The reservation at Meridian was for 7:00—prime time by any standard. Every table was full. The dining room buzzed with the sound I had come to recognize as the pulse of a successful night: forks chiming against china, low laughs folding under the hum of conversation, the flash of a server’s tray moving past like a well-timed comet. From the kitchen, a steady percussion—the clap of pans, the quick hiss of white wine reducing—set a tempo I knew by heart. We were packed to the walls, and that was exactly how I’d designed it.

My sister Claire had picked the location. She’d texted me that morning with her usual, unpunctuated confidence: It’s the best seafood in the city. Perfect for a family dinner. You’ll love it. She had no idea.

I wrote back a single word: Confirmed.

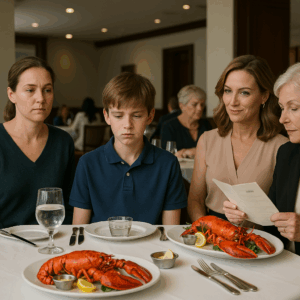

Tyler sat beside me in the leather booth, elbows tucked, the way fourteen-year-olds sit when they’ve been told not to crowd other people’s space. He’d grown three inches in four months and was charging through shirts and sneakers like a kid determined to outrun his own bones. Across from us sat my mother, Patricia, composed behind a pair of reading glasses she wore like a crown, and Claire’s twins, Sophia and Emma—sixteen, identical, and working the menus with the unhurried certainty of people who had learned that dining rooms existed for them.

“The Maine lobster is supposed to be incredible,” Claire announced, eyes still scanning the descriptions. “Fresh, flown in daily. Girls, you should try the lobster platter. It comes with drawn butter and everything.”

“Can I get that too?” Tyler asked, hopeful, cheeks flushed high as he traced the words with a finger.

“It sounds really good,” Claire said. She glanced at him, then at me, then back to the page as if the prices might rearrange themselves into something more palatable. “That’s a bit expensive for—well, you know.”

“For what?” I asked, even-voiced.

“For everyone,” she said finally. “We’re celebrating Sophia and Emma getting into their top college choices. This dinner is for them. Everyone else should probably order more modestly.”

Tyler’s eyebrows knit. “But you just told them to get the lobster.”

“They’re the guests of honor, sweetie,” Claire said brightly. “Different situation.”

The server arrived then: Ashley, hair neatly pulled back, posture as precise as a ballet line. Her name tag flashed at her left collarbone. I recognized it because I had approved her hiring three months earlier. She didn’t acknowledge me beyond a professional smile. Good. We trained for that.

“Good evening, everyone,” she said. “Can I start you with drinks?”

Claire ordered a bottle of chardonnay for the table, one I knew was priced to signal celebration without scaring away the timid. My mother ordered a martini, extra cold. The twins asked for sparkling water with lemon—synchronous, like choreography they’d rehearsed. Ashley turned to Tyler.

“And for you, young man?”

“Just tap water for him,” Claire cut in. “Regular glass. Nothing fancy.”

Tyler’s face fell almost imperceptibly, a shutter dropping. He didn’t argue. He’d learned how noise worked in our family: who got to make it and who was expected to absorb it.

Ashley wrote without looking up, then left in a quiet slip of motion. I breathed through the sting that rose anyway.

“Claire, that was rude,” I said, low enough not to travel.

“What?” She blinked, innocent. “I’m trying to keep costs reasonable. You know how expensive these places are.” She lifted the wine list with two fingers, as if it weighed more than it did. “We don’t need to go overboard for everyone.”

“You just ordered a seventy-five-dollar bottle of wine,” I reminded her. “For the celebration.”

“Exactly. Not everyone needs the full treatment,” she said. “Some people are here to celebrate, and some people are just extras.”

I let the word hang. “Extras,” I repeated.

“You know what I mean,” Claire said, already sliding her eyes back to the menu. “Like in a movie. Some people are the main characters, some are supporting cast, and some are just background. Extras. They’re there, but they’re not really part of the story.”

