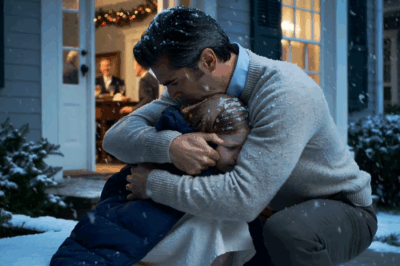

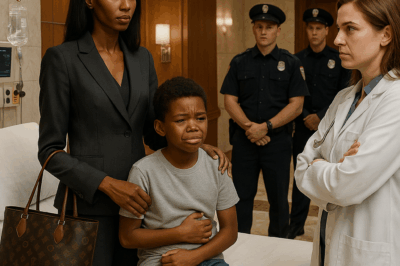

That first night in the hospital felt like a borrowed hallway, too bright and too quiet for honest sleep. A nurse wrapped a warm blanket around Emma’s shoulders and handed me a paper cup that steamed like a promise too small to keep. A detective took notes while I spoke, my own words sounding like they belonged to a stranger who hadn’t paid enough attention. Child services arrived with a binder and a voice that made room for Emma, asking questions that moved at the speed of trust. I signed forms I didn’t know existed until that minute, each signature a small oath that the past would not be allowed to repeat itself. When Emma finally drifted off, I sat beside the bed and tried to memorize the details of her breathing like they were instructions. Outside the window the city slept under frost, and the glass held our faces together in one reflection that refused to break.

When dawn came, the detective drove with me back to the house that still smelled like cinnamon and denial. We walked room to room while the sun inventoried the mess, and he photographed what I had trained myself not to see. He noted the locked back door, the thermostat set warm, the fresh glasses on the counter, the neat absence of a blanket by the porch. I opened drawers and found lists in Rebecca’s tidy hand that organized everything but mercy. We collected devices, pulled messages, and flagged the posts that turned cruelty into choreography. In the garage a box of decorations rattled when he lifted it, and beneath the tinsel lay a small pile of Emma’s confiscated things. I stood there holding the box like a confession, and the detective told me gently that confession was the beginning, not the end.

I called Emma’s mother from the driveway, and when she answered, we set aside the old arguments like wet coats on a line. She arrived at the hospital before the second cup of coffee cooled, and she did not waste a minute on blame. We agreed to be a two-person firewall and to argue later about every small thing except the important one. Co-parenting turned from a legal term into a daily verb that sounded like appointments, schedules, and shared notes. At night we traded updates by text and decided that no decision about Emma would be made without both of us in the room. We built the rulebook we should have had from the start and put Emma’s comfort at the top in letters big enough to read at a distance. It was not perfect, but perfection had never kept a child warm, and alignment did.

I wrote the first post like a police report wrapped in a prayer, attaching screenshots and dates and leaving out anything that belonged only to Emma. I kept the tone flat on purpose, because truth does better without adornment when you want it to stand up on its own. The comments came in waves, angry, shocked, and then practical, with people offering help, advice, and the names of attorneys who didn’t flinch. Friends reached out from old seasons of my life, and a quiet army began to assemble without trumpets. I learned to moderate, to let facts breathe, to block the handful of accounts that tried to turn harm into debate. By midnight the posts had traveled farther than our holiday cards ever had, and the receipts sat beside the smiles like uninvited guests. In the morning I pinned a resource list and reminded anyone reading that the first step is to call, not to scroll.

Rebecca’s employer called me in after HR finished their own reading, and the glass lobby felt like someone had Windexed the air too clean. I handed over a timeline and watched faces move from polite to professional to something like regret for what they had endorsed. They thanked me for the documentation, quoted policy about moral conduct, and ended her contract before the meeting ended. It was efficient, the kind of efficiency I had once admired, but my hands shook anyway because efficiency cannot carry a child. As I left, a colleague of hers stopped me to say they had noticed changes but never imagined the scale, which is another way of saying silence is crowded. Outside, I took a photograph of the building to remind myself that institutions can act faster than families when the rules are clear. I deleted the photo ten minutes later because Emma’s future did not need a trophy wall of other people’s decisions.

I reached out to the father of Rebecca’s former stepdaughter after a name in an old thread lined up with a story that made my chest feel tight. He called me back the same night, and our voices recognized each other before we exchanged details. He told me about the charm that curdled, the rules that always tilted, and the way his daughter learned to apologize for breathing. We compared notes like men repairing a bridge from opposite banks, careful with planks and careful with words. He sent me copies of messages he had kept for years because sometimes proof is the only thing that keeps memory from being argued away. By the end we agreed on one sentence, simple and heavy: this time we see it through wherever it goes. He hung up to check on his child, and I stood by the kitchen sink until the timer on a forgotten oven beeped at an empty pan.

The prosecutor assigned to our case spoke in calm paragraphs that made the floor feel steady under my shoes. She explained intent, pattern, and the way the law lets a history walk into the courtroom when it fits like a key. There would be a bail hearing, a protective order, and a sequence of filings that would look slow to anyone who hadn’t ever needed time to build a case. She asked for every document, every calendar entry, every note I had written to myself when I still thought I might be overreacting. Her team mapped the evidence into a lattice where each piece supported the others until the whole thing could hold weight. I left her office with less fear and more homework, which is not how I usually leave government buildings. That night I labeled folders with dates and slept for the first time without dreaming of locked doors.

Therapy began with crayons and silence, which is a better pairing than most adults remember. Emma drew houses with three windows and a door left open, and the therapist asked questions that fit inside the white space. Some days the paper filled with clouds, and some days a single line ran from edge to edge like a power line carrying something invisible. I learned to wait for her to speak and to measure progress by comfort rather than volume. The therapist explained how trauma nests in the body and how art gives it somewhere to land without breaking the furniture. On good afternoons Emma laughed at a joke and then checked the room, and we practiced staying present until laughter no longer needed permission. When we left, she would press the elevator button like she was choosing today on purpose, and I took that as a victory worth counting.

