The closest star to us is, of course, the Sun. It’s not going to explode, but if it had about eight times its current mass, it would end its life in a supernova. So what would that look like?

As the comic xkcd has pointed out, if you held a hydrogen bomb right up to your eye and detonated it, that explosion would still be about a billion times less bright than watching the Sun go supernova from Earth. That’s how unbelievably powerful supernova explosions are. They are among the largest explosions in the universe.

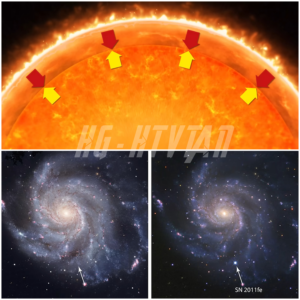

When we see supernovae in other galaxies, they can outshine the combined light of hundreds of billions of stars. They get so bright that they appear to come out of nowhere.

On October 8, 1604, the astronomer Johannes Kepler looked up at the night sky and noticed a bright star he had never seen before. It outshone all the other stars and was about as bright as the planet Jupiter. On moonless nights, it was so bright that it could cast a shadow. Kepler published his observations in a book called De Stella Nova—Latin for “About a New Star.” He thought he was witnessing the birth of a new star, but in reality, he was seeing a star’s violent death.

Over the next year and a half, the light faded until the star was no longer visible. The term “nova” stuck, and even after we learned in the 1930s what was really going on, the violent final explosions of stars with masses between about 8 and 30 times that of the Sun have been called supernovae.

However, how a star actually explodes is not what most people imagine.

How Stars Live and Die

For most of a star’s life, it exists in a stable balance. In its core, it fuses lighter elements into heavier ones, and in the process converts a small amount of matter into energy. That energy is what prevents the star from collapsing under its own gravity.

Gravity is always trying to compress the star inward, but this inward pull is balanced by the outward pressure generated by the motion of particles inside the star and by the radiation (photons) produced by fusion. In a sense, stars are literally held up by their own light.

If the fusion rate in the core drops, the temperature and pressure decrease. Gravity starts to win and compresses the star, which heats the core back up and increases the fusion rate again. This feedback makes the star a stable, self-regulating system.

But there’s a problem: stars have a finite supply of fuel, and over time, they use it up.

Our Sun is about 5 billion years into its roughly 10-billion-year lifespan. You might expect more massive stars to live longer because they contain more fuel, but they actually burn through it much faster. A star with 20 times the mass of the Sun has a lifespan of only about 10 million years. More massive stars burn hotter and shine brighter, but they live much shorter lives.

For about 90% of a star’s life, its core is hot enough only to fuse hydrogen into helium. When the hydrogen in the core runs out, fusion slows down, gravity compresses the core, and the temperature rises to around 200 million degrees. At that point, helium can start fusing into carbon.

There is enough helium to power the star for around a million years. But eventually that helium gets used up too, and once again the core contracts and heats up. The star then begins a series of successively shorter-burning fusion stages:

Carbon fuses into neon for about 1,000 years

Neon fuses into oxygen for a few more years

Oxygen fuses into silicon for a few months

At about 2.5 billion degrees, silicon fuses into nickel, which decays into iron

At this stage, a dense iron core forms at the center of the star. It’s only a few thousand kilometers across, but it sits at the heart of a giant star.

Why Iron Is the End of the Line

Iron is where the pattern of energy-producing fusion stops. Fusing lighter elements into heavier ones up to iron releases energy. But iron is the most stable element in terms of nuclear binding energy, so fusing iron into heavier elements, or breaking it apart into lighter elements, actually consumes energy rather than releasing it.

In other words, both fusion and fission tend to “end” at iron. Once a star’s core is mostly iron, fusion can no longer provide the outward pressure needed to counteract gravity.

The iron core continues to grow, but as the rate of fusion in the surrounding layers drops, gravity’s inward pull becomes more and more dominant. When the iron core reaches about 1.4 times the mass of the Sun—a value known as the Chandrasekhar limit—gravity becomes so strong that something dramatic happens: quantum mechanics takes over.

