again, polite, insistent, making the town look cleaner than it was. Inside, Caroline breathed deeper than she needed to and let the room accept it.

Noah ran over and dropped into her lap, holding up a brand-new sketchbook. On the first page, he’d written in careful block letters: US.

She kissed his hair. “That’s right,” she said. “Us.”

He wriggled down and returned to his work. Richard reached for a pencil absently and then, catching himself, asked, “May I?”

Noah considered him with the gravity of a curator. “Yes. But no drawing over my drawing.”

“Understood,” Richard said, and bent to make a small line in the corner—two boats, side by side, headed in the same direction.

Caroline watched them, then walked to the window. Maple Creek’s street was dressed as hope. She lifted the old gallery postcard Richard had given her from the mantel and propped it beside a photograph of Noah on the swings. It looked less like history now and more like continuity.

In the kitchen, her phone buzzed with a new message from Victoria: We’re making lasagna. Come over tonight? Caroline typed: We will. Then, after a beat, We are.

She could not fix the past by making a better one. You don’t get extra credit for the future. But standing in her own small room, listening to her father’s low voice explain horizon lines to her son while her mother learned the names of all the dinosaurs in Noah’s book by pretending she didn’t already know them, Caroline felt the precise satisfaction of a frame finally hung level.

Outside, the Victorian on Main caught the light and threw it back into the street like confetti.

Part Three: Provenance

The New Year arrived in Maple Creek the way it always did: with wreaths losing patience, snow that pretended to be permanent, and the gallery on Main Street unveiling a banner in a font so ornate it looked apologetic.

But this year the banner said something unexpected.

NEW GENERATION: Emerging Artists of Maple Creek

For the first time in decades, the Bradshaw Gallery was not selling paintings as commodities or arranging retrospectives to flatter patrons. Instead, it was giving space to kids who’d painted murals on the sides of barns, to retirees who had finally picked up the brushes their parents had once made them put down, to Caroline’s students whose watercolor experiments still smelled faintly of grape juice.

Richard stood in the front hall of the gallery like a man re-learning how to walk. He had reopened his long-abandoned studio after Caroline’s challenge at Victoria’s wedding, dusted off jars of dried brushes, and spent December sketching marsh grasses the way he had at twenty. It had been both humiliating and liberating.

Now he was trying to prove, in public, that his gallery could be more than a ledger with frames.

Caroline wasn’t convinced.

She walked in with Noah at her side, both of them in coats dusted with snow. The main hall smelled of pine and turpentine. Along the walls were canvases labeled with names that had never been in Bradshaw brochures before: Emily S., age 10, Untitled (Fox). Thomas Rivera, 67, First Winter After Retirement. Noah B., age 6, Forest After Rain.

Noah’s drawing—blown up from the original, matted, carefully framed—hung at child’s-eye level on a small side wall. Caroline stopped in front of it, hands deep in her pockets, trying to suppress the mix of pride and protectiveness that roared inside her.

“Do you like it?” Noah asked nervously, as if his mother might suddenly disapprove.

“It looks like it breathes,” Caroline said. “That’s rare.”

Behind them, Eleanor approached with the cautious warmth of someone who knew she had used up her chances at effusiveness. “We wanted Noah to have a place here. Not because of the name. Because of the work.”

Caroline glanced at her mother, eyebrows arched. “A distinction I never thought I’d hear you make.”

Eleanor didn’t flinch. “I’m learning.”

Richard joined them, holding a program he had clearly edited too many times. “It matters that people see. Not just Noah, but all of them. That’s the correction I can make.”

Caroline looked around. The gallery was full, not with the usual donors in pearls, but with townspeople in snow boots, teenagers with cameras, a handful of elderly couples who looked like they’d been waiting for this for forty years. For once, the chatter wasn’t about auction estimates. It was about color.

“Keep doing this,” Caroline said flatly. “Not once. Not for appearances. For real.”

Richard nodded, and for once he didn’t try to argue.

The Studio

Saturday mornings became ritual. Richard, still stiff with age, let Noah invade his reopened studio with the kind of generosity that can only come from guilt turned into usefulness. They stood side by side at easels, the boy sketching fast and fearless, the grandfather pausing too much before each stroke.

“Don’t think so hard,” Noah would scold. “Just do.”

Richard chuckled. “I used to be told that. I didn’t listen then, either.”

Caroline would hover at the doorway, arms folded, not interfering. She didn’t trust this sudden transformation, but she couldn’t deny that Noah adored it.

Eleanor found her role in smaller ways—baking muffins Noah devoured, organizing the gallery’s new scholarship fund, spending afternoons in the park teaching him the names of birds. She was still precise, still Eleanor, but her edges softened around Noah in ways that surprised everyone, including herself.