My mother set down her menu and folded her hands like a judge coming to the bench. “Claire’s right,” she said. “Tyler should understand his place at this dinner. It’s about the girls and their achievement. Not everyone gets to be the center of attention.”

Ashley returned with the drinks. She placed the chardonnay glasses with measured care, poured for my mother and for Claire, then set down sparkling waters at the twins’ elbows. She reached into her tray and pulled out a simple water glass—the kind we used for tap water—and slid it across the table to Tyler. She didn’t place it. She slid it, a frictioned push, the way you’d move a bowl toward a dog that wasn’t your responsibility. It wasn’t a cruel gesture; it was a gesture that said she took her cues from the people who looked like decision-makers.

Tyler picked up the glass without looking at anyone. I felt a heat in my chest that had nothing to do with the dining room.

“Are we ready to order?” Ashley asked.

“Yes,” Claire said briskly. “The girls will both have the Maine lobster platters with drawn butter and garlic roasted potatoes. I’ll have the sea bass. Mom?”

“The scallops,” my mother said, settling back as if she’d earned them.

Ashley wrote it all down, then looked at me. “And for you?”

“The lobster platter as well,” I said.

“Excellent choice.” She tipped her pen toward Tyler. “And for the young man—”

“He’s fine with the water,” Claire said before Tyler’s mouth could open. “We’re not ordering for him.”

Ashley’s pen paused. “I’m sorry—nothing at all?”

“We don’t feed extras,” Claire said, casual as weather. “He can eat at home later.”

Ashley’s gaze flicked to me. I saw the moment of recognition: not just my face but my place. She knew this was wrong. She also knew her job. She waited for my direction.

I smiled at Claire. “Noted.”

“What does that mean?” Claire asked.

“It means I heard you,” I said. “Please continue.”

Ashley lifted the menus from our hands and left as if nothing had happened. Tyler sat very still, eyes on the condensation sliding down his water glass like rain on a window he wasn’t allowed to open. Across from us, Sophia and Emma shifted, discomfort trying to find a polite chair at the table. Neither of them spoke. Neither of them had to.

Appetizers arrived: oysters on crushed ice, lemon wedges like small suns, a mignonette glinting violet in the low light. Claire had ordered them “for the table,” a phrase that usually means generosity but sometimes just means control. Tyler watched everyone else eat. I didn’t touch mine.

“Amanda, you’re not eating,” my mother observed.

“I’m not hungry,” I said.

“Suit yourself,” she said, and reached for another oyster. “More for the rest of us.”

Conversation flowed around Tyler like he wasn’t there. Claire narrated the twins’ college acceptances with the theatrical pacing of a gala host: the campuses, the welcome packets, the choice between dorms with their ancient bricks and dorms with their gleaming gyms. My mother praised their achievements on a loop, as if repetition could lacquer pride into permanence. The twins basked under the light like well-placed centerpieces. Tyler drank water and made himself small.

When the entrées came, Ashley placed the lobster platters in front of Sophia and Emma with a quiet, practiced cadence, tracing each component with a gracious finger: the tail and claws, the drawn butter, the potatoes. She set the sea bass before Claire, the scallops for my mother, and finally, my lobster platter, which I had no intention of touching. There was nothing for Tyler. He watched his cousins crack through shell, pull the sweet white meat free and anoint it in gold. Their appreciative sounds were tiny fireworks designed to be overheard.

“Oh my God, this is amazing,” Sophia said, offering her mother a taste.

“Worth every penny,” Claire replied after savoring the bite.

Tyler took another sip of water and swallowed hard. The room pitched slightly, as if a ship had crossed a line of current.

That was when Chef Michael stepped out of the kitchen. He always did a walk-through in prime hours—eyes traveling over tables, scanning for anything off tempo. He was heading our way. I stood up as he approached.

“Chef,” I said, loud enough for nearby tables. “Could you join us for a moment?”

Michael stopped, surprised. “Of course. Is everything satisfactory?”

“The food is excellent as always,” I said. “But I wanted to introduce you to my family. My sister, Claire. My mother, Patricia. My nieces, Sophia and Emma. And this is my son, Tyler.”