Electrons in the core run out of available space and are forced into their lowest energy states. Many of them get captured by protons in atomic nuclei. In this process, protons are converted into neutrons and neutrinos are emitted.

With the electrons gone, a key source of pressure disappears, and the core collapses extremely quickly—at about 25% of the speed of light. A ball of iron roughly 3,000 kilometers across shrinks down to a sphere of neutrons only about 30 kilometers across. This ultra-dense object is a neutron star.

With no longer any outward pressure to support it, the rest of the star’s material comes crashing inward. Falling at around a quarter of the speed of light, it slams into the newly formed neutron star and bounces off, creating a huge pressure wave. But even that kinetic energy is still not enough on its own to power a full-blown supernova explosion.

The Surprising Role of Neutrinos

The real trigger for the explosion comes from the seemingly insignificant neutrino.

We usually think of neutrinos as particles that almost never interact with anything. Right now, roughly 100 trillion neutrinos are passing through your body every second. They interact so weakly with matter that you would need about a light-year of solid lead just to have a 50–50 chance of stopping a single neutrino. They only interact via gravity and the weak nuclear force.

But in a collapsing stellar core, when huge numbers of electrons are captured by protons, an incredible number of neutrinos are produced—on the order of 10^58 of them. You might expect them to just fly out at nearly the speed of light, but the core of a supernova is staggeringly dense—about 10 trillion times denser than lead. Because of this density, some of those neutrinos get trapped long enough to transfer part of their energy to the surrounding matter.

That captured neutrino energy is what finally drives the star to blow itself apart as a supernova. A particle that is millions of times less massive than an electron and that almost never interacts with anything turns out to be responsible for some of the largest explosions in the universe.

In a typical core-collapse supernova:

Only about 0.01% (one hundredth of one percent) of the total energy is emitted as electromagnetic radiation—the light we see.

Around 1% of the energy goes into the kinetic energy of the exploding material.

The vast majority of the energy is carried away by neutrinos.

Neutrinos are actually the first signal we detect from a supernova, because they can escape from the core before the shockwave reaches the surface of the star and produces visible light. Neutrinos can reach Earth hours before the first photons, giving astronomers an early warning and time to point their telescopes in the right direction.

I actually worked at a neutrino observatory back in college, on the graveyard shift from midnight to 8:00 a.m. If we’d seen a sudden, large spike in the neutrino flux during my shift, it would have been my job to call and wake up the scientists so they could look for a supernova. That never actually happened, but we did have some close calls.

Not All Massive Stars Go Supernova

There are a couple of important clarifications:

Not all very massive stars explode.

Some stars collapse directly into black holes without producing a visible supernova.

There is another way to make a supernova.

A white dwarf—an already extremely dense stellar remnant—can pull matter from a companion star. When the white dwarf’s mass approaches the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 solar masses, it can no longer support itself and collapses, triggering a thermonuclear supernova.

This type of event is known as a Type Ia supernova, and it’s actually the kind of supernova Kepler observed in 1604, about 20,000 light-years from Earth.

Because the explosion can be asymmetric, the resulting neutron star can be kicked to very high speeds. We’ve observed neutron stars moving at 1,600 kilometers per second, likely launched by such uneven supernova explosions.

Supernovae Through History

Even though we’ve only recently started to understand the physics of supernovae, humans have been observing them for thousands of years. Ancient Indian, Chinese, Arabic, and European astronomers all recorded supernovae. However, they are rare. In a galaxy like the Milky Way, with roughly 100 billion stars, there are only about one or two supernovae per century.

A famous historical example is the supernova of 1054, whose light reached Earth from a star about 6,500 light-years away and was recorded by Chinese astronomers. When we look today at the location of that event, we see the Crab Nebula—a giant, expanding cloud of radioactive debris left over from the explosion. In the ~1,000 years since the supernova, the nebula has grown to about 11 light-years in diameter.