The school counselor met us at the side entrance with a smile that didn’t ask for anything back. Teachers adjusted deadlines, shifted seating, and watched for the small signs that tell the truth before the words do. Emma’s art teacher found space for her during lunch and kept the sink running warm so the brushes didn’t bite her hands. Kids can be cruel without meaning to, so we gave classmates language for kindness and drew boundaries that even fourth graders could read. When a bully tried a whisper campaign, Emma stood beside another child who had been singled out, and they folded the whisper into a quiet friendship. Her report card came back with more notes about effort than grades, and no one complained because effort is what you grade when healing is the assignment. At pickup she told me the school felt bigger now, and I realized safety expands square footage without filing a permit.

The fundraiser took place in the gym that smelled like varnish and hope, with folding chairs that tried their best to behave. The principal spoke in careful terms about prevention and reporting, and no one needed a replay of harm to understand the stakes. Parents baked, kids painted banners, and a local band tuned for longer than they played, which is how you know they cared. On a long table we laid out resources instead of trophies, and volunteers wrote hotline numbers in pen that wouldn’t smudge. Emma watched from the bleachers and waved when a classmate brought her lemonade, and the wave looked like something new settling into place. We raised more than the goal, but the real measure was the stack of forms people took home to their own refrigerators. Driving back, the car felt full of names, and I promised myself to remember them when the quiet days returned.

The day of the name change, the courthouse hall echoed with heels, clipboards, and decisions being made in ordinary voices. The judge smiled at Emma and asked her to say the new name out loud, and she did, with a steadiness that made my throat ache. We signed papers that felt lighter than their importance, and an embossed seal pressed the present into the future. Outside, we took a picture by the stone steps, and even the wind behaved long enough for the hair in her face to settle. She tucked the certificate into a folder like a ticket, and we celebrated with pie because cakes were booked for other people’s milestones. In the car she practiced the signature until it looked like handwriting rather than hope. When we got home, I labeled a new mailbox slot, and she slid the folder in like a letter to herself that would always be forwarded.

The trial unfolded over several long days that made clocks feel like unreliable narrators. The defense tried to recast neglect as misunderstanding and cruelty as discipline, but the record did not bend. Witnesses spoke in voices that shook and then steadied, including the former stepdaughter who walked through her own map without asking for pity. The prosecutor threaded the pattern together until it read like a blueprint no one wanted to recognize. The judge kept the room respectful and closed every door that led to spectacle. When the verdict came, it felt less like a bang and more like a door finally opening in a house we had been trapped inside. I held Emma’s hand and counted our breaths to seven, because ritual is what you do when words aren’t enough.

At sentencing the statements were brief and exact, built from facts and the kind of restraint that keeps a heart from tearing. Rebecca stared ahead, Patricia looked down, and neither found the sentence that could have changed the temperature in the room. The judge spoke about duty, intent, and the trust the community places in adults, assigning years that matched the weight of the harm. No one cheered, because accountability is not a party; it is the slow work of balance returning. Afterward Emma asked if we were done, and I told her we were finished with court but not with care. We walked into daylight that didn’t require us to glance at shadows first, and that was enough for one afternoon. On the ride home the radio played a song she liked, and I let it run all the way through without checking the news.

The civil case moved like math, with numbers that seemed too large when attached to a childhood and too small when attached to pain. Lawyers structured a trust to hold therapy, schooling, and the ordinary futures a child deserves without needing to ask twice. Settlements landed in accounts with names that protected them from the storms grown-ups create. Insurance forms multiplied, valuations were argued, and somewhere in there we remembered to eat dinner at a table that didn’t host documents. Emma’s mother and I kept the conversations focused, because our job was not to win but to build the runway. When it ended, the relief was quiet and practical, like a light turning on in a hallway you walk every day. We filed the last binder and put it on a shelf we only use for things we hope never to revisit.

In the months that followed, the women’s assets thinned, their friends drifted, and their online profiles read like empty rooms. I heard they tried to move twice and failed once, and then I stopped checking because vigilance and obsession are neighbors with a thin fence. Occasionally a letter arrived from an agency we’d already spoken to, and I filed it with the rest, unremarkable as a utility bill. There was no apology, which saved us the trouble of deciding what to do with one. The best closure we got was the absence of their names from our daily calendar. I learned that peace isn’t the opposite of noise; it is the decision not to invite certain sounds back into the house. Emma learned it faster than I did, which is one more way children teach their parents how to live.

We built new routines that stayed small on purpose so they could be kept. On Sundays we tried recipes with too many steps and laughed at the parts that refused to cooperate. We adopted a rescue cat who walks the perimeter before bed like a furry security system that purrs. The thermostat is set to comfortable, the porch holds blankets in a bin, and the front door answers the bell on the first ring. Emma hangs her art on a wire in the hallway, and I leave the clothespins crooked because perfection has already done enough damage. Sometimes we eat pancakes for dinner, and no one asks whether it is an appropriate time for syrup. At night I check the locks out of habit and then sleep without needing to get up and check again.

In a parents’ group I said the word guilt out loud and did not burst into flames, which felt like progress. A counselor told us that love is not measured by what you missed but by what you do when you finally see. I wrote Emma a letter I didn’t intend to give her yet, explaining the difference between explanation and excuse. I keep it in a drawer with the good scissors and take it out on days when my chest feels crowded. Some weekends we volunteer at a hotline training, and I stand in the back taking notes like a student late to class. People share stories that tilt the room, and each one becomes another reason to keep the line open. When I drive home, the dashboard glow looks less like a warning and more like a compass I can finally read.