Michael greeted each of them with his kitchen-honed politeness, then looked at me with questions I could answer without words.

“Michael has been the head chef here at Meridian for almost two years,” I said to the table. “He’s extremely talented. We’re lucky to have him.”

“Thank you,” Michael said carefully. “The restaurant has been very successful.”

“It should be,” I said, meeting Claire’s eyes. “I invested quite a lot to make sure it would be.”

Claire’s fork stalled midair. “You invested?”

“Actually,” I said. “I should clarify. I don’t just invest in Meridian. I own it.” I let the sentence land. “Purchased it outright eighteen months ago. Michael reports to me, as does everyone working tonight.”

The table fell quiet enough to hear the chill cracking on my mother’s martini.

“What?” Claire said. “You… own this?”

“I own this restaurant, the building, the business, the entire operation,” I said. “When you made this reservation, you made it at my establishment.”

My mother set down her wine glass, voice changing registers. “Amanda, is this true?”

“Completely true,” I said. “I own Meridian. I also own two other restaurants in the city—The Harbor View and Lucius. This is my business.”

Ashley had paused at a station within earshot. I gestured for her to come over.

“Ashley,” I said in the same even tone I used in pre-shift meetings. “Would you please tell my family who I am?”

Ashley looked nervous but composed. “This is Amanda Foster,” she said. “She’s the owner of Meridian Restaurant Group. She owns this restaurant and two others. She’s my boss.”

“Thank you,” I said, then returned to Claire. “So when you said, ‘We don’t feed extras,’ and slid a water glass to my son—your nephew—at this dinner you arranged, at my restaurant, you were telling my employee not to feed my child in my own establishment.”

Color moved through Claire’s face in a violent gradient. “I… I didn’t know.”

“You didn’t know because you never asked,” I said. “You assumed I was still struggling, still living paycheck to paycheck. You assumed you could bring your family to an expensive restaurant, order sixty-dollar lobster platters for your daughters, a seventy-five-dollar bottle of wine, appetizers for the table, and classify my fourteen-year-old son as an extra who doesn’t deserve food.”

“Amanda, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean—”

“You told him to know his place,” I said. “That some people are main characters and some are extras. You had a water glass slid to him like he was a stray dog.”

My mother found her voice. “Amanda, there’s no need to make a scene.”

“Actually,” I said, the word sharper than a knife tip. “There is. Because you backed her up. You told your grandson he should know his place at a dinner celebrating his cousins. You agreed he was background—that he wasn’t worthy of a meal.” I turned to Michael. “Chef, my son would like to order now. Tyler, what would you like?”

Tyler looked up at me, eyes glass-bright. “The lobster platter.”

“The lobster platter for my son, please,” I said. “And bring out the special reserve sides—the truffle mac and cheese, the grilled asparagus—and the chocolate lava cake for dessert. Also, I’d like you to prepare one of your off-menu specials for him. Your choice. Whatever you think a fourteen-year-old who just got called an extra would enjoy.”

Michael’s mouth lifted at one corner. “I have just the thing,” he said. “I’ll take care of it personally.”

After he left, I sat down. The nearby tables had gone quiet in those quick, guilty silences of strangers who can’t help but witness each other’s lives. Claire stared at her napkin as if it could translate what had just happened into a language she preferred.

“Amanda, please,” she said, voice pitched for privacy that the room wouldn’t grant. “This is humiliating.

“It’s interesting that you feel humiliated,” I said. “How do you think Tyler felt watching your daughters eat lobster while he drank tap water? Being told he’s just an extra?”

“I apologized,” she said.

“You apologized after learning I own the restaurant,” I said. “Would you have apologized if I still matched the story you were telling yourself about me?”

She opened her mouth, then closed it.

My mother cleared her throat. “We should discuss this privately,” she said, the way people do when privacy means preservation of hierarchy.

“No,” I said. “We’re discussing it now. Because you both need to understand something. I’ve spent the last six years building a restaurant business. I started with a food truck. I worked ninety-hour weeks. I learned every aspect of this industry. I bought my first restaurant three years ago. I’ve been successful—very successful. You never asked.”

