“You better start earning your keep.”

That was the first thing out of Gary’s mouth as he loomed over my hospital bed, blocking the little plastic American flag that was taped to the IV pole. I was three days out of emergency surgery, still in a stiff paper gown, hooked up to enough machines to light a Christmas tree. My abdomen felt like someone had driven a snowplow through it and tried to stitch the road back together in the dark.

“I can’t work yet,” I whispered. “The surgeon said at least two weeks.”

Gary’s jaw clenched. His bowling league championship ring flashed under the fluorescent lights as his hand came down.

The slap was so fast I didn’t even see it coming. One second I was propped up against cheap, flattened pillows; the next, the world snapped sideways. My head cracked against the bed rail, and my shoulder slid off the edge. I hit the floor hard enough to knock the breath out of me.

Cold hospital tiles pressed against my cheek. The antiseptic smell mixed with the metallic taste in my mouth until it felt like I was breathing in pennies and bleach. My hands trembled when I tried to push myself up.

“Stop pretending you’re weak,” Gary barked from above me. “I’m not paying for you to lie around and act helpless.”

His voice echoed down the hallway, past the nurses’ station where somebody’s Styrofoam cup of iced tea sat sweating under a little napkin. Machines behind me began beeping in protest. Somewhere, a woman gasped.

For a moment, all I could see was that ring—thick gold, 2019 CHAMPS etched into it, smeared now with a tiny spot of my blood.

I’m Rihanna Hester, I was twenty‑nine years old, and until that exact moment on the hospital floor, I thought I already knew what rock bottom felt like.

Turned out I’d just hit the trapdoor underneath it.

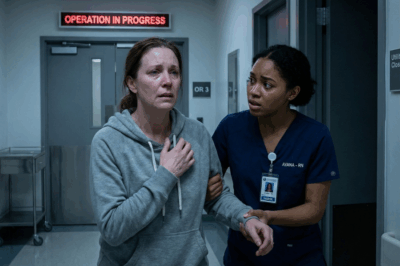

Nurses’ shoes squeaked as two of them rushed into the room.

“Ma’am, don’t move—Rihanna, can you hear me?” one of them said, dropping to her knees beside me.

“She fell,” Gary announced, hands in the air like he was narrating a magic trick gone wrong. “She’s being dramatic. She’s fine.”

“Sir, step back,” the other nurse snapped.

“I said I’m not paying for—”

The door banged open again. A security guard pushed in, already reaching for his radio.

“I need PD in room fourteen,” he said into the mic. “Possible assault.”

Gary’s face turned that familiar shade of purple I knew too well, like overcooked beets no one really wanted on their plate.

“You better watch what you’re implying,” he snarled. “This is family business.”

The guard planted himself between us. “And this is a hospital. You don’t put your hands on patients here.”

My surgical incisions screamed when I tried to roll onto my back. Every breath was a small explosion in my abdomen. The nurses were talking over me, checking my pupils, checking the monitors, checking the IV line that had yanked when I went down. One of them, the younger one with tired eyes and a cartoon bandage tattoo on her wrist, kept saying, “You’re okay. I’ve got you. You’re okay.”

Behind her, I saw my mother in the doorway.

She was pressed against the frame, hands at her mouth, eyes wide and glassy. She didn’t move. She didn’t run to me. She just… froze, like someone had hit pause on her entire body.

“Mom,” I croaked.

Her eyes flinched toward Gary instead.

“I told her,” he said to the room like we were all his audience. “She’s milking this. She’s been out of surgery, what, three days? I work hard for my money. I’m not supporting a freeloader.”

“Sir, you need to step outside,” the guard repeated.

Gary took a step toward me anyway. “Get up, Rihanna. You’re embarrassing yourself.”

By the time the police walked in, he was in full lecture mode.

“Kids these days have no idea what real work is,” he was saying. “You give them a free room, and suddenly they think they can just lie around all day. I’m trying to teach her some discipline. That’s all this is. Tough love.”

“Sir,” the taller officer said, “step back and keep your hands where I can see them.”

The other officer, a woman with her dark hair scraped into a bun so tight it probably had its own badge, looked down at me on the floor. Her gaze flicked from my split lip to the IV pole to the monitor now blinking red.

“What happened?” she asked quietly.

Before I could answer, Gary jumped in.

“She slipped. You know how these hospital floors are. I was just trying to help her back up and—”

“I watched you hit her,” my roommate’s voice cut across the room like a knife.

Mrs. Chen was eighty‑three, recovering from hip surgery, and done with everyone’s nonsense forever. She lay in the bed by the window, hand still hovering over her call button.

“I pressed this three times,” she said. “He slapped her so hard, the ring cut her mouth. Men who think their fists make them important are not welcome here.”

One of the nurses nodded. “I saw the strike. We’ll give statements.”

My mom finally stepped into the room.

“Gary’s just under a lot of stress,” she blurted. “The hospital bills, the time off work—he didn’t mean—”

The female officer’s jaw flexed. “Ma’am, we’re going to deal with that. Right now we need to make sure your daughter is safe.”

As they helped me back into bed, I caught a last glimpse of Gary over the officer’s shoulder. His hands were cuffed behind his back. His face had gone from beet‑purple to a strange, chalky white.

The ring still glinted on his finger.

That was the first time anyone in uniform told him no.

I just didn’t know yet that it would not be the last.

The scans came back clear—no new damage, no reopened incision, just a bruised cheekbone and a lip that would need a couple more stitches. The nurse with the cartoon bandage tattoo stayed while they worked.

“You don’t have to go back with him,” she said quietly while the doctor charted. “You know that, right?”

“I live with my mom,” I said. “He just… came with the mortgage.”

Her mouth twitched like she wanted to smile but couldn’t quite get there. When she wheeled me back from imaging, she tucked a folded piece of paper into my discharge folder, between the instructions about wound care and the list of pain medications.

“If you ever feel unsafe,” she murmured, “this can help more than we can in the ER.”

I didn’t look at it right away. I was too busy pretending I wasn’t humiliated, that I wasn’t the kind of woman who ended up on the floor of a hospital room with a handprint on her face.

But later that night, when the lights were dim and Mrs. Chen snored softly behind the curtain, I slid that paper out.

It was a card for a domestic violence hotline and website. The edges were worn like it had lived in her pocket for a long time.

I stared at it until my eyes blurred.

I’d always thought domestic violence meant broken bones and whispered excuses about “walking into a door.” I didn’t think it counted if you were almost thirty, if the guy hitting you wasn’t even your biological father, if most of the bruises were on your bank account and not just your skin.

But as I lay there with my stitches throbbing and the taste of copper still lingering at the back of my throat, something inside me shifted.

If this wasn’t normal for other families in this hospital, maybe it didn’t have to be normal for mine either.

Let me back up.

Three years earlier, my mom was drowning.

My dad had fought cancer for two years before it finally took him. Even with insurance, the bills stacked up like bad Jenga blocks. Every new envelope that came in the mail felt heavier than the last, like the paper knew it was full of bad news.

