I had thought it would be another calm week. My daughter, Lucy, thought it would be the best one yet. She was half right.

Every summer since she turned four, I dropped Lucy off for what my parents branded “Grandma Week.” It sounded like a tradition with lemon bars cooling on the counter and a lawn sprinkler making rainbows, a week that belonged to childhood. The truth was less postcard and more ledger: birthdays remembered when there was a camera, promises honored if they looked good in a frame. My parents liked things that read as family from the street—balloons, casseroles, grandparent titles—less so the parts that required midnight patience and the steady hum of responsibility. Jenna’s kids, Aiden and Sophie, soaked up most of the attention that survived the photo ops. That was the rhythm I grew up to, learned to dance around, and eventually mistook for love.

I told myself a week with cousins would be good for Lucy, good for her sense of family, even if mine had always felt like an obligation you signed with your last name.

Their town sits roughly ninety miles from ours—close on a map, farther in the body. Every time I drove there, something in my chest went tight, the way it does when you pass your old school and instinctively check if the windows are looking back. The driveway creaked the same way it did when I was twelve. The porch light had been upgraded to a smart bulb, but the welcome mat still announced a cheerfulness the living room rarely delivered.

“Grandma!” Lucy yelled before I had even shifted into park. She was already unbuckled, vibrating, small sneakers drumming the floorboard like a heartbeat I was about to miss.

My mother stood under the porch awning, one hand shading her eyes as if sunlight required manners. “Well, there’s my favorite girl,” she said, arms open. She meant Lucy, not me. That’s a detail I no longer pretend is incidental.

On the lawn, Aiden and Sophie ran through the sprinklers, shrieking in loops. Travis—my sister’s husband, a man who could hold a beer like it was a job—half reclined on a patio chair, performing helpfulness by proximity. The picture, if you didn’t know any better, looked like a catalog’s idea of summer.

Mom kissed the top of Lucy’s head. “She’s fine with us, Alice. You look tired. Take the week. Rest.” The kind of concern that points at you but never reaches you.

“I always do,” I said, and watched my girl tear toward the grass. Her laughter folded into the water sound and disappeared into the bigger noise.

For once, I let myself believe in the postcard.

My husband and I left the next morning for a short business trip we’d planned months in advance to overlap with Grandma Week. We run a small design company. The trip was supposed to be easy: two client dinners, a few meetings, maybe a single night of sleep without alarms. We were gone less than twenty‑four hours when the seams began to show.

I called that evening to check in. Mom answered on speaker. The house sounded busy in the background—dishes, the cousins, the bounce of a ball on hardwood.

“She’s right here,” Mom said, and then Lucy’s voice arrived, bright and breathless. “Hi, Mommy! We made cookies.”

“Good,” I said, smiling into a hotel bathroom mirror. “Be good for Grandma.”

Everything sounded fine, like a commercial for reassurance.

The next afternoon, my calls went unanswered. Once. Twice. After dinner, still nothing. By the time I opened social media, I had composed a dozen harmless explanations: phone charging; bad reception; hands full of crafts; too much fun to answer. I scrolled in the kind of denial that feels responsible.

Then the pictures found me—the kind that throw your stomach to the floor. Mom and Dad, Jenna and Travis, the cousins. Sun on lacquered smiles, wind in everyone’s hair, a yacht bouncing like a shiny promise behind them. The caption read: “Family trip. Finally, some time together.”

Family trip.

I stared until the screen blurred and my pulse made a noise in my ears. I scrolled back up, slower, as if Lucy might materialize if I gave the app time to think. No pigtails. No pink swimsuit. No Lucy.

I called my mother. She answered on the second ring, cheerful, the way people are when the world agrees with their plans. “Hi, honey. How’s your trip?”

“Where’s Lucy?”

“At the house,” she said.

“At your house?”

“Yes, dear. We couldn’t bring everyone. There wasn’t room in the car.”

“You left her there.”

“Oh, don’t sound so horrified. We asked the neighbor to check in.”

“What neighbor?”

“The one with the dog.”

“They all have dogs, Mom.”

She sighed, already bored with my failure to be grateful. “She’s fine, Alice.”

I hung up. It wasn’t dramatic. It was surgical.

My husband looked up from his laptop. “Everything okay?”

“No,” I said. “They left her.”

He blinked, frowning. “Left who?”

“Lucy. Alone.”

For a second he didn’t understand. Then his mouth opened and no sound came out. “Wait. What?”

“Mom said there wasn’t room in the car.”

He shoved his chair back so hard it barked against the floor. “You’re joking.”

“I wish I was.”

“Call someone. Call anyone,” he said. “We—”

“I’m calling Grandma.”

My grandmother answered on the first ring. “Sweetheart.” Her voice is sugar and iron at once. “Grandma.” The word cracked in the middle. “They went on vacation. They left Lucy alone.”