Claire spread her hands, helpless. “You should have told us.”

“I didn’t because you never asked,” I said. “You were busy assuming I was failing. Busy teaching your daughters that some people matter more than others. Busy making sure Tyler knew he was background.”

Tyler’s meal began to arrive in a parade that re-ordered gravity: the lobster platter scaled to his appetite, the truffle mac and cheese with its confident perfume, the asparagus charred to sweetness. Michael himself set down a small Wagyu slider on a warm plate, an off-menu kindness that felt like the opposite of a slid glass.

“This looks amazing,” Tyler said, almost whispering to the food as if it might startle.

“Enjoy,” I told him. “All of it.” Then I looked at Claire. “The bill for tonight will be interesting. Your table has run up about four hundred dollars so far. That bottle of wine alone was seventy-five. The lobster platters are sixty each. Would you like me to comp the meal—or would you prefer to pay for it yourself?”

Claire’s panic was immediate and naked. “I… I assumed you’d—”

“You assumed I’d pay because I own the restaurant,” I said. “The same restaurant where you said we don’t feed extras. Where you had water slid to my son like he was beneath you.”

“Amanda, please.”

I stood. “Tyler, grab your food. We’re moving to a different table.” I looked to Ashley. “Would you prepare a private table for two in the back room and bring the check for this table?”

“Of course,” Ashley said, professional composure barely disguising the flint in her eyes.

“Wait,” Claire said, rising halfway. “You can’t just leave us with a four-hundred-dollar bill.”

“Watch me,” I said. “You brought your family to celebrate your daughters. You made it clear who matters and who doesn’t. You’ve eaten your celebration meal. Now you can pay for it.”

“I don’t have that kind of money right now,” Claire said.

“Then perhaps you should have been more thoughtful about ordering sixty-dollar lobster and seventy-five-dollar wine when you planned to classify a child as not worthy of eating,” I said. “Ashley, the check.”

Ashley nodded and disappeared in a clean line of motion. Tyler lifted his plate, the way kids lift things that feel too good to be theirs. We walked to the private dining room—a space I’d designed for client dinners, with glass that muted the main room into a moving painting. The door closed behind us with a soft seal.

“Mom,” Tyler said once we were seated again, “why did Aunt Claire call me an extra?”

“Because some people measure worth by money and status,” I said. “They think some people are important and some are just there. She was wrong.”

“But you own this place,” he said. “You’re… important.”

“I own this place because I worked hard,” I said. “But that’s not what makes someone important. You’re important because you’re you. Because you’re kind and smart and decent, not because of where you sit at a restaurant table.”

He took a bite of lobster and closed his eyes the way people do when something reminds them that joy is a skill. “This is really good.”

“Good,” I said. “Eat as much as you want. It’s your restaurant, too.”

Through the glass partition, I saw Claire and my mother in a heated geometry: hands, lean-ins, the frantic search for a solution that didn’t require the only solution available. The twins looked like girls whose mirrors had grown eyes. Ashley approached their table; there was the quick exchange of cards and signatures. A few minutes later, she came to us.

“They asked me to tell you they’ve left,” she said softly. “The bill has been paid. They wanted me to say they’re sorry.”

“Did they say it to you,” I asked, “or am I supposed to pass it along?”

“They said it to me, ma’am,” Ashley said. “Asked me to convey it.”

“Thank you,” I said. “And I’m sorry you had to witness that.”

“If I’m honest,” she said, professional even in honesty, “it was… satisfying to watch you handle it. What they said about your son was awful.”

After she left, Tyler was quiet for a long time, working through a plate and a feeling. “Are they going to hate you now?” he asked.

“Maybe for a while,” I said. “But listen to me, Tyler. You are never an extra. Not in your own life. Not in anyone’s story. You’re the main character in your own story. And anyone who treats you as less than that doesn’t deserve to be in it.”

“Even family?”

“Especially family,” I said. “Because family should know better.”

