Part One: The Wedding Weather

The October sun did its best imitation of June, pouring a mild, honeyed light over the parking lot of the Grand Harbor, a venerable Boston-area hotel that had been hosting proms, fundraisers, and forever-after promises since Eisenhower. Emily Chambers tightened her grip on her son’s hand and smoothed the wrinkled knee of her black dress the way mothers smooth time—quickly, ineffectually, lovingly.

“Mommy, is my tie okay?” Jacob asked, palm pressed to his small chest like a miniature senator about to filibuster.

“Perfect,” Emily said, leaning down to kiss his cheek. The tie was crooked in a way that made his five-year-old earnestness ache to be protected forever. She fixed it with two fingers and a smile. “Handsome as your dad.”

Michael. Saying his name in her head was like brushing a bruise—still tender after three years, but proof that the skin had healed enough to feel. An architect who collected blue pencils and sunrises, who could fold paper cranes with the patience of a saint and the precision of a surveyor. He’d left behind an insurance policy, a legend of kindness, and a hole that had its own weather systems.

Inside, the lobby was a ballroom’s preamble—tile floors polished to the point of vertigo, florists hustling like choreographers, a pianist trilling something cheerful near a ficus that had seen better centuries. A gaggle of cousins materialized like a pop-up ad, and then Aunt Dorothy swooped in with the finesse of an ambulance chaser and the volume of a marching band.

“Emily, it’s been ages! You’re so thin! Are you eating?” Dorothy demanded, her bracelets applauding themselves.

“I am,” Emily said, amused more than annoyed. Grief had whittled her at first; motherhood and work had toned what was left. She didn’t owe anyone a treatise on macro-nutrients.

“And this must be Jacob,” Dorothy said, bending to the boy. “Last time I saw you, you were a marshmallow. Now look—your dad’s face all over again.” Her voice gentled on the last bit.

Jacob tucked himself behind Emily’s leg like a bookmark. He remembered his father in pieces: the sound of footsteps upstairs, a laugh in the next room, a familiar smell on an old sweater. Children carry memory like a pocket stone—a small, smooth thing they rub when the world is big.

The reception hall doors yawned open to a scene that could have floated straight out of a bridal magazine. White and blush flowers, gold-rimmed plates, chandeliers that held light the way good marriages hold secrets—carefully, with a certain flourish. Emily clocked the place cards, the dessert table mocking portion control from across the room, the way someone had set a tiny heart of rose petals at each setting like a flourish from Cupid’s intern.

And then Margaret appeared, as if conjured by the word “family.” Retired teacher, pearl earrings, voice calibrated to the frequency of confidence and casseroles. “Emily, sweetheart.” Her hug was soft, powdered, firm enough to tamp down argument.

“Hi, Mom,” Emily said, returning the press of shoulder to shoulder.

“Jacob, my darling.” Margaret plucked her grandson up with a flourish and produced a small paper bag the way magicians produce doves. Out came a toy: a red sports car so glossy it might have filed its own insurance claim. “Vroom,” Margaret said, as if sound effects were a love language.

Jacob’s eyes lit like matchheads. “Thank you, Grandma.”

Emily smiled despite herself. Her mother’s love was a tidal thing—comforting when it rolled in, overwhelming when it slammed against the rocks. She wasn’t blind to the blessing; she also wasn’t oblivious to the undertow.

“By the way,” Emily said, making sure the words were unmissable, “you told the planner and the chef about Jacob’s shrimp allergy, right?”

Margaret’s expression arranged itself into competence. “Of course. I told everyone with a clipboard. Special children’s menu, no shellfish, separate utensils, yada yada. You know me.”

Emily did. And yet.

Jacob parked the red car near a butter knife and began mapping the table’s topography—the folded napkin a mountain, the bread plate a plain, the water glass a blue lake he could skirt with squeaky tires. The sound was soft, the kind of squeak that makes parents fond and childless guests reconsider their stance on family-friendly seating charts.

Relatives arrived in amiable squalls. There were hugs and oh-my-gods and look-at-yous. Emily made the appropriate cheerful noises while her internal antennae kept pinging Jacob’s location. She had become both mother and security detail since Michael died—sweetness in one hand, vigilance in the other.

The ceremony arrived right on time, like a train at a station that is proud of itself. The doors swung, and there was Robert, her stepfather—Margaret’s second husband, Sophia’s biological father—escorting the bride’s party with a practiced composure. Emily respected Robert in a quiet, chilly way. He’d never been unkind; he’d just never been hers.

And then Sophia stepped into view in a white dress so exacting in its lines you could do Euclidean theorems on it. Lace sparkled, beads chimed under the lights like captured raindrops. She was every adjective a wedding ad campaign has ever promised—radiant, elegant, breathtaking—and also simply Sophia, the baby sister who had spent childhood turning the ordinary into a runway.

“Beautiful,” Jacob whispered, reverent as a parishioner.

“It’s true,” Emily said. Admiration, unalloyed, came easy in moments like this. Sophia had always been the sunbeam to Emily’s shaded porch: bigger laugh, quicker eyes, a gift for entering rooms like a lyric. Emily had long since learned that you can love day even if you live in dusk.

The groom—David Harrison, thirty-five, investment guy with the posture of a man who believes numbers should salute him—looked wrecked with happiness as the minister warmed up his vowels. Vows were exchanged, rings previewed their careers as magnets for dish-soap and admiration, and somewhere between “…to have and to hold…” and “…as long as we both shall live,” Emily felt the reliable sting at the corners of her eyes. Beside her, Margaret dabbed, meticulous even in moisture.

Jacob placed his car on his lap like a solemn offering and watched the altar with a seriousness that made Emily’s chest ache. He was a shy kid, yes, but he knew things—about absence, about the way promises sound when you desperately want to believe them.

Applause. A kiss. A recessional scored by strings and the low punctuation of someone’s uncle’s squeaky shoes. And then the crowd flowed back toward the reception, that second chapter where love pivots from poetry to logistics: seating, salads, speeches.

The family table gathered: Margaret, Robert, a few Chambers cousins trying out adulthood like a new suit, Emily and Jacob with the red car now dispensing routes along bread crumbs. The room glowed. Speeches trundled forward with predictably charming stumbles—groom’s father toasting Sophia’s kindness, Robert calling his daughter “sunshine,” and, in the couple’s own turn, Sophia saying the kind of things that pry open a heart.

“Mom, Dad, Emily,” she said, glancing at each while David squeezed her hand under the tablecloth like punctuation. “Thank you. Emily… you’ve always given me the exact advice I needed when I didn’t know what to do. And after Michael… watching you stay strong—well, it taught me what family is.”

Emily’s throat tightened for a reason that had nothing to do with she-cried-at-the-AT&T-commercial tenderness. There it was: acknowledgment. Not as currency, but as truth. She nodded once, the sort of nod that means we are complicated and also we are here.

“Are you tired?” Margaret murmured shortly afterward, fingertips light on Emily’s shoulder. “You look pale. Have you been eating? Maybe go easy on the wine.” The maternal concern came in steady drips—too sweet, too frequent.

“I’m fine,” Emily said, and she mostly was. Work had been a treadmill recently, Jacob had a cough last week, and life has a way of thinning you out in the places you used to be padded. But there was nothing wrong beyond the usual wrongness of being a person on the planet.

Jacob kept to his lane—red car, tight laps, the occasional up-look to check that his mother still existed. When laughter popped from the kid table, he glanced over with interest but stayed tethered. Loss makes certain leashes invisible and unbreakable.

The evening loosened its tie. Friends performed a dance halfway between TikTok and sincerity. The bride and groom did a twirl that promised better twirls later. Margaret continued to hover over Emily’s water glass like hydration was a moral virtue.

And then the culinary procession began—first courses clearing out, the promise of mains hovering in a delicious fog from the kitchen doors. A young waiter stopped to reassure Emily, unprompted, that the children’s plates were entirely shellfish-free. “Special menu,” he said, brisk and proud. “We’ve got it.”

“Thank you,” Emily said, meaning it.

Jacob, bored in that way only five-year-olds can be in a room that cost a car payment to decorate, invented a new game: red car mountain drops. He’d roll the car to the table’s edge and let it plunge into the carpeted abyss, squealing quietly as it disappeared, then lean over like a spelunker to retrieve it.

“Careful, buddy,” Emily warned, amused. Some hazards are part of childhood, and some are sneaking in through the service entrance.

On the third descent, the car took a heroic bounce and zipped under the tablecloth like a scarlet fish. Jacob ducked after it, indignant and thrilled. The space under the table was small, a world of chair legs and purse straps and the whisper of adult shoes doing their adult clicking. He crawled and grabbed and found the car near a forest of high heels. And then he noticed it: a small white folded paper near his grandmother’s handbag.