Silence. Then the rustle of keys. “What?” She did not ask for clarification so much as confirmation she could weaponize.

“At their house. They said a neighbor’s checking in, but I think that’s a lie.”

“She’s six,” Grandma said, sharp like a gavel. “What do you mean they left her?”

“I don’t know. Please. Can you go now? You’re the only one close.”

“I’m leaving right this minute,” she said, like a dispatch. “Stay on the line if you can.”

I stood by the hotel window and pressed my forehead to the glass and counted breaths that didn’t help. Twenty minutes crawled by, each one a mile of road under Grandma’s tires. Then her voice came back, breathless. “I’m here. I found her.”

Relief and nausea hit in a single, destabilizing wave. “Is she okay?”

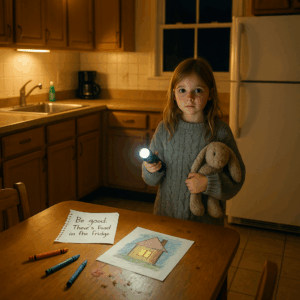

“She’s scared,” Grandma said. “She’s been eating chips and crackers. The lights are all on. She said she didn’t want the dark to come back.”

I pressed a hand over my mouth, an instinct older than language. “Thank you.”

“I’ll stay with her until you get here.”

We were on the first flight out in the morning. We dropped everything—clients, meetings, a booked‑solid calendar we’d spent two months building. The business could wait. Lucy could not. My husband didn’t argue. He packed before I finished the sentence. The night was long and the airport louder than usual, or maybe that was just the sound of my own decisions catching up. The plane climbed through clouds and I hated every minute we were above the ground.

Grandma met us at the door of my parents’ house as if she had been standing guard all night, which she had. “She’s inside.”

Lucy sat on the couch wearing one of Grandma’s sweaters, the sleeves bunched at her wrists like armor. Her eyes were too wide. The moment she saw me she launched from the cushions and ran until she collided with my ribcage. “Mommy.” I could feel her heart slam against mine. “You’re safe,” I said into her hair, which smelled like someone else’s laundry detergent and a little like fear.

Grandma’s voice was low and controlled in that way that means the floor is lava. “They left her a note.” She held up a square of lined paper like evidence: Be good. There’s food in the fridge.

I didn’t know what was worse, the note itself or how normal it tried to sound, like they were leaving directions for a house sitter, not abandoning a child.

The kitchen told the truth the note tried to mask. Crumbs, empty wrappers, a sticky trail of juice across the table like a map nobody followed. On the tabletop: Lucy’s drawing pad. A small stick figure in a house filled with yellow scribbles, every window colored in. All the lights still on.

Grandma put a hand on my shoulder. “You always believed they’d change,” she said softly. “Now you know.”

Lucy cried herself empty and fell asleep in the dent of the couch, cheeks hot, breathing irregular like she was practicing storms. Sometime near morning, she stirred and whispered, half in a dream, “I left the lights on so you’d find me.”

I stared at the hairline crack in the ceiling—the same one from when I was her age. It had widened, I think, or maybe I had just stopped pretending not to see it. Trust, it turns out, is plaster. It looks whole until the next tremor.

We drove straight to the police station after coffee we didn’t taste. The officer at the desk listened while I explained, pen dragging like he wanted the ink to hurt. “So she was alone for how long?” he asked.

“Half a day,” I said. “They left that morning for a week‑long trip. They planned to leave her the whole time. I called my grandmother when I figured it out. She got there that evening.”

He kept writing, slower now. “Unbelievable,” he muttered in a register that sounded like a father. I handed him the note. He read it and his mouth made a flat line. “We’ll open a welfare investigation.”

“Do you want me to remain anonymous?” I asked. He was already shaking his head when I said, “No. They need to know exactly who called.”

By the time we left the station, the sun was sliding down the sky and everything cast a long shadow that made the suburban sidewalks feel theatrical. We packed Lucy’s things quietly—her backpack with the two stuffed animals, the flashlight, the exactly eleven crayons she had counted like currency—and cleaned what we could. Grandma kissed her forehead. “You’re safe now, sweetheart,” she said. “And I will always come if you need me.”

“Promise?” Lucy asked, a small hand on Grandma’s wrist like she was sealing a contract.

“Promise.”

We drove home in a hush that wasn’t peace. Every few miles my husband’s hands would tense on the wheel, then release, like his body kept testing the brakes on a hill we couldn’t see.

A week later my phone lit up with Mom’s name. I put her on speaker so my husband could hear me not apologize.

“Hello,” I said.

“What did you do?” she asked, furious, not confused. The opening line of someone who already knows the answer.

“I filed a police report,” I said. “For abandonment.”

“What? What police report?”

A shuffle on the line and Jenna’s voice sliced in. “Don’t lie, Alice. We’re not talking about that.”

