Part One: Maple Street, Boston

Winter comes early to Boston, walking in on people without knocking. By the first week of November, the wind already had opinions, and the first powdery snow had dusted the brownstones into postcards. Inside the little café on Maple Street, the espresso machine breathed out steam like a gentle dragon, and the bell over the door chimed with the optimism of people who forgot their gloves.

Eleanor Griffin wiped a clear swath into the window fog and checked the time. The glass still held the imprint of her palm after she pulled away, a soft oval that looked like a promise and felt like a map. “Another ten minutes,” she told herself, though she’d meant to leave five.

“Eleanor, you can finish up,” called Janet from behind the pastry case. The owner wore kindness the way other people wear perfume—you noticed it across the room. “Noah will be getting out of school. Go on.”

“Thanks, Janet.” Eleanor untied her apron and folded it neatly, the way she folded everything in her life that could be made orderly by hands. There were only a few such things, but she was a champion at them.

Seven years alone had taught her the choreography of two-person days: the quick dinners, the backpack checks, the math worksheets with smudged pencil ghosts. Noah’s father, David, had disappeared from the world the way headlights vanish around a curve—here, then gone—six months after Noah was born. Grief had moved in with Eleanor like a long-term tenant; she’d made room for it in the linen closet and insisted it at least put away its dishes. Somewhere in those early years she’d learned how to laugh again, and how not to apologize for laughing. She’d learned that love could happen anyway.

Outside, the snow fell with that New England confidence—like it knew what it was about and didn’t need your permission. Eleanor tucked her scarf close and walked the two blocks to their apartment over the bakery that always smelled like raisin toast even on days it was closed. She stopped at the cluster of mailboxes in the entry and thumbed through the usual paper—circulars, a bill, a coupon for HVAC services that assumed a certain square footage she did not possess—and then paused at an envelope that knew it was elegant. Cream paper, gold ink, just the right weight.

She opened it with a fingernail because why keep secrets from yourself. Inside, script performed itself across the page: You and Noah Griffin are cordially invited to the wedding of Victoria Griffin and Richard Hamilton. The Regent Plaza Hotel. Black tie. RSVP requested. The gold letters were so proud of themselves you could hear them preen.

“Oh,” she said to the empty stairwell.

Victoria—beautiful, social, polished to a high gloss—was marrying into a family whose last name introduced itself in real estate sections and gala programs. Eleanor’s first thought was not jealousy. It was the memory of her father, William, in his navy suit that smelled like cedar and starch, saying, You do what’s right because it’s right, kiddo. People figure out the rest eventually. He had been gone three years now, a heart attack drawing the curtain mid-scene, and since then the family landscape had shifted like ice floes. Her mother, Martha, had leaned into the Hamilton orbit with the avidity of someone who had read the brochure and wanted the timeshare.

Upstairs, Noah’s shoes were by the door like punctuation. He looked up from the kitchen table when she came in, pencils asleep next to his math test. “Mom!” He launched himself at her. He was all elbows and poetry and those solemn eyes that had belonged to his father, but his smile was all his own invention.

“How was today?” she asked, thrilled to be the person who got to.

He produced the math test with a flourish. “A hundred,” he said, as if confessing. “We did fractions and Ms. Alvarez said I have a good way of seeing things.”

“You do,” Eleanor said, because how else do you answer the truth.

Later, as she slid chicken into the oven and pretended the invitation wasn’t peering over her shoulder, Noah found it where she’d set it on the counter. “Aunt Victoria’s getting married?” His voice was carbonated with wonder. “Can we go? Please?” He had never seen a hotel ballroom. He had never stood under a chandelier that looked like the Milky Way had decided to visit.

Eleanor’s first instinct was no—too complicated, too performative, too much of everything—but the way he said please rearranged her day. “We’ll go,” she said, and felt at once brave and foolish, which is often the correct ratio for parenting.

That night, after Noah fell asleep in a tangle of superhero sheets, Eleanor took down the old photo album. The leather had softened with years and handling. There was William at a company picnic, sleeves rolled, laughing with his whole face. There was Eleanor at twenty-three, squinting into the sun as if daring it to blink first. There was a family that had once felt like an uncomplicated noun. She pressed her hand over the picture of her father and said, “I’ll go, Dad.” It felt like practice for a harder sentence she would have to say later.

In the morning, she called Victoria. “We’ll be there,” she said.

“Oh,” Victoria said, surprise like a fingernail behind the word. “How nice. Mother will be… pleased.” The pause before pleased did heavy lifting. Then, as if reciting from a handbook, “Do make sure you and Noah have proper attire. Richard’s family are all high society people.”

We wouldn’t want to embarrass you, Eleanor didn’t say. Out loud she said, “We’ll be presentable,” and after she hung up, she wrapped her coat around herself and went to work.

A week later, Boston performed for the wedding as if the city had received a script. The Regent Plaza Hotel, all marble and echo, shone as if someone had polished the air. White roses gazed down from every ledge; gold ribbons behaved like they had gone to finishing school. Eleanor and Noah stepped out of a taxi and into a lobby that smelled like expensive soap and confidence.

Noah tugged at the sleeve of his small suit, the one she’d bought with savings and hope. “Mom,” he whispered, “everyone is so… sparkly.”

“They are,” she agreed. “We belong here, too.” She squeezed his shoulder, because truth sometimes needs muscle memory.