He didn’t read much yet, but he read some, and kids are anthropologists of the floor. Jacob picked up the paper, flipped it open, and sounded out syllables as if decoding a secret quest.

Table eight. Please add shrimp to the main dish. Don’t worry about allergies.

M.

He knew the number eight. Their place card had a happy little eight on it. And he knew the word shrimp—capital-K Known. Shrimp was the dragon in the story. Shrimp was up there with “Don’t touch the stove” and “The street is not a playground.” Shrimp was why waiters had to know Jacob’s name and why his mom carried a pen-shaped injector in her purse like a superhero’s wand.

His chest fizzed in a way that wasn’t fun. Children can’t articulate dread; they wear it. He scrambled upright, clutching the note and the car, and tugged at his mother’s sleeve with the urgency of an alarm bell politely requesting attention.

“Mommy?” His voice came out thinner than usual, a string pulled taut.

“Did you find your car?” Emily asked, turning, smile already prepared, a pat, a kiss, the whole maternal kit. Then she saw his face and the smile shelved itself.

“Mommy, let’s go home,” Jacob whispered. Not pouted. Not whined. Requested, the way a person requests water in a desert.

“What’s wrong? It’s almost dinner, pal.” She searched his face for fever, for tears she’d missed.

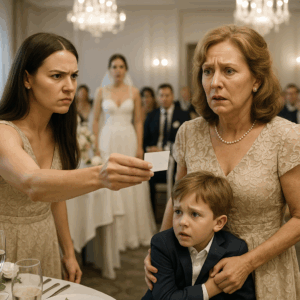

He offered up the folded paper with two hands, as if handing over a live thing. Emily took it, read it, read it again. The world didn’t tilt. It shifted, like a floor that had been level only because you never looked too closely at the bubble in the carpenter’s tool.

Table eight. Please add shrimp to the main dish. Don’t worry about allergies. M.

Her first thought arrived sensible and soldierly: Jacob. Keep Jacob safe. Her second sprinted in behind: Margaret? Her third knocked the wind out of her in a way that had nothing to do with air: Why?

She lifted her head and scanned the room. Margaret was ten feet away, performing grandmotherly conviviality with signature flourish, a hand on someone’s forearm, the laugh that said love and competence and those lemon bars everyone asked about. Sophia shimmered two tables over, radiant as advertisement, David leaning in to listen like a man auditioning for the part of husband. Everything looked perfect, which is how you know something isn’t.

The servers emerged with the mains, plates like flying saucers balanced on forearms. Timing is everything in kitchens and in ambushes.

Emily stood, her chair skittering an inch. “Jacob,” she said calmly, in the tone that means don’t argue, “we’re leaving.”

Margaret turned, sensing disturbance the way cats sense weather. “Leaving? Now? Dinner is just—there’s a special dessert for Jacob.”

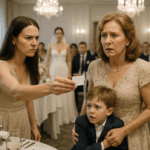

Emily held up the note. “Explain this.”

For a moment, the air between them was a taught string, singing at a frequency that only the two of them could hear. Margaret’s face—carefully arranged for decades in explicitly maternal lines—misfired. A flicker, then pallor, then something that was not confusion and not remorse so much as recognition.

Behind them, the scene tried to continue. Clinks, chatter, the music doing its job of covering sounds that don’t belong at weddings.

Emily’s mind moved at the speed of survival, connecting dots that had been scattered like confetti. Margaret’s hovering all day. Her granular questions about Emily’s water intake and sleep and wine. Her insistence on being the messenger to staff. The way she had positioned herself as the calm in all storms—as if the storm needed an anchor to lash itself to.

Three years ago, when the car crossed the yellow lines and Michael didn’t come home, an insurance agent had handed Emily a brochure that talked about stability like it was an appliance you could buy. The policy was generous. Jacob was the beneficiary; Emily the guardian. If something happened to her, the guardianship—and the funds for Jacob’s future—would pass to the next named adult in line. Family. The word felt jagged suddenly, as if it had been misspelled and she was only noticing now.

“Mom,” Emily said, her voice cold enough to flash-freeze a pond, “we’re leaving.”

Margaret tried for confusion again; her face refused the assignment. “Sweetheart, you’re over-tired. Let’s get you some—”

Sophia materialized, dress gathered in one hand, alarm gathering in the other. “Emily? What’s going on? You can’t just—my wedding—”

Emily turned to her sister, and something inside her snapped cleanly, like a dry twig. “Congratulations,” she said, voice flat. “It was beautiful.” Then she took Jacob’s hand and made for the exit with the smooth, uncompromising momentum of a tide.

They didn’t get far.

“Emily, wait,” Margaret called, running in heels that had never met urgency. Sophia followed, David lagging at the edge of the scene like a man deciding whether this was his movie.

In the lobby, all that chandeliered light looked different. The hotel’s expensive hush made drama sound cheap. Emily pivoted. Jacob wrapped his arms around her neck and tucked his face away from the grandmother he knew and suddenly did not.

“What is this?” Emily asked, holding the note out like a crucifix at a vampire. “Table eight. Add shrimp. Don’t worry about allergies. ‘M’ for what? Murder?”

“Emily,” Sophia whispered, blanching as the sentence’s meaning assembled itself. “Is that—Mom?”

The room held its breath. A couple nearby, strangers in formalwear, stopped pretending not to listen.

Margaret pressed trembling fingers to her lips, an actress about to deliver a monologue she didn’t rehearse because she never planned to speak it. And then she began to cry. Not dab-dab society tears. Cracked, gulping sobs that shook the pearl earrings.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m sorry. Not here. Please. Not—” She glanced at the crowd, at the phones that might as well have been live feeds. “A private room.”

Emily shouldered the choice she did not want. Privacy meant more time in the blast radius; publicity meant burning everyone. She chose the smaller fire.

They were shown to a tucked-away lounge with more art on the walls than anyone was looking at. Sophia’s veil floated behind like a torn cloud. David promised to stall the guests with platitudes and the open bar, then volunteered to rejoin the happy couple later in a tone that sounded like a man offering to hold a bomb.

Margaret sat, then stood, then sat again, a woman rebooting. She wiped her face and inhaled in a way that said pedagogue about to explain fractions to a hostile classroom.

“It’s about the money,” she said finally. “Michael’s insurance. Jacob the beneficiary. You as guardian. If something happened to you—”

“I know how it works,” Emily said, the words razor-thin.

“There are things you don’t know,” Margaret pushed on, voice trembling but determined. “Sophia’s marriage… David’s company went under months ago. He’s drowning in debt. He came to me. He said he needed help, that if we didn’t step in—” She choked. “He said no wedding.”

Sophia’s hand flew to her mouth. “What?”

“He presented it like a transaction,” Margaret said miserably. “A dowry by another name. I told him we are not that kind of family. He said families are whatever they can afford to be.”

Silence. The hotel AC hummed with corporate indifference.

Emily felt Jacob’s heartbeat against her collarbone, small and insistently alive. The math tried to resolve itself in her head—the memo, the hovering, the policy. The conclusion arrived not with epiphany but with the exhausted certainty of two plus two.

“So the plan,” Emily said quietly, terrifyingly calm, “was to endanger Jacob, create chaos, and while he was hospitalized, you’d—what? Dose me? Stage an accident? Solve a problem the way people write off bad debt?”

“No,” Margaret protested, the denial so fast it tripped. “Not Jacob. I swear. I—” She faltered and looked at the note, that small white rectangle that said the quiet part loudly. “It wasn’t supposed to— I thought a scare—” She stopped. Even lies refuse certain contortions.

Sophia stood, veil trembling. “You were going to hurt my sister? For my wedding? For a man with a balance sheet where his heart should be?”

“I was trying to protect you,” Margaret cried, reaching blindly, palms empty of good answers. “I was cornered.”

“Cornered is a shape,” Emily said. “So is a coffin.”

“Emily,” Sophia whispered, eyes glossy with a pain that wasn’t mascara-friendly. “I didn’t know.”

“I believe you,” Emily said, and she did, because whatever else Sophia was, she had never been the architect of malice. “But belief isn’t a blanket. It doesn’t fix cold.”

Margaret stood, wobbling. “He threatened me, Emily. He said if we didn’t help, he’d walk. He said—”

“If threatening you makes him walk,” Emily said, “maybe you let him put his feet to use.”

Sophia’s face crumpled. “What do I do?”

“You decide,” Emily said, shifting Jacob’s weight on her hip, the boy’s red car wedged between them like a talisman. “You decide whether you want a marriage or a repayment plan.”