Mom was working at the library, trying to keep things afloat. I was juggling two jobs—daytime retail at a big‑box store off the highway, nights and weekends doing freelance graphic design for anyone willing to pay in actual money and not just “exposure.” I still walked past Dad’s old grill on the back porch and expected to see him there with his silly apron and a beer.

But grief doesn’t stop the mortgage company from sending letters.

I’d started getting disability payments after a car accident five years earlier messed up my back. It wasn’t a ton, but it helped. Between that, my jobs, Mom’s paycheck, and what little was left of Dad’s life insurance, we were keeping the lights on and the fridge mostly full.

Barely.

And then Gary arrived.

He came in like some kind of discount savior at Mom’s Thursday night book club. He was someone’s plus‑one, leaning in the kitchen doorway with a craft beer in his hand and a story ready for every topic.

He said he was a successful businessman who’d just moved to our little town because he wanted “a quieter life.” He wore a button‑down shirt that looked expensive if you didn’t know outlet mall tags, and the guys at the club were impressed when he mentioned his Corvette idling in the driveway.

Mom was impressed that he helped stack chairs without being asked.

Six months later, they were married in a small ceremony at the Methodist church, the one with the white steeple and the faded American flag magnet slapped crooked on the refrigerator in the fellowship hall. He promised to “take care of his girls” during the reception, his hand heavy on Mom’s shoulder while I held a plate of Costco sheet cake.

If there were red flags, we treated them like decorative bunting.

When you’re desperate, you get good at pretending red looks like rose gold.

He moved in the day after the wedding with two suitcases and a box of trophies—bowling league plaques, sales awards from dealerships, and that ring he never shut up about.

“Championship ring,” he told anyone who glanced at it. “Won it in 2019. Perfect game in the finals.”

He said it so often I could’ve recited the story in my sleep.

At first, it was little things. Gary said it would be easier if he handled the finances. Mom added him to her bank accounts “for convenience.” He talked her into putting his name on the deed “for tax reasons.” He said my disability checks should go into a shared household account so he could “budget better.”

I was twenty‑six, living in my childhood home, paying rent to my own mother because Gary insisted “adults contribute.” I told myself it was fair.

We were still always broke.

Somehow, the more Gary “managed,” the less there was to go around.

He never seemed to miss an oil change on the Corvette. The tires were always fresh. The bowling league dues were paid on time. Meanwhile, the power bill came with pink highlight more often than it should have.

I started noticing things went missing. Not jewelry or electronics—Gary was smarter than that. It was paperwork.

A medical bill I’d set aside to call about would vanish. Insurance explanations of benefits disappeared. Letters from the disability office never made it out of the mail pile.

“Did you see—” I’d start.

Gary would pat me on the shoulder like I was a confused child.

“I took care of it,” he’d say in that syrupy voice. “You don’t need to worry your pretty little head about boring money stuff, Rihanna. That’s what men are for.”

The condescension was so thick you could’ve poured it over pancakes.

Mrs. Chen from next door—the other Mrs. Chen—tried to warn us.

She was Vietnamese, in her seventies, and made spring rolls that could make you cry they were so good. She’d knock on our back door with a Tupperware container and a look.

“I hear yelling,” she’d say softly to me while Mom was at work. “That man, he has too much noise in him.”

She’d seen him in the backyard punching the siding when the lawnmower wouldn’t start. She watched him put his fist through the drywall by the patio door and then hand me a spackle knife like it was my mess to fix.

“He is the kind who likes control,” she murmured the first time I helped her carry groceries. “Control and secrets.”

But we were already in too deep for warnings to land.

By the time you realize someone’s been quietly moving furniture around in your life, you’ve already stubbed your toe on everything that used to feel familiar.

The night my appendix decided it had had enough of this world, I came home from a double shift at the store bent forward, hugging my stomach.

Mom wanted to drive me straight to the ER. Gary complained about the gas, then complained again about the co‑pay while I lay under bright lights with tears leaking out the corners of my eyes.

“You’re lucky you came in when you did,” the surgeon told me afterward. “Another two hours and we’d be having a much scarier conversation.”

Lucky.

It’s funny how one word can take on such a twisted shape in your head.

While I was still half under anesthesia, Gary was pacing the waiting room, telling anyone who would listen that hospital prices were a scam and people “these days” liked drama.

Three days later, he walked into my room with a printout of the estimated bill and that ring shining on his finger.

“You better start earning your keep,” he said.

Then came the slap, the tiles, the cops, the card from the nurse.

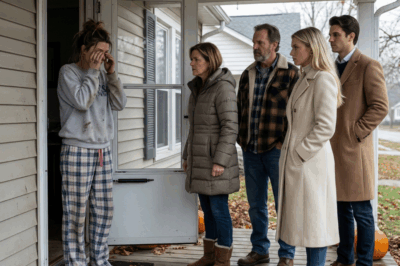

After they cleared me to go home, Mom came to pick me up alone.

“Where’s Gary?” I asked as I eased myself into the passenger seat, clutching the little pillow they’d given me to hold against my stitches.

“He had to work,” she said quickly. “He feels terrible about what happened. It was just a misunderstanding.”

An orderly wheeled past us, humming Sinatra under his breath. A car two rows over had a faded U.S. flag bumper sticker peeling off the corner.

“Mom,” I said, “he hit me.”

Her hands tightened on the steering wheel.

“He’s under a lot of pressure,” she whispered. “The medical bills, the house, the car payment… You know how he gets when he’s stressed.”

“That’s the problem,” I said. “I do know.”

She didn’t answer. She just pulled out of the hospital lot and onto the road home, eyes fixed straight ahead, shoulders curled inward like she was trying to make herself smaller than her seatbelt.

I slid my hand into my bag and felt for the card.

That night, propped up on my own couch with the curtains drawn, I went to the website listed on it.

I thought I’d read a couple of paragraphs and roll my eyes. Instead, I sat there until after midnight clicking through story after story that felt uncomfortably familiar.

Financial control. Isolation. Intimidation without leaving visible marks. Explosive “rages” that were always somehow the victim’s fault.

There was even a checklist.

Does your partner control access to money? Yes.

Do they make you feel like you’re crazy when you question them about bills? Yes.

Do they belittle your work, your contribution, your health? Yes, yes, yes.

By the time I shut my laptop, my incisions hurt from tension. My hands were shaking so badly I almost dropped my water.

I told myself I was overreacting.

But a small, stubborn part of me had already made a promise on that hospital floor.

If I ever got off those tiles and back on my feet, Gary wasn’t going to be the only one writing the rules anymore.

Two weeks into my supposed “recovery,” Gary made his first big mistake.

He left me alone with his secrets.

He’d been talking for months about a bowling tournament in Atlantic City, the kind of three‑day event he claimed could “put him on the map” if he won.

“Entry fees aren’t cheap,” he’d told my mom as he slid cash out of the emergency envelope she kept in the kitchen cabinet. “But it’s an investment. I win this, we’re cushioned for a year.”

He kissed her on the forehead with one hand while the other tucked three hundred dollars into his wallet.

Mom had one of her “bad days” the morning he left, curled up in bed with stomach cramps and a headache.

“Must be a bug,” Gary said, dropping a handful of vitamins into her palm. “These will help.”