They were guided—politely, apologetically—to seats near the back of the ceremony hall, a place where you could still see the vows if you leaned a little. Victoria glided in pure white, hair like a commercial for hair, eyes bright with the knowledge of cameras. Richard Hamilton looked solid and pleased, a man to whom good things arrive on schedule. The vows promised what vows always promise, and for a moment Eleanor let herself be lulled by ritual. Love was a language she spoke fluently, though her accent had changed over the years.

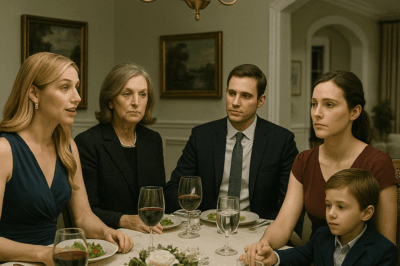

When the reception opened on the hotel’s top floor, it was as if someone had hired a sunset to come inside. Chandeliers held galaxies. Champagne did what champagne does—made strangers temporary co-conspirators. A card on Eleanor’s table read Griffin Family — Relatives, and the table was tucked to the edge like a polite afterthought. Martha was at the head table in a dress that had practiced being flattering and a face that had practiced sophistication. When she looked toward Eleanor, she looked away quickly, as if glances were currency and she had to budget.

The food arrived, beautiful and engineered. Noah took tiny bites like a scientist, eyes wide, cataloging tastes he’d only read about. Eleanor let herself enjoy his enjoyment. Joy is contagious if you let it be.

Then the master of ceremonies tapped the microphone, and the room shimmered down to a hush. “A special entertainment,” he announced. Music floated. The lights softened. A spotlight—showy, white—opened like an eye and settled, to Eleanor’s surprise, on their small table. Every face turned. Noah’s hand found hers under the linen, his palm hot and nervous.

Victoria moved toward them from the stage, her dress a comet tail. She smiled the smile that had bought her a thousand easy entrances. “Everyone,” she trilled, “thank you for sharing my special day. And now—I have another special thing to share.” She gestured, and the spotlight brightened. “This is my sister, Eleanor, and her son, Noah. They live in a somewhat different world from ours.”

Titters. The kind of laughter people make when they don’t want to miss the joke.

Eleanor’s mouth went dry. The old muscle remembered humiliation, but the new muscle tried to hold the line.

“So tonight,” Victoria announced, voice syrupy, “let’s do a little charity auction. This single mother and her poor son—as a set.” She cocked her head. “Would anyone like to buy them?”

Laughter again, freer now, because cruelty sounds like wit if you rent the right ballroom. Noah’s fingers dug crescents into Eleanor’s hand. In that instant she saw herself from the ceiling: a small table, a cheap suit, a navy dress that had cost more than she should have spent, a woman who had learned to swallow. Something inside her sat up.

Martha stood—composure tight as a corset—and plucked the microphone from her younger daughter with the entitlement of an heirloom. “Let me add something,” she said, breathy. “We can start the bidding at zero.” She laughed, delighted with her own improvisation. “I don’t think they have any value.”

The laughter rolled, buoyant now, wicked and relieved.

Eleanor stood, the chair scraping a small protest against the parquet. “We’re leaving,” she told Noah, and the steadiness in her voice surprised them both. But before they could make three steps toward the door, a new voice cut through the room—not loud, exactly, but the kind of quiet you lean toward without meaning to.

“One million dollars.”

Silence doesn’t fall, not really. It settles. It decided to settle then, thick and curious. Heads turned the way sunflowers do.

A man stood near the back of the ballroom, tall, gray at the temples in that way that suggests both time and attention. His suit fit him the way sentences fit people who tell the truth. Blue eyes, watchful. He took a few unhurried steps forward. “I’ll buy this lady and her son for one million dollars,” he repeated, as if confirming a line item.

A nervous laugh escaped someone near the bar. Victoria tried to steer the moment with the skill of a driver who has mistaken the brake for the gas. “Well,” she said brightly, “someone with a sense of humor—”

“This is not a joke.” The man’s voice was soft but edged. He walked to the center of the room as if it had been waiting for him. “James Morrison,” he said, turning so the room could hear and could not pretend later that they hadn’t. “Attorney to the late William Griffin.”

The name moved through Eleanor like memory. Her father’s lawyer. Not the firm Martha was always mentioning at brunch, all hyphen and prestige. The other name. The private one. She had heard it, once, in a conversation that had seemed unimportant at the time.

James inclined his head toward Eleanor and Noah, and the corners of his mouth lifted into a smile that was not for the crowd. He turned to Victoria and Martha, and whatever warmth had been in his face cooled. “Shall we continue this auction,” he asked, pleasant as a receptionist and hard as a verdict, “or shall we move on to the part where we tell the truth?”

You could hear the chandeliers hum. Richard Hamilton looked at his bride with that particular combination of confusion and dread that visits only on wedding days and depositions. His parents leaned into each other, whispering math.

James lifted a hand slightly—as if hushing a classroom—and faced Eleanor again. “Before I speak, I owe you an apology,” he said to her, and the room swayed at the audacity of a man apologizing in a tuxedo farm. “Ms. Griffin. Noah. I am sorry to do this here. But this is where Mr. Griffin asked that it be done.”

“Stop this nonsense,” Martha snapped, her voice higher than she intended. “Who are you? My husband’s lawyers were Carter and Smith. Everyone knows that.”

James reached into his jacket, movement unhurried, and produced an envelope that had been waiting ten years to be opened. “That’s correct,” he said amiably. “For corporate matters. But for personal matters—especially his true will—Mr. Griffin retained me.”