Margaret reached out. “Please don’t take Jacob away from me. He’s my grandson.”

“You tried to make him a casualty,” Emily said, and of all the sentences spoken that night, this one felt like the hinge. “We’re leaving.”

She turned. Sophia moved as if to follow, then froze, the way people freeze when they realize the floor plan of their entire life isn’t to code. Margaret’s sobs swelled and emptied. Somewhere far down the hall, a DJ cued a song about forever.

Emily walked back through the lobby, past the flowers that hadn’t done anything wrong, under lights that would glitter long after tonight’s guests had traded heels for flip-flops and vows for laundry. Outside, the air was colder, honest. She buckled Jacob into his booster with hands that trembled only after they were done doing the job.

“Mommy?” Jacob whispered as she slid into the driver’s seat. “Won’t we see Grandma anymore?”

Emily put a hand on his hair, soft and warm and here. “That’s right, Jacob.”

He thought about this in the solemn way children do, turning the idea over in his mouth before swallowing. He nodded, the quietest acceptance. “We have each other,” he said, not as consolation but as inventory.

“That’s enough,” Emily agreed, and then she turned the key, and then she drove, and the hotel receded in the rearview mirror like a postcard someone else had mailed.

In the front seat, the red car waited on the dashboard, facing forward.

Part Two: The Note and the Numbers

The drive home felt like navigating with a compass that refused to settle. The road signs kept doing their job—EXIT 22, MERGE LEFT, NO U-TURN—but none of them said the thing I needed most: THIS WAY OUT OF WHAT JUST HAPPENED.

Jacob fell asleep six minutes into the trip, thumb tucked in the old habit he’d mostly outgrown. The red car perched on the dashboard like a tiny hood ornament deputized for morale. I kept one eye on the rearview, half expecting a convoy of florists and accusations to follow us down the Pike.

We made it to the apartment without being chased by bridal bouquets. I carried Jacob in, weight heavy and comforting against my shoulder, and tucked him into bed fully dressed, the way you tuck in the day when it’s misbehaved. He breathed that sleep-breath that smells faintly of sugar and clean laundry. I stood there long enough to memorize it, then closed his door and walked to the kitchen table with the memo in my hand and a glass of water I forgot to drink.

Table eight. Please add shrimp to the main dish. Don’t worry about allergies. M.

I tried to imagine alternate universes where that M stood for anything other than my mother. Masonry? Metaphor? Miracle? The loops of Margaret’s handwriting were as familiar as the pattern of freckles on my own wrist. The more I stared, the more the paper felt hot. Evidence does that—it sits there, quiet and obscene.

I took pictures. Front, back, close-up, a shot with a quarter for scale like a true-crime podcast had rented out my kitchen. I emailed the photos to myself and to a brand-new folder named “Jacob—Safety,” then printed a copy for good measure. The printer chattered like a tattletale. When it stilled, the apartment was very, very quiet.

I called the Grand Harbor. A manager with a voice smoothed by decades of appeasing the aggrieved came on the line. I told him what I had, and what it might mean, and what I had reason to believe was about to happen to his Yelp reviews if he didn’t take me seriously.

He took me seriously. “Ms. Chambers, I’m so sorry. We’ll preserve the footage from all cameras covering the kitchen, service hallway, and ballroom. I’ll notify our head of security and our food and beverage director. Please file a police report first thing. If you prefer, I can call them now.”

“No,” I said. “I’ll call.”

“Again—our apologies. And—” He hesitated, as if consulting a manual that didn’t have a chapter for this. “Congratulations on your sister’s wedding?”

“It’s been a day,” I said, and he made a sympathetic noise that managed to be both insufficient and kind.

I dialed the non-emergency line. The dispatcher asked for my address, then my story, then my name, spelled slowly as if accuracy could save us. “An officer will reach out in the morning,” she said. “If you feel unsafe tonight, call us back and we’ll send a patrol car to do a drive-by.”

The phrase sounded like it had taken a wrong exit from another genre of story. “We’re okay,” I said. “I have deadbolts and rage.”

She laughed, softly. “That’s a start, ma’am.”

I texted one person: Liv, my neighbor, a nurse who collects vintage Pyrex and appears at precisely the right moments with precisely the right casseroles. If you see my mom, don’t buzz her in, I wrote. Long story. Will explain tomorrow. We’re okay. She replied with a thumbs-up and a flexed bicep. Sometimes the right answer is an emoji that refuses collapse.

By midnight, the apartment had settled into that late-hour creakiness old buildings get, like they’re telling you their secrets if you’ll just stop talking long enough to listen. I sat with the memo and the insurance policy folder and the spool of years that led to the moment my mother decided an “M” could stand for malice.

Michael had been thorough. The policy named Jacob as beneficiary, me as guardian, Margaret as successor guardian if I became unable to serve due to death or incapacitation. We’d picked Margaret because she’d practically raised half the neighborhood and because on paper she was what you want in a guardian: stable, retired, a woman whose refrigerator notes were legible and whose calendar had a color for everything.

On paper. Paper had betrayed me twice tonight.

I slept in the chair by Jacob’s door, in a position the human body should not attempt and mothers do anyway. I woke to his whisper. “Mommy? Are we going to school today?”

“It’s Sunday,” I said, confused enough to check my phone twice. Time had taken a knee.

He nodded, relieved. “Can we have pancakes?”

“Absolutely.” Comfort is a carbohydrate.

We mixed batter and made a mess and burned the first one in honor of his father, who had once declared the initial flapjack a sacrificial offering to the gods of consistency. Jacob giggled, a sound that lacquered the moment against scratch. For twenty minutes, the world held together: fork clinks, syrup negotiations, the red car doing dignified laps along the placemat while its owner chewed.

Then my phone rang. “Detective Rios,” the caller said. “Cambridge PD. Can we talk?”

He came by late morning. Mid-forties, wedding ring, a notebook that looked as if it had been chewed by a dog and loved anyway. He listened as I told the story, with a patience that wasn’t performative. He took the memo with gloved hands and slid it into a plastic sleeve. He asked about the allergy, about the time I’d nearly died at a fusion restaurant that thought peanut oil was a universal solvent, about our table number. He asked if Margaret had ever displayed—he paused, searching for a word that wasn’t going to get him chewed out by HR—“poor boundaries.”

“Yes,” I said. “But nothing like this. Until this.”

He nodded, as if confirming a hypothesis he hated. “We’ll want statements from the hotel staff. If the kitchen got any verbal instructions about your table, we’ll find out. Cameras should give us something. It’ll help that the Grand Harbor’s security is better than most banks. Weddings bring out thieves and saints.”

Jacob watched Detective Rios from the couch, solemn as a judge, red car parked on his knee. When Rios was done, he crouched to eye level. “Hey, buddy. I’m a police officer. My job is to keep people safe. Your job is to be five.” He pointed at the toy. “Is that a Lamborghini?”

“Ferrari,” Jacob corrected, all business. “It’s red.”

“Best color for speed.” Rios stood, returned to adult height. “Ms. Chambers, think about a restraining order. Even if this never goes to indictment, it gives you a path to call if she shows up anywhere near you.”

“I’ll talk to a lawyer,” I said, and felt something unclench. A plan is a handrail.

After he left, I called Michaela Chen, an attorney I knew tangentially through a client who’d once tried to deduct his therapy dog as a business expense. Michaela’s specialty was family law with a minor in miracles. She answered on the second ring with Sunday cheer. I gave her the Cliff’s Notes version. She swore—elegantly, creatively—and then laid out steps: emergency order of protection, documentation, copies to the school and daycare, notifications to pediatrician and anyone who might hand Jacob food.

“If you have to be petty,” she said, “be strategic petty. Change the doorman list. Have your super confirm building policy. Tell friends not to engage. Don’t post.”

“I don’t post,” I said. “I’m a private person with a very loud family.”

“I’ll email the forms. Come by tomorrow at nine and we’ll file in person.” She paused. “Emily, I’m sorry. I’ve seen a lot, but this—this is engineered.”

Engineered. I thought of Michael’s careful blueprints—clean lines, clear flow, everything where it belonged—and felt my throat go tight. “Thank you, Michaela.”

By afternoon, the wedding had found me anyway. A text from an unknown number: How could you? No name, but the punctuation smelled like a cousin who’d majored in theater. I blocked, muted, deleted, in that order. Another ping: We need to talk. Sophia. I stared at the name until it went out of focus.

Come by at five, I typed. No Mom. Three dots appeared, then disappeared like second thoughts. Okay. David is with me. Is that—?

No David, I wrote. Just you.