I watched her swallow them with orange juice and a small wince. She’d been getting sicker and sicker over the last year—mysterious fatigue, brain fog, stomach issues. Gary said it was stress.

I wasn’t sure.

When the door closed behind him and the Corvette’s engine faded down the street, the house felt different.

Lighter. But also full of ghosts.

Gary’s home office had always been off‑limits. Dark wood door. New lock he’d installed himself.

“Important business documents in there,” he’d told me once when I tried to borrow a stapler. “Can’t have people snooping around. You understand.”

I didn’t. Not really. But I did understand how YouTube worked.

Pain medication courage is a real thing. So is the quiet fury that builds when you’ve tasted your own blood on a hospital floor.

I waited until Mom fell into a restless sleep, then grabbed a bobby pin and my phone.

Turns out those fancy locks Gary bragged about buying weren’t that impressive.

The door clicked open in less than a minute.

The office smelled like stale coffee and cheap cologne. The blinds were half‑drawn, throwing slatted light across a crowded desk.

On the wall, above rows of binders, hung a framed photo of Gary holding up his bowling championship ring, grinning like someone who’d never heard the word consequence.

On the desk, his laptop sat open, the screen saver bouncing a little logo from corner to corner.

“Seriously,” I muttered. “You don’t even password‑lock this?”

He didn’t.

What I found in that room changed everything.

And I don’t just mean my opinion of Gary.

I mean the entire trajectory of our lives.

I started with the file cabinet.

The top drawer held bills. Not ours. Bills from Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware. Names I didn’t recognize at first. Then one I did—from a Facebook friend suggestion I’d seen months earlier and ignored.

Barbara.

The second drawer was worse.

Four marriage certificates, carefully filed.

Gary Peterson and Barbara King — Franklin County, Ohio.

Gary Peterson and Darlene Cooper — Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

Gary Peterson and Susan Miller — Camden County, New Jersey.

Gary Peterson and Margaret Wright — Newcastle County, Delaware.

He’d told Mom he’d been married twice before. The paperwork said otherwise. Every divorce file had a copy of a restraining order tucked behind it.

He had a system: stay two to four years, then move at least one state over.

My stomach rolled.

A shoe box on the bottom shelf of the closet held credit card statements.

All of them in my name.

Cards I’d never applied for. Accounts I’d never used. Balances I would never have run up.

I flipped through them, my pulse roaring in my ears.

Late fees. Cash advances. Charges at electronics stores, car repair shops, high‑end bowling pro shops. Minimum payments made just often enough to keep the lines alive.

I pulled out my phone and snapped pictures of every page.

The next file folder made my vision go tunnel‑dark.

Three life insurance policies.

All on my mother.

All taken out in the last year.

All with Gary Peterson as the sole beneficiary.

Total payout if she died: $2,000,000.

She had never been worth that much money alive in his eyes.

But dead?

Dead, she was an investment.

I found the bottles of “vitamins” in the bottom desk drawer, the ones Gary ordered online and insisted she take instead of the generic multivitamins from Target.

I lined them up on the desk and photographed each label, front and back.

My hands shook so hard that some of the pictures came out blurry.

What I saw was horrifying.

What I didn’t see yet was that his real empire wasn’t built in paper files.

It was built in pixels.

Gary’s laptop was still logged into his email.

He wasn’t big on cyber‑security, apparently.

The inbox was a horror show.

There were threads with women from dating sites where his profile described him as a widower entrepreneur with “no kids” looking for “a traditional woman who knows how to appreciate a real man.”

Mom wasn’t dead, but he was already workshopping his future.

There were emails to a lawyer about selling our house—Dad’s house, the one he’d paid off with his life insurance so we’d always have somewhere to land.

“Client would like to know,” one email read, “what happens if spouse becomes mentally incompetent. Also questions about power of attorney and ability to make medical decisions if spouse is incapacitated.”

There were drafts of messages where he talked about Mom’s “declining mental state,” about how she was “forgetful, confused, not herself anymore.”

The browser history made my stomach ice over.

Searches about dangerous combinations of supplements. About ways to make someone look sick without obvious markers. About how certain substances could mimic natural organ failure.

Searches about undetectable methods.

And then, as if my brain needed one more hit, I found the disability portal.

He’d been filing claims in my name.

Extra benefits I had never seen, rerouted to accounts I didn’t know existed.

Loans taken out in my name, my Social Security number typed neatly into digital forms.

My credit, which I’d been slowly rebuilding for years after some dumb twenty‑one‑year‑old decisions, was shredded.

I sat there in his office chair, surrounded by his trophies and fake certificates, and let the reality sink in.

Gary didn’t just hit me in that hospital room.

He’d been hitting us financially, medically, legally, every way that counted, for years.

The slap was just the first time everyone else could see it.

I didn’t cry. Not yet.

Instead, I did something he never expected.

I started taking notes.

The first woman I found was Darlene.

Her profile picture on Facebook showed her holding a little chalkboard sign that read SURVIVED AND THRIVING, standing in front of a 5K finish line with a medal around her neck.

Her account was locked down tight. Private. Guarded.

I sent her a message anyway.

“Hi,” I wrote. “I think we have a Gary in common.”

I attached a photo I’d snapped from the office wall—Gary at a bowling alley, holding up his ring.

For a minute, nothing happened.

I paced the hallway, checking to make sure Mom was still asleep. Mrs. Chen next door watered her rosebushes and watched our windows like they were a TV show.

My phone buzzed.

He got another.

That was all Darlene wrote at first.

Then, a second message.

“Call me if you’re safe to talk.”

We talked for three hours.

Her story was my story with slightly different furniture.

The whirlwind romance. The promises to “take care of everything.” The sudden insistence on handling all the money. The way her friends drifted away after Gary kept picking fights at gatherings. The mysterious illnesses.

“I never proved it,” she said, her voice steady but brittle. “But I caught him once in the kitchen, putting something in my coffee. He said it was a sweetener. I don’t take sweetener.”

She’d fought him in court and barely kept her house. She’d gotten a restraining order by keeping every receipt, every email, every text.

“You have to document everything,” she told me. “Men like Gary don’t stop until someone bigger tells them to. And they don’t believe you unless you have proof lined up like a parade.”

Darlene had stayed in touch with Barbara and Margaret. Susan had died.

“Heart attack,” Darlene said. “That’s what the paper said. But Gary had policies on her, too. Worth a lot less than what he’s got on your mom, from what you’re telling me.”

Within a week, we had a group chat.

We called ourselves the Gary Survivors Club, which sounded almost funny if you forgot for a second why it existed.

Barbara had become an advocate for domestic violence survivors.

Margaret worked as a paralegal and knew exactly which kind of evidence stood up in court.

Darlene was the archivist. She’d kept everything. Fifteen years’ worth of proof that Gary had a pattern.

As we compared stories, timelines, and bank statements, the picture got sharper.

Gary wasn’t messy. He was methodical.

He found women who were grieving, lonely, or financially stretched.

He love‑bombed them with attention, then isolated them.

He wrapped his hands around their money, then their health.

If they caught on too fast, he smeared them as unstable and cut his losses.