We finished dinner: all three courses, plus dessert—a lava cake that broke like gratitude. When we finally walked out of Meridian, it was close to ten. Outside, the night had that late-city shine, streetlights making promises to asphalt. In the car, Tyler watched the restaurant through the passenger window as if it were a theater premiere he’d managed to enter without a ticket. He didn’t speak until we’d turned onto our street.

“Mom,” he said, “can I ask you something?”

“Anything.”

“Did you really buy three restaurants?”

“I did.”

“That’s pretty cool.”

“Thanks, buddy.”

“And you named one of them Lucius after your grandmother—your mom’s mother—the one who always said I was special?”

“That’s the one,” I said. “She would have loved watching you eat that lobster tonight.”

He smiled, small and true. “I think she would have liked watching you tell Aunt Claire off even more.”

He was probably right. Some people learn to know their place, and some people learn to own the place. My son learned the difference at a table that belonged to him as much as it belonged to me.

If the evening ended there—on the asphalt, the neon, the words exchanged in the car—it would have been enough. But stories don’t end in the heat. They end in the cool. They end in kitchens.

At home, the house exhaled as we walked in. I set my keys in the bowl and felt the exact shape of the day’s weight in my shoulders. Tyler carried the leftover box—because he had leftovers and because that mattered—to the refrigerator and slid it onto a shelf with ceremony.

“Do you want tea?” I asked.

He shrugged the universal teenage shrug of open-ended yes. I set water on the stove and leaned on the counter, watching his reflection move in the dark window like a companion. He looked taller at night.

“Mom?” he said after a minute.

“Yeah?”

“Did they ever… treat you like that? Grandma and Aunt Claire?”

I thought about it, about how truths sound at fourteen versus how they sound at forty. “In different ways,” I said. “Sometimes it was loud. Sometimes it was quiet. It’s not new.”

He nodded like he knew, because children collect evidence long before anyone admits there’s a case.

“What did you mean when you told Aunt Claire they never asked?” he said.

“I mean they didn’t ask about my life,” I said. “They didn’t ask how the food truck was going when I was sleeping four hours a night and splitting shifts between the grill and the books. They didn’t ask how I bought Meridian—what it took to sit across from a banker who called me ‘sweetheart’ while deciding whether to believe my numbers. They didn’t ask how many times I drove home at two in the morning and parked and just sat in silence so the house wouldn’t feel like failure. They didn’t ask. They assumed.”

“And you didn’t tell them,” he said.

“I told people who could hear me,” I said. “Sometimes you have to stop throwing your voice into rooms that dim the lights when you arrive.”

The kettle clicked. I poured water over tea bags and watched the steam lift like something you’d set free. I handed him a mug. He cupped it in both hands the way he had cupped the water glass earlier, except this time, he did it without making himself small.

“You handled it,” he said.

“I did what needed doing,” I said.

He sipped, then grinned. “You were kind of a boss.”

“I am a boss,” I said, and he laughed, and the sound filled the kitchen with something Meridian couldn’t contain.

I slept like people do after a verdict: not early, not easily, but completely once it arrived. Morning came with its usual clarity. The city was a different machine in daylight—same gears, less theater. I answered a few emails before my first meeting, signed off on a produce order, and approved a maintenance request that had needed a manager’s yes but not my time. The night before pulled at the edges of my focus, not to distract but to clarify. Lines had been drawn. Some lines you draw for yourself so that other people’s chalk can’t scuff the places you live.

My phone buzzed with a text from Claire at 9:17 a.m. It began with my name—always a tell that someone is calibrating themselves into reason. I stared at it until the screen dimmed, then slipped the phone into my bag. There’s an art to not answering right away. It’s not punishment. It’s hygiene.

At Meridian, the morning crew moved in their easy rehearsal: servers rolling polished flatware into napkins, the barback stocking limes, Michael already in whites, reading a delivery invoice as if the paper could lie. He looked up when I stepped into the kitchen.

“Owner,” he said with a small bow he reserved for jokes and days he felt protective.

“Chef,” I said. “Last night—thank you.”