When the knock came, Jacob was on the rug building a city out of blocks—skyscrapers, roads, a well-planned park. He looked up, wary. “Is it Grandma?”

“No,” I said. I glanced through the peephole at a bride in jeans and a hoodie, her hair scraped into a bun that made her look sixteen and exhausted. I opened the door.

Sophia stepped in and did a scan the way sisters do when they’re trying to count visible damage. She took in Jacob, the clean kitchen, the memo on the table in its plastic sleeve like a butterfly we meant to pin. She swallowed.

“Em,” she began, and then stopped, because the thing in her throat wasn’t words. It was grief with its shoes on.

“I believe you didn’t know,” I said. “Start there.”

She nodded, relief washing some color back into her face. “David—” she started, then faltered. “That is, the man who has now discovered the true meaning of ‘return to sender’—he lied. A lot. About everything. He told me the company took a hit but was fine. He told me the investors were patient and sophisticated. He told me—” She laughed once, a sharp sound that wasn’t humor. “He told me we were a team.”

“You were,” I said. “He was on offense; you were the stadium.”

Her mouth twisted; she nodded. “After you left, I asked him straight up about the debt. His answers leaked. I called a friend at the firm where he used to work. There was an investigation. There were… words like ‘misrepresentation’ and ‘commingling.’ He was going to ‘fix all of it’ after the wedding. Apparently, marriage was his rebrand.”

“Branding works best when the product isn’t rotten,” I said, and she huffed a laugh that turned into a sob.

“I didn’t know about Mom,” she whispered. “She kept saying she’d ‘handle things.’ I told her I didn’t want money. I told her we could downsize, wait, elope, anything. She smiled that smile and told me to enjoy my day.”

“Her definition of ‘handle’ needed a warning label,” I said. “Like fireworks.”

Sophia sat, back straight because posture is the last dignity some days. “What do you need from me?”

“Distance,” I said. “From Mom. From anyone who thinks this has a spin that makes it better than it is.”

“Done.” She exhaled, nodded once like she was taking an oath. “I’m staying at a hotel tonight. I called a lawyer. I’ll file for annulment tomorrow. I can’t fix what she tried to do, but I can refuse to build anything on it.”

Jacob put a block on his tallest tower and turned to us with the solemnity of a city planner facing a zoning board. “No shrimp,” he announced, a rule and a diagnosis.

“No shrimp,” Sophia echoed, voice breaking. “Jacob, I’m so sorry.”

He blinked at her, then returned to infrastructure. Forgiveness, I’ve discovered, is sometimes an economic policy of energy efficiency.

After she left, the apartment felt larger. The kind of larger that has weather. I sat at the table and filled out Michaela’s forms while Jacob narrated a car chase between red and a blue block that was pretending to be a police cruiser. We ate leftovers and the ice cream Aunt Dorothy would have lectured me about, then brushed teeth and read about a bear who moves to a lighthouse and likes marmalade better than is strictly defensible.

At bedtime, Jacob asked, “Do we live here forever?”

“Forever is a big word,” I said. “But we live here now. And we live together.” He nodded, satisfied with the smaller truth.

The next day was a montage of paperwork and meetings and the kind of logistics that keep grief from becoming a vocation. Michaela filed the order; a judge signed it with a crispness that suggested she’d sharpened her pen on worse stories. The school noted Margaret’s name with a thick red line through it; the pediatrician updated the chart and added a star. Detective Rios called to say the hotel footage showed a woman who looked like my mother speaking to the head server and handing over a slip of paper. The chef denied direct knowledge; the server remembered “a grandmother with authority.” The memo’s ink matched pens in the hotel supply closet. No one at the kitchen level had wanted this; a roomful of people had let it slide because old ladies with pearl earrings are an institution.

“Any chance your mother will talk?” Rios asked.

“Talk? Sure,” I said. “Confess? No.”

He sighed. “We’ll see where the DA wants to take it. Paper trails help. Judges like paper. Juries like videos. Everyone hates shrimp now.”

That afternoon, Margaret called from a number I didn’t recognize. Her voice did that thing voices do when they’re trying to be twenty again—bright and breathless. “Emily, darling. You’re safe? Jacob is safe? Good. Listen—”

I hung up. Then I blocked the number. Then I wrote a text to Sophia: If Mom contacts you, tell her all communication goes through my lawyer. And please don’t tell me if she sends you apologies. I won’t read them.

I understand, she replied. I’m so sorry. Three dots. I loved you before this. I love you now. That doesn’t fix anything. It just is.

It helps, I wrote. It did, in that small way sturdy things help—you don’t fall through the floor.

Days passed. Not a lot of them, but enough to learn that time is still a concept and not a prank. The Grand Harbor sent a letter promising cooperation and a gift certificate for a future stay I planned to use never. The news cycle sniffed around the edges, but weddings are noisy and scandals plentiful, and the story didn’t find purchase beyond our corner of the world. I returned to the office and did adult arithmetic for other people’s dreams. I made lunches and miniature moral compasses for the person I loved most. We learned a new bus driver’s name. I bought a new lock.

One evening, a week after the memo, I found a padded envelope in my mailbox that looked like it had come through a storm. The handwriting on the label was familiar. I carried it upstairs and stared at it on the counter the way you stare at a spider on the ceiling: polite dread.

Inside were three letters. All from Margaret. All unopened. Their dates covered three days. The first was likely apology. The second likely rationalization. The third—who knows. I didn’t open them. I slid them into a drawer next to the instruction manuals for appliances and the insurance policy we could now recite by heart.

We ate dinner—grilled cheese, tomato soup, a salad to appease the gods of adult choices. Jacob put his red car on the table’s edge and looked at me with a seriousness that made me feel twenty feet tall and tender as tissue.

“Are we happy?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, surprising myself with the speed of it. “We’re scared and tired and a little mad, but we’re happy, too.”

“Okay,” he said. He knocked the car off the table and leaned to retrieve it, then popped back up triumphant. “Still here,” he announced to the room.

“Still here,” I echoed, to him, to the table, to the universe. It felt like a promise and a vow and a thesis statement.

That night, after Jacob fell asleep and the building settled into its chorus, I opened my laptop and pulled up a map of the United States like a person shopping for a new ending. I traced the line west with my finger. Portland. I’d been once, years ago, on a trip where Michael and I ate donuts that defied geometry and stood in a bookstore so large it felt like a city with its own zoning laws. The thought rose and settled: a new place, less history to trip over, more sky you can see without craning.

“Maybe,” I told the dark. It’s a word I’ve come to respect. It’s not evasive if you use it like a bridge.

In the morning, I walked Jacob to school and met the new crossing guard, a woman who glowed with the kind of competence that makes you want to hand her your most breakable things. I told her our names. She wrote them on a clipboard with a purple pen that dot-ted its i’s with hearts. It would have annoyed me last month. Today it felt like oxygen.

On the way back, my phone buzzed. Two headlines, forwarded by Sophia: Local Investment Firm Accused of Fraud and, beneath it, as if a follow-up and a punchline had a child, Harrison Named in Civil Suit. I texted back: I’m sorry. And also I’m not, because this way you know the truth. She wrote: I know. I’m filing today.

I put my phone away and watched a squirrel attempt the high-wire act of a telephone line. He made it, wobbly but committed. Momentum is a kind of courage.

That afternoon, Detective Rios called again. “We’ve referred it to the DA,” he said. “They’ll look at attempted something. There’s enough for restraining orders to stick like duct tape. If she violates, call. Don’t hesitate.”

“I won’t,” I said. “Detective? Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me,” he said. “Go make pancakes.”

After bedtime, I opened the drawer with the padded envelope and took the letters out again. I stacked them like a small skyline on the table, then slid them back in. Not reading was its own kind of reading. Sometimes silence is the only punctuation that tells the truth.

Before I turned in, I took the red car from the counter and set it on the windowsill, nose aimed west. “We’re looking,” I told it. “Not running. Looking.”

The car, being a car and plastic, did not respond. But in the dark glass, my reflection looked like a woman who had survived a wedding and still believed in vows.

Tomorrow I would call a recruiter in Oregon. Tomorrow I would tell Michaela to start the paperwork that untangles geography from ghosts. Tomorrow I would send Sophia the name of a therapist who specializes in brides who discover they married a spreadsheet.

Tonight, I lay down beside the door to Jacob’s room again. It was less for security and more for tradition now; sometimes we choose rituals not for belief but for comfort. Through the wood, I could hear him turn once, then sigh, then settle. Our building sighed back. The night did its night thing.

We slept.