Then the chorus: both of them at once, outraged, louder than the facts. “What did you say to Grandma? She’s lost her mind. She’s giving the house to you. She’s throwing us out. You think that’s funny?”

I blinked and leaned back into the chair like distance could improve reception. “Wait… what?”

“Don’t act innocent,” Jenna snapped. “Grandma changed the trust. The house is in your name now.”

I didn’t even know the legal architecture behind my childhood—how the roof I stood under had belonged to Grandma’s revocable living trust and how, once, long ago, when my parents got married, Grandma had moved to the smaller house and made theirs ours with a signature. The story endings we inherit are always written in handwriting we don’t recognize.

“Sure,” Mom said, sarcasm slick and practiced. “You just happened to end up with the house. How convenient.”

“She’s not confused,” I said. “She’s angry. There’s a difference.”

“Angry because you filled her head with lies,” Mom shot back. “You’ve been jealous since you were a kid.”

“Of what, Mom?” I asked, too tired to play nice. “Your parenting or Jenna’s trophies?”

Her breath caught. Jenna returned, volume turned up. “You’ve destroyed this family.”

“No,” I said. “You did that when you left a six‑year‑old alone with a refrigerator.”

The line went dead with a finality that sounded like a slammed door.

My hands were shaking when I called Grandma. She answered like she’d been waiting.

“I was expecting this call,” she said. “I just got off the phone with them.”

“They’re saying you changed the trust.”

“I did.”

“Why?”

“Because I’ve spent seventy‑eight years cleaning up other people’s messes,” she said. “This time I wanted to prevent one.”

“They think I made you do it.”

“I know. They came by already.”

“They did?”

“Yes. I told them to leave. Then I called my lawyer.” Her voice was brisk, like she had rearranged kitchen cabinets this morning and legal documents this afternoon. “I’m fine. They won’t try again. They hate inconvenience more than consequences.”

I laughed, the kind that sounds like a cough. “They’re calling it elder abuse.”

“That’s new,” she said. “At least it’s creative.”

“Grandma… why give me the house?”

Silence breathed once down the line. “Because I can’t leave it to someone who thought the roof was fit for a child to be alone under,” she said. “It’s my decision, Alice. You don’t owe me thanks.”

“You’re sure?”

“I’m sure. Now promise me one thing: don’t let them near Lucy again.”

“I promise.”

“Good. Then we’re done worrying.”

On paper, that day looked like justice. In my body, it felt like exhaustion. Maybe families like ours don’t break all at once. Maybe they crack along the same seam, over and over, until someone bothers to look down and realize the floor is not a floor anymore.

For three days the phones stayed mostly silent. The kind of quiet that feels borrowed, like the pause between thunderclaps when you can’t tell if the storm is leaving or catching its breath. Lucy went back to school. My husband dove headfirst into spreadsheets. I tried to do laundry, answer emails, pretend the ceiling in our kitchen wasn’t suddenly fascinating.

On the fourth morning the quiet broke. Not with a knock at the door but with a cousin in Ohio who never calls. “You haven’t seen it?” she asked, stretching the words like they needed warming up.

“Seen what?”

She hesitated. “It’s online.”

She didn’t need to explain. Within minutes my phone was a slot machine paying out screenshots and links. My mother had posted a long paragraph with trembling verbs about betrayal and manipulation. Jenna added a shorter one: family loyalty, snakes in the grass, prayer‑hand emojis. Travis, who thrives in comment sections, wrote “#ElderAbuse” like a kid with a spray can who just learned a new word.

By lunchtime my name was trending locally. That’s a sentence no one wants to own without a publicist.

I called Grandma. She picked up on the second ring. “Something about computers,” she said before I could speak. “They called me. I told them I don’t do that Facebook nonsense.”

“It’s not nonsense,” I said. “Okay, it is. But they’re lying about you.”

“What are they saying?”

“That I made you give me the house.”

She snorted. “That’s creative. I can still think.”

“Do you want to see what they posted?”

She hesitated just long enough to make me hope she’d say no. “Might as well,” she said. “I hate when people describe things badly. Show me where to type.”

I drove the hour and a half to her place. The small house she’s had for three decades smelled like tea and clean air, the way it has since the day she left her big house to my mother and moved here with a single suitcase and a plan to outlive everyone’s theatrics.

“Write down my passwords,” she said when I set the laptop in front of her. “In case this kills the computer.”

“It’s not going to kill the computer.”

“You don’t know that.”

She leaned close to the screen and squinted at photos she didn’t remember authorizing. “Good Lord, they used my wedding picture. Where did they even get that?”

“Probably Aunt Carol’s endless album of family mistakes,” I said.

Grandma scrolled. Mom’s post had sighs and Bible verses and a tone that suggested she had been robbed of her own life by her ungrateful daughter—me. Jenna had written an essay about loyalty. Travis had tried on a lawyer voice like an ill‑fitting suit, arguing points that wilted in the sun.