Spring brought puddles, longer light, and the sound of sneakers squeaking in school hallways after clubs. Emma started helping the art teacher sharpen pencils and set out paper for younger kids who crowded the table with bright impatience. She taught one boy how to draw a door that looks open even when it’s closed, and he laughed like he had learned a magic trick. I framed her painting of a small porch with a lantern, and we hung it by the front door with nails that finally found the stud. Visitors pause there, and she tells them colored pencils can be stronger than paint when you want to show how light moves. She’s saving for a kid-safe easel and talks about lesson plans like they are maps to places she already knows. I listen and take notes, because someday I want to remember the exact words she used for the first class she’ll teach.

When people message me asking what they should do, I tell them the same three verbs every time: notice, name, act. Notice means keep your eyes open even when the picture looks fine from across the room. Name means say the thing out loud so the air can start to clear and help can find the right address. Act means call, document, knock, and keep knocking until someone answers who can unlock the door you cannot. Keep receipts, trust your gut, and choose the child over your pride no matter how expensive that choice feels. If you are wrong, you will apologize and learn; if you are right, you will have saved a life that still needs breakfast tomorrow. I learned all this the hard way, which is not a brag but a map I wish someone had handed me sooner.

On quiet evenings we sit on the porch with the blankets folded and the lantern lit, and the cold is just weather now. Emma sketches the trees across the street while the cat pretends to stalk a moth that will not be caught. I think about the man who came home one winter night and found a child outside, and I let him fade into a chapter title instead of a curse. The neighborhood kids ride past on scooters and yell hello, and the echo lands inside the house without asking permission. Tomorrow there will be school, and therapy, and dishes, and a list of chores that says normal in seven lines. We are not a perfect family, but we are a practiced one, and practice is how songs become music. When we go back inside, the door closes softly because we have taught it how to treat us.

Summer came with the slow courage of warm mornings and a calendar that was no longer crowded by court dates. Emma joined an afternoon art camp at the community center, carrying a sketchbook that looked heavier than it was. She learned how to mix colors like a recipe and how to clean brushes without rushing, which felt like a lesson about more than paint. I waited in the lobby with other parents and answered friendly questions without telling the story behind our punctuality. We stopped by the park on the way home and drew trees while the cat tracked shadows across the living room window at home. The therapist called these weeks integration, a word that sounded like a bridge held together by small, regular nails. At night, when the air finally cooled, we left the porch light on as if reminding ourselves that the house knew how to welcome.

In July we drove to the coast with a cooler and a plan to be unambitious. Emma sketched gulls that looked like check marks against the sky and labeled the horizon with the date like a careful archivist. We walked a pier that used to make me nervous because of the gaps between the boards, and this time we laughed at the same gap twice. At a used bookstore she found a guide to teaching art to kids and read it out loud in the car until she fell asleep mid sentence. Back home we started a small porch project, collecting blankets and leaving them in a bin with a note that said, Take what you need. The first blanket disappeared on a rainy night, and instead of worrying, we called it proof that the sign spoke the right language. Emma added a drawing of a lantern to the note, and the paper curled at the edges like a smile that had done its job.

A reporter reached out in August, kind in tone and careful with questions that could have endangered privacy. We met at a coffee shop and I kept the details at arm’s length, offering lessons instead of scenes and principles instead of plot. She asked what I wished I had known, and I said that people who justify small cruelties are auditioning for larger ones. She asked how Emma was doing, and I said she was learning to choose her afternoons, which felt like a real metric. When the article came out, it centered on resources and left out our faces, which is how I knew we had chosen well. Some readers wrote to say they were finally naming what they had suspected in their own homes, and I saved those notes in a folder. I told Emma that people she would never meet were safer now, and she nodded in that slow way that means the idea found a chair.

In therapy Emma tried a new technique that involved breathing and tapping, and she came home amused that science could look so simple. She said the memories were still memories, but they felt like files in a cabinet instead of birds trapped in a room. We practiced grounding with cold water on our wrists and lists of five things we could see, which made us experts at noticing lamps. On hard days she drew the old house as a box with no windows, then added a door and colored it open until the page looked lighter. I kept my own appointments and admitted how quickly I used to forgive what I did not understand. The counselor told me that vigilance can grow into wisdom if you give it boundaries and let it sit down. We wrote that sentence on a card and taped it inside the pantry where practical truths belong.

At the school open house the hallways smelled like glue sticks and pencil shavings, which is to say they smelled like new chances. Emma’s art hung beside the library door, a line drawing of our porch lantern casting calm across an empty step. Her teacher introduced me to parents who said their kids had started drawing doors slightly ajar, and I thanked them without explaining why that mattered. We stood by the display and watched small hands point to the lantern as if a light on paper could warm your palms. A boy asked Emma how to make shadows without making them scary, and she answered like a coach who had done the drill a hundred times. The principal shook my hand and said the school had a new protocol for reporting concerns, and I felt the building stand a little straighter. On the way out, Emma slipped her fingers into mine, and the gesture felt like a quiet closing argument that needed no judge.

One Saturday I drove back to the old neighborhood to thank the couple who had checked on us when the sirens came. They met me on their porch with mugs and a blanket across their laps, and the blanket made me smile without warning. We talked about weather, and gardens, and the way a street keeps its own memory even when houses change owners. When they asked about Emma, I said she was painting light now, and they nodded as if light were a person they had always liked. I left them a note with hotline numbers and a promise to return if they ever needed another pair of ears. On the drive home I noticed how the trees arched over the road like a hallway that had finally learned where it led. I rolled the windows down and let the sound of leaves replace the last sounds I had been carrying from that block.