He shrugged in a way that meant the opposite. “The slider was a good call,” he said. “Kid needed joy without permission.”

“He did,” I said.

Ashley caught my elbow in the corridor between the line and the service station, that narrow channel where gravity changes and little things can become big ones. “Mrs. Foster,” she said. “I just wanted to say—if it matters—I thought you were… the word is not heroic, because that cheapens things. You were exact.”

“Thank you,” I said. “Exact is what I was aiming for.”

She nodded once. “Your son is a good kid.”

“He is,” I said.

That night I cooked at home. It wasn’t fancy—grilled chicken, green beans, a pile of mashed potatoes that needed more salt than I remembered to add on the first pass. Tyler set the table without being asked, which is one of those things you think you’ll have to remind boys to do and then one day realize you don’t. We ate and talked about school, about nothing, about everything. When dishes were done, we sat on the couch, his long legs claiming a geography they hadn’t owned last year.

“Mom,” he said. “If Aunt Claire invites us to dinner again—”

“We’ll decide then,” I said. “Boundaries aren’t walls. They’re doors that lock if people ignore the bell.”

He nodded. “Okay.” Then he settled deeper into the couch and, after a while, fell asleep with his head on my shoulder like he had when he was five, when everything about the world could be fixed by getting horizontal and knowing you were not alone.

People think the hardest part of owning restaurants is the hours. Or the margins. Or the personalities that come bundled with talent like fireworks that won’t be told when to explode. Those are hard, sure. But the hardest part is the quiet accounting you do when no one is watching: who you are when you have keys; who you become when people finally treat you the way you learned to treat yourself. Last night had been an audit. We passed.

Two days later, a card arrived in the mail with a handwriting I knew from school permission slips and notes excusing me from P.E. “We are very proud of the girls,” my mother had written. “We hope to celebrate you soon.” There was no mention of Meridian, or Tyler, or the words she had said at the table. I set the card on the counter like a museum piece from an era we were no longer funding.

Tyler looked at it when he got home from school. “Are we going to the celebration?” he asked.

“We’ll see,” I said. “I’m proud of your cousins. And I’m proud of you.”

He smiled sideways. “For eating lobster?”

“For existing like you,” I said. “The rest is garnish.”

He opened the refrigerator and pulled out the leftover box, which had somehow become a symbol. He ate standing at the counter, a fork in one hand, doing that bounce he did when food caught him by surprise. “Still good,” he said through a mouthful.

“Some things stay good,” I said. “Even after the heat.”

A week passed. Life does that thing where it returns to its level. Meridian pulsed; Harbor View glowed; Lucius kept its quiet promises. I rotated between them like a parent trying not to play favorites while knowing, privately, which child could actually do their own laundry. Ashley was promoted to shift lead. Michael floated a new seasonal dish across the pass and grinned when I said yes without asking the food cost. Tyler’s math teacher emailed to say he’d helped another student after class without being asked. I forwarded the email to myself, then again, then printed it and put it in a drawer I was saving for proof.

And on a Thursday evening when the city’s light tilted late and forgiving, Tyler and I walked past Meridian on our way to a movie we weren’t sure we’d stay awake for. He slowed, peering in through the front window like he was checking on a sleeping animal he both trusted and didn’t, yet.

“Want to say hi to Ashley?” I asked.

He shook his head, then nodded, then laughed at himself. We stepped inside. The host greeted us with the settled kindness of someone who understood without being briefed. Ashley spotted us and waved. Michael lifted a hand from the pass, then returned to a pan that had opinions. For a second, the room paused and tilted toward us, not as a spotlight but as a welcome. Tyler’s shoulders softened in a way that told me the room now knew his name, not as a word to call a busboy with, but as a person to serve without the lesson attached.

We left after a minute, because we had a movie to see and a night to keep. On the sidewalk, Tyler said, “It feels different in there.”

“It is different,” I said. “Because you are.”

He took my hand the way fourteen-year-olds don’t, usually. We walked. The city gave us exactly what we needed: a humid breeze that pretended to be a wind, a traffic light that stayed green longer than it had to, a stranger who smiled at us as if she’d overheard a good story and was glad for its ending.