Part Three: Breakage and Boundaries

The courthouse tried to look like justice lived there. Flags, marble, a security line that flirted with self-importance. The vending machine favored snacks with names like “Mega Crunch” and “Extreme Cheddar,” which felt like an indictment of both sodium and subtlety. I signed in, collected my visitor badge, and followed signs to Family Court with a knot in my stomach and a stack of documents that had learned how to glare.

The emergency restraining order Michaela filed had the personality of duct tape—useful, immediate, not meant to be pretty. Today’s hearing would decide whether duct tape became scaffolding. Michaela met me outside the courtroom, blazer crisp, hair in a bun sharp enough to slice arguments. “We’ll keep this simple,” she said. “Facts, not feelings. You don’t have to be a saint. You just have to be safe.”

Sophia was already inside, hands wrapped around a paper cup like warmth came with refills. She stood when she saw me, looking unsure whether to hug. I spared us the awkwardness and nodded. “Thank you for being here.”

“I belong in this mess,” she said. “At least until I can help pick it up.”

Detective Rios slid in behind us with a nod that said he knew where the good coffee wasn’t. When the clerk called the case, my mother stood at the opposite table, smaller than I remembered and somehow louder. Her pearls were present, battle-ready. She did not look at me.

The judge—a woman with the aura of someone who’s seen every version of today—reviewed our files as if paper had tone and mine was in key. Michaela began, not with theatrics but with timestamps: the memo, the hotel’s camera footage showing Margaret handing a slip to the head server and pointing toward the seating chart, my son’s medical records documenting an anaphylactic event two years prior, the pediatrician’s letter explaining Jacob’s allergy in the plainest English medicine ever managed.

“Ms. Chambers is not seeking to shame a relative,” Michaela said, voice clean. “She is seeking to protect a five-year-old and herself from a pattern of calculated disregard.”

My mother’s lawyer stood, slick as a new phone case. “Your Honor, this was an unfortunate misunderstanding. My client never intended harm. In fact, she has been instrumental in her grandson’s care since birth. She was worried about her daughter’s recent decline—weight loss, insomnia—and, regrettably, made mistakes while under considerable stress from another daughter’s wedding.”

The judge looked up, gaze so level it could check bubbles in a carpenter’s tool. “She wrote ‘don’t worry about allergies’ on a note requesting shrimp.”

The lawyer opened his hands, a pantomime of innocence. “She meant the kitchen would already be aware—”

Michaela tapped the plastic sleeve with a fingernail. “Then why instruct them at all?”

Margaret finally spoke. “Because no one listens unless a mother insists.” Her voice trembled, and for a second I saw the teacher who had once taught half a school to read and the mother who had once taught me to cross the street. “I was trying to help. I have always tried to help.”

“By adding a lethal allergen to your grandson’s plate?” the judge asked, not cruelly—only as someone who doesn’t permit the English language to be bullied. “Ms. Chambers, do you fear for your safety and your son’s safety if the respondent is permitted contact?”

“Yes,” I said. The word arrived steady, bowl-shaped, holding everything it needed to without spilling. “Because she believes she’s right.”

The judge signed. One-year order, no contact, no proximity to home, school, or my office. Violations would invite handcuffs to the party. “Family is sacred,” she said, pen pausing just long enough to be a lesson. “Which is exactly why the law protects people from family.”

Outside, in the echoing hallway, Michaela exhaled like a pressure valve. “That’s a good order. Make copies. Keep one in your purse, one in the glove box, one taped to the inside of your skull.”

Sophia stepped closer. “I… I didn’t testify,” she said, apology tucked into the folds of her voice. “I didn’t know if it would help or hurt.”

“It helps that you’re not defending it,” I said. “Sometimes silence is the most articulate thing we own.”

Detective Rios handed me his card for the hundredth time. “If she shows up, call,” he said. “We’ll play bad cop. It’s my best sport.”

We went our separate ways like a band breaking up on amicable terms. I walked home through air that had decided to be November early. The trees along the river were doing their slow striptease, shrugging off color. Boston does seasons like a stage actor—big, declamatory, shameless about costume changes. I breathed in cold, and it felt like honesty.

If life were a tidy paragraph, that would have been the end of my mother’s appearances. Life is a footnote factory. Three days later, she left a bouquet outside my door with a note in the looped handwriting that had once written permission slips and spelling words.

I’m sorry. Please let me see Jacob. I’ll explain everything. Love, Mom.

I kept the flowers; I tossed the note. Then I texted Sophia: Order says no contact. She left flowers. Tell her to stop. Next time I call Rios.

I will, she wrote. I’m so sorry, Em. I’m staying firm. You were right about David. The financial investigator said “pattern.” I filed today.

Good, I typed, and then, because honesty had become my hobby, I’m proud of you.

That night, Jacob and I ate spaghetti and watched a documentary about whales that made him whisper “whoa” every six minutes. He fell asleep mid-whoa, mouth open, one hand on the red car like it might swim away. I stood at the window and considered the geometry of leaving. The map glowed on my phone like a dare. Portland’s dot looked friendly.

Liv knocked with brownies and gossip. “I can feel the vibes through the drywall,” she said, pushing the pan onto my hands. “How are you holding up?”

“Legally upright,” I said. “Emotionally… still learning to walk.”

She nodded and plopped onto my couch. “I’m on call tomorrow. If you need a ride to anywhere but a wedding, text me.”

We ate brownies with forks because plates are just a suggestion, and she left me with three very specific hugs that said nurse, neighbor, friend.

The next morning, I drove to the cemetery with Jacob, a bouquet of grocery-store sunflowers in the passenger seat and a nervous sermon in my head. Michael’s grave is simple—name, dates, one engraved line that says Builder of beautiful things. I don’t believe in haunting; I do believe in talking to the people we miss. I do it the way I fold laundry—tenderly, badly, with love and uneven corners.

Jacob stood with me, red car in his pocket. “Hi, Daddy,” he said, voice small and perfectly sufficient. “We’re moving to where it rains. Mommy says it’s a fresh start. I like fresh starts.” He set the red car on the headstone for a moment like a pit stop, then took it back and put it to work patrolling the base of the marker for rogue ants.

I told Michael the rest. The memo, the order, the way our son builds cities now, the way my mother’s choices have rewired my definition of the word family. I told him I was scared to leave and scared to stay and that fear had become an unreliable narrator. I told him I missed his laugh in the morning, the one that turned burnt pancakes into a festival.

“I’m going to keep us safe,” I said finally. “And I’m going to keep us happy, which is related but not identical.”

Jacob looked up. “Do dead people read letters?”

“Not with eyes,” I said. “But I think they hear the parts that matter.”

We left the sunflowers. We took the car. That’s the thing about rituals—if you perform them sincerely, they rearrange something inside whether or not they rearrange anything outside.

Packing started as disaster and matured into slapstick. Liv labeled boxes with painter’s tape (“KITCHEN—NO, REALLY THIS TIME” and “LINENS & LINEN-ADJACENT”) while Jacob colored every box with a red streak so he’d “know where our racing stripe went.” I sold furniture to strangers from a site that doubles as a sociological study in how many emojis people consider persuasive. I booked a mover who assured me that crossing a continent is nothing more than a collection of right turns and receipts.

My boss, Diane, listened to “Portland” and said “remote,” then “trial period,” then “we’ll figure it out” in that order. The firm could survive me on Zoom; I could survive myself in Oregon. For once, logistics and longing shook hands.

Michaela, practical as pockets, sent over a checklist that belonged in emergency-preparedness pamphlets: school records, medical records, prescriptions, contact lists, Jacob’s EpiPens in triplicate, the order printed and laminated, a photo of Margaret (current) and a list of approved pickup people for Jacob’s new school.

“Put your safety plan in your phone under ICE,” she said. “In Case of Emergency. Old nurses’ trick.”

“Liv would approve,” I said.

“She already texted me three medical acronyms I had to Google,” Michaela said. “You have an excellent cabinet.”

“Village,” I said. “But yes.”

The last week in Boston tried out for the role of worst week and narrowly lost to the one with the memo. Margaret didn’t violate the order again, but her absence had weight. It pressed against the edges of each day in a way I couldn’t unpack without getting a splinter.

Sophia came by once more to say goodbye. She brought Jacob a book about a robot who learns to love ducks, and me a bag of coffee so Portland couldn’t accuse me of arriving unprepared.

“I found an apartment,” she said. “Month-to-month. I told Mom she can’t have a key. I told her I’m not her plan. I told her she needed help I can’t give.”

“How did she take it?” I asked.

“Like a woman who’s always been listened to,” she said. “But she didn’t argue like usual. It was… quieter.”

I thought about quieter and wondered if guilt has a hush setting.

“I read an article,” Sophia added carefully. “About David. He’s being sued. Fraud. The comments are a Greek chorus.”