Supernovae also produce a large number of cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are not rays in the usual sense, but high-energy particles—mainly protons and helium nuclei—traveling at very nearly the speed of light. They carry enormous amounts of energy.

How Close Is Too Close?

So at what distance could a supernova seriously affect life on Earth?

The nearest stars to us, aside from the Sun, are the three stars in the Alpha Centauri system, about 4.4 light-years away. Stars move around the galaxy, and on average, another star passes within about one light-year of Earth every 500,000 years.

If a star went supernova within about a light-year, we’d be easily within the danger zone just from the kinetic energy and intense radiation. At that distance, it’s possible we could even lose a large portion of the atmosphere.

But there are other problems too. Supernovae create environments hot enough to generate elements heavier than iron. In the months after the explosion, these elements undergo radioactive decay, emitting gamma rays and cosmic rays.

Even though less than 0.1% of a supernova’s energy is emitted as gamma rays from these decays, that small fraction can still be dangerous. At a distance of a few light-years, the radiation could be deadly, though our atmosphere would block a lot of it.

Earth is protected from solar and cosmic radiation primarily by its atmosphere, and especially by ozone molecules—O₃, molecules of three oxygen atoms. High-energy cosmic rays from a nearby supernova can collide with nitrogen molecules in the atmosphere, breaking them apart. The resulting nitrogen atoms can combine with oxygen to form nitrogen oxides, which in turn can destroy ozone.

If too many cosmic rays bombard the atmosphere, we can lose a significant fraction of our ozone layer, exposing the surface to much more harmful ultraviolet and other radiation from space.

We actually see increases in atmospheric nitrate (NO₃) concentrations that coincide with supernova events, which supports this picture.

A supernova within about 30 light-years is thought to be quite rare—maybe occurring once every 1.5 billion years or so. However, recent research suggests that supernovae could be lethal out to distances of 150 light-years, which would make dangerous events much more common.

Evidence of a Nearby Supernova

We have evidence that a supernova did go off about 150 light-years from Earth approximately 2.6 million years ago. Our early human ancestors, such as Australopithecus, would have seen it in the sky.

We know this because scientists have found elements on Earth that could only have been deposited by a recent supernova. In sedimentary rocks on the Pacific Ocean floor, they’ve detected traces of iron-60 in layers dated to about 2.6 million years ago.

Iron-60 is an isotope of iron with four more neutrons than the most common form. It’s very hard to produce: our Sun doesn’t make it, and it’s not created in significant amounts elsewhere in the solar system. Iron-60 is produced almost exclusively in supernova explosions.

Iron-60 is also radioactive, with a half-life of about 2.6 million years. That means every 2.6 million years, half of any given sample decays into cobalt-60. Since Earth formed 4.5 billion years ago, any iron-60 originally present has long since decayed away. So the iron-60 we measure today must have arrived recently, on geological timescales, likely from a nearby supernova.

Scientists have also found trace amounts of manganese-53 in the same sediments, providing further support for the idea of a recent nearby supernova.

The supernova 2.6 million years ago wasn’t catastrophic for our ancestors, but some researchers hypothesize that it may be linked to a mass extinction seen at the Pliocene–Pleistocene boundary, around the same time. This event wiped out about one-third of marine megafauna.

The idea is that cosmic rays from the supernova hit particles in Earth’s atmosphere, producing muons—charged particles similar to electrons, but more than 200 times heavier. For years after the supernova, the muon flux at Earth’s surface would have been about 150 times higher than normal. The larger the animal, the larger the radiation dose it would receive from these muons, which could explain why large marine animals were disproportionately affected.

Moreover, animals living in shallow waters would have been more exposed than those in deeper regions, where water provides shielding from muons. This could explain patterns in which species went extinct and which survived.

The Local Bubble

Additional evidence for multiple nearby supernovae comes from our position in the galaxy. On average, the interstellar medium in the Milky Way contains around one million hydrogen atoms per cubic meter. That might sound like a lot, but it’s an extremely good vacuum by Earth standards.

However, for hundreds of light-years in all directions around our solar system, the density drops by a factor of about 1,000. It’s as if the gas has been blown out, leaving us inside a vast low-density region known as the Local Bubble.