Back in our garage I opened the box the detective had set down months ago, the one that rattled under the tinsel. Inside were small confiscations from another era, treasures taken from Emma as if joy were a luxury tax. We laid each item on the workbench and talked about what to keep and what to give away, letting her be the curator. She kept the sketchbook even though most of the pages were blank, because blank pages are still proof that space existed. She donated a scarf to the porch bin and smiled at the idea of it warming someone who had not expected kindness that day. We recycled the cracked plastic barrettes, a ceremony so minor it felt major. When we closed the lid, the garage smelled like clean dust, and the box looked lighter even before we moved it.

Autumn arrived dressed in small golds and outran our summers by an hour of darkness. I built a bench for the porch out of lumber that had been waiting for a reason, measuring twice like a man who had learned the cost of sloppy work. Emma sanded the edges and marked the underside with her new name, a signature almost steady now. We sealed the wood and stenciled the words Open Door Bench on the back like a promise we could sit on. Neighbors tried it out and mentioned the view as if we had moved the horizon closer. At night the bench held the blanket bin like a dock holds a boat, and I liked the way both ideas suggested leaving and returning. When the first cool wind lifted the porch flag, the bench did not creak, which felt like a small engineering compliment.

In late October a letter arrived from the facility where Rebecca is serving her sentence, stamped and official in a way that made my stomach tighten. I brought it to my counselor before I brought it home, and we discussed the difference between curiosity and reopening a wound. We agreed the letter belonged unopened in a file for legal matters, far from the drawer where we keep birthday candles and tape. I told Emma only that sometimes mail is not for us, and she accepted the boundary without asking for the story. That night I shredded the envelope after photographing it for the file, deleting the photo after the document had been saved. The act felt both theatrical and boring, which is exactly how I want certain chapters to end. I slept well, which felt like a correct answer to a test I had once failed.

There was one more restitution hearing, a tidy morning of numbers and nods in a courtroom that had learned our names. I spoke briefly about ongoing therapy costs and the way consistency buys progress you can measure in school weeks. The judge approved the structure without fuss, and the order read like a fence built around basics. Afterward I thanked the clerk who had shown me where to stand on the first day, because kindness is the only detail that keeps bureaucracy human. We walked past the news cameras without stopping, and it felt less like turning away and more like facing the right direction. At lunch Emma asked if the case was a book now, and I said it was a filed chapter we no longer needed to reread. She asked if filed chapters get dusty, and I said yes, and that dust is a sign you are busy living.

The first snow came early and soft, laying a quiet over the street that made cars look polite. We stocked the porch bin with thicker blankets and added a small thermos station with cups that nested like good ideas. A neighbor left a note that said Thank you for making cold nights less lonely, and it was signed only with a heart. Emma clipped the note to the bin with a clothespin and said that gratitude should be displayed like a flag. One evening we watched a young couple take a blanket and walk down the sidewalk holding its corners together at the front. We stood inside the door and said nothing, because some scenes ask to be witnessed rather than narrated. When the latch settled, the house felt warmer by a degree I could not find on the thermostat.

On the anniversary of that winter night we set a new table and called it tradition without asking permission. We cooked soup that did not burn and baked bread that rose like the kind of certainty I used to envy in other families. At dusk Emma turned on the lantern and placed a fresh blanket on the bench, smoothing the fold with a practiced hand. Neighbors stopped by with cookies and short stories, and no one asked for the origin of the evening because they already knew. We opened the door every time the bell rang, and the bell rang enough to become music. When the hour matched the memory, we stood on the porch and looked at the empty step, which was no longer an accusation. We went back inside together, and the door closed softly, the way a house closes around the people who taught it how.

In January we boxed the ornaments and left the lantern up as a year-round promise. I fixed the squeak in the front door because peace should not creak. Emma found the old camcorder I used when she was a toddler and smiled at its clumsy weight. We watched two minutes of her first steps and turned it off before nostalgia lied about what we missed. She recorded a new clip of the porch at dusk and narrated like a weather reporter training her voice. Later I played it back and heard steadiness between words, the kind of calm you cannot fake. I saved the file under the name Open_Door_One and understood why people number beginnings.

By February we had a conversation about what dating might someday look like, and we did it at the kitchen table with the cat asleep between us. I told her grown-ups sometimes look for company, the way you look for a good book you can read slowly. She said she wanted a veto until she was ready to meet anyone, and I agreed before she finished the sentence. We set rules that sounded like respect translated into calendar terms. No surprise introductions, no shifting of routines, no rerouting of bedtime. She laughed and said she’d like to interview any candidate like a principal hiring a teacher. I laughed too and meant it, because the interview would be real if the day ever came.

In March the appellate hearing came up on the docket like a stubborn echo that refused to learn the new song. I took the morning off work, sat in the back row, and let the attorneys speak languages built from footnotes. The court kept the original judgment intact, and the protective order was renewed with the same firm lines it had before. I signed the new paperwork with a hand that did not shake and thanked the clerk by name. On the steps outside I stood still until my breathing matched the city’s ordinary pace. I texted Emma one sentence that said, All set, and she replied with a thumbs-up and a paint palette. We kept the day ordinary on purpose, because victories are stronger when they fit inside Tuesdays.

Spring turned the school into a gallery, and the art show spilled down the hallway like careful joy. Emma’s series of lantern drawings hung together in a row, each one showing a different kind of evening. The teacher said a small arts nonprofit loved the work and wanted to sponsor a summer workshop for her and two classmates. We talked to the organizer after the bell and said yes with the kind of caution that reads the fine print twice. The contract protected her privacy and asked only for first names on a flyer pinned to the library corkboard. She came home buzzing like a charging phone and laid her pencils out in a neat line. That night she drew a lantern with the bulb just switched on, a moment caught between decision and light.