People ask me—sometimes—what I’d say to Claire now if the table appeared again, if the wine was poured, if the menus opened, if the word extras tried to fit its mouth around my son’s name a second time. I wouldn’t say anything. I’d do what I did. Words are for the people who listen. Power is for the moments when listening has failed.

I’ve thought about that water glass a lot. About the skid of it. About how something can be a small movement and a declaration at the same time. We don’t feed extras, she said, and the glass moved like a verdict with fingerprints. I won’t forget it. I won’t need to. Memory has a way of turning sharp things into keys.

Here’s what I do know, for certain and for always: Tyler will never sit at a table where his worth is measured by what someone else ordered. He will never drink from a glass that arrives as an afterthought. If that means fewer tables, so be it. The ones that remain will be ours.

On a Sunday afternoon not long after, we sat together on the floor of the living room, a mess of takeout containers between us because even people who own restaurants sometimes need to let other people do the cooking. Tyler picked up a dumpling with chopsticks he was still learning to trust and said, “Mom, am I still the main character when I mess up?”

“Especially then,” I said.

He smiled the grin that belonged to a five-year-old and a fourteen-year-old at once. “Okay.” He chewed, then said, “Can we get lobster again sometime?”

“We can get whatever you want,” I said. “We own the place.”

He laughed, towheaded and tall and entirely himself. The sun moved along the wall like a curtain shift before the next act. Outside, the world kept dining and deciding and teaching itself lessons it would claim later it already knew. Inside, my son and I ate and talked and existed in a story where no one had to be asked to be fed.

And if Meridian was busier than usual that night—if the tables filled, if the drinks were poured, if the kitchen sang at full capacity—it wasn’t because people had heard a story. It was because places are shaped by what they hold. We held the line. We kept the table. We taught the room our names.

That is all a restaurant ever is. That is all a family should be.

News

After twelve years of financial support, my parents texted: “You’re not welcome for Christmas. Your sister’s husband needs family space.” I didn’t argue. I simply replied, “Okay.” Then I called my lawyer, opened a spreadsheet, and quietly calculated the total amount I had given them over the years — $520,142.68.

I. The Message After twelve years of financial support, my parents texted: “You’re not welcome for Christmas. Your sister’s husband…

My Parents Left Me At A Train Station As A joke! «Let’s See How She Finds Her Way Home» – I Never Went Back…

I am Megan Miller, 32, a graphic designer in Chicago. This morning, my phone lit up. 29 missed calls from…

My Pilot Sister Saw My Husband on a Business-Class Luxury Flight to Paris with Another Woman

My sister, an airline pilot, called me. “I need to ask you something strange. Your husband—is he home right now?”…

A Mother Worked Collecting Trash, Her Daughter Was Mocked for 12 Years — Then at Graduation, One Sentence Made the Entire Hall Rise in Tears

Part One: The Weight of Whispers Emma Walker learned early that cruelty doesn’t always announce itself with fists or screams….

The Day Before My Wedding, I Visited My Late Wife’s Grave — I Never Expected to Meet Her

Tomorrow, I’m marrying Emily—the woman who waited for me patiently for three long years. Everything’s ready. Both families have poured…

HE’S BACK… FOR NOW. JON STEWART JUST EXTENDED HIS DAILY SHOW DEAL — BUT THIS RENEWAL RAISES NEW QUESTIONS 🔍📺 Jon Stewart isn’t leaving The Daily Show yet — but the way this deal came together has fans asking more than a few questions. Why did it take this long? Why renew now, right after Colbert was dropped without warning? And what’s Paramount’s long game with politically outspoken hosts heading into another election year? Stewart will keep hosting Monday nights through 2026, but with everything shifting in late-night — from canceled contracts to behind-the-scenes politics — is this a vote of confidence… or just a delay in the inevitable?👇

As late-night continues to evolve and contracts expire, Stewart’s return offers some welcome stability — and plenty more Monday night…

End of content

No more pages to load