“That’s a lie,” Victoria said, the way some people say cheers. “The will has already been executed. Everything was legal.”

James opened the envelope. A notary seal winked from the paper like a coin. “Yes,” he said. “The apparent will was executed. This”—he lifted the document so the nearest table could read without squinting—“is his final will and testament, dated April fifteenth, two thousand nineteen.”

A technician somewhere, thrilled to participate in story, switched the ballroom’s giant screen from floral montage to legal document. The letters were not fancy. They did not need to be. I bequeath eighty-five percent of all assets, including all shares of Griffin Real Estate and personal property, to be divided equally between my daughter, Eleanor Griffin, and my grandson, Noah Griffin. The room made a sound, not quite a gasp, not quite a cough. The sound of furniture suddenly being worth less than you’d planned.

Eleanor stared at the words until they became shapes. Her father’s voice arrived in her throat and stubbornly refused to speak.

James continued, as if he were narrating a particularly patient documentary. “The remaining fifteen percent is designated as living security for Martha Griffin—no management rights, no further claims. Management of Griffin Real Estate transfers entirely to Eleanor.” He produced a second packet. “These are records of asset flows over the last three years.” The screen obediently changed to arches of numbers and arrows that even laymen could tell pointed in the wrong direction. “They include evidence of illegal transfers executed by Martha and Victoria. Mr. Griffin anticipated—accurately—what would be attempted in his absence.”

Martha rallied. “This is fraud,” she said, and the word sounded odd in her mouth, as if she had borrowed it from someone less decorative. “You can’t just—”

“A judge is present,” James said mildly, nodding toward a severe man near the back who had been pretending to sample the shrimp. The man inclined his head once. People near him shuffled away as if proximity were contagious.

Victoria’s face had gone from bridal blush to paper. Richard’s father stood, outrage pressed as crisply as his shirt. “What is this? We were about to welcome a family of—” He sputtered, a man unused to needing nouns.

James opened one last envelope with the care of a person who knows the weight of what comes next. “There’s a letter,” he said. “From William to Eleanor and Noah.”

He read. And as he did, the grand ballroom—built to amplify celebration—became a chapel. Dear Eleanor and Noah… I’m sorry for keeping this from you… I wanted to protect you… I wanted to expose the truth… You are my successor… kindness matters in business, too… Trust James… I am always proud of you… Grandpa is watching. The words were simple in the way truths are when you stop sanding them.

By the time James finished, Eleanor’s cheeks were wet. Noah, bravely serious, whispered, “Mom, did Grandpa remember me?” She crouched and folded him into her, smelling his hair like an antidote. “Always,” she said. “He always did.” She stood up taller than she remembered how to be.

The room rearranged itself around the new fact of her. Victoria looked very small. Martha looked very old. Richard looked like a man doing math and not liking the answer.

James stepped to Eleanor’s side without touching her, a gentleman at the curb offering a hand to a lady who doesn’t need it but deserves to have it offered. “Ms. Griffin,” he said quietly, “Noah. Let’s go. There’s more to tell you, but not here.”

Eleanor looked once—only once—toward the head table. Then she took her son’s hand, nodded to James, and walked out of the Regent Plaza through a back corridor that smelled like linen and soap. The chandelier light fell behind her like a curtain after the last line is delivered.

In the service driveway, snow came down fat and soft. A dark sedan waited with the kind of readiness that looks like patience. James opened the back door, and Noah climbed in, already asleep standing up. Eleanor slid into the front, held together by bone and will and a father’s voice recited in a stranger’s mouth.

They drove. The city threw its lights against the windshield and watched them slide by. “You must be exhausted,” James said at last, the understatement gentle as wool. “I’ve booked a hotel for tonight. Tomorrow we start the legal work in earnest.”

“Why didn’t he tell me?” Eleanor asked, the question small and enormous.

“He wanted to protect you,” James said, eyes on the road. “He knew what they would do, and he needed to see it done fully. He believed in you, Eleanor. He said—often—that you were the strongest person he knew, and the kindest. He trusted that you’d stand on your own. He trusted me to make sure you weren’t standing alone.”

Outside, Boston kept snowing as if it had a quota. Inside, a woman who had been humiliated in a room full of chandeliers exhaled and began, without fanfare, to become the person her father already knew her to be.

Part Two: The Will and the Way

The hotel room was too nice for sleep. It had the kind of sheets that make you consider a life of crime and the kind of carpeting that forgives all sins. Eleanor tucked Noah in, set his tiny suit jacket over the back of an oversized chair, and stood at the window with a glass of water like it might have answers at the bottom.

Boston glittered under fresh snow. Tail lights stitched a red seam down Boylston; somewhere a plow muttered its old song. A few floors below, the Regent Plaza’s ballroom continued its performance without its unwilling understudy. Eleanor tried to picture the room when the music started up again, laughter resuming, the guests outing themselves as people who preferred the familiar script. She failed. The only thing she could see clearly was her father’s name on the screen, blocky and certain, and the letter James had read in a voice that hadn’t wavered.

She pressed her palm to the glass the way she had at the café window. “Dad,” she said softly, “what have you done?”

“Something loud,” said a voice from the doorway.

James Morrison leaned against the jamb with the posture of a man comfortable at thresholds. He’d changed out of his tuxedo jacket into a dark sweater, and it made him look less like an attorney and more like a person who might help you carry a couch. He nodded at the empty chair by the desk. “May I?”