If they stayed quiet long enough, he set up policies and waited.

The number that kept ranking in my head wasn’t his stupid 2019 bowling score.

It was $2,000,000.

That was what my mother was worth to him if she stopped breathing.

And she was getting weaker every day.

Mrs. Chen next door noticed it too.

“She’s smaller,” she told me one afternoon as we sat on her back porch, spring rolls cooling between us. “Your mother. She looks like a shirt that’s been washed too many times.”

Her daughter Amy was a pharmacist at the big chain drugstore on Main.

I showed Amy photos of the vitamins I’d taken from Gary’s office.

Her face went pale.

“I can’t technically give you medical advice about specific brands without seeing the bottles in person,” she said carefully, “but… some of these combinations? In high doses? Over time they can absolutely cause fatigue, confusion, nausea. In extreme cases, organ damage.”

“Like liver failure? Kidney failure?” I asked.

She nodded once.

“If someone didn’t know what they were taking,” she added, “it could just look like they were getting sicker. Especially if their caregiver was the one describing the symptoms to the doctor.”

I swallowed hard.

“Can you put that in writing?”

“Not yet,” she said. “But if law enforcement gets involved, yes. I can testify to what those substances do.”

The promise in her voice steadied me more than any pain pill.

It wasn’t all in my head.

It was in my mother’s bloodstream.

From that day on, I stopped waiting for Gary to get better.

I started waiting for him to slip.

I bought tiny cameras online, the kind that looked like phone chargers and smoke detectors and digital clocks. Thank you, late‑night internet.

I hid them in the kitchen, the living room, the hallway outside Gary’s office, even in my mom’s bedroom, angled toward the dresser where he kept her pills and vitamins.

Every time he shook tablets into his hand and carried them to her with a glass of water, the cameras saw.

Every time he told her, “Just take these, you’re not thinking straight lately,” the microphones heard.

In the living room, a camera disguised as a USB charger caught something else.

Gary practicing.

He’d stand in front of the mirror, rehearsing conversations he thought he’d have someday.

“I did everything for her,” he’d say, eyes glistening on command. “She was just so sick. I can’t believe she’s gone.”

He’d fake‑sob and then stop, evaluating his reflection.

“Too much?” he’d mutter. “Maybe quieter. They like quiet grief.”

Sometimes he practiced phone calls.

“Officer, I’m just beside myself. My wife… she collapsed. She’s been so confused lately. Her doctor thinks it might be early dementia.”

Sometimes he practiced flirting.

His laptop, once we had Tyler involved, revealed browser tabs full of dating profiles he’d never bothered to fully delete.

Tyler was Big Eddie’s nephew.

If Gary was proud of anyone besides himself, it was Big Eddie—three hundred pounds of bowling legend and retired truck driver who ran half the league.

Gary had hit up the league’s unofficial loan fund, convincing six guys to invest their retirement savings in a “sure‑thing” business opportunity.

He’d promised to triple their money in a year.

When payments stopped and excuses started, they brought in Tyler.

Tyler worked in IT security and had, in his words, “a low tolerance for clowns.”

He was the one who discovered that Gary used the same passwords for everything.

GaryBS300.

Because of course he did.

Within a week, Tyler had mapped out a digital spiderweb of Gary’s scams in four states. Fake LLCs. Phony investment portfolios. Email chains where Gary promised astronomical returns in suspiciously vague ventures.

He traced more than $19,500 in “investments” just from the bowling league alone.

Victims from other towns, other leagues, other states started popping up as Tyler dug through public records and complaint boards.

Gary had left a trail of digital oil slicks wherever he went.

All we had to do now was strike the match.

Gary’s second big mistake came in a manila envelope.

It was a Tuesday evening. Mom was on the couch under a blanket, her skin sallow, her eyes cloudy. I sat at the kitchen table, pretending to scroll through job listings on my laptop.

Gary walked in whistling, tossed his keys in the bowl by the door, and dropped the envelope in front of me.

“Big day,” he said. “Lawyer drew up some paperwork for your mom. Just a formality.”

I opened it.

Power of attorney. Financial and medical. Full control over her accounts, her treatment, her decisions.

He’d highlighted the signature line.

“I figured we could just have her sign tonight,” he said. “Get you to witness it. Keeps it all in the family. Judges love that.”

Mom’s hand trembled when she reached for the pen.

“Do I have to?” she whispered.

Gary flashed the patient, indulgent smile he reserved for outsiders and police officers.

“It’s just in case, honey,” he said. “You’ve been so foggy lately. We need to be prepared. You wouldn’t want Rihanna to be burdened with all this stuff if something happened, would you?”

My heart hammered against my stitches.

I thought of the searches on his laptop. The policies. The vitamins lined up like soldiers in our hallway camera feed.

I thought of $2,000,000.

“Gary,” I said, forcing my voice to wobble just enough to sound harmless, “shouldn’t the lawyer be here for something this big? I mean, you’re always telling me how important it is to do things by the book.”

He froze.

He couldn’t argue without looking suspicious.

He also couldn’t admit he’d hoped to slide this through quietly at our kitchen table.

His eyes narrowed.

“Of course,” he said slowly. “I was just trying to save us a trip. I’ll call and set up an appointment. Next week.”

Seven days.

He thought he’d just kicked the ball down the road.

In reality, he’d started the countdown.

I texted Darlene from the bathroom.

He’s pushing POA. Wants full control. Cruise booked in 10 days. Just him and Mom. He told an aunt I’d be staying with her—she has no idea.

My phone buzzed.

Call the hotline. Then call the cops. Then call us. In that order.

The next day, Adult Protective Services opened a file on my mother.

The day after that, a detective from the financial crimes unit called to set up a meeting.

By the end of the week, the FBI was in a conference room with Tyler and three members of the Gary Survivors Club, looking at a wall of evidence and saying words like pattern and multi‑state and probable cause.

There are moments when your life feels like a TV show.

For me, that moment was standing in a government office, watching my mother’s name written on a whiteboard under the label POTENTIAL HARM.

Seven days.

That’s how long Gary thought he had to legally own her life.

That’s exactly how long it took us to arrange for him to lose his freedom instead.

The night before the scheduled signing at the lawyer’s office, Gary went to the bowling alley for the league championship playoffs.

He wore his usual uniform—league shirt stretched tight across his stomach, lucky wrist brace, polished ring.

“Don’t wait up,” he called over his shoulder. “Champions stay late.”

He kissed my mom on the forehead and, as he straightened, tipped a small envelope of powder into her evening tea behind her back.

The camera in the kitchen clock saw it.

So did the FBI agent watching the live feed in an unmarked SUV down the block.

At 7 p.m., our house turned into a crime show.

Two marked police cruisers pulled up first, lights off. Then an unmarked sedan. Then an ambulance and a car from Adult Protective Services.

The doorbell rang.

“Ms. Hester?” the social worker said when Mom shuffled to the door. “We’re here to make sure you’re safe.”

She blinked, confused.

“Is Gary in trouble?” she asked.

“Not yet,” the detective behind the social worker said. “But he’s about to be.”

They escorted her to the ambulance for a full medical work‑up.