I went back to the parents’ group and found myself answering more questions than I asked. A father new to the circle told his story in a whisper that made the room tilt, and we waited until he finished breathing. I gave him the three verbs we live by and added a fourth he could hold in his pocket, which was repeat. He called the hotline on a bench outside while I stood near enough to be company and far enough to let him own the call. The operator moved quickly, and I watched relief arrive in increments across his face. When he hung up, he looked taller by a fraction you could still measure. We walked back inside and wrote the number on the whiteboard in marker that doesn’t fade.

By early summer our porch bench had cousins across the neighborhood, small stations that looked like ours with their own handwriting. Someone made a map on the community page and titled it Open Door Bench Network, which sounded bigger than it was and exactly the right size. Thicker blankets appeared near the apartment buildings where wind funnels into corners. A retired carpenter built a bench with armrests that folded into tiny shelves for a book and a cup. The school librarian stocked a weatherproof box with paperbacks no one seemed to miss. On my evening walks I counted benches the way runners count streetlights. Every count felt like proof that an idea can travel on foot.

We planted hydrangeas along the fence because Emma liked the way the blossoms hold blues like secrets. The soil tested a little acidic, and the nursery clerk showed us how to balance it without scolding us for not knowing. We watered in the short hour after dinner when the light looks patient. The cat supervised from the stoop as if color choices required oversight. In a month the shrubs took and threw new leaves, small emblems of perseverance you can actually photograph. Emma sketched the first bloom and shaded the petals with the pencil she calls storm gray. I pressed the drawing into a frame and hung it by the thermostat like a seasonal forecast.

The rescue group called with a question that came with a photo, and the photo looked like a dog who might understand porches. We fostered him for two weeks as a trial and renamed him Beacon because some names arrive already trained. He learned the perimeter in three days and slept by the door like a security detail with a soft belly. Emma taught him to wait before walks, a lesson she said people should learn with leashes too. In the mornings Beacon followed her from room to room as if moving light needed a witness. When the rescue asked if we wanted to make it official, the signature felt like the easiest paperwork of the year. The cat, offended at first, finally agreed to share square footage with democracy.

The nonprofit’s summer workshop put Emma at a long table with kids who drew with the kind of concentration that makes rooms hushed. She planned a mini-lesson on drawing open doors that look inviting, not threatening, and practiced the steps on our refrigerator. The instructor praised her for how she explained horizon lines without sounding like a textbook. At the final session each kid drew a place that felt safe, and Emma’s drawing included a bench with a folded blanket and the ghost of a cat’s tail. Parents walked the gallery of taped-up pages like they were touring countries with familiar flags. A donor pressed a small scholarship toward her next year’s supplies, and I watched how careful she was saying thank you. On the ride home she said teaching felt like breathing without the part where you forget how.

I wrote another letter to future Emma and titled it After the Workshop, because labels help me keep promises. I told her the bravest thing she does is stay open without letting anyone rearrange her furniture. I listed the names of people who showed up when it mattered, because gratitude is a map too. I admitted that I still check the porch camera more often than necessary and that I’m working on it. I told her that love is a schedule you keep, not a feeling you perform. I sealed the letter and put it in the drawer with the good scissors again, increased now by two quiet truths. On its envelope I wrote, For a day when patience feels thin.

One afternoon in September the former stepdaughter called to say she had started a class in early childhood education. She said reading about development made the past look different, not smaller, just better labeled. We compared calendars and sent each other silly photos of notebooks stacked like skyscrapers. She asked about Emma’s art and said she had shown the lantern drawings to a friend who cried in a good way. Before hanging up she said, I’m okay now, and the sentence landed like a clear bell. I stood in the kitchen and listened to the echo until it settled into the tile. Then I texted Emma a small update that would mean a large thing.

On a field trip we took the train to a museum and found ourselves in front of a painting where a quiet room held brighter weather at the window. Emma pointed out how the light crossed the floor and asked me how long it took the painter to decide. We stood there long enough that the guard smiled like he approved of slow looking. In another gallery we found a series of sketches that showed how a lantern becomes a lamp without losing its job. She took notes as if she would have to teach the painting later, which she might. At the gift shop we bought a single postcard instead of a poster and left room in the bag for air. On the way home we sat by the door the way we always do, and the train learned our names again.

October brought rain that sounded like sincerity and leaves that argued kindly with the gutter. We hosted a porch clinic one Saturday for neighbors who wanted to copy our bench and didn’t know where to start. I drew plans on cardboard and let the mistakes show, which made everyone more willing to begin. Someone brought donuts, someone else brought a drill, and every screw found a home eventually. Emma taught the kids how to sand with even strokes, and Beacon made friends by supervising crumbs. By afternoon three new benches stood on three new porches, each stenciled with its own version of invitation. At dusk I took a walk and said hello to invitations I hadn’t written.

As winter edged back, I brought the blankets inside for a wash and counted them the way you count blessings when you’re practical. We replaced two worn ones and added an electric kettle to the thermos station for nights that asked for steam. Emma practiced a short speech for the school assembly about art and kindness, and I timed her without making a face. She finished in under three minutes, which is the only kind of speech people remember. The counselor asked if she would mentor a younger student for six weeks, and she said yes like she had been waiting to be asked. I cleared a corner of the living room for a second easel and pretended it didn’t make me emotional. The house said nothing and held the change without creaking.

On the second anniversary we kept the tradition, but we swapped the soup recipe for one that uses rosemary like a memory that learned manners. The neighbors still came by with small stories, and the lantern did its job without being asked twice. I watched Emma place a new blanket on the bench and smooth the fold like a ritual we had perfected. We stood on the porch for the minute that used to be a cliff and discovered it was a step. Inside, the cat and the dog circled the rug like a committee approving the agenda. We toasted with hot chocolate and let the quiet do the heavy lifting. When the bell rang, we opened the door before it finished its sentence.