This suggests that tens of supernovae may have exploded in our galactic neighborhood over the last few million to tens of millions of years, blasting the surrounding gas outward and creating the bubble we now inhabit.

Even More Dangerous: Gamma-Ray Bursts

There are cosmic explosions even more dangerous than ordinary supernovae: gamma-ray bursts (GRBs).

Gamma-ray bursts were first discovered by the Vela satellites, which were originally designed to monitor for nuclear tests by the Soviet Union. On July 2, 1967, the satellites detected a large burst of gamma rays—but the signal was coming from space, not Earth.

We now know that there are two main types of GRBs:

Mergers of neutron stars

Core collapses of very massive, rapidly spinning stars—hypernovae

Hypernovae occur in stars with at least about 30 solar masses that are rotating quickly. Their collapse leads to an explosion about 10 times more powerful than a regular supernova and leaves behind a black hole.

The gamma-ray bursts from hypernovae channel most of their energy into narrow beams only a few degrees across. If a GRB occurred within about 6,000 light-years and one of its beams happened to be pointed at Earth, it could deplete the ozone layer enough to be catastrophic for life.

To put that distance in perspective, a sphere with a radius of 6,000 light-years contains hundreds of millions of stars.

On October 9, 2022, astronomers observed one of the most powerful gamma-ray bursts ever recorded. It was strong enough to measurably affect how Earth’s ionosphere reflects radio waves. The impact on the ionosphere was similar to that of a solar flare—but this GRB took place in a galaxy about 2.5 billion light-years away.

Some scientists speculate that a gamma-ray burst might have caused the Late Ordovician mass extinction around 440 million years ago, which wiped out about 85% of marine species. There’s no direct evidence linking a specific GRB to that extinction, but GRBs are common enough that it’s estimated there’s about a 50% chance that an ozone-stripping, extinction-level GRB has occurred near Earth in the last 500 million years.

A Threat—and a Reason We Exist

If a supernova or gamma-ray burst were to occur near Earth today, it could be devastating. Yet, in a twist of irony, we likely owe our existence to such explosions.

About 4.6 billion years ago, a shockwave from a nearby supernova probably triggered the collapse of a cloud of gas and dust, which then coalesced to form our solar system. Without that explosion, the Sun, the Earth, and all of us might never have formed.

Figuring out how supernovae explode has been incredibly challenging. It required the combined efforts of astrophysics, particle physics, computer science, and mathematics. But through that work, we’ve come to understand not only how stars die, but also how those deaths help create the conditions for new stars, planets, and ultimately life itself.

News

Was General George S. Patton, America’s most famous WWII general, murdered in December 1945? And why?

It’s no exaggeration to say that George S. Patton was one of a handful of World War II generals whose…

General George. Patton was a dedicated and controversial soldier.

In December 1944, snow blanketed the battlefields of the Western Front. Exhausted Allied soldiers believed, and many generals quietly agreed,…

Japanese Pilots Laughed At America’s ‘Impossible’ Smart Shells, Until VT Fuses Shot Down 5 Out of 6

August 1943, somewhere in the Solomon Islands aboard the USS San Diego, Lieutenant Commander James Russell, chief gunnery officer, stood…

German Pilot Tested Captured American P-47 Thunderbolt – What He Discovered Changed Everything

November 10th, 1943. Afternoon, at Rechlin—Germany’s primary Luftwaffe aircraft testing facility. Hauptmann Hans-Werner Lerche, chief test pilot, walked across the…

WWI’s Deadliest Dogfighter: The Story of the Sopwith Camel | Aviation Documentary

By early 1917, the Royal Flying Corps was being torn apart over the Western Front. British pilots flew outdated aircraft…

The General Who Disobeyed Hitler to Save 20,000 Men from the Falaise Pocket

August 16th, 1944, 1600 hours. Generaloberst Paul Hausser stood in a farmhouse near Trun, France, studying a map that was…

End of content

No more pages to load