David’s Ghost

In late January, a small notice appeared in the Boston Globe: Artist David Cole Accused of Child Support Evasion Across Multiple States.

Caroline read it once, then once again, her tea cooling beside her. The article mentioned lawsuits, delinquent payments, “a pattern of abandonment.” She folded the paper and put it away.

When Noah asked, “Did my dad make art like me?” Caroline answered, “Yes. But he didn’t know how to take care of the people he loved. That matters more.”

Noah nodded solemnly, as if filing it away for future reference. “Then I’ll do both.”

“Exactly,” Caroline said, and kissed his hair.

The First Show

In March, Caroline’s students were invited to display at the gallery’s spring event. For some, it was the first time their work had been seen outside of a classroom. Parents came with phones, siblings clapped too loud, one child cried at the sight of his painting in a real frame.

Caroline stood in the corner, watching, realizing she was proud not just of Noah but of all of them—the messy brushstrokes, the strange colors, the wild imagination that refused to apologize.

Richard approached quietly. “You’ve built something I never could.”

“You could have,” Caroline said, not unkindly. “You just chose differently.”

He nodded. “I want to choose better now.”

Caroline considered, then said, “Better is daily. Not dramatic. Daily.”

“I understand,” Richard said, and for once she believed him.

Spring, and a Test

April brought thaw and mud and an unexpected invitation: a juried regional show at a nearby college. The organizers wanted to include one child’s piece to represent “emerging talent.” They had seen Noah’s Forest After Rain in the local press.

Caroline hesitated. She didn’t want Noah to become a commodity, didn’t want his gift to be turned into currency. But she also didn’t want to hold him back out of fear.

She asked Noah. “Do you want strangers to see your work?”

He tilted his head. “Will they like it?”

“Some will,” Caroline said. “Some won’t. That’s how art works.”

“Okay,” he said. “I want to try.”

At the show, Noah’s painting hung beside landscapes by college seniors and sculptures by faculty. People stopped in front of it, surprised. A local reporter took his picture. Noah beamed, then looked up at his mother and whispered, “Can we get ice cream now?”

“Yes,” Caroline said, laughing. “That’s the right priority.”

Seeds of Forgiveness

By summer, Caroline’s apartment walls bore fewer ghosts. Family dinners with Richard and Eleanor became cautious but consistent. Victoria and James visited often, bringing warmth and steady humor. Noah thrived, still innocent but now girded with a sense of belonging that didn’t rely on illusions.

On the Fourth of July, the Bradshaw family stood together in the town square, watching fireworks scatter color across the sky. Noah sketched them fast in his notebook, capturing not just the bursts but the gasps of the crowd.

Caroline glanced at her father. He was watching Noah, not the fireworks, his expression equal parts pride and penance.

She thought: This is not forgiveness. Not yet. But it’s something sturdy enough to stand on while we try.

Ending

On a late-summer evening, as light bent gold across Maple Creek, Caroline taped a new rule to her fridge, written in her own hand beneath Noah’s scrawl of “US”:

House Policy #8: Joy is not a hobby. It’s the work.

She stepped back, looked at the list, and smiled.

Because she had learned that family could fracture, but it could also repair—not perfectly, not without cracks, but with enough strength to hold new weight.

Because she had learned that art was not just survival—it was proof of it.

And because she had learned that sometimes the gallery you inherit isn’t a building at all, but the people who stand with you, flawed and willing, under the light.

Outside, the Bradshaw Gallery glowed in the evening sun, its new banner fluttering. Inside her apartment, Noah laughed at a cartoon, pencil in hand.

Caroline lifted her coffee mug, toasted no one and everyone, and thought: This is the exhibition that matters.

News

My obstetrician husband felt my sister’s baby bump – then demanded an ambulance

Part One: Maple Avenue in Autumn Columbus in October looked like a postcard someone forgot to mail. Maple Avenue wore…

My parents and sister pushed me and my 6-year-old son off a cliff.

Part One: The Hike Willowbrook, Ohio was the sort of town that made postcards feel like they’d been eavesdropping. Spring…

At my sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me, calling me a single mother and a used product…

Part One: Numbers and Shadows The sound of calculator keys echoed in Aaron Johnson’s small home office like a quiet…

My mother-in-law sent me chocolate for my birthday, but my husband ate all of it…

Part One: The Birthday Box The heat in Boston didn’t knock; it moved in and asked what was for dinner….

James Corden Returns to U.S. Late-Night — And He’s Joining Former Rival Seth Meyers

After more than a year away from American late-night TV, James Corden is making his comeback. The former Late Late…

Greg Gutfeld Says Late Night Ignored Viewers — and He Cashed In: ‘There Was Free Money on the Table

Greg Gutfeld has never shied away from stirring the pot. The Fox News personality turned late-night disruptor is once again…

End of content

No more pages to load