Eleanor shrugged. “It’s a free country,” she said, and then, because the line deserved better, added, “Tonight, anyway.”

He sat. The quiet in the room was different with someone else in it—less brittle, more companionable. “William asked me to give you space for the big feelings,” James said. “But not the logistics. He said you’d try to pack those in a backpack and carry them up three flights of stairs alone.”

“That sounds like him.” She turned from the window. “Tomorrow?”

“Court at ten,” he said. “Judge Feldman—the gentleman from the back of the ballroom—will sign the temporary orders on the record. We’ll file the asset freezes before lunch, transfer control of the corporate accounts by early afternoon. I’ve already notified the bank’s counsel; they’ll cooperate. HR will be briefed. The board will meet at five. I’d like you to speak to them.”

Eleanor almost laughed. “To the board. Tomorrow. After finding out I apparently own them.”

“You don’t own them,” James said mildly. “You lead them. Different verbs, better noun.”

She sat on the edge of the bed, the mattress a cloud compromising with gravity. “I poured coffee this morning,” she said, and the sentence felt like the truest thing in the room. “I wiped steam off a window.”

“Then you already know how to manage condensation,” he said. “Real estate is eighty percent weather and twenty percent people pretending it isn’t.”

She smiled despite herself. “You’re funny for a man who ruins parties.”

“That’s on my card,” he said, and then waited until the smile had done its work. “You can do this, Eleanor. Your father did not base his life’s work on a hunch. He knew what you could hold.”

“Knowing and holding are different,” she said. “Ask anyone who’s carried a sleeping child up the stairs.”

“I have,” James said softly, and there was something in his tone that suggested a hallway and a lamp left on, but Eleanor didn’t ask. The day had already spilled more secrets than polite company allows.

He stood. “Sleep,” he said. “Tomorrow we move the furniture.”

At nine-forty-five the next morning, Eleanor walked into the courthouse carrying a purse, a folder of documents she didn’t strictly need to carry, and the sort of composure you can only buy with a bad night and a hot shower. James met her in the marble lobby and handed her a coffee the size of an apology.

“Judge Feldman will ask you a few questions,” he said as they moved through security. “Answer like you do at the café when someone asks if the blueberry muffins are fresh.”

“They are.”

“Exactly,” he said. “You don’t oversell. You tell the truth with a little butter.”

The hearing was brief but ceremonial in the way civic moments can be when everyone has decided to act like the system works. Judge Feldman, robed and brisk, reviewed the documents with the economy of a man who reads quickly and remembers everything. He looked at Eleanor over the rims of his glasses.

“Ms. Griffin,” he said, “I’m sorry your introduction to this was… theatrical. I have reviewed Mr. Morrison’s filings and the will. You are prepared to assume control of Griffin Real Estate?”

Prepared was generous. Willing was accurate. But the judge had asked the question like a person offering a hand across a stream. Eleanor took it. “Yes, Your Honor.”

“Very well.” He signed the orders with a pen that had probably done graduations and divorces. “Ms. Griffin, I knew your father. He was a stubborn man. This”—he tapped the paper—“is the most endearing act of stubbornness I’ve seen from him. Mind the city. It’s more fragile than it pretends.”

“I will,” she said, and meant it.

By lunch, the asset freezes were filed and acknowledged. A very competent woman at the bank named Flora switched the authorization on the accounts with the calm of someone moving a decimal place in her sleep. HR sent an all-staff email that said more by what it didn’t say. And Eleanor, who had once considered a triumphant day to be one where the espresso machine didn’t choke mid-rush, stood in the elevator at Griffin Real Estate and watched the floor numbers climb toward a life she hadn’t ordered and couldn’t return.

The doors opened onto a lobby that smelled faintly of walnut and ambition. An assistant with a sharp bob and a sharper schedule stood. “Ms. Griffin,” she said, not quite smiling, not quite not. “I’m Dina. We’ve prepared the conference room.”

“Hello, Dina,” Eleanor said, the way you say nice to meet you to a bouncer. She followed, her heels sounding authoritative by accident.

The conference room was glass on three sides and oak on the fourth. The board members were already there, arranged by age and power like an orchestra. There were the veterans—men who had started with William in the days when you could still buy a triple-decker for less than a car—and the newer faces with their graduate degrees and their impatience.

At the end of the table, an empty chair: William’s chair, still slightly off-center as if he had stood up quickly and meant to return. Eleanor’s breath hitched.

James took the seat to her left, legal pad open, pen at the ready for theater as much as notes. He gave her a look that translated roughly to: You already know how to do this. Talk to people like they’re people.

Eleanor stood. The room adjusted itself around her the way rooms do around new facts.

“Good afternoon,” she said. “You’re probably expecting a speech that explains what happened last night. You’re not getting it. You’ll get the legal summary from Mr. Morrison, and you’ll have copies for your files. What you’re getting from me is a promise and a plan.”

A murmur—respectful, skeptical, hungry.

“My father built this company on two simple ideas,” she continued. “That buildings are places for lives, not just assets. And that you can make money without making enemies of the neighborhoods you build in. If you disagree, you are going to miss William Griffin, because I intend to over-enforce both.”

That earned a soft huff from one of the veterans—a sound the industry makes when it hears itself remembered.

“We will audit the last three years, yes,” she said. “We will return what’s not ours, yes. But we will also look forward. We are going to invest in green retrofits for our older properties—not because it’s fashionable, but because Boston’s winters are expensive and our tenants aren’t ATMs. We will pilot a rent-to-own program in two of our mid-size buildings for working families who have been paying mortgages to landlords for ten years. And we will dedicate five percent of net profits to the William Griffin Foundation to support single parents with housing stipends. If anyone would like to calculate the PR value of that, feel free. I will be in the units talking to the people.”