Grandma’s hand trembled once and then steadied. “All right,” she said. “Enough fiction. Let’s tell the truth.”

“You don’t owe them anything,” I said.

“I owe myself a good night’s sleep,” she replied. “Now, where do I type?”

Her post was short, clean, and sharp, the way a good stitch closes a wound. She wrote: I changed my will and my revocable living trust. I did it because my daughter and her husband left their six‑year‑old granddaughter alone in the house I own while they went on vacation. I found the child myself that evening. No one tricked me. I’m not confused. I’m angry, and I’m done. The big house will go to Alice, who remembers what family means. The others can find another roof.

She hit Post, closed the laptop like she had adjourned a meeting, and said, “There. Now they can chew on that.”

The reaction was immediate. Within an hour her words were everywhere. People I hadn’t heard from in a decade texted me variations of Your grandma’s a legend. Mom deleted her post. Jenna locked her profile. Travis tried to argue and got eaten alive by the town’s collective memory. Grandma watched like someone observing a chess match she’d already won.

“They always forget,” she said, “that I raised half this town.”

Two days later Jenna showed up at Grandma’s door with flowers and sunglasses and a look that hoped to be mistaken for remorse. Grandma did not open the door. She watched through the window until Jenna set the carnations on the step. Then she waited another hour and threw them out.

“She brought carnations,” Grandma told me on the phone. “You don’t apologize with carnations. That’s like saying sorry with a parking ticket.”

That weekend my husband, Lucy, and I drove to see Grandma. Her house felt like a different country—quiet, steady, governed by rules that favored truth over performance. She had baked cookies. Lucy sat on the rug with a box of markers and drew houses with lights on in every window while we drank tea.

“They’ve been calling again,” Grandma said, too casually. “I let it go to voicemail.”

“What if they show up?” I asked.

“I’ll call the police,” she said. “And maybe the newspaper. They like updates.”

I laughed. “You really don’t scare easily, do you?”

“Not anymore. I already outlived their approval.”

When we left, she walked us to the door. “If they show up again,” I said, “call me first.”

“I’ll call whoever gets here faster,” she said, and winked at Lucy. “Don’t tell anyone I’m brave. It ruins my reputation.”

At home that night I scrolled through Grandma’s post again. The storm had mostly moved off, but the truth sat there, pinned at the top like a scar that healed on its own terms. One comment stood out: Sometimes the loudest families get quiet when someone finally tells the truth.

They wanted Grandma’s silence. She gave them the truth instead—loud, public, permanent.

Six months later, the paperwork had finished doing what it does: moving slowly, making facts official. My parents, Jenna, and Travis moved out of the big house when their thirty days were up. They rent now, altogether, in a duplex near the highway. No more yachts, no more “Family trip!” captions. Rent does that to people. The police investigation into the week of lights culminated in a charge of child endangerment. They received probation, a fine, and mandatory parenting classes. No jail. On paper that felt light; in the court of the town it was a headline that wouldn’t die. The report made local news, and suddenly everyone’s favorite family became the example parents used at dinner to explain why you check twice before you leave a driveway.

Child Protective Services knocked on Jenna and Travis’s door, a routine welfare check in name, but embarrassing enough that Mom couldn’t spin it into a victim story that lasted more than a day. From what I hear, their place is loud with fighting and quiet with resentment. I don’t call. They don’t either. Silence, it turns out, can be a peace treaty you sign with yourself.

Lucy and I visit Grandma every week now. The drive is an hour and a half of car karaoke and snack crumbs. She pretends to hate the noise and then waves from the porch before we’ve even pulled into the driveway, a hand already in the air like she started greeting us an hour ago. We’re planning a short vacation together this spring. Somewhere sunny, somewhere simple. Lucy has already packed three books and a swimsuit. Grandma says she’ll bring crossword puzzles and sunscreen “for the pale ones.”

Life has gotten small again in the best way—steady, quiet, honest. The kind of small that makes room for what matters. When Lucy falls asleep now, she does it with the lights off and the door cracked, the way children who trust the night do. Sometimes, when I’m cleaning up markers or folding sweaters a size too small, I picture that drawing she made—the one where every window in the house glowed with yellow—and I count the ways we learned what light is for: not for pictures, not for captions, but for finding your way home.

I don’t tell the story to make a point on the internet. I tell it because the truth is a kind of housekeeping. You say what happened. You put things back where they go. You turn off the lights when you leave a room.

As for the house that started the war—the big one with the porch where my mother shaded her eyes and called me tired—its deed now has my name. But houses remember who loved under their roofs. When the papers finally recorded the transfer, I didn’t celebrate. I drove past and kept going. I don’t know yet what I’ll do with it. Sell it. Keep it. Strip it down to studs and let the walls breathe. Maybe one day Lucy will run through those sprinklers again and no one will turn away to pose for a camera. Maybe not. For now it is enough to know the roof held when the lights were on.