“Good,” I said, with a small mean satisfaction I refused to file under spiritual growth. “You deserve better than a man who thinks marriage is a liquidity event.”

She laughed, genuinely, for the first time in weeks. “Promise me one thing?”

“If it’s not shrimp-related,” I said.

“Don’t disappear,” she said. “Please. Send me a photo when Jacob loses his next tooth. Or when you find a coffee shop you like. Or when it rains. Which I hear is hourly.”

“You can visit when it’s not raining,” I said.

“So, never,” she said, and we both smiled in a way that meant we were trying.

She hugged Jacob and he tolerated it with the stoicism of a small mayor accepting a hard day’s constituents. At the door, she turned back. “Em? I know Mom is… what she is. If she ever gets the kind of help that helps, I’ll tell you. I won’t ask you to fix it. I’ll just tell you.”

“Okay,” I said. It felt like a treaty signed by people who’d read the fine print.

We didn’t drive to Oregon. I romanticized the idea for six minutes—roadside diners, national parks, the red car performing a nation-spanning tour—and then remembered I had a five-year-old and a spine. We flew. Movers took the boxes; Liv took photos of the apartment after the final sweep so I could mail the landlord proof that “normal wear and tear” is not a synonym for “gouged hardwood.”

At Logan, TSA eyed the EpiPens, nodded, eyed the red car, complimented it. Jacob held my hand, held the car, held his breath at takeoff until I said, “We breathe now.” He exhaled like a balloon visiting earth again.

On the plane, he asked, “Do the clouds feel?” and then fell asleep with his cheek on my arm and the red car tucked between our seats like a co-pilot with union rules. I watched the grid of the country scroll beneath us—fields and rivers and shapes that architects and cartographers pretend are predictable. Somewhere over the middle, I allowed myself to think the dangerous thought: maybe.

We landed in rain, because of course we did. Portland welcomed us with moss and kindness. The rental car was neither red nor glamorous, which suited me like a sensible shoe. Our short-term rental had the personality of an Airbnb trying too hard—succulents, framed quotes about coffee, a couch that squeaked at moral dilemmas. It also had a lock that turned smoothly and a window that looked out on a tree I did not know the name of yet.

The next morning, the sky wore a gray sweater and we wore newness. I made oatmeal badly and coffee decently; Jacob declared both “fine” with the breezy magnanimity of a person whose standards are elastic when the day is shiny.

We walked the neighborhood. People said hello the way New Englanders reserve for natural disasters and dogs. We found a park where the slides ended not in rubber chips but in actual dirt, which felt like a policy decision and a metaphor. Jacob watched a group of kids build a dam in the sandbox with the solemn urgency of engineers on a deadline. A girl in a yellow raincoat approached him. “Wanna help us stop the river?”

He looked at me. I nodded. He looked at his car. He parked it on a bench. Then he went to work.

I sat on a wet bench and a woman with a stroller sat near me like we’d planned it. “We moved here last month,” she said. “From Phoenix.”

“Boston,” I said.

She grimaced in sympathy. “I miss my hair not frizzing,” she said. “But the people are disgustingly nice.”

We chatted about schools and pediatricians and bakeries that put salt on cookies in an effort to ruin you for all other cookies. She introduced herself as Mariah and her baby as Sasha, who wore a hat equal in circumference to her opinions. “If you need anything,” Mariah said, “text me. In this town, we swap tools and childcare like recipes.”

“I have recipes,” I said. “None of them fancy. All of them edible.”

“Edible outranks fancy,” she said. We exchanged numbers and the tentative promises of people who suspect they’ll mean it.

On the way home, Jacob tugged my sleeve. “Mommy, this river won’t stop. But we did good.”

“Some rivers don’t stop,” I said. “Doing good counts anyway.” He considered this, nodded as if adjusting schematics, and asked if we could get hot chocolate because engineers require fuel.

We found a café with a chalkboard that insisted someone named Maddy makes the best scones in the county and a barista who called everyone “friend.” I sipped coffee and watched Jacob stand on his chair to peer at a shelf of board games like a curator evaluating a traveling exhibit. The chalkboard also advertised open mic poetry and a lost glove. The glove drawing had more personality than some people’s headshots.

My phone buzzed. A headline from the Boston Globe: Local Investment Advisor Sued in Fraud Case; Sources Confirm Multiple Plaintiffs. Below it, a smaller piece: Former Teacher Margaret K. Chambers Resigns from Volunteer Board. The photo wasn’t flattering; the facts were not either. The feeling that rose surprised me. Not victory. Not schadenfreude. Something closer to relief that the floor was no longer arguing with gravity.

I closed the article and looked at my son, pink-mouthed from hot chocolate, alive and ordinary and miraculous. “Hey,” I said. “We’re here.”

“We’re here,” he agreed, as if he had been waiting for the memo.

That evening, after boxes labeled KITCHEN—NO, REALLY THIS TIME surrendered two pots and a spatula, we made scrambled eggs and toast and declared it gourmet because the plates were clean and the table was ours. The rain drummed like applause. We drew up a list of things to learn—bus routes, tree names, how Portlanders tell directions without using Dunkin’ as a cardinal point.

Jacob fell asleep fast, red car parked under his pillow the way knights used to sleep with swords. I stood at the window and looked at the new street—porch lights, bicycles, a cat who owned several houses. Across the way, someone practiced scales on a trumpet with the pleasing sincerity of a beginner. The note wobbled, then steadied. The second try was better.

My phone pinged once more. A text from Sophia: I signed today. It’s done. I start a new job next week. How’s the rain?

Ambitious, I wrote. How’s the freedom?

Also ambitious, she replied. After a pause: Give Jacob a kiss from his aunt who is learning what family means the hard way.

I will, I typed. I’m learning the easy way—by staying only with the people who keep us safe.

I put the phone face down. I turned off the last light. In the quiet, I said goodnight to a city that didn’t know us yet and to a life that was beginning anyway. I thought of the memo that had tried to end us and of the order that had said “no farther” to danger and of the airplane that had agreed to become a bridge because we asked it to and gave it money.

And I thought, briefly and without guilt: Margaret made her choices. I’m making mine.

Jacob stirred, sighed, returned to his small stormless sleep. I slid the red car from under his pillow just enough to see it gleam in the streetlight, then slid it back. He didn’t wake. The car didn’t mind. I stood there until the trumpet next door found its note again.

We slept in our new city, in our new home, with our old hearts and their red racing stripe pointed forward.

Part Four: The Geography of Safety

Portland liked to introduce itself by clearing its throat. Every morning, the sky coughed up a mist, the kind that doesn’t bother with drops so much as a general policy statement about moisture. I learned the rhythms fast: coat on the hook, towel by the door, coffee first, then more coffee. Jacob learned fast too. He began rating puddles on a ten-point scale and lobbying city council (me) for a rubber-boot budget increase.

The apartment settled around us with the soft thumps of new habits. The couch squeaked its opinions; the kitchen admitted it wasn’t fancy but would show up. On Monday mornings, I logged into work early, brightness turned up too high so Boston faces wouldn’t accuse me of glowing from the wrong time zone. On Tuesday afternoons, Mariah texted “Park?” and I texted back a photo of a red car on a slide, which counted as consent. On Wednesdays, Jacob and I tried a new bakery and pretended we had the authority to crown a croissant king.

It was, against my better instincts, nice.

The school did its part. The principal met us with a smile that could serve as a seatbelt. The nurse took Jacob’s medication plan like a mission briefing and asked three extra questions, which is the exact number of questions that instill confidence without turning you into an anecdote. His teacher, Ms. Powell, had a classroom that looked like a small democracy—labels at kid eye level, a reading corner that could fix the economy, and a “class promises” poster written in first-grade scrawl: We listen. We help. We don’t yuck someone’s yum. We added: We don’t make yums that make people die, with a smiley face drawn by the nurse for tone.

Ms. Powell knelt to Jacob’s level. “Tell me about your favorite things,” she said.

“Cars,” Jacob said. “Red ones.”

“Same,” she said solemnly, and they were bonded for life.

I folded myself into the school’s PTA-adjacent group, which in Portland is less Bake Sale Warriors and more Civic-Minded People Who Compost. The president, Jules, could organize thirty volunteers by the end of a sentence. He assigned me to “signage and allergy labels” for the upcoming fall festival, where the school would churn cider with the kind of optimism only elementary educators possess.

“I take labels seriously,” I told him.

“Bless you,” he said, and handed me a stack of neon markers and the authority to shout at anyone with unlabeled hummus.