January opened into a calmer school term, and Emma practiced her assembly speech until the kitchen timer could recite it. She spoke about art as a way to show feelings without asking them to perform, and the auditorium listened like a good friend. Afterward, the counselor introduced a fourth grader who liked to draw but hated lunch, and asked if Emma would mentor her for six weeks. Emma said yes, set a schedule on the family calendar, and named the meetings Brush Club. They ate crackers at the back table, sketched doors with gentle shadows, and traded jokes that sounded like small handrails. I watched from the hallway and learned how leadership begins with noticing who hangs back. When the cycle ended, the younger girl left a note that said thank you for the soft pencils, and Emma pinned it inside her locker like a quiet medal.

In February I kept my promise about honesty and went on a daytime coffee with a friend of a friend named Carla. We met in a bright café that smelled like oranges, talked about books we actually finished, and kept the subject of history general. I told Emma beforehand, asked if she wanted a veto without reasons, and she nodded like a manager approving a trial run. Carla knew the rules and respected the schedule, which is a way of saying the coffee stayed coffee. When I came home, Emma asked two questions—Was the place crowded, and did you laugh—and I answered yes and yes. She said good, turned back to her homework, and reminded me that trust prefers reports over summaries. We let the subject rest, because rest is part of any plan you intend to keep.

Emma’s mother and I kept our co-parenting calendar clean and shared, and we held a family meeting on the first Sunday of each month. We used index cards for schedule conflicts and a separate stack labeled Feelings so the logistics didn’t swallow the truth. Sometimes the meetings lasted ten minutes, sometimes an hour, and the length never correlated with importance. We agreed that holidays would be planned like bridges, not battlegrounds, with everyone able to cross without paying tolls in old arguments. When disagreements surfaced, we borrowed the therapist’s rule of naming the goal before naming the problem. It made the room gentler, and gentleness kept the door open when the cat tried to close it with her shoulder. Emma watched us practice and learned that adults can disagree without making the furniture flinch.

One afternoon a fire alarm test went off early, and the sudden siren lifted Emma’s shoulders to her ears. She froze for a breath, looked for me, and then remembered the steps taped inside her binder. Five things she could see, four she could touch, three she could hear, two she could smell, and one safe thought she could keep. By the time I reached the office, she was steady, a little pale, and proud of not needing the nurse’s cot. We sat on the front steps and counted cars until the noise in her body dropped to street level. The principal joined us and said the school would add warning banners when drills were scheduled, which cost nothing and meant everything. We walked home under a sky that had learned to turn the volume down.

In April a notification arrived about a parole review, the kind of envelope I have learned not to open alone. The prosecutor prepared a brief and asked if I wanted to add a statement, and I wrote the words I needed on a single page. I spoke about progress, boundaries, and the quiet work of a child rebuilding a life that was interrupted. I did not dramatize; I described, because description is the least slippery way to respect the truth. The board listened, the record stood taller than any speech, and the request was denied without hesitation. I called Emma’s mother from the parking lot and said only we’re clear for now, which was the right size for relief. At home we cooked pasta and watched a movie with a happy ending that did not lie about effort.

By May the Open Door Bench Network had a page of its own, a small map dotted with addresses that felt like candles on a shared cake. We wrote a one-page guide that covered basic safety, upkeep, signage, and the difference between welcome and performance. A city council member asked for a meeting, and we brought data instead of drama—numbers of blankets, nights of frost, and notes from grateful strangers. The council voted to add mini-grant vouchers for winter supplies, and the motion passed without anyone needing to make a speech about weather. Local shops offered discounts, the library hosted a sewing night, and a scout troop learned to stencil letters that don’t peel. I registered a simple nonprofit with a name that sounded like a light, and a treasurer who likes spreadsheets volunteered before I finished the sentence. We kept the budget transparent and small, because small things kept often beat large promises broken.

Emma submitted a portfolio to the community arts festival and taped the receipt to the fridge like a boarding pass. She chose three lantern drawings and one bold experiment where the door was open so wide it almost left the page. The jurors selected her work for the youth wall, and the program spelled her first name only, just the way we asked. At the opening she held my elbow, took a breath, and then let go to stand with her friends near the cookies. A teacher from another school asked if she would speak to a class about drawing light, and she said yes after checking her calendar. On the drive home she said the room felt different when her picture was on the wall, and I said that’s how rooms say thank you. We celebrated with sandwiches and the good ginger ale, which is our way of letting achievements be delicious instead of loud.

In July we drove west to a national park where the trails climb like careful sentences. Beacon trotted within the rules, the cat stayed home with a neighbor who sends photos, and the car learned a new hum. Emma sketched switchbacks and wrote small notes about shadow, elevation, and the smell of pine that refuses to be captured. A ranger explained how controlled burns prevent larger fires, and we nodded at the metaphor without overworking it. At a lookout we ate oranges and talked about fear as a path you can walk with handrails provided by practice. On the last morning the valley filled with a fog that looked like a secret learning to become a story. We drove home a little quieter, which is often how happiness sounds when it has been earned.

In late summer the former stepdaughter visited for an afternoon that stretched into dinner because the conversation kept finding new rooms. She and Emma compared notes about coping skills, favorite teachers, and the way time moves faster in safe houses. We set clear boundaries about the past, answered what we could, and set aside what belonged to closed chapters. She brought a small plant and said growth felt better when you could water something on purpose. They drew side by side for an hour, two lanterns facing each other like neighboring windows. When she left, she said see you soon, and the words felt like a promise made to the future rather than a rescue from the past. I washed the cups and thought about how healing multiplies when it has company.

Back home I wrote a practical guide called Notice, Name, Act, Repeat and posted it to the community page without photos. It included sample scripts for hard calls, a checklist for documenting, and a list of agencies that answer at midnight. The PTA printed copies for a back-to-school folder, and the principal asked me to speak for five minutes about logistics only. We kept the talk short enough that no one’s hands fell asleep and clear enough that no one mistook energy for readiness. A parent emailed to say the guide turned dread into steps, which is the best we can ask from paper. I saved the email in the same folder as Emma’s notes, because both are proof that words can move furniture. When I passed the benches that week, they seemed to nod at the idea of instructions that fit on one page.