Silence. Then the veteran—Frank Santos, if her father’s stories were to be trusted—cleared his throat. “Bill used to say, ‘If you can’t explain it to the woman pouring your coffee, it’s a bad deal.’”

Eleanor smiled. “I pour a mean coffee. You can explain everything to me.”

Laughter—real, not polite. A younger board member in a navy suit shifted forward. “With respect, Ms. Griffin, that’s a lot of change.”

“With respect,” she said, “it’s less change than the climate is planning without our permission.”

Even James blinked. Dina, in the doorway, let her mouth curl up the smallest amount.

They voted to support the audits and the pilot programs. They asked questions about tax implications and tenant vetting and supplier contracts. Eleanor answered what she knew, said I’ll get back to you where she didn’t, and never once tried to make up a number. By the end of the hour, the air in the room had learned a new shape.

After, in William’s office, she stood at the window that made the city look like a map you could write on. His photo sat on the credenza, yellowed slightly at the edges from being near sunlight and loyalty.

“You made that look easy,” James said, rolling his pen between his fingers.

“It was not,” she said, soft. “But it was right.”

He nodded. “How’s Noah?”

“At school,” she said, and felt the wire in her chest tighten the way it always did when the day stretched far and he was not in it. “He asked for pancakes for dinner.”

“Then that is our next board directive.”

She looked at him, this man who had detonated a wedding and then helped her stitch the city back together before lunch. “You were my father’s friend.”

“I was his lawyer,” James corrected gently, then amended, “and his friend. He snuck me cigars after meetings and pretended we were two men who weren’t married to our calendars.”

“Were you?” she asked, before she could stop herself.

“Married to my calendar?” He smiled. “I was. I’m a widower now. Two kids. Grown. One in Denver who thinks about mountains, one in Dorchester who thinks about restaurants. I think about all of it.”

Eleanor hadn’t had room for curiosity about the person reading her father’s last sentences aloud the night before. Now she did. “I’m sorry,” she said, and it wasn’t the reflexive social one—it was the old, heavy, I-know-that-landscape kind.

“Thank you,” he said, in the same dialect.

Dina appeared with a list. “Press wants a statement,” she said. “We can ignore them for a day, but we shouldn’t ignore them all the days.”

“Tell them this,” Eleanor said, and discovered she had already written the sentence in the back of her head: “Griffin Real Estate’s leadership transition is proceeding under court supervision. Our priority is simple: treat our tenants like neighbors and our neighborhoods like home.”

Dina’s pen scratched. “We can embroider that later,” she said, which was the highest praise an assistant ever gives.

Eleanor headed for the elevator. “I have to pick up my son,” she said, and nobody in the building told her she shouldn’t.

Noah bounded out of school with a backpack that seemed, improbably, heavier than that morning. It was snowing again, the flakes fat and elaborate. He launched into her. She caught him.

“How was being famous?” he asked, the way children ask a question and also give you the answer they’ve heard on the wind.

“I quit show business,” she said. “I joined real estate.”

“What’s that?”

“Houses,” she said. “And other people’s futures.”

“Can we have pancakes?”

“Yes,” she said. “Yes, we can.”

They cooked as if their kitchen had been briefly promoted to diner. Noah measured flour with determination usually reserved for Lego. He broke one egg and then apologized to the world. Eleanor warmed the pan and wished there were a step-by-step for this part too, something with checkboxes that ended in Family. While the first pancake bubbled, the doorbell rang.

James stood on the other side with a paper bag. “I brought blueberries,” he said. “And the kind of syrup that makes dentists rich.”

Noah peered from behind his mother’s leg, the international position of small skeptics. “Are you a judge?” he asked.

“Worse,” James said. “I’m a lawyer.”

“Do you know the rules of Monopoly?” Noah demanded.

“I know the rules,” James said gravely. “I do not always follow them.”

Noah considered this and then stepped aside. “You can come in.”

They ate pancakes that defied physics by being both fluffy and apologetic for a day that had required too much adulting. Noah told James about fractions. James told Noah about a building on Tremont that looked like a stack of books and made you want to whisper. “We’ll go see it,” he said, and Eleanor felt something in her unclench at the idea of a future plan that wasn’t a legal filing.

After Noah’s bath, after the story, after the light left on and the solemn promise to check back in ten minutes, Eleanor stood by her small living-room window with James while the city pretended to be a snow globe.

“You should know,” James said, his voice at that just-for-two register, “Martha and Victoria’s counsel called. They’ll fight in the press. They’ll frame this as a hostile takeover by a barista with aspirations. It’ll be ugly. Less ugly than last night.”

“I can survive ugly,” Eleanor said. “Cute nearly killed me.”

He smiled. “Your father would have hated the spectacle, loved the outcome.”

“He would have told me not to gloat.”

“Then don’t,” James said. “Build. It’s a better verb.”

She looked at him, at the lines near his eyes that said I’ve smiled often and not always because I had to, at the patience in his shoulders. “Why did he pick you?” she asked. “Not the firm with the hyphens.”

“Because I said no to him once,” James said. “Early on, when he wanted to do something that would have felt good and looked bad. I told him I didn’t work for men who wanted me to make their mistakes legal. He stopped, thought about it, and hired me the next day.”