People ask if I regret filing the report, if I regret Grandma’s post, if there was another way that did less damage to the storybook version of the people who raised me. I understand the impulse. We were taught to preserve the picture. But here is what I keep: a child who left the lights on so we would find her; a grandmother who drove into the dark without asking permission; the sound of a door that did not open when an apology arrived wearing sunglasses and carnations; the quiet of a house where the truth lives without explaining itself.

Maybe families like ours don’t fall apart. Maybe they finally align with reality. Maybe the unraveling is just the thread that never belonged coming loose at last.

On a Tuesday not special for any reason, I watched Lucy in the rearview mirror as we drove toward Grandma’s. She was drawing a house again, a new one, with windows the color of honey and a little stick figure standing on the steps. “Is that you?” I asked.

She shook her head and smiled. “That’s Grandma,” she said. “I’m the light.”

I turned onto the highway, the sky doing the pale blue thing it does when it’s decided not to rain, and for the first time in a long time I believed the road would take us somewhere good. Not because the past had been rewritten, but because we stopped trying to make a picture behave like a promise and finally let the truth do what it was built to do.

We didn’t shout. We did the right thing. And the next day, what had been built on performance began, at last, to come apart.

There are parts of this story I left at the edges the first time I told it, the way a camera pretends not to see a crack in the wall while the light does. Expanding the frame doesn’t change what happened; it only lets you see the grain in the wood, the fingerprints on the glass, the way the room remembers who raised their voice and who lowered it.

In the weeks after everything broke open, I became a collector of small, precise details, as if accuracy could be a kind of mercy. I kept a notebook in the kitchen drawer and another in the glove compartment, places you reach without thinking. I wrote down the exact time the airline gate agent called our zone to board and how the man two rows up swore under his breath when the overhead bins filled. I wrote down the way Lucy’s sweater smelled faintly of my mother’s dryer sheets, a scent that always tried too hard. I wrote down that the note on the kitchen table was on lined paper torn from a spiral notebook, the top edge still wearing the white confetti of its escape.

The truth likes specificity.

I keep going back, in my mind, to the evening before the drop‑off. The backpack on Lucy’s bed looked like a tiny expedition. She spread out her supplies like a museum exhibit and narrated each choice with the seriousness only a six‑year‑old can summon. “Two stuffed animals,” she said, arranging them face up so they could breathe. “The flashlight in case the power goes out. Eleven crayons because eleven is my good luck number.” She counted them slowly—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink, brown, black, gray, white—tapping each one to the cadence of her own conviction. I didn’t correct her on the math of luck. I only watched, memorizing her calm.

On the drive to my parents’ house, the highway stripes flicked past like a metronome for thinking. It was late June, the kind of evening that lingers on the skin. My husband drove while I pretended to read emails and actually rehearsed the ritual of goodbye. Lucy kicked her feet in the back seat and asked every few miles if sprinklers would be involved. We passed a billboard with a smiling family in matching polos advertising summer at the lake. I caught myself checking whether the mother’s face was turned toward the camera or toward her children. Toward the camera.

When we pulled into the driveway, my mother’s porch posture was textbook: one hand lifted to shade her eyes, the other opening to welcome the lens. “There’s my favorite girl,” she said, and I wondered, as I often do, whether people hear themselves when they practice a line so many times it becomes breath.

What I didn’t say then is that the yard smelled like cut grass and gasoline and the faint chemical cheer of sprinkler water. I didn’t say that Travis’s chair left two dents in the lawn like proof of a weight that never lifted. I didn’t say that the sound of Lucy’s sneakers hitting the pavement—slap, slap—made me feel both proud and unnecessary in the same beat.

The call from the hotel bathroom the next evening deserves its own paragraph in the permanent record. I can still see the chrome faucet and the way hotel lighting makes people look hopeful and tired at once. “She’s right here,” my mother said, and then Lucy’s voice filled the tile. “We made cookies.” If you could isolate that sentence and put it under glass, you might mistake it for safety.

The second day, when my calls went unanswered, denial came dressed up as logic. Maybe they took the kids somewhere with spotty reception. Maybe the cousins were playing a game where the rule was no phones. Maybe my mother finally decided to exist in a moment she wasn’t narrating. Even my husband, who is allergic to magical thinking, said, “Let’s give it an hour,” because love makes gamblers of all of us.

By the time the yacht photos lit up my screen, I had already talked myself out of every darker possibility. The image did not ask for interpretation. Sun spilling off water. My family in the middle of it. The caption’s exclamation points like confetti at the end of a sentence that didn’t include all the nouns. Family trip. As if the definition of family were bendable enough to stretch over a child left behind.

I have replayed my mother’s voice in that phone call—how cheer blooms into condescension when she believes she is right. “At the house,” she said, as if location were the only variable that mattered. “There wasn’t room in the car.” As if math, not choice, stood between Lucy and the back seat. As if the solution to arithmetic had ever been abandonment.

There was a moment, after I hung up, when my body moved without my permission. I was out of the chair, across the hotel room, hand on the window, forehead against glass. The city below us went on being a city. A siren wailed three blocks over. A couple in evening clothes argued quietly on the sidewalk. Somewhere a dog barked like a metronome for someone else’s panic. I remember thinking, absurdly, that if I could make the world hold still for thirty seconds, I could rewind time to the driveway and put Lucy back in the car.

Grandma answered on the first ring like she’d been standing beside the phone waiting for purpose. She did not make me say the words twice. “I’m leaving right this minute,” she said. The call did not turn her into a different person; it distilled who she already was.

I listened to her car eat distance. She kept me on the line but she didn’t waste breath narrating turns. Once, when a truck swerved, she cursed and apologized to no one. When she pulled into my parents’ driveway, I knew it by the silence that happens when an engine cuts and a decision begins. “I’m here,” she said, and then, seconds later, “I found her.” If faith were a thing you could hear, it would sound like that.

Lucy’s description of those hours lives in small, careful sentences. “I turned on all the lights,” she told me later. “The fridge said beep when it was open too long. I closed it so it could be happy.” She lined up crackers on a plate and ate them in pairs, because pairs felt like company. She sat on the couch and watched the door and counted the spaces between the sound of cars. She drew a house with windows the color of morning and put herself inside it so she could be both safe and seen.

The flight home did not care about our urgency. Planes are democratic that way. The seatbelt sign blinked on for a turbulence patch that felt like God shaking a tablecloth. My husband kept checking the time and subtracting and subtracting until there was nothing left to do. The flight attendant who offered water saw something in my face and did not say the polite thing people say; she only touched the plastic cup to my hand and moved on.

At the house, Lucy’s hug knocked my ribs out of alignment. The borrowed sweater hung like armor she hadn’t meant to wear. The note on the table might as well have been a confession written in toddler scrawl. Be good. There’s food in the fridge. Good, as if goodness were a task children could perform to earn supervision. Food, as if calories could stand in for care.

We drove to the police station because sometimes you need the floor to be labeled floor by someone wearing a badge. The front desk officer did not hide his disgust well, which felt like solidarity even if policy would have demanded neutrality. He asked the questions his job required. “How long?” “Who else was aware?” “Is the child safe now?” He took the note and made a copy and slid the original back as if it were evidence I would be asked to believe and disbelieve, over and over, depending on the room.

He explained the steps in a voice that sounded like instructions for assembling something you shouldn’t have to own. “A welfare check. Mandatory reporting. CPS will follow up. You may get calls. Tell your daughter’s school there’s an open case, just in case anyone tries to pick her up without authorization.” He paused, and then, softer: “I’m sorry you have to be here.”

Words like welfare and case and follow up have a way of sandblasting the edges off a story until all that’s left is a file. I signed where he told me to sign. I did not cry in the lobby. I have learned over the years that my mother believes tears are a kind of performance; I refuse to give her the satisfaction of thinking she taught me that.

Back at the house, we gathered Lucy’s backpack. Her eleven crayons had become nine because life makes its own math. I found the other two under the couch later, a purple streak on the baseboard like a mood the room had and a black one trapped beneath a chair leg. We left the lights on until we reached the door and then, one by one, I turned them off. It felt like a ceremony the house deserved.

When my mother called a week later, her tone aimed for bewildered wounded. “What did you do?” If you want to measure whether a person is capable of remorse, put that sentence beside the thing they did.

“I filed a police report,” I said. “For abandonment.” The word landed like a plate shattering and kept sounding in the pause.

The shouting that followed did not bother to locate a fact. “You filled her head with lies.” “You’ve always been jealous.” The accusations slid around the truth like oil repelling water. I don’t remember the exact end of the call, only the feeling of heat in my palm, as if the phone had caught fire from the friction of two realities refusing to share a border.

Grandma didn’t deliver comfort so much as clarity. “I changed the trust,” she said. “Because I am tired of outliving the consequences other people set in motion.” She explained—in broad strokes, not legalese—what it means to own a house through a revocable living trust, how a signature in one decade reaches its fingers into another, how structure can be both protection and trap, depending on who’s holding the pen. “I gave away that house once to keep the peace,” she said. “Turns out silence doesn’t keep the peace. It only makes a comfortable place for the wrong story to sit.”

If you are lucky, you get one person in your lineage who is fluent in the language of boundaries. Mine is my grandmother. She writes in declarative sentences that end with periods and begin with I.

The social media storm was, in its own way, a gift. It was public enough to be undeniable and petty enough to be embarrassing for the people who started it. Mom’s post read like a script she’d tested on sympathetic friends: vague nouns, heavy verbs, a fog machine of implication. “Betrayal.” “Manipulation.” “After all we’ve done.” Jenna’s contribution weaponized the word family and hung it like a curtain over the actual room. Travis introduced a hashtag like a prop gavel.

Grandma’s post did not argue. It stated. People forget how powerful a clean sentence can be. “I changed my will and my revocable living trust,” she wrote. “I did it because my daughter and her husband left their six‑year‑old granddaughter alone in the house I own while they went on vacation. I found the child myself that evening. No one tricked me. I’m not confused. I’m angry, and I’m done.” It is difficult to mount a counter‑narrative against a woman telling the truth about her own actions with her own name attached.

Neighbors who owed Grandma favors from the eighties remembered. Former students she used to tutor at the library remembered. People who had borrowed dishes for funeral luncheons and forgotten to return them remembered. The town has a long memory when it wants to.

Two days later, when Jenna arrived with carnations and sunglasses and an apology shaped like a performance, Grandma’s refusal to open the door was not cruelty. It was a lesson plan written for an audience that had always skipped class. She watched through the glass because she had learned that some doors are safest as windows. She waited an hour to throw away the flowers because she knows the half‑life of dramatics.

In the six‑month aftermath, the legal machinery moved at its own pace, as it does, like a river eroding a bank you’ve been standing on for years. My parents, Jenna, and Travis vacated the big house on day thirty. On day thirty‑one, the front lawn looked like any front lawn, which is to say the same as yesterday but honest about the change. They rented a duplex near the highway. This is not an indictment; it is a geography lesson. The map reroutes when the route you chose turns out to be a cliff.

CPS did what CPS does: they checked, documented, circled back, taught classes that cannot fix character but can, sometimes, shore up behavior. The local news ran a polite, factual segment that included the phrase “child endangerment” and the phrase “probation,” and then—because local news is also a bulletin board—it mentioned the mandatory parenting classes. I did not watch the segment live. Someone sent me a clip. I clicked it in a kitchen where the dishwasher hummed and the light over the sink made the stainless look like a lake at noon. When the clip ended, I closed my laptop and stood there long enough for the cycle to switch from wash to rinse.

People ask about Lucy in a tone I recognize from hospital waiting rooms. They want a prognosis. They want to know if the light stayed on. Here is the answer I know how to give: she sleeps with the door cracked now because she likes to hear the house breathing. She still lines her crayons in a row before she begins. She counts, out loud, in a whisper, the way a person might count if they were talking to a bird on the windowsill. At bedtime she asks me to turn off the hall light last. “So the dark doesn’t rush in,” she says. I turn it off standing in the doorway so my body can be the door for a second longer.

On the drives to Grandma’s each week, Lucy narrates the scenery like a reporter in a moving studio. “Horses. Red truck. Cloud that looks like a sandwich.” She has opinions about billboards. She wants to know why the man selling tires looks so happy. “Because he loves tires,” I say, and we both laugh too hard for the joke. We stop at the same diner half the time and at different places the other half because children like both ritual and surprise in doses measured with a coffee spoon.

Grandma waves from the porch before we’re out of the car, the way she did before any of this when I was a kid coming by after school to avoid the silence at home. She has learned how to hold happiness without looking over her shoulder to see who disapproves. That is its own curriculum. She pretends to scowl at our noise and then cranks the radio while we unload snacks like we’re stocking a bunker.

On quiet afternoons with her, I have asked questions I was afraid to ask when I was younger. “Did you know, back then, when you gave them the house, that it would turn out like this?” She shakes her head. “I knew what I was told to know,” she says. “Your mother was convincing when she wanted something. I thought I was giving her a stage. I didn’t realize I was also giving her a microphone she would never put down.”

“What changed?”

“You,” she says, not unkindly. “And Lucy. And me. I stopped believing the story where my job was to keep everyone comfortable in a room where I was never allowed to sit.”

When I stand in front of the big house now—on rare days when grown‑up errands take me past that street—I don’t feel triumph. I feel the kind of quiet you feel in a library where the shelves hold books you’ve already read and survived. The deed has my name. The porch still has the nail hole where a wind chime used to hang. The crack in the living room ceiling is visible if you know where to look. I have imagined tearing it down to the studs and rebuilding with windows that face truth. I have imagined selling it to a family who will fill it with a kind of noise that never once needs to be photographed to be real. I haven’t decided yet. The not deciding is, for once, a luxury instead of a hazard.

My mother still calls sometimes from different numbers, because she likes to pretend she can outrun caller ID. I answer less than I used to. When I do, she tries out new narratives like outfits. In one I am ungrateful. In another I am brainwashed by an elderly tyrant. In a third, everything is my fault because I refused to be flexible about space in a car. I have learned to say, “That’s not what happened,” and then to end the call before the conversation becomes a hall of mirrors.