Emma started an after-school club called Lantern Table, open to anyone who wanted to draw or just sit near safe light. They met on Tuesdays in a corner of the library where the carpet forgives spilled pencil shavings. The club applied for a small grant to buy sketchbooks for kids who forgot theirs, and the award letter arrived with enough for snacks too. She designed a simple logo, and I showed her how to set up a ledger that counts cookies as supplies when cookies are supplies. The librarian said the noise the club makes is the kind that libraries are built to hold, which felt like policy disguised as kindness. A shy boy started bringing his little sister, and Emma set out a chair for her without fuss so it would look like it had always been there. By October the club list had more names than seats, and the waitlist read like a neighborhood learning to trust itself.

In December a hard storm knocked out power for a long night, and our block turned into a quiet campsite. We hauled out battery lanterns, set up a kettle on the camping stove, and posted a note that said warm drinks inside if needed. Neighbors came in pairs, shook off snow, and sat with cheeks flushed like they had been running with good news. We played cards by lantern, taught Beacon to nap while people shuffled, and let the cat supervise from the highest chair. Someone read a chapter of a book aloud, and the living room learned a new way to be a shelter. When the lights returned, no one clapped, because it felt better to finish the hand. After the last coat left the hook, the house exhaled and kept a little of the warmth for later.

My counselor suggested we taper sessions, not because the story was finished, but because it had learned to walk on sidewalks. I brought the letters to future Emma and read them aloud into an empty room, surprised by how ordinary my voice sounded. I gave her the first one, the one about beginnings, and she read it on the couch with Beacon’s head on her knee. She looked up halfway through and said you were learning too, and I said I still am, which is the only honest answer. We filed the rest for later days, the way you store winter blankets after spring proves it will stick. On the way out of the clinic, I held the door for a stranger, and the hinge didn’t squeak, which felt like a metaphor earning its keep. That night I slept six straight hours and woke up to a morning that did not ask me to justify itself.

The next spring brought middle school and a small gallery show where student work hung beside pieces by local artists. Emma’s statement read, I draw doors because I like choosing which way light goes, and the simplicity did the heavy lifting. She stood at the mic for two minutes, thanked the mentors by name, and did not apologize for taking up space. I watched from the back and kept my hands in my pockets so I wouldn’t try to hold the whole room. A woman who teaches at the art college asked for a portfolio email and handed over a card with soft corners. We walked out into a drizzle that didn’t bother to be dramatic, which suited the evening fine. At home she taped the card inside her sketchbook and wrote not yet beside it like a promise with patience.

On a calm Sunday a family we didn’t know paused by the bench, read the note, and knocked with the kind of knock that leaves room to refuse. We opened the door and offered tea, and they asked only for directions to a resource we had on the list by the phone. Their little boy petted Beacon and traced the letters on the bench with a finger that looked more curious than afraid. We made the call together, wrote down the appointment time, and sent them off with a blanket that matched the weather. After the latch clicked, Emma said the map works, and I thought about how maps are just stories that learned to be useful. We sat for a while on the bench we built, watching the porch lantern do its quiet job without needing applause. When we finally went inside, the door closed softly, as if the house had practiced too.

Weeks passed in a rhythm that did not need a conductor. Emma sketched between homework problems and left graphite fingerprints like signatures on the margins. I learned which stores restock paper on Fridays and bought two packs only when the shelf looked crowded. Beacon mastered the trick of lying across the doorway as if guarding the idea of entry. The cat took to the back of the couch like a lighthouse that blinks without drama. On Sundays we wiped the porch bench and checked the screws for drift. Ordinary maintained its shape, which is a skill I no longer take for granted.

One evening the art teacher emailed to ask if Emma would assist in a Saturday workshop for younger kids. She read the message twice, checked her calendar, and nodded as if answering a question in a new language. We set out pencils, kneaded erasers, and a stack of practice sheets that could carry mistakes. At the workshop she showed a child how to draw a hinge so a door could appear open without begging. The room settled into a working quiet that felt like respect wearing sneakers. Afterward the teacher handed Emma a twenty-dollar stipend and a handwritten thank you. She tucked both into her sketchbook and said it felt like being paid to breathe.

I met Carla for a walk in the park and we stayed on the wide paths where conversation can pass people safely. We talked about porch projects and books that forgive readers for skipping pages. I told her I was not looking for a headline, only a paragraph that could live beside the others. She said she liked paragraphs that knew where they were going without rushing. We agreed that Emma would not meet her until Emma said so, and that no one would audition in the living room. When I got home, Emma asked the same two questions and I gave the same two answers. Routine held the door open for patience, and patience did not complain about the draft.

The nonprofit filed its first annual report and the treasurer brought cupcakes to celebrate numbers that added up. We published a winter guide on the website with clear photos of bench parts and step counts that matched the boards. A hardware store donated screws after a clerk recognized the logo from a neighbor’s porch. Volunteers formed a Saturday loop to check bins and replace notes blurred by rain. A retired nurse drafted a simple protocol for wellness checks that respected privacy and reality. We added a sentence about calling first and knocking second, and it felt like a hinge finding its pin. The map grew by three more dots and no one called it a movement because movements need marching.

In autumn Emma auditioned for a magnet art program and set her portfolio on a table that had seen thousands of hopes. She presented the lantern series and a new set of drawings about benches in different seasons. The panel asked calm questions about line weight and composition, and she answered without swallowing her voice. I sat in the hallway reading the same paragraph of a novel until the ink felt familiar. When she came out, she smiled the small smile that means a bridge held. Weeks later an envelope arrived with a line that began with congratulations and landed gentle. We taped the letter beside the thermostat where courage is measured daily.