The vitamins and powders went into evidence bags.

Gary’s office got flipped—computers seized, files boxed, the framed photo of him holding up that ring wrapped carefully in brown paper.

Next door, Mrs. Chen stood on her lawn in a housecoat, filming everything on her phone and providing rapid‑fire commentary in Vietnamese to relatives on FaceTime.

“He thinks he is big man,” she said, gesturing as agents carted out boxes. “Now he is small box.”

At the bowling alley, the FBI waited until Gary lined up for a crucial frame.

He did his whole routine—two practice swings, three steps, release. The ball spun down the lane in a perfect curve.

Strike.

He turned, grinning, arms wide, ready for applause.

Instead, two men with badges stepped in front of him.

“Gary Peterson?” one asked.

Gary puffed up. “Depends who’s asking.”

“Special Agent Collins, FBI,” the man said, flipping open his ID. “You’re under arrest for interstate fraud, identity theft, and suspected financial exploitation. You need to put your hands behind your back.”

A hush fell over the lanes.

Someone’s kid dropped a slice of pizza.

Big Eddie stared for a beat, then started a slow clap.

It spread down the row—one set of hands, then another, then the whole league, clapping as Gary’s championship ring flashed one last time under the cosmic bowling lights while the cuffs clicked shut over his wrists.

A teenager at the snack bar caught the whole thing on his phone.

By midnight, the video was on Facebook.

By morning, it was on the local news.

The charges stacked up fast.

The substances in Mom’s vitamins tested positive for combinations that, over time, could cause organ damage and cognitive decline.

The life insurance policies showed clear motive.

The surveillance footage showed him tampering with her drinks and practicing his grieving widower routine.

Tyler’s digital evidence laid out years of fraud—fake investments, stolen disability payments, forged signatures.

Adult Protective Services documented Mom’s sudden health decline after Gary moved in.

The Gary Survivors Club provided a pattern.

And Mrs. Chen, both of them, were more than happy to talk.

My hospital roommate, Mrs. Chen with the hip replacement, called the detective after seeing Gary’s mug shot on the six‑o‑clock news.

“I told you he was a bowling league reject,” she said. “You should put that ring in a museum for fools.”

The other Mrs. Chen, my neighbor, testified about the yelling, the wall punching, the vitamins, the way Mom seemed to shrink after each “argument.”

Amy explained exactly what those supplements could do when taken at the doses Gary pushed.

Darlene, Barbara, and Margaret each flew in once to give sworn statements.

The FBI set up a dedicated tip line.

They got over two hundred calls in the first week.

As one agent put it, “We could make a whole conference out of this guy’s bad decisions.”

Someone—Tyler, obviously—bought the domain GaryCamAlert dot com.

By the time Gary’s arraignment rolled around, that website held timelines, public records, links to news articles from four different states, and a big red banner urging other potential victims to come forward.

It crashed three times from traffic.

The local ABC affiliate ran a segment titled LOCAL MAN ARRESTED IN MULTI‑STATE FRAUD AND ELDER ABUSE SCHEME. It was catchy, but if you’d lived it, it still felt like an understatement.

Gary’s car dealership fired him via text while he was still in county.

“Your services are no longer required,” it read. “Effective immediately.”

The owner went on the news to say Gary had been their worst salesman anyway.

“He talked more than he listened,” he said. “That’s a bad combo in sales and in life.”

Women Gary had been messaging on dating apps started posting screenshots.

“Is this your fiancé?” one wrote under a mug shot screenshot. “Because he asked me for a loan for his ‘sick mom’ last month.”

His mother had been dead for fifteen years.

My favorite moment came a couple of weeks after his arrest.

A local station was doing a follow‑up story in front of our house. The reporter stood on the lawn, microphone in hand, talking about the upcoming trial and the growing number of victims.

Behind him, in the driveway, a tow truck backed up to the Corvette.

The repo guy shrugged at the camera.

“Payments are three months behind,” he said. “Car belongs to the bank now.”

They loaded Gary’s prized possession onto the flatbed while the reporter tried to keep a straight face.

The anchor back in the studio failed completely.

“He may have to work on his exit strategy,” she said between laughs.

The only thing missing from that shot was the ring.

It was already in an evidence bag.

Mom’s health turned a corner once she was off Gary’s pills.

Within a week of being in the hospital, actually treated instead of slowly poisoned, color crept back into her cheeks. The fog in her eyes lifted.

“The labs are better than I’d expect for someone her age,” her doctor told me after reviewing the tests. “Another month on those supplements, though, and we might be having a very different conversation.”

Mom cried when she realized what had been happening.

Not quiet, movie‑pretty tears.

Ugly ones.

“Did I really not see it?” she asked me one night, clutching my hand in her hospital room while the TV flickered quietly with some crime show that suddenly felt too on‑the‑nose.

“You saw pieces,” I said. “He made sure you never saw the whole picture.”

“I defended him,” she whispered. “To you. To the police. I stood there and made excuses while you were on the floor.”

“You were surviving,” I said. “Just like I was.”

She shook her head.

“I thought if I just stayed quiet, if I just didn’t make waves, it would get better.”

“That’s what he wanted you to think,” I said. “Silence was part of his plan.”

We let the crime show play out in the background, some actor in a suit making a closing argument.

“We’re not quiet anymore,” I added.

That was the real victory, long before the jury ever filed into a box.

The trial itself felt almost anticlimactic after the months of build‑up.

The prosecutor, Patricia Jensen, wore pearls and carried her files in a battered leather briefcase that looked older than I was.

Her voice was soft until it wasn’t.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” she said in her opening, “this case is about a man who learned exactly how much people were worth on paper and decided that was more important than what they were worth as human beings.”

Gary’s lawyer tried to argue stress. Tried to argue misunderstanding. Tried, in a move so ironic it could’ve powered a small city, to argue that Gary had mental competency issues of his own.

Patricia dismantled every angle.

She walked the jury through the paper evidence—the policies, the forged signatures, the credit cards in my name.

She showed them the video of Gary slipping powder into Mom’s tea.

She played clips of him practicing his grieving act in the living room mirror.

She called Tyler to the stand to explain, in simple language, exactly how Gary had used the same password to wreck lives in four states.

She put the ring on the evidence table, still in its bag.

“This ring is the only championship Mr. Peterson ever truly earned,” she said. “Not for his bowling. For how many people he managed to hurt before they finally compared notes.”

Gary glared at her like he could burn holes in her blazer.

It didn’t work.

The jury deliberated for less than two hours.

That included lunch.

Guilty on fraud. Guilty on identity theft. Guilty on financial exploitation of a vulnerable adult. Guilty on assault. Guilty on attempted harm.

The judge—a woman with gray hair pulled back in a bun and a patience level far below zero for theatrics—let Gary speak before sentencing.

He tried to paint himself as a misunderstood provider.

“I only ever wanted to take care of my family,” he said, voice cracking right on cue. “I made some mistakes, but I’m not a monster.”

“Mr. Peterson,” the judge said, cutting him off, “the only person you’ve consistently taken care of is yourself, and you didn’t even do that particularly well.”

She sentenced him to fifteen years.