“My father respected no,” she said. “It’s why he got so much yes.”

They stood quietly together, a tableau the snow approved. Somewhere on the street a car slid and recovered, the driver learning in real time the difference between velocity and control.

James cleared his throat. “Tomorrow we’ll start the audits in earnest. Frank will walk you through the portfolio. I’ll have a proposed press schedule for you to ignore. And—” he hesitated, then plunged ahead, “—there’s one more thing you should know. William asked me to make sure you didn’t forget your own life while running his. He made me promise to ask about Noah’s school concerts and your dentist appointments. He said you would try to be a company before you were a person.”

“That’s invasive,” she said, then laughed. “And accurate.”

“I’m a man of my word,” James said. “Prepare to be nagged about dinner.”

“We just had dinner.”

“Then breakfast,” he said. “Pancakes are an acceptable succession plan for one night. Not for every night.”

She shook her head and smiled into the window. The city had softened under its blanket. It was still sharp, still expensive, still a machine that turns people into anecdotes if you let it. But from here, with a lawyer who had ruined a wedding for her and a boy asleep in superhero pajamas, it looked navigable. It looked, impossibly, like home.

Her phone buzzed on the counter. A message from an unknown number materialized: This isn’t over. —V. Another followed a second later: We will see you in court and in society. —M.

Eleanor stared at the two sentences as if they were insects to be identified. She set the phone face down. “They’ll be loud,” she said.

“They always are, right before the quiet,” James said. “You just keep doing the next right thing. It’s devastating to villains.”

She exhaled. “One more question.”

“Shoot.”

“Do you really know the rules of Monopoly?”

“I do,” he said. “And I also know that free parking is a myth.”

“Blasphemy,” she said, deadpan. “Leave my house.”

He laughed, and for a long moment they let the joke do the work that needed doing. Then he reached for his coat. “Board meeting at five tomorrow,” he said. “Your board. Your meeting.”

“Bring coffee,” she said.

“I will,” he said. “You bring butter.”

After he left, Eleanor checked on Noah one more time, smoothing the hair from his forehead, the gesture a spell she would work for as long as he allowed it. In the living room, she picked up her father’s letter from the kitchen table where she’d set it down without realizing. She read it again, and when she reached the line about kindness mattering in business, she folded the paper along the crease it had chosen for itself.

At the window, the city breathed. Eleanor breathed with it. Tomorrow would be hard; the next day would, inconveniently, arrive right on schedule. There would be subpoenas and reporters and men who preferred their meetings with fewer women in them. There would also be tenants whose rent paid on time and in pride, and a little boy who would ask if elevators count as stairs.

She put out the light.

Somewhere, a snow plow passed, all muscle and inevitability, clearing a path she had not known she would need. Eleanor smiled into the dark.

“Okay, Dad,” she said. “We build.”

Part Three: Boardrooms and Blueprints

The morning light poured through Eleanor’s apartment like someone had decided Boston deserved a reprieve. It wasn’t mercy—Boston never trafficked in that—it was clarity. She dressed in a gray wool suit that had hung unworn since her college graduation and kissed Noah’s head before sending him off to school. “Board meeting,” she explained. “What’s a board?” he asked. “A group of people who try to tell you what you already know,” she answered, half-wry.

Tenant Tours

James insisted she start the day not with the board but with the buildings. “Numbers obey,” he said, “but tenants vote with their lives.”

So by eight a.m. Eleanor found herself in the lobby of a Griffin Real Estate apartment complex in Dorchester. The carpet was worn, the radiator clanked like a ghost with opinions, and Mrs. Alvarado from unit 2B appeared with a broom in one hand.

“You’re Bill’s daughter,” she said, eyes narrowing. “He used to sit right there.” She pointed at a battered chair near the mailboxes. “Asked me about my grandkids every week.”

“Yes,” Eleanor said. “I’m Eleanor.”

Mrs. Alvarado studied her as if checking for counterfeit. Then she nodded once. “Fix the elevator. It sticks on four.”

“I will,” Eleanor promised. And she meant it.

By ten, she’d heard about mold in a bathroom, a leaky roof patched with duct tape, and a tenant who wanted bike racks. She scribbled furiously in her notebook, realizing these voices were her true shareholders.

The Ambush

At five o’clock sharp, the board assembled again. Eleanor had prepared herself for resistance, but she wasn’t ready for the opening salvo.

“Ms. Griffin,” began Anthony Reese, one of the younger members with a résumé full of acronyms, “while we respect the court’s decision, the leadership transition has rattled investors. Perhaps we should consider appointing an interim CEO—someone with experience.”

The room murmured. Eleanor felt her jaw tighten. James slid a note toward her: Don’t flinch. Breathe.

She stood. “An interim CEO is a polite way of saying, ‘We don’t trust you.’ If that’s what you mean, say it. But also know this: tenants don’t care about your acronyms. They care that the elevator sticks on four. If I can solve that, I can solve a balance sheet.”

Frank Santos—the veteran—chuckled. “Spoken like Bill.”

Reese frowned, but the momentum shifted. “We’ll reconvene in two weeks to review progress,” he said stiffly.

“Good,” Eleanor replied. “By then the elevator will be fixed.”

Martha and Victoria Strike Back

That night, the Boston Herald ran with the headline: From Café to CEO: Can Eleanor Griffin Save Her Father’s Empire? The article quoted “sources close to the family” who described her as “inexperienced” and “out of her depth.” Martha’s fingerprints were obvious.