The week before the festival was domestic and suspiciously normal. We sipped cocoa before school and made soup after. We collected leaves that insisted they were art. One night, Jacob announced the tree outside our window was named Harris. “Like Harrison?” I asked, unthinking, and he said, “No, like Harris. He’s his own man.” Fair enough.

I started running again. Not for speed—the body keeps receipts—but for oxygen and the thrill of being a person moving toward something that wasn’t an alarm. I ran past bike shops that doubled as coffee shops that tripled as social clubs, past murals so earnest they made me tear up, past a library that didn’t whisper because it was too full of children who hadn’t learned to be quiet about wanting.

When I got home, Liv texted from Boston: New grad nurse started on nights. Already calling coffee an IV. Also, your old super says your apartment is “a paragon of tenant behavior.” I told him to embroider it on a pillow.

Frame it, I replied, and sent a photo of Harris the tree doing his best impression of green thunder.

Then the festival arrived and decided to audition for a metaphor.

It started charming. Parent volunteers erected booths with a competence that made me consider advocating to let them run government. Jules’s signage—my signage—looked like a beacon for accountability: Contains Nuts, Gluten-Free, Dairy, Vegan, No, Really Gluten-Free, and my personal favorite, which I wrote in block letters large enough to shame a billboard: SHELLFISH-FREE ZONE.

By noon, the place smelled like apples flirting with cinnamon. Kids ran with the precise level of chaos that suggests angels moonlighting as crossing guards. Jacob stuck to Ms. Powell like an apprentice to a magician, and his red car took a sabbatical in my pocket to prevent it from becoming somebody’s prize.

It went wrong in the way things go wrong when good intentions take a bathroom break. A kindly grandpa with a folding table and a lifetime membership card to “I’ve always brought this to potlucks” set down two trays of steaming dumplings with a handwritten label: Prawn & Pork, made with love. He beamed. He meant well. He also set the tray right next to a sign that said SHELLFISH-FREE ZONE because life likes dramatic irony more than any other genre.

I didn’t see it first. Ms. Powell did. She moved with that quiet speed teachers have, the kind that keeps crisis from knowing it’s been spotted. She put her hand on the tray, smiled at grandpa, and said, “Let’s give these an honored place over there, in the ‘grownups only’ section, and put a new sign on them so our friends with allergies stay safe.” He nodded, slightly bewildered but unoffended. She retrieved me with a look and three syllables: “Help? Now.”

We relocated the dumplings. I re-labeled with the kind of caution that would make a bomb squad proud. Then—because systems fail precisely where you think they won’t—someone nudged the prawn tray into the orbit of the pork tray. A hungry kid grabbed indiscriminately. A tiny hand. A familiar hoodie.

Jacob.

Ms. Powell saw it at the same time I did. “Hey, bud!” she called, her voice perfectly normal, the way you address a kid about to pet a porcupine. “Trade you!” She reached him in three steps, put a napkin into his hand like a magic trick, and swapped the offending dumpling for an apple slice.

Jacob blinked, confused, then shrugged and bit the apple. Ms. Powell leaned toward me. “I didn’t want to yell ‘SHELLFISH’ across the schoolyard,” she murmured. “How’s your heart rate?”

“Leaving my body,” I said. We laughed, because the other option was inconvenient in public.

Ms. Powell squeezed my shoulder. “I’ve got your kid,” she said, simple as a promise. She turned and bee-lined to Jules, who was already ushering the prawn tray further away with the diplomacy of a man who has moved cross-country three times and knows how to carry breakable things.

I found Mariah by the cider press, handed her the red car, and told her to keep it safe as if she hadn’t kept bigger things. She handed me a cup and said, “Drink. You just saw the bad version of a parallel universe. We’re living in the good one.”

I drank. It tasted like an orchard getting a standing ovation.

Word of the near-miss spread along the volunteer grapevine with the speed of gossip that matters. By 2 p.m., “allergy captains” were stationed like lifeguards. Someone printed more labels. The kindly grandpa got deputized to tell his prawn origin story in the grownups-only zone with the resigned air of a man who has discovered bureaucracy in a place where he expected only joy.

At cleanup, Jules gave me a fist bump. “That was… not ideal,” he said. “But the fix was fast.”

“The fix was Ms. Powell,” I said. “Put her on the city payroll.”

“We’re working on it,” he said, and I couldn’t tell if he was joking.

That night, when Jacob was asleep, I sat at the kitchen table and trembled. It wasn’t delayed fear; it was delayed physics. The energy my body had spent not sprinting across the playground at a hundred decibels needed somewhere to go. I called Michaela and told her the story.

“You did everything right,” she said. “So did your teacher. So did the community. Systems aren’t foolproof. That’s why we build people into them.”

“I thought moving would cure everything,” I said, hating how naive that sounded.

“Moving cures some things,” she said. “For the rest, there’s vigilance and friends and signage and the knowledge that you can do hard things without letting them colonize your joy.”

“Is that from a poster?” I asked.

“It is now,” she said.

Two days later, Jules emailed asking if I would speak for five minutes at the next PTA meeting about allergy inclusion and safety. “You’re a good communicator,” he wrote. “Also, your signs slapped.”

I wrote a talk that was short, specific, and laced with enough humor to keep it from turning into a funeral. I opened with the obvious: “If a five-year-old is about to put a prawn in his mouth, act like a magician, not a fire alarm.” I explained cross-contamination in terms that would not trigger an existential crisis. I provided a cheat sheet that included the sentence, If the label contains ‘may contain,’ assume ‘will.’ I ended with: “Safety isn’t just rules; it’s culture. Culture is what we do without thinking. Let’s make kindness our reflex and labels our love language.”

A mom stood to say she’d cried in the car after the festival because she realized she’d never factored someone else’s kid into her cooking. A dad volunteered to build a dedicated Contains Shellfish table with caution tape and a bell. Jules proposed standardizing potluck labels district-wide. We voted by applause. It was the most productive five minutes of civic life I’d had since voting for a library bond.

After the meeting, Ms. Powell handed me a note written in Jacob’s careful grippy first-grade. Dear Mommy, I did not eat the wrong thing. Love, Jacob. Underneath, he’d drawn a red car racing away from a tiny shrimp with fangs. The shrimp was crying. I kept the note in my wallet behind my driver’s license, because some documentation actually improves your life.

Sophia arrived the following weekend with a duffel bag and a face that had learned new math. She took one look at Harris the tree and announced she approved of our neighborhood. Jacob introduced her to the slide and to his ranking system for puddles. She introduced us to the concept of “divorce cookies,” which are regular cookies with extra chocolate chips and less shame.

We walked by the river. She told me about the annulment being approved, about the way her lawyer had used the phrase “entered under false pretenses” like it was a surgical instrument. David had been served with a suit and a subpoena and a bad week. She had started temping at a nonprofit that teaches girls to code, where her job was mostly making sure the snack budget was sane and the mentorships were real.

“And Mom?” I asked, because there’s always a second shoe, and sometimes it’s not a shoe.

“Therapy,” she said. “Not for the first time, but for the first time like she means it. She sent me letters for you. I didn’t bring them.” She hesitated. “One had a copy of a text from David. Threats, not physical but financial. I think she thought it made her look like a victim. It just made me look at my phone bill and wonder how long she’s been talking to people who don’t deserve her voice.”

We were quiet long enough to hear a heron declare its opinion on fish. “If she ever gets better,” Sophia said, “I’ll tell you. Not to fix it. Just so the story you have in your head includes the chapters that aren’t horror.”

“Okay,” I said. “I can live with that.”

We stopped at the café with the chalkboard that had strong feelings about scones. The barista remembered me as “Allergy Label Lady” and gave me a free refill. “Hero discount,” he said. “Also, your kid high-fived me last week. That’s priceless.”

Sophia stared at my face. “You’re softer,” she said.

“It’s the humidity,” I said.

“It’s not,” she said, and we both decided to let the compliment stand without cross-examination.

That night, after Jacob conquered his bath like a brave nautical captain and fell asleep with a towel-cape on his shoulders, Sophia and I sat on the floor and sorted through the family photos Aunt Dorothy had mailed, because Dorothy believes in the USPS and drama. We made three piles: Keep, Digitize, Exorcise. “Exorcise” was mostly duplicates and a handful of haunted shots where one of us is crying in a Halloween costume. “Digitize” was the bulk. “Keep” was Dad’s hands steadying the back of a wobbling bike and Michael laughing into a wind that wasn’t in frame.

I held up a photo of Margaret reading to both of us on a couch I can still feel if I close my eyes. “She was a good mother,” I said, which is true and also incomplete.

“She still might be,” Sophia said. “To herself. Someday.”