No Corvette. No bowling league. No late‑night rehearsals in his living room mirror.

Just time.

A lot of it.

As the deputies led him away, the ring sat under fluorescent lights in its plastic bag.

For years, it had been his favorite symbol of power.

Now it was just Exhibit 47.

The civil suits came next.

The Gary Survivors Club joined forces with a couple of furious bowlers and a very motivated financial crimes unit.

Between restitution orders and settlements, the numbers on the whiteboard started shifting.

It would never be enough to erase the damage he’d done.

But it was enough to get Mom’s house back in her name, free and clear, plus a cushion.

The day the new deed arrived in the mail, Mom framed it and hung it where Gary’s bowling photo used to be.

“That’s my trophy,” she said, tapping the glass.

We turned Gary’s old office into a craft room.

The wall where his framed certificates once hung now holds shelves of fabric and yarn.

Mom makes quilts for the women’s shelter in town. Every stitch is another inch between her and the woman who used to sit in that room thinking she was crazy for feeling scared.

I got a job at a victim advocacy center downtown.

My first week there, I walked into the break room and almost dropped my coffee.

Nurse Rebecca—the one with the cartoon bandage tattoo, who’d slipped me the hotline card—was stirring sugar into her mug.

“You work here?” I blurted.

She blinked, then smiled.

“I knew you looked familiar,” she said. “Appendectomy, right? Stepdad with the ring?”

“That’s one way to describe him,” I said.

“I followed your case,” she admitted. “On the news. I was hoping you got out.”

“I did,” I said. “Because you handed me a piece of paper when no one else was looking.”

We hugged in the middle of the break room, the fridge humming beside us, a little magnet of the American flag holding up a flyer for a support group.

Full circle, I thought.

The Gary Survivors Club still meets once a month.

We pick a different brunch spot every time, but we always ask for a table by the window.

Darlene usually gets there first and orders bottomless mimosas.

By her third glass, she’s loud and laughing and telling the story of how Gary claimed to be allergic to gluten but used to sneak dinner rolls into his pockets like contraband.

Barbara brings pamphlets from whatever conference she just attended and slips them into my bag.

Margaret updates us on legal reforms.

“Some states are finally taking financial abuse as seriously as physical,” she says. “About time.”

We swap stories that used to make us cry and now make us roll our eyes.

How Gary said he was a wine connoisseur but only bought bottles from gas stations.

How he’d brag to anyone who’d listen about that ring.

“How’s he doing without it?” Darlene asked once.

I thought of the evidence locker, the inventory number, the way the bag crinkled when the clerk handed it to me after the trial.

Victims can choose what happens to personal items after a case closes.

I didn’t want to keep it.

But I didn’t want to pretend it never existed either.

So I took the ring to a local artist who did metalwork.

“Can you melt this down?” I asked. “Turn it into something else?”

A month later, I picked up a small pendant.

Simple. No engraving. No bragging rights.

Just a thin band of gold shaped into a tiny, imperfect circle.

I don’t wear it every day.

But sometimes, when I’m sitting across from a client at the center—a woman staring at her hands, or a man apologizing for crying, or a teenager insisting their bruises are “no big deal”—I feel the weight of it against my collarbone.

“This is not the end of your story,” I tell them.

I know, because it wasn’t the end of mine.

Mrs. Chen next door has basically adopted us.

Every Sunday she brings over spring rolls and gossip.

She and Mom play mah‑jong at the dining table where Gary once tried to slide power‑of‑attorney papers across the wood.

They talk about neighborhood pets and TV dramas and whether the new mayor really knows what he’s doing.

Sometimes, when they think I’m not listening, they talk about fear.

“How did you stay so long?” Mrs. Chen asked her once.

“I thought leaving would be harder than staying,” Mom said. “I was wrong.”

The other Mrs. Chen—the hospital one—sent a card a few months after the trial.

Inside, in shaky handwriting, she’d written, I’m proud of you for standing up to that bowling‑ball‑headed fool.

I keep it on my dresser.

On bad days, I look at it and remember that even when I felt completely alone, strangers saw what was happening.

They pressed call buttons. They wrote cards. They slid paper into folders.

They reminded me that what Gary called “family business” had a different name when the rest of the world looked at it.

Crime.

Every once in a while, I still dream about the hospital floor.

In the dream, the tiles are freezing. My lip is bleeding. The machines are screaming. Gary’s shadow stretches over me.

But then the scene changes.

Nurses step between us.

Police walk in.

A nurse’s hand slips a card into my file.

And over Gary’s shoulder, the tiny plastic flag on the IV pole flutters in the air‑conditioning.

Not as decoration.

As a reminder.

This is a place where people are supposed to be safe.

That’s what I tell the people who come into my office now.

I don’t sugarcoat what it takes to leave.

It’s scary. It’s messy. It’s unfair that the person hurting you usually has more power, more money, more practice.

But I also tell them this: the moment someone decides your body, your wallet, or your life belongs to them is the moment you’re allowed to start fighting back.

Maybe that fight starts with a phone call.

Maybe it starts with a card tucked into a discharge folder.

Maybe it starts with you lying on a cold hospital floor, tasting metal and fear, and realizing this cannot be the last chapter.

For me, it started with a slap and a ring.

It ended—well, really, it began—with a gavel, a sentence, and a room full of people who finally believed me.

Gary thought he was writing a story about how much control one man could have.

Turns out, he was just the prologue to the story about how fast that control disappears when the truth finally makes it onto the record.

A year after the sentencing, I got a letter I almost threw away.

It was addressed to me in careful, old‑fashioned handwriting, the kind that belongs on recipe cards and Christmas envelopes, not plain white business paper. The return address was a small town in Indiana I’d never heard of. I almost tossed it into the junk pile with coupon books and cable flyers.

Then I saw the last name on the corner.

Peterson.

For a second, my stomach clenched. Rationally, I knew Gary couldn’t send anything without it being inspected. Emotionally, my body still reacted like he might walk through the door any second and start complaining about the thermostat.

I opened it at the kitchen table, the afternoon light slanting across the quilt Mom was working on.

Inside was a single sheet of lined paper and a photograph.

The photo showed an elderly woman in a wheelchair, wrapped in a cardigan with little embroidered cardinals on it. Her hair was thin, her eyes sharp.

The letter began, My name is Helen Peterson. I’m Gary’s mother.

I read it twice before I said anything.

“She’s real?” Mom asked when I slid it across the table. “I thought she was part of one of his stories.”

“She’s very real,” I said. “And apparently not impressed with her son.”

Helen wrote about watching the news one night, seeing Gary’s mug shot flash on the screen between a weather report and a piece about a local Fourth of July parade. She wrote about calling the tip line to confirm it was him. About the relief and shame that tangled in her chest when she realized other people finally knew what he was.

“He always had two sides,” she wrote. “The side he showed neighbors and teachers and boys at the lanes. And the side we got when the door closed. I’m sorry you had to meet that side too.”

She didn’t ask us to forgive him.

She didn’t ask for updates or favors.

She just wanted us to know she believed us.

At the bottom, there was a postscript.

P.S. He lied about me having medical bills. Please tell the woman he asked for money that I’m fine and that my doctor visits are covered by Medicare.