Victoria gave an interview to a society magazine, calling the will “a cruel trick” and describing Eleanor as “a barista with delusions of grandeur.” The comments section was brutal.

Eleanor sat at her kitchen table scrolling, stomach tight. “Mom?” Noah asked, climbing onto her lap. “Are they saying mean things?”

“Yes,” she admitted.

“Then stop reading,” he said simply. “They don’t know you.”

She closed the laptop. Sometimes truth arrives on a child’s breath.

The Pilot Program

Two weeks later, she presented her plan: a pilot “Rent-to-Own” program in two mid-size buildings. Long-term tenants could convert part of their rent into equity, building ownership over time.

Reese scoffed. “That will destroy cash flow.”

“No,” Eleanor said, pointing to charts. “It will stabilize it. Fewer vacancies, lower turnover, stronger communities. Stability pays.”

Frank leaned forward. “Bill always wanted to try something like this. He said landlords should make neighbors, not tenants.”

The vote was close, but it passed. Reese stalked out afterward, muttering about “social experiments.” Eleanor didn’t care. Progress was noisy.

The Gala

Three months later, the Hamilton family hosted a charity gala at the Museum of Fine Arts. Eleanor received an invitation addressed with frosty courtesy. “We should go,” James advised. “Visibility matters.”

She wore a simple black dress, nothing couture. Noah stayed home with a sitter. The room glittered with gowns, jewels, and champagne laughter. Victoria was there, radiant but brittle, clinging to conversations like life rafts. Martha hovered nearby, smile strained.

When Eleanor stepped in, conversations faltered. She was the scandal come to life.

Midway through the evening, the emcee invited donors to speak. To everyone’s surprise, Eleanor rose. “I won’t take much time,” she began. “But I’d like to tell you what Griffin Real Estate is doing with our resources. We’re investing in green housing, tenant equity, and the William Griffin Foundation for single parents. If anyone here believes business should serve more than bank accounts, we welcome your partnership.”

The applause started small, then grew. Not everyone clapped, but enough did. Reporters scribbled. Cameras flashed. Eleanor caught Victoria’s expression: shock, then something that looked almost like regret.

James met her at the edge of the crowd, offering a glass of water. “You just flipped the script,” he murmured.

“I just told the truth,” she said.

Noah’s Science Fair

Amid the chaos, Noah grounded her. His third-grade science fair was in March. His project: “Why Snow Melts with Salt.” The display board leaned, the lettering uneven, but his grin was steady.

When the judges stopped by, Noah explained earnestly: “Salt makes water freeze lower, so the ice melts. That’s why cities use it on roads. My mom says business is like salt—you can change things if you know where to sprinkle it.”

The judges laughed, impressed. Eleanor blinked back tears. Sometimes wisdom skips generations, sometimes it doubles back.

James’s Past

One evening after dinner, James lingered as Noah built Lego skyscrapers. “Your father loved this city,” James said. “But he also worried it would eat you alive.”

“You talk like you knew him better than I did.”

“I knew parts of him,” James admitted. “The stubborn parts. The parts that wanted to trust but couldn’t. He hired me not just as a lawyer. He made me promise to look out for you.”

“And you’re still keeping that promise?” she asked.

He met her eyes. “Yes. Though now… maybe it’s less a promise, more a choice.”

Her heart skipped. For seven years she’d been mother, worker, survivor. The idea of choosing something else—someone else—was terrifying. And exhilarating.

A Company, a Cause

By spring, Griffin Real Estate was in headlines again—but this time for its tenant programs and green initiatives. Investors grumbled, but the city noticed. Tenants called her “the daughter who came back.”

At a press conference, Eleanor stood behind a podium with the company logo. “We are not just building properties,” she declared. “We are building futures. My father believed in kindness as a business strategy. I intend to prove him right.”

The applause was real. For the first time, Eleanor believed she could stand not just as William Griffin’s daughter, but as herself.

That night, she tucked Noah in. “Mom,” he said drowsily, “Grandpa must be proud.”

She kissed his forehead. “I hope so.”

From the living room, James’s voice called softly: “He is.”

Part Four: The Reckoning and the Rest

Boston thawed into spring with its usual reluctance—potholes yawning open, slush puddles lying in ambush, commuters rediscovering sunglasses like artifacts. For Eleanor, the season carried both relief and dread. Relief, because Griffin Real Estate was stabilizing. Dread, because Martha and Victoria weren’t done.

The Counterattack

It began with a lawsuit filed in Suffolk County Court: Martha and Victoria Griffin v. Eleanor Griffin. The claim: undue influence, forged documents, breach of fiduciary duty. The tabloids pounced.

“From Café to Courtroom,” blared one headline.

Eleanor read it at her desk, Noah’s school photo pinned to her corkboard for ballast. James entered with a folder under his arm and a calm expression honed over decades of drama.

“They’re grasping,” he said. “But it’ll be loud.”

“I can survive loud,” Eleanor answered, echoing herself. “We’ve survived worse.”

The Courtroom

The courtroom was nothing like the Regent Plaza ballroom, though the stakes felt eerily familiar. The wood paneling smelled of polish and history. Reporters filled the gallery like crows.

Martha, in a navy suit too expensive for her new means, sat rigid beside Victoria, who was dressed in pale beige, as if neutrality could be worn. Their lawyer spoke of “family betrayal” and “manipulated documents.”

James rose slowly, deliberate as dawn. “Your Honor,” he began, “this is not a case about law. The law is settled. This is a case about resentment dressed as righteousness.”