We went to bed too late for women with alarm clocks, but early for women who’d once believed family was a thing you inherit rather than a thing you build.

I woke at 3:17 a.m. to rain and to a feeling like a page turning. I made tea and stood at the window and watched Harris shake off the weather. My phone buzzed. Liv: Night shift. Guy swallowed a bee. He’s okay. Statistically, life is absurd and survivable. How are you?

Absurd and survivable, I wrote back.

When morning arrived, Jacob announced we needed a “home club” and designed membership cards out of index cards and crayon. He made one for me, one for him, one for Harris the tree (honorary), one for Sophia (guest pass), and, after a long and serious pause, one for Grandma—someday, which he placed in a drawer. “Just in case,” he said. “We can decide later.”

“Later” is a kind of grace that children invent and adults forget.

We spent Sunday afternoon building a blanket fort so extreme it achieved mezzanine status. We strung up battery lights from a box labeled DECOR—OMG WHO AM I, and the effect was less Pinterest and more fire hazard, but it made Jacob gasp like the first time he saw fireworks. He crawled inside and declared it a “no-prawn zone” and also a “laughing only zone.” I crawled in after him and declared it ours.

He handed me a wooden spoon like a scepter. “What should our motto be?” he asked.

I thought about everything—the memo and the courtroom and the plane and the puddles and Ms. Powell’s hands and Jules’s labels and Mariah’s number and Liv’s brownies and the barista’s hero discount and Sophia’s divorce cookies and Harris standing there doing tree things in a world that doesn’t always reward trees.

“Still here,” I said. “Still here and moving.”

He nodded, solemn as a mayor. “And no shrimp.”

“And no shrimp,” I agreed.

We lay on our backs under the battery-star ceiling and listened to the rain talk to the roof. It sounded like applause again, or maybe like prayers. Either way, it was decent company.

Part Five: Still Here and Moving

A year is a strange animal. It’s long enough to teach you a new alphabet and short enough to feel like a single sentence you forgot to punctuate. On the anniversary of the night we left the Grand Harbor, Portland threw us a sky so clean it looked ironed. Harris the tree went dramatic in gold, Jacob insisted the day required pancakes with chocolate chips “for bravery,” and I burned the first one on purpose because tradition is a rope you can hold when the ground tries a new trick.

“Is this a special day?” Jacob asked, chin sticky, eyes conspiratorial.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s the day we decided to steer ourselves.”

He nodded, because steering is a concept that makes sense when you own a red car.

We celebrated in the ways that have become our family’s version of fireworks: a walk along the river until our cheeks pinked, a stop at the café where the chalkboard had updated its manifesto to Maddy’s Scones Remain Supreme, and a detour through the library big enough to adopt lost afternoon hours. In the children’s section, Ms. Powell materialized from the stacks with a wave like a cameo. “Our favorite engineer,” she said to Jacob. “Are you still rating puddles?” He solemnly produced a new notebook labeled PUDDLES & OTHER IMPORTANT DATA. “Excellent,” she said. “Peer review at recess.”

Portland had become muscle memory. I had clients who thought of me as the accountant with the precise emails and the excellent snack recommendations. Mariah could read my texts in weather terms: Need extra eyes on school logistics? (drizzle); Having a day? (downpour); Come over, I made too much soup (rainbow). Jules had turned my five-minute allergy talk into a district policy and occasionally sent me photos of signage that made me mist up like a person moved by fonts. Liv still worked night shifts in Boston and texted dispatches from the absurd: Patient swallowed a chess pawn because “I wanted to feel like a queen.” She’s okay.

Sophia called more now that we lived farther away. Proximity had never been our love language; attention was. She’d left temp work for a full-time job at the nonprofit, discovered she was meaner about lunch budgets than she’d imagined, and started a weekly dinner with two women from her building who were teaching her to cook rice without consulting the back of the bag. “Turns out when I’m not busy being a bride, I’m interesting,” she said once, half-joking, wholly relieved.

As for Margaret, the restraining order expired and I renewed it without fanfare. The court clerk’s stamp was indifferent and merciful. Through Sophia—and only through Sophia—I heard that our mother had stuck with therapy past the chapter where you can still blame your children for your choices. She’d left three more letters with Michaela, “in the file,” as if apology were a document that could be notarized. I didn’t open them. Some bridges you don’t burn. You just stop checking if they’re load-bearing.

Two weeks after our anniversary day, the DA’s office finally sent a letter that said, in language so dry it chapped lips, that they would not pursue criminal charges “at this time.” Insufficient evidence for an attempt; enough for a story no one wanted to tell a jury. I read the letter once and put it in the drawer with the others. Justice had dropped its gavel in smaller ways: the order, the policy, the move, the absence.

That night, after Jacob fell asleep with his red car tucked beneath his pillow like the small knight he believes he is, I wrote my own memo—the first I’d written in a year that didn’t include the word “Exhibit” or “see attached.” I began with a date and a vow, because weddings don’t own vows.

To Future Us:

I promise pancakes and burnt first tries. I promise to teach you how to braid your shoes and your courage. I promise to pick towns with more trees than grudges. I promise to say “no shrimp” even when everyone else says “just a bite.” I promise to keep our door locked, our minds open, our family small enough to fit under a blanket fort and big enough to fit everyone who keeps us safe.

Still here. Still moving.

—Mom

I taped it inside the kitchen cabinet with the mugs, so we’d read it every morning before we caffeinated our hope. It looked right there, next to the chipped cup Michael brought home from a diner in Vermont, the one that says EAT GOOD FOOD in a font that has never heard of minimalism.

A week later, we drove to the coast with a council-approved playlist (one song about whales, one about trucks, one about how you can go your own way, courtesy of my old heart). Oregon seems like a magician’s pocket sometimes—the way it produces forest, then fog, then ocean in the span of one sentence. Jacob named the waves (“This one is Fred, and Fred is ambitious”), and we ate grilled cheese at a diner whose ketchup bottles could tell a better history than most textbooks.

Back in the city, Mariah roped me into a Saturday project that was either community service or the pilot for a sitcom: painting a mural on the side of the school gym. Jules found us a grant; Ms. Powell wrangled kids with an iron-laced-with-glitter fist; a local artist wielded cans and kindness. The mural began as a river and ended as a map: bridges, trees, three small outlined figures holding hands, and a red streak racing toward the edge. When we were done, Jacob stepped back, hand in his pocket, and nodded like a foreman. “Needs a sign,” he said.

“What should it say?” I asked.

He grinned. “Still here.”

We painted the words in block letters so solid they looked like you could climb them.

That afternoon, a cloudburst tried to steal our thunder, but the paint dried under a borrowed tarp and the children dried under squeals. I stood with Ms. Powell, sleeves rolled, hair damp, watching a gaggle of first-graders convert a puddle into a municipal concern. “You have a sturdy kid,” she said.

“He built his core the hard way,” I said.

“Most good structures do,” she said.

We watched in companionable silence while Harris the tree, visible over the fence like a witness who refuses to leave town, swayed and unearthed a shaft of sun.

Then Jacob lost his first tooth. He came tearing out of the bathroom with the speed of emergency and the grin of a victory parade. “It popped!” he announced, bloody, thrilled, holding the small white comma that had once been part of a sentence he learned to speak.

We did all the rituals—cup of water, tiny envelope, photo with a smile so gap-toothed it could charm a miser. I sent the photo to Sophia with the caption: Dental milestone achieved. Tooth Fairy union has been notified. She replied with a string of tooth emojis and the keyboard-version of a shriek.

At 3 a.m., I woke with the clarity of a person who has remembered both a science fair and her taxes. Tooth. Pillow. No cash. I scoured the apartment for legal tender and found three singles and a movie ticket stub that would impress no one. I wrote a note instead, on Tooth Fairy stationery I improvised out of a sticky note and a gel pen:

Dear Jacob,

Excellent craftsmanship on that tooth. Please accept this money and a voucher for one extra bedtime story. Keep brushing. The Fairy Guild loves a hardworking jaw.

—TF

In the morning, Jacob read the note aloud with the seriousness of a policy analyst. “Voucher,” he said, pleased by the sound of the word. He tucked the bill into his piggy bank and the note into his PUDDLES & OTHER IMPORTANT DATA notebook, which felt like a promotion.

He looked up at me. “Mommy, what are guilds?”

“Unions for magical creatures,” I said, and he nodded, satisfied we lived in a just universe.

That afternoon, for reasons only the universe understands, a box arrived from Aunt Dorothy containing a hand-knit scarf the color of certainty and a passive-aggressive tea towel that said KITCHENS ARE FOR COOKING, NOT FOR DRAMA. “Debatable,” I told the towel, and used it anyway.