I laughed, then cried.

Mom folded the letter carefully.

“Keep it,” she said. “Not for him. For us.”

We tucked it into the same file where I kept the card from Mrs. Chen and the print‑out of the original news article. Not as trophies. As markers.

Proof that we weren’t crazy. Proof that the story continued even after the credits rolled.

Work at the center turned out to be its own kind of education.

I thought my experience had prepared me for anything.

It hadn’t.

There was the woman who came in with perfectly done nails and a designer bag, insisting she just needed “a little advice” about a boyfriend who’d taken her car keys. By the end of the interview, we’d scheduled an emergency safety plan and contacted a shelter.

There was the retired firefighter whose grown son had emptied his bank account “by accident” three times.

There was the teenage boy who said he was “fine” with a bruise blooming purple under one eye, then dissolved when we told him hurting someone because they’re queer isn’t “just how families are.”

Patterns echoed in different accents, different zip codes, different ages.

Control. Isolation. Money as leash.

Sometimes, when clients hesitated to name what was happening to them, I told pieces of my story.

“I went through something similar with my stepfather,” I would say. “He thought because he paid some bills, he owned me.”

They always looked up at that.

“Did anyone believe you?” one woman asked, knuckles white around the handle of her purse.

“Not at first,” I said. “But once one person did, it got easier for others to see it.”

“What changed?” she pressed.

“A nurse pressed a call button,” I said. “An eighty‑three‑year‑old lady pushed hers and wouldn’t let go. A cop walked into a hospital room and didn’t let ‘family business’ be the end of the story. Sometimes that’s all it takes. One person refusing to look away.”

I didn’t always mention the ring, but I always thought about it.

How something meant to show off a perfect game had become the sharp edge that split my lip and opened everything else.

On the anniversary of Gary’s arrest, the bowling alley hosted a fundraiser.

It wasn’t our idea.

Big Eddie called me a month earlier, his voice booming through my phone like we were still sharing hospital walls.

“Got a plan, kid,” he said. “We’re doing a charity tournament. All proceeds to the victim center and the shelter. We’d like you and your ma to come down, say a few words if you’re up to it.”

I pictured the lanes—polished wood, neon signs for beer specials, the faint smell of shoe spray and old fries. I pictured Gary in his league shirt, holding court between frames.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Totally your call,” Eddie said. “No pressure. We just figure if that place was where everybody watched him go down, maybe it oughta be where something decent starts too.”

He had a point.

Mom surprised me by saying yes first.

“I don’t want to be scared of a building,” she said, straightening the collar of her blouse in the mirror. “He took enough from us. He doesn’t get to keep the bowling alley too.”

When we walked in that Saturday afternoon, people looked over.

Not with pity, exactly. More like recognition.

There were banners up along the back wall.

STRIKE OUT ABUSE.

BOWL FOR BETTER.

Someone had gotten ambitious with clip art.

Eddie met us at the door, enfolding Mom in a hug that lifted her half off her feet.

“You look good, Marie,” he said, stepping back. “Way better than last time I saw you.”

“Not hard to beat,” she said dryly.

He laughed, then sobered.

“Seriously. If this is too much at any point, you tell me. We’ll whisk you right out the back, paparazzi‑style.”

“There are no paparazzi,” I said.

“You never know,” he said. “This town goes wild for a slow news week.”

He wasn’t wrong. A local station had a camera set up by lane twelve, capturing kids in matching t‑shirts and retired teachers lacing up rental shoes.

When they called me to the small podium by the snack bar, my heart did its old familiar stutter.

I could walk into a courtroom, into a support group, into a shelter without blinking.

A bowling alley still made my muscles tense.

I took a breath, felt the little pendant brush my collarbone, and stepped up anyway.

“Most of you knew Gary as a league member,” I said. “Some of you loaned him money. Some of you watched him chase a perfect score. My family knew a different version of him.”

I didn’t list his crimes.

They’d all seen the news.

Instead, I talked about the nurse.

The two Mrs. Chens.

The way a small community could either look away from shouting next door or lean in and knock.

“Abuse doesn’t always look like what you see in movies,” I said. “Sometimes it looks like someone insisting they handle the bills. Sometimes it looks like ‘vitamins’ that make you sicker. Sometimes it looks like jokes that happen a little too often and land a little too hard.”

I gave them the hotline number.

I asked them to put it in their phones.

“Not because you’ll necessarily need it yourself,” I said, “but because someone you know might. And it’s easier to make a call when a friend is standing next to you.”

When I stepped back, people clapped.

Not the slow clap they’d given Gary on his way out.

Something warmer.

Afterward, a woman in a league shirt came up to me, eyes wet.

“I used to think if my husband didn’t hit me, it didn’t count,” she said. “But the way you described the money stuff? The way you talked about making you feel crazy? That’s… that’s my life.”

I handed her a card.

“It doesn’t have to stay that way,” I said.

As she walked away, Eddie sidled up next to me, arms crossed.

“Not bad, kid,” he said. “You ever get tired of that center job, you could run motivational talks at the lanes.”

“I’ll stick with the center,” I said.

He nodded toward lane seven.

A little girl with pigtails was dancing after knocking down three pins.

“Good,” he said. “We need you there more.”

Life didn’t turn magically perfect after the trial.

Money was still tight sometimes.

Grief still snuck up on us—in the grocery store when I passed Dad’s favorite brand of barbecue sauce, at the hardware aisle when I saw the brand of spackle Gary made me use on his wall holes.

Trust was a muscle I had to rebuild slowly.

Dating, for a long time, was out of the question.

“How do you even know?” I asked Barbara once over pancakes at a diner. “How do you know the next person isn’t just another Gary with better hair?”

“You don’t,” she said. “You just know yourself better. That’s the difference.”

She cut her pancake into neat squares.

“You know what your lines are now,” she continued. “You know what makes your stomach twist. You know what silence feels like when it’s safe and when it’s dangerous.”

“When someone says they’ll handle the money?” I said.

She snorted.

“First date red flag,” she said. “Right up there with being rude to waitstaff and having nothing good to say about any exes.”

The first time I gave someone my number after all of it, my hand shook.

He was a social worker from another agency, kind eyes, nervous smile, the kind of man who listened more than he talked.

On our third date, sitting on a park bench watching kids fly kites, I told him about the hospital floor.

He didn’t flinch.

He didn’t offer to fix it.

He just sat there, letting the breeze carry our words away and asked, “What do you need when those memories feel loud?”

It was such a simple question.

I realized then that Gary’s voice still lived rent‑free in my head more often than I liked.

But it was getting crowded out.

By nurses, by neighbors, by ex‑wives and bowlers and social workers and Mrs. Chens.

By my own.

Two years after the trial, I was asked to testify at the state Capitol.

There was a bill on the floor that would increase penalties for financial abuse of vulnerable adults and expand the definition of “vulnerable” to include people in medically dependent relationships.

The sponsors wanted “survivor voices.”

I almost said no.

Courthouses, bowling alleys, now government buildings. My trauma bingo card was getting full.

Mom squeezed my hand.