The former stepdaughter sent a photo of her classroom with tiny chairs and a bulletin board about feelings. She asked if she could visit Emma’s Lantern Table to talk about how teachers make rooms safe on purpose. The kids listened while she described check-in charts and the power of predictable snacks. Emma showed a drawing of a door with a window small enough to see out and big enough to wave. Afterward they compared lesson plans like friends comparing recipes that travel well. I watched them pack up and felt the simple pride of witnessing chapters overlap without tearing. On the drive home they planned a joint workshop and argued happily about whether tape or tacks were kinder to walls.

The parole letters stopped coming, which is the kind of news that arrives as silence. The prosecutor sent a routine update that fit on one page and asked for nothing back. I filed it with the others and noticed the folder was getting easier to lift. Emma asked if anything had changed and I told her the calendar was quiet. She nodded and drew a door with a thick frame, then added a latch that looked like it worked. We went for ice cream and did not mention the past to make room for chocolate. On the walk home Beacon found a fallen glove and carried it like a trophy of gentleness.

Winter arrived with clean cold and early dark, and the bench learned again how to host kindness. The Open Door page posted a call for knitters, and within a week a bin of hats arrived like a chorus. Emma organized sizes with clothespins labeled small, medium, and brave. A neighbor left heat packs and a note that said for hands that need a minute. On the coldest night we brewed tea until the windows fogged and the living room smelled like citrus. People came and went with careful footsteps that made the floorboards sound like gratitude. Later, as we washed cups, Emma said warmth is just planning plus water.

At the new school Emma learned printmaking and came home with ink on her fingers and a grin that aimed in two directions. She carved a lantern block and pulled a dozen clean prints, each one a little different on purpose. We researched non-toxic inks and set up a small table near the back door where ventilation behaves. She sold a few prints at the winter fair and donated half to the bench fund without being asked. The receipt book looked almost official even with my crooked handwriting. Her teacher wrote a note about leadership that fit neatly into a frame. We put it by the light switch because we like reminders on the way out.

Carla and I kept the pace careful and clear, and one evening we invited her to join a porch shift for the bench. Emma agreed on the condition that the evening stay about the bench and not about introductions. The three of us set out cups and folded blankets while Beacon patrolled the steps. Carla told a story about her grandmother’s porch in a town that measured storms by song. Emma asked two practical questions about kettles and lids and decided the answers were adequate. We watched the street breathe in quiet rhythms and let the conversation stay small. When the shift ended, Emma said good night in a tone that means maybe.

The parents’ group asked me to update the guide, and I added a section on recovery that credits boredom as medicine. I wrote that ordinary routines are not a step down from crisis; they are the step up to living. I included a page on working with schools that listed who to email and when to show up in person. A social worker contributed a checklist of phrases that help kids feel seen without asking them to teach you their pain. We printed the new edition on thicker paper because it will be handled when hands are shaking. The print shop gave us a discount after the manager recognized Emma from the festival program. We mailed packets to three towns we will never visit and called that a good day.

On the third anniversary we held our tradition quietly, with soup that knows the pot well and bread that behaves. The porch lantern clicked on as dusk settled, and the bench carried a folded blanket that fit like memory. Neighbors came with cookies and quick stories, and the door never had to wait long for an answer. At the marked minute we stood together on the step and watched nothing happen, which is the point. Emma slid a new drawing into the hallway frame, a door opening onto steady weather. We toasted with ginger ale and thanked the house for learning its role. Later, before sleep, I wrote one more letter to future Emma and sealed it with a breath I did not owe to fear.

By early spring, Lantern Table had a rhythm that made Tuesdays feel inevitable. New kids found the corner without being told, and regulars greeted them by pulling out chairs. A boy who stuttered when called on in class learned to teach shading with a whisper and a pencil. Emma watched for the breath before his pauses and filled the space with the next step on the page. I stood by the stacks and understood that leadership is just attention practiced out loud. The counselor called it peer modeling and gave her a small pin shaped like a star. She kept it in her pocket instead of on her shirt, because some honors work better when they are carried.

Carla invited us to a community garden day, and Emma said yes before I could translate the ask. We planted thyme in a raised bed that smelled like someone had already cooked dinner. Carla handed Emma the trowel without commentary and matched her pace without turning it into a lesson. They talked about soil and books and whether benches should face east if the street runs north. I watched them agree on small things and felt the future take a seat without pushing a chair. On the walk home Emma suggested pizza with Carla and set a one-hour limit that made sense. We ate on paper plates under the porch lantern and let the conversation stop when it was ready.

I revised the guide again and added a slim companion called Restore that lives after the call. It covers boredom as medicine, sleep as a skill, and rituals that teach houses to behave. We piloted it with three families who asked for steps that felt like furniture, not fireworks. The principal asked for a stack, the clinic printed more, and the treasurer smiled at the unit cost. A pastor requested permission to adapt the scripts, and the answer was yes with footnotes. I wrote our email at the bottom and watched questions arrive like rain that knows the roof. Emma proofread the section on language and changed should to can in four sentences.

In June the nonprofit funded Emma’s idea for a three-day porch art camp, capped at eight kids. She wrote a syllabus with snack breaks, stretching minutes, and a rule that mistakes get chairs too. I set up registrations, background checks for volunteers, and a sign-in sheet that remembered pronouns. On day one, the room found its working hum, and a girl drew a door so open it spilled off the page. Emma praised the spill and showed her how to catch it with a frame drawn after the fact. Parents lingered at pickup and left with resource cards tucked beside damp paintings. At the end she tallied pencils, counted smiles, and donated the stipend back to the bench fund.

A neighborhood thread accused the benches of inviting trouble, and the comments heated like a pan left high. