When I was eight, my brother Jackson won the county spelling bee and my parents threw him a party with fifty guests and a cake taller than me. When I won the science fair a month later, they forgot to pick me up from school. I walked home in the rain, clutching a paper trophy that melted into pulp in my hands. That was childhood in a nutshell: Jackson, the miracle child they’d tried a decade for; me, the accident that showed up uninvited.

He got a nursery painted with pastel clouds and a crib that cost more than our car. I slept in a dresser drawer lined with old blankets. His baby teeth lived in a labeled box; mine went down the trash with dinner scraps. I stopped expecting fairness before I learned long division.

By ten, I’d already raised myself. Packed my own lunches. Walked forty minutes to school while Mom drove Jackson the same route in her SUV, waving as she passed. Teachers said I was independent. They didn’t know independence was just the absence of anyone showing up.

Mom liked to tell people she loved us equally. She’d say it at Jackson’s hockey games, the ones she never missed, while I sat on the track field alone at meets she forgot existed. Dad would insist I was imagining things, usually while showing coworkers Jackson’s trophies. In the living room, there was a shrine to him: medals, certificates, smiling photos through every year of his life. I got one school picture on the fridge—second grade, chipped tooth, outdated by almost a decade.

When I was sixteen, I got into an advanced science program. It came with a scholarship to a summer camp at MIT. The kind of thing that could change a life. I came home waving the acceptance letter, shaking with excitement. Mom barely glanced up from the stove. “That’s nice, honey. But Jackson has a tournament that week, and we can’t drive you.” The camp was three hours away. I walked back to my room and folded the letter into a box under my bed with the other proof of things that didn’t matter.

So I started saving. Babysitting, tutoring, whatever I could. I knew they wouldn’t pay for college. Jackson’s fund had been announced like a national achievement—forty thousand dollars, Mom bragged at every family gathering. When relatives asked about me, she’d smile and say, “She’s the bookish one. She’ll get scholarships.” As if intellect were a consolation prize for being unloved.

Then, at seventeen, my body started to betray me. Bruises bloomed without reason. I couldn’t climb stairs without my knees trembling. But complaining was useless in our house; pain just made me inconvenient. I worked double shifts until the day I fainted at the diner. When I woke, there were tubes in my arms and a doctor saying words that didn’t make sense: acute leukemia, advanced, aggressive.

For the first time in my life, my parents looked at me like I mattered. Mom cried—real tears. She held my hand through chemo and brought flowers that made the nurses smile. Dad took time off work, something he’d never done for any of my school events. For three months, I had the parents I’d always imagined. They brought balloons, bought me soft blankets, told me I was strong. Mom said she was proud of me. I cried harder than I did from the chemo.

The treatment worked. My counts improved; the doctors said remission was possible if we kept going. I believed them. I believed her.

Then Jackson got into Columbia.

He hadn’t earned it—his grades were mediocre, but Mom called it destiny. The acceptance letter came with a bill that insurance could never cover. The next day she sat on my hospital bed, smoothing the blanket with that fake softness she used before delivering bad news.

“Sweetie,” she began, “we need to talk about your treatment costs.”

I stared at her, waiting for a punchline.

“The insurance only covers so much,” she said. “With Jackson’s tuition—well, we just can’t do both.”

It took me a second to understand. “You’re saying you’re stopping my chemo?”

Her smile tightened, like she was explaining math to a slow child. “We have to be realistic, darling. Jackson’s education is an investment in the future. Your treatment is…” she hesitated, searching for the least offensive word, “prolonging the inevitable.”

I heard my heartbeat louder than her voice.

“You’ve had a good life,” she said gently. “And we’ll make you comfortable. But Columbia only accepts students once.”

She actually called me selfish—for wanting to live.

When she left, I lay there staring at the IV line, at the slow drip of medicine that was suddenly on a timer. I’d spent seventeen years being the kid they forgot, and now I was something worse: the expense they couldn’t justify.

I waited until the hallway went quiet. Then I grabbed my phone with shaking hands and typed medical emancipation minor into the search bar. My fingers trembled too much to scroll straight, but I kept reading. There were stories—teenagers like me who’d fought for their own treatment when parents refused. Screenshots of court cases, definitions of medical neglect. I saved everything I could find until my eyes burned and the chemo pump beeped a warning.

By sunrise, I had two dozen screenshots and a flicker of something I hadn’t felt in weeks: control.

When Dr. Stone came in for rounds, he froze at the sight of me—awake, alert, and clearly wrecked. “Everything all right at home?” he asked.

The question cracked me open. I told him everything—my mother’s words, the tuition, the decision to stop my care. His face changed as I spoke, soft concern hardening into fury. When I finished, he set his tablet down hard enough to make it rattle.

“You’re not being discharged,” he said. “Not until we figure this out.”

He paged the social worker before I could even breathe. Then he sat beside my bed and explained what would happen if chemo stopped now. The leukemia was responding; my counts were climbing. Quit halfway through and the disease would come roaring back—stronger, faster, lethal. “This isn’t prolonging the inevitable,” he said. “This is saving your life. Ending treatment now would kill you.”

Hearing it in his voice—flat, factual, angry—made the truth undeniable: my parents weren’t just neglecting me anymore. They were trying, politely and rationally, to let me die.

The social worker’s name was Judith Green. She came into my room less than an hour after Dr. Stone paged her — a woman in her forties with tired eyes and the calm of someone who’d seen everything and stopped being shocked by most of it. She set her notebook on her lap, pulled a chair close to my bed, and said, “Start from the beginning.”

So I did. I told her about the spelling-bee party with the three-tier cake, about the science-fair trophy I carried home in the rain, about the MIT camp I never got to attend. She wrote while I talked, nodding, never interrupting. For the first time in my life, an adult listened without trying to explain my parents’ behavior away.

When I finished, she read over her notes and said quietly, “What they’re doing is called medical neglect. It’s when guardians make a decision that endangers a child’s life.”

I stared at her. “You mean illegal.”

“Sometimes criminal,” she said. “But we’ll start with legal.”

Judith called the hospital’s ethics committee and began collecting evidence: every lab report, every note from Dr. Stone, every line in my chart that proved the treatment was working. She promised to move fast — days, not weeks — because every skipped chemo cycle was another chance for the cancer to come back.

That night I texted Jackson. Come alone. I need to talk.

He didn’t reply for hours. I imagined him at dinner while Mom explained why it was better for me to die quietly than for him to take out loans. At seven o’clock he finally wrote back: I’ll come after work.

Dr. Stone stopped by again before his shift ended. He handed Judith a folder full of typed pages on hospital letterhead — my prognosis, survival percentages, the math of what life was worth. “With continued treatment,” he said, “seventy percent of patients survive five years. Without it — less than twenty.”

I looked at the numbers until they blurred. My mother had decided that fifty percentage points of hope were too expensive.

A young guy from billing came next, clutching a tablet and sweating through his shirt. He explained that my chemo so far had cost around $40 000, most covered by insurance. The out-of-pocket remainder? Ten thousand dollars. Ten thousand to finish the protocol, ten thousand between me and a grave. Mom wasn’t sacrificing her fortune. She was saving my brother’s meal plan.

When Jackson finally arrived, he looked like he hadn’t slept in a week. His work apron still smelled faintly of detergent. He sat in the chair by my bed, staring at his shoes.

“I told Mom I’d take out loans,” he said quickly. “She said no. Said it would ruin my credit.”

“So you’re letting me die to protect your credit score?” I asked.

He flinched. “You don’t understand — she said —”

“I understand perfectly.”

He started to cry, whispering about how Mom controlled everything — his classes, his friends, even his thoughts. He said he knew what they were doing was wrong but he didn’t know how to stop her. I wanted to feel sorry for him, but I was too tired to hold his guilt for him.

Judith appeared in the doorway then, a quiet storm in sensible shoes. She asked Jackson if he’d be willing to write a statement about what he’d seen growing up — the favoritism, the neglect, all of it. He hesitated, then nodded, wiping his face with the sleeve of his uniform. She handed him a clipboard. “Be specific,” she said.

After he left, Judith looked at me. “Tomorrow we file for emergency court authorization. You’ll have the hospital on your side.”

That night Mom called. I didn’t answer, but I listened to her voicemail. Her voice was tight, trembling with practiced outrage.

“You’re being selfish, Claire,” she said — she only called me by my full name when she wanted to sound righteous. “You’re destroying this family. You’ve always been jealous of your brother. Stop making us look bad.”

I deleted it before she could finish and turned off the ringer.

Sleep didn’t come. I dreamed of drowning while people watched from the shore.

In the morning Judith showed up with coffee and a man in a wrinkled suit. “This is Yousef Saxton,” she said. “Legal Aid. He’s taking your case.”

He shook my hand and sat down with a yellow pad. His handwriting was neat and patient. After twenty minutes of notes, he looked up and said, “We’re filing for temporary medical authority to transfer decision-making from your parents to the hospital. It’ll be fast. Life-or-death cases usually are.”

The ethics committee scheduled their review for the next day. A woman named Laya Hansen came to interview me first, silver hair and kind eyes that saw too much. She asked if I understood my illness, the treatment, the risks.

“I’ve been making my own choices since I was ten,” I said. “This one just decides if I get to keep making them.”

That afternoon my parents arrived with a lawyer. I heard them before I saw them — Mom’s high-pitched outrage, Dad’s heavy silence, the lawyer’s oily baritone about “parental rights.” Judith met them in the hall, her voice calm but firm. I heard the word neglect more than once. Then the door shut, muffling everything.

Nurse Sandra checked my IV afterward. She looked at me for a long time before speaking. “I’ve seen this before,” she said quietly. “Parents who can’t handle the fear or the bills. They tell themselves giving up is mercy. But it’s not your job to make dying easier for them.”

Her words sank in deeper than anything else had.

At six o’clock Jackson texted me a photo of three pages of handwriting—his statement. Every forgotten birthday, every missed event, every time they’d chosen him. At the bottom he’d written, I’m ashamed I never stood up for her. I will now.

I saved the picture to my phone and stared at it until my eyes burned.

That night, instead of sleeping, I opened a new note and began to write everything I could remember: the trophies, the missed rides, the lunches, the quiet rooms. Seventeen years of evidence, finally in my own words.

By dawn I had five pages—my life reduced to bullet points of proof.

The ethics committee met that afternoon. By evening, Judith came back to my room, hair pulled loose from its bun, smiling like someone who’d just won a small war.

“They voted unanimously,” she said. “The hospital’s petition for emergency authority is going forward. You’re getting your chemo.”

I should have felt triumphant. Instead, I felt hollow—like relief and grief had fused into the same ache.

“They’re going to hate me,” I whispered.

“They already do,” Judith said softly. “That’s not on you.”

Two days later, we were in court.

The hearing room wasn’t dramatic—no jury box, no gavel slam, just a small desk, fluorescent lights, and a woman judge with tired eyes. I sat beside Yousef, trying to look brave while my parents sat across the aisle with their lawyer. Mom wouldn’t meet my gaze. Dad looked like he wanted to disappear.

Dr. Stone testified first. He talked about remission percentages and blood counts, showed charts that even a stranger could understand. Seventy percent survival with treatment. Less than twenty without. The numbers filled the room like ghosts.

Judith went next, stacking folders on the table like evidence in a trial about love gone wrong. She read from Jackson’s handwritten statement—every forgotten birthday, every missed pickup, every time they’d chosen him. She read from my five pages too, the notes I’d written when I couldn’t sleep. Seventeen years of neglect compressed into facts that couldn’t be dismissed as teenage exaggeration.

Their lawyer tried to make it sound like the hospital wanted profit, like I’d been manipulated into fighting for chemo I didn’t need. But Yousef was ready. He stood up and asked one quiet question that cut through the noise.

“If this was about love,” he said, “why did it end the day Columbia sent an acceptance letter?”

No one had an answer.

Then the judge asked me to testify. My knees shook as I walked forward. “What do you want, Claire?” she asked, using the name on the hospital file.

“I want to live,” I said. “That’s it. I understand my parents can’t pay, but there are other ways. Payment plans, aid, anything. Stopping treatment will kill me. I’m not ready to die.”

The room went still.

The judge turned to my parents. “Did you explore any financial assistance before deciding to stop treatment?”

Dad admitted they hadn’t. Mom started crying, claiming she only wanted me comfortable, that chemo was torture. The judge leaned forward. “Are you choosing your son’s tuition over your daughter’s life?”

Mom’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. The silence said everything.

The judge ruled on the spot. The hospital was granted temporary authority to continue my treatment. She ordered my parents to cooperate with Medicaid and charity applications, to sign whatever forms were needed. Her final words echoed in my head long after we left the courtroom: ‘A child’s right to live outweighs a parent’s right to give up.’

Outside, the air smelled like rain. Mom tried to reach for me, but Yousef stepped between us. Dad just looked at the ground. Jackson wasn’t there.

Back at the hospital, Judith met me with more paperwork—Medicaid applications, charity forms. My hand cramped signing my name so many times. Each signature felt like reclaiming a piece of myself.

When Dr. Stone stopped by, he told me he’d scheduled my next chemo cycle. “Your counts are still strong,” he said. “If we stay the course, you’ll finish around graduation.”

Graduation. A word that suddenly meant future.

That night, Jackson came. He’d deferred Columbia, he said. Planned to work, save, maybe attend state school. “I couldn’t go,” he admitted. “Not knowing what it cost.”

I wanted to tell him he didn’t have to prove anything, but maybe he needed to. So I nodded.

The next morning, Mallerie—my coworker from the diner—walked in carrying snacks, a phone charger, and a card signed by everyone from work. They’d raised three hundred dollars. I cried harder than I had in court. People who barely knew me cared enough to fight for my life when my parents didn’t.

Three days later, Yousef called. “The judge signed the full order. You’re legally emancipated for medical decisions until you turn eighteen.”

For the first time, my life belonged to me.

The months that followed were the hardest and the best. Chemo was still hell — nausea, exhaustion, the mirror showing a stranger with no hair and pale skin — but I could breathe again. Not because my lungs were clear, but because nobody could take the medicine away. Every needle prick, every ache was mine now. My choice. My fight.

Judith found me a spot in a transitional housing program for medically fragile teens. It wasn’t glamorous — one bedroom, scuffed floors, secondhand furniture — but it was mine. I moved in on a Saturday while my parents were out of town. Jackson helped me pack what little I owned. Clothes, a few books, the science fair trophy I’d carried home in the rain years ago. When we finished, he hugged me for the first time since we were kids. “I’m sorry,” he said.

“You don’t need to be,” I told him. “We both survived the same house.”

My treatment ended three weeks before graduation. Dr. Stone said the words “full remission,” and I cried right there in the exam room. He printed my latest labs and handed them to me like a diploma. “You did this,” he said. “You fought for it.”

Graduation was held in the high school gym. I wore the cap over my bald head and walked across the stage to polite applause from strangers. Mom and Dad didn’t come; they weren’t invited. Jackson sat in the back row, clapping until his palms turned red. When the principal handed me the diploma, I realized I wasn’t just finishing high school — I was finishing seventeen years of invisibility.

Life after chemo was quieter. I worked part-time doing data entry for a medical records company. Mallerie helped me set it up — she’d made me a calendar of coworkers who volunteered to drive me to appointments. People who owed me nothing gave me everything my parents never did: community.

I started seeing a therapist the hospital recommended. At first I told her I didn’t want to talk about my family. She smiled and said, “That’s fine. We’ll start with you.” And slowly, I did — the nights alone, the birthdays forgotten, the hospital bed where I learned that love could be conditional. She didn’t tell me to forgive them. She said forgiveness was optional; peace wasn’t.

Jackson started school at the state university that fall. He came by my apartment one weekend, nervous but proud. “I think I’m finally doing something for me,” he said. He was different now — still quiet, but lighter. We sat on the floor eating cheap takeout, laughing about how weird it felt to be normal siblings after everything.

My parents sent a letter months later through their lawyer — supervised visitation requests, apologies written like business memos. I read it once, then folded it away. I wasn’t ready. Maybe I never would be.

One evening, after my shift, I rearranged the small bookshelf in my apartment. On the top shelf I placed three things: my science fair trophy, the acceptance letter to the MIT camp I never got to attend, and the court document granting my emancipation. Three pieces of proof that I’d been worth fighting for all along.

I stood back and looked at them — not as reminders of pain, but as monuments to survival. The girl who used to walk home in the rain now had her own key, her own roof, her own heartbeat unowned by anyone else.

Sometimes, I’d still wake up from nightmares — Mom’s voice telling me to “be realistic,” Dad’s silence like a closed door — but the fear faded faster now. When I needed grounding, I’d whisper the simplest truth aloud: “I lived.”

The last time I saw Dr. Stone, he hugged me before I left. “You’re going to do great things,” he said.

“I already did one,” I told him. “I stayed alive.”

Outside, the air smelled like spring. The city buzzed around me — strangers rushing home, streetlights flickering on. For once, I didn’t feel small in it. I felt infinite.

Because surviving isn’t about miracles. It’s about refusing to die on someone else’s timeline. It’s about deciding your life is worth saving — even if you have to be the one to save it.

News

I won $333 million in the lottery. After years of being treated like a burden, i tested my family called saying i needed money for meds. My son just blocked me. My daughter just said figure it out, not sick. But my 20-year-old sick son drove 400 miles with his last $500

I won $333 million in the lottery. After years of being treated like a burden, I tested my family by…

When I Learned My Parents Gave The Family Business To My Sister, I Stopped Working 80-Hour Weeks For

When I learned my parents gave the family business to my sister, I stopped working 80our weeks for free. Dad…

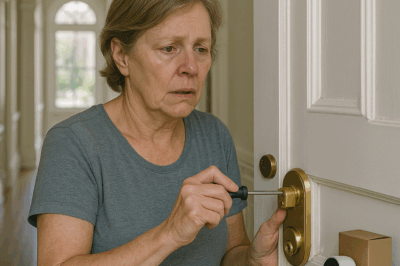

I bought a mansion in secret. Then one afternoon, I caught my daughter-in-law giving her family a grand tour. “The master suite is mine,” she declared proudly. “And my mom can take the room next door.” I stood in silence, hidden in the hallway, listening to every word. I waited until they finally left. Then I changed every single lock, one by one. And I installed security cameras. What those cameras captured later… left me speechless.

“I waited for them to leave, changed every lock, and installed security cameras. If you’re watching this, subscribe and let…

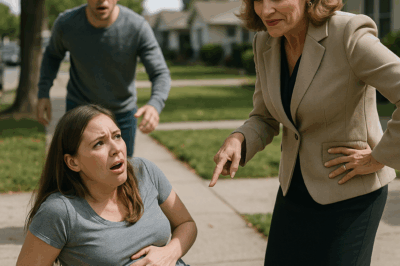

HOA Karen Tripped My Pregnant Cousin on the Sidewalk — 10 Minutes Later, SEALs Surrounded Her

Can you believe it? This woman just intentionally tripped a five-month pregnant woman on a public sidewalk and actually smiled…

My Parents Gave My Room To My Brother Because He Needed More Space. They Laughed, Expecting Me To Sleep On The Floor. But I Said I Would Be Moving Into The New House I Just Bought And They Went Silent…

Part 1 — The Dinner I should have known something was off the second I heard my mother’s voice on…

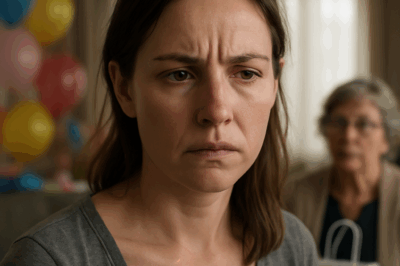

At My Daughter’s Birthday Party, My Mom Tried To Take Her College Fund To “Help” My Sister Pay Her Debts. So I Announced I Had Closed The Account Last Month, And Her Reaction Ended Everything…

I grew up believing that money was love. My mother, Patricia, taught me that without ever saying it outright.Every allowance…

End of content

No more pages to load