He produced William’s handwritten letters, authenticated by experts. He presented years of financial records showing Martha and Victoria siphoning company assets. He introduced testimony from long-time executives who confirmed William’s intent.

When Eleanor took the stand, her hands trembled only once—when asked why she thought her father left her the company.

“Because he trusted kindness,” she said simply. “And he knew I would not let it be mocked.”

Silence, heavy and complete. Even the judge looked moved.

The Verdict

After three days, the judge ruled decisively: the will was valid, Eleanor the rightful heir, Martha and Victoria liable for restitution. Their lawsuit collapsed like paper in rain.

Outside the courthouse, reporters swarmed. Microphones jutted like spears. Eleanor stood tall.

“My father believed business should serve people,” she said. “That is what Griffin Real Estate will continue to do. As for family… forgiveness is possible. Forgetting is not.”

The quote made front pages across New England.

Martha and Victoria’s Fall

The verdict left Martha and Victoria stripped of wealth and reputation. They moved to a modest apartment in Revere, commuting on the T, learning coupons and bus schedules. Victoria found clerical work at a small brokerage. Martha discovered, belatedly, the humility of laundry.

One evening, Victoria whispered, “Do you ever think Dad was right?”

Martha sipped weak tea. “I think,” she said slowly, “we ran out of mirrors that lied back to us.”

A Visit

Three months later, they came to Eleanor’s office unannounced. Dina raised an eyebrow but let them in.

Eleanor looked up from her desk, her posture now the posture of a CEO who understood her own authority.

“Mother. Victoria.”

Martha’s voice cracked. “We came to apologize.”

Victoria added, tears catching in her lashes, “We did terrible things. At the wedding, with Dad’s will—”

Eleanor held up a hand. “The past cannot be repaid. But it can be redirected.” She slid documents across the desk. “I’ve arranged a stipend for you both. Modest. Enough for rent and groceries. In return, one condition: you meet with Noah once a month. He deserves to know his grandmother and aunt.”

For the first time in years, Martha’s tears were not for herself. “Thank you,” she whispered.

New Directions

With the lawsuits behind her, Eleanor launched Griffin Real Estate into a new era. Environmentally friendly housing developments broke ground in Roxbury. The rent-to-own pilot expanded. The William Griffin Foundation held its first fundraiser, Noah cutting the ribbon with awkward solemnity.

“Mom,” he said, “I want to help people like Grandpa did.”

“You already are,” she replied, hugging him.

The city noticed. So did investors. Griffin Real Estate became known not just for profits, but for purpose.

Eleanor and James

Their professional relationship had blurred quietly into something more. Dinners after long meetings became routine. Baseball games with Noah became tradition. One evening, as they walked along the Charles, Eleanor asked, “Why did you stay all these years? Even before my father died?”

James smiled, lines deepening near his eyes. “Because William made me promise to watch over you. But now—” he paused—“now I stay because I want to.”

The air between them shifted, warmer than the breeze. Eleanor laughed softly. “You ruin parties, but you keep promises.”

“Two marketable skills,” he said.

The Christmas Gathering

Snow fell thick on Christmas Eve. Eleanor’s new house glowed with lights. Around the tree sat employees, friends, Noah’s classmates, and—yes—Martha and Victoria. They were subdued, humbled, but present.

James raised his glass. “To futures we didn’t expect.”

Noah lifted his cocoa. “To pancakes shaped like M’s.”

Laughter rippled through the room. Eleanor smiled, her eyes catching James’s across the tree. Their bond, once professional, had deepened into something steadier—love born not of fairy tales, but of storms weathered together.

By the window, Noah held his grandfather’s photo. “Mom, I never met Grandpa. But he must have been a good man.”

Eleanor hugged him. “The best. And he’s still watching over us.”

Outside, snow fell on Boston, soft and relentless, covering scars and sidewalks alike. Inside, warmth spread—proof that families could fracture and still reform, that legacies could bend and still stand.

The Clear Ending

Eleanor Griffin, once the overlooked daughter pouring coffee in a café, now stood at the helm of her father’s company, a mother raising a boy her father would have adored, and a woman who had learned to meet cruelty with dignity. She hadn’t erased the past. She’d rewritten it.

Snow whispered against the glass, and she whispered back: “We build.”

News

My obstetrician husband felt my sister’s baby bump – then demanded an ambulance

Part One: Maple Avenue in Autumn Columbus in October looked like a postcard someone forgot to mail. Maple Avenue wore…

My parents and sister pushed me and my 6-year-old son off a cliff.

Part One: The Hike Willowbrook, Ohio was the sort of town that made postcards feel like they’d been eavesdropping. Spring…

At my sister’s wedding, she and my mother mocked me, calling me a single mother and a used product…

Part One: Numbers and Shadows The sound of calculator keys echoed in Aaron Johnson’s small home office like a quiet…

My mother-in-law sent me chocolate for my birthday, but my husband ate all of it…

Part One: The Birthday Box The heat in Boston didn’t knock; it moved in and asked what was for dinner….

James Corden Returns to U.S. Late-Night — And He’s Joining Former Rival Seth Meyers

After more than a year away from American late-night TV, James Corden is making his comeback. The former Late Late…

Greg Gutfeld Says Late Night Ignored Viewers — and He Cashed In: ‘There Was Free Money on the Table

Greg Gutfeld has never shied away from stirring the pot. The Fox News personality turned late-night disruptor is once again…

End of content

No more pages to load