“If you don’t want to, we can stay home and watch it on TV,” she said. “You’ve already done more than enough.”

“I know,” I said.

I thought about the number on the insurance form.

$2,000,000.

That had been my mother’s potential payout.

Somewhere, there was another family with a different number on a different policy and a different Gary flipping through pages.

“I want to,” I said. “I just don’t want to want to.”

She smiled.

“That’s usually how the important things feel,” she said.

The hearing room was smaller than I expected.

No soaring ceilings, no dramatic echo. Just rows of chairs, a long table with microphones, and a line of people clutching notes.

I listened as others spoke—an elderly man whose nephew had emptied his accounts, a nurse who’d seen too many “falls” that didn’t look accidental, a banker who’d flagged suspicious withdrawals and gotten yelled at for interfering.

When it was my turn, I set my notes down.

“I could tell you about policies and pills and legal loopholes,” I began. “Instead, I want to tell you about a ring.”

I described the hospital floor, the taste of metal, the slap that made everything visible.

I described the quieter hits—the missing mail, the vanishing money, the way my mother’s body seemed to collapse in on itself under the weight of invisible chemicals.

“On paper, my mother wasn’t ‘vulnerable,’” I said. “She was under retirement age, working, living in her own home. She wasn’t in a facility. She didn’t have a dementia diagnosis. But in reality? She was completely dependent on the man who decided he owned her life.”

I paused, letting the silence settle.

“Abusers know how to work that gap,” I said. “They know exactly which definitions to slide under and which checkboxes to avoid. This bill doesn’t just close legal loopholes. It sends a message that we see financial and medical control for what it is: another form of violence.”

When I stepped away, one of the representatives—a woman with silver hair and a pin shaped like the state outline on her lapel—leaned toward her mic.

“Ms. Hester,” she said, “thank you for putting a human face on words we mostly see as numbers on a page.”

On the drive home, Mom folded the hearing agenda and tucked it next to Helen’s letter.

“These papers,” she said, “are the only kind I want to see in our file cabinet from now on.”

Every now and then, a letter still arrives from the Department of Corrections.

We’re notified about parole hearings, about transfers, about policy changes that might affect Gary’s sentence.

I have the right to submit statements.

For the first couple of years, I wrote long ones.

I spelled out everything—what he did, what it cost, why he shouldn’t be granted mercy he never offered others.

Recently, my letters have gotten shorter.

The last one I sent was only three sentences.

Gary Peterson turned my life and my mother’s life into a balance sheet. He calculated what he could take and how much we were worth if we disappeared. Keeping him where he is is the only way to make sure he never gets to balance another ledger with someone else’s body.

Sometimes, when I drop those envelopes into the mailbox at the end of our street, I think about the first time I tried to mail something important under Gary’s watch.

“How much is the stamp?” I’d asked once, holding a hospital bill.

“Too much,” he’d said, plucking it out of my hand. “I’ll take care of it.”

He never did.

Now, every squeak of the mailbox hinge feels like a small revenge.

I decide what goes out.

I decide what comes in.

On the third anniversary of the hospital incident, I woke up before my alarm.

For a moment, I didn’t know why my chest felt tight.

Then my body remembered before my brain did.

Tiles. Bleach. Metal.

I padded to the kitchen in my socks.

Mom was already there, humming under her breath, the coffee maker gurgling in the corner.

“Couldn’t sleep?” she asked.

“Couldn’t forget,” I said.

She slid a mug toward me.

“I was thinking,” she said slowly, “maybe we do something today.”

“Like what?”

She looked toward the IV pole propped in the corner of the dining room.

We’d gotten it from a medical surplus auction, cleaned and repurposed as a plant stand.

A trailing pothos wound its vines around the hooks.

“The hospital used to be where I thought everything bad happened,” she said. “But a lot of good people work there too. You up for a field trip?”

Two hours later, we walked through the automatic doors of the same ER where I’d been wheeled in bent double.

We carried a box of donuts and a stack of handwritten thank‑you notes addressed to “The Nurse With the Tattoo” and “Security Guard Who Called PD” and “Any Staff Who Press Call Buttons When It’s Hard.”

The charge nurse blinked when we explained why we were there.

“You’re… okay?” she asked.

“We’re better than okay,” Mom said. “We just wanted to close the loop.”

Nurse Rebecca wasn’t on shift, but someone texted her a photo of us standing under the wall‑mounted TV, our box of donuts between us.

She texted back a string of heart emojis and a message: Tell them I knew they’d make it.

As we left, I glanced at the IV poles lined up in the hallway.

Some had little plastic flags taped to them.

I reached up and straightened one that had bent.

It felt like the right kind of symbolism.

No more decoration.

Just a small, steady reminder that in places meant for healing, there will always be people willing to stand between you and whatever tries to knock you back onto the tiles.

I still wear the pendant sometimes.

Not because I need the reminder of Gary.

Because I like knowing that even metal can be melted down and reshaped.

A ring that once announced his victory now rests quietly against my skin, a small circle with no engraving.

It doesn’t scream for attention.

It doesn’t brag about a 300‑point game.

It just sits there, a tiny loop of gold that whispers a different story.

We were worth more than what he wrote on paper.

We always were.

And no one gets to slap that out of us again.

News

“You should’ve brought food from home, there’s bread on the table already,” my mom told my daughter in front of the whole family, then turned and beamed while my sister ordered extra tomahawk steak, wine, and fancy desserts — I just sat there like the ever “reasonable” daughter, until I ordered my kid a plate of pan-seared scallops, asked the waiter to move the entire bill onto my mom… and quietly kicked off the counterattack that would finally make them pay for their own favoritism for the first time.

The host stand was trimmed with fairy lights and a tiny enamel American flag pin that winked every time the…

“My ex-wife now only deserves some construction worker” – I bragged arrogantly to my friends before driving my BMW to the wedding just to laugh in her face. Little did I know that the moment I saw the groom standing on the altar, I froze, quietly turned my car around, and drove away in tears.

By the time the ice in my glass of sweet tea melted into a pale swirl, the little ceramic mug…

‘The House Is Ours Now. You Get Nothing,’ my daughter-in-law boasted at dinner. Her smile vanished when I calmly told her to explain the truth.

The cranberry sauce was still warm in my hands when my husband destroyed thirty-five years of marriage with seven words….

I rushed to the operating room to see my husband, but a nurse grabbed my arm: “Hide now — trust me, it’s a trap.” Ten minutes later, I saw him… and everything made sense.

It happened the night the sky decided to weep for me. The rain wasn’t just falling; it was hammering against…

My Mom Said I Wasn’t Welcome at Thanksgiving Because I’d Embarrass My Sister’s Boyfriend. I Hung Up. The Next Day They Came to My Door—And Her Boyfriend Spoke Words That Changed Everything.

My parents cut me from Thanksgiving with the casual indifference of someone trimming fat from a steak. There was no…

My Future MIL Told Me to Quit My Job and ‘Serve Her Son’ — Then the Manager Called Me Chairwoman

The crystal chandeliers of The Golden Spoon, the flagship establishment of the city’s most prestigious dining empire, cast a warm,…

End of content

No more pages to load