Jenna’s profile is still locked. Every so often, a screenshot escapes gravity and lands in my messages. It is always an old photo. Recitals and roses and smiles that ache if you look too long. I try not to look too long. I am not immune to nostalgia; I am only careful about its dosage.

Travis once sent an email with the subject line Re: House. The body was an arrangement of words that wanted to be an argument. I wrote back three sentences: “Please direct any legal questions to Grandma’s attorney. I will not discuss this with you. Do not contact me again.” He did not reply. I printed the email anyway and slid it into a folder labeled For the File, because some days paperwork is a boundary you can hold in your hand.

If you are reading this because you are trying to decide whether to pick up the phone and report a thing no one wants to believe, here is the only advice I feel qualified to give: do it. Call the number. Tell the truth to the person whose job it is to hear it. There is a version of the story where you stay quiet and hope the next time is different. There is another version where you do not gamble with a child’s night.

The day CPS closed the case, the social worker—kind eyes, precise questions—said, “You did the right thing.” I did not know where to put the sentence, so I put it on the shelf with the other sentences I reach for when I think maybe I overreacted: She’s six. There wasn’t room in the car. Be good. There’s food in the fridge. I stack the truth on top of the lies so the lies cannot breathe.

Spring will come soon. We are planning a small trip—the kind of vacation that doesn’t endanger anyone, the kind where the best photo is of a half‑eaten sandwich and a sunburned nose. Lucy has packed three books and a bathing suit. Grandma claims she is only bringing sunscreen and crossword puzzles, but last week I found a stash of candy bars in her pantry that says otherwise. My husband has already argued with the rental car website twice and emerged victorious. These are the logistics of a life reclaiming its shape.

On a Tuesday that meant nothing on the calendar, Lucy drew another house in the back seat as we headed toward Grandma’s. This one had a porch swing and a tree for shade and a little figure on the steps. “Is that you?” I asked, catching her eye in the rearview mirror.

She shook her head. “That’s Grandma.”

“And you?”

She lifted the yellow crayon without looking up. “I’m the light,” she said again, but this time she laughed like the idea tickled.

There is no moral at the end of this, only a map. It has three points: a child, a woman who drove without waiting for permission, and another woman who finally stopped mistaking quiet for peace. Draw lines between them. That shape is a home. The rest—the posts, the captions, the neighborhood opinions—can orbit if they want. We don’t live there anymore.

If I ever teach Lucy anything about forgiveness, I hope I teach her that it does not require the return of proximity. You can forgive and still keep the door latched. You can forgive and still say, “You may not take care of me.” You can forgive and still save the note that says Be good, There’s food in the fridge, not as a relic to worship but as a warning label for the story you will not let repeat.

Sometimes, late, when the house is dark in the way we chose, I walk through each room and touch the wall with my fingertips the way you touch a sleeping child’s shoulder to tell your own body the child is safe. I pass Lucy’s door and hear the soft swing of her breath. I pass the table where the purple crayon left a crescent. I pass the window that looks out at a street where nothing dramatic is happening. It is the best kind of unremarkable.

I turn off the last light.

Not for a picture. Not for show. For us.

News

MIL Lost It at My Baby Shower & She Insulted Me, Tried to Name My Baby but Ended Up Getting Arrested After Making a Scene.

Part I – The Announcement When I first saw the faint pink lines appear on that test, I cried —…

On Thanksgiving, My Uncle Blocked The Door And Said, ‘You’re Not Family Anymore — Leave.’ I Saw My Mom Laughing Behind Him, Handing My Seat To My Sister’s Boyfriend. I Just Nodded, Got Back In My Car… And Sent The Message I’d Been Saving For Months. Five Minutes Later, Half The Table Stood Up — And Walked Out.

Part I: The Invisible Son My name’s Oliver, and I’ve spent most of my twenty-eight years learning how to take…

After twelve years of financial support, my parents texted: “You’re not welcome for Christmas. Your sister’s husband needs family space.” I didn’t argue. I simply replied, “Okay.” Then I called my lawyer, opened a spreadsheet, and quietly calculated the total amount I had given them over the years — $520,142.68.

I. The Message After twelve years of financial support, my parents texted: “You’re not welcome for Christmas. Your sister’s husband…

My Parents Left Me At A Train Station As A joke! «Let’s See How She Finds Her Way Home» – I Never Went Back…

I am Megan Miller, 32, a graphic designer in Chicago. This morning, my phone lit up. 29 missed calls from…

My Pilot Sister Saw My Husband on a Business-Class Luxury Flight to Paris with Another Woman

My sister, an airline pilot, called me. “I need to ask you something strange. Your husband—is he home right now?”…

A Mother Worked Collecting Trash, Her Daughter Was Mocked for 12 Years — Then at Graduation, One Sentence Made the Entire Hall Rise in Tears

Part One: The Weight of Whispers Emma Walker learned early that cruelty doesn’t always announce itself with fists or screams….

End of content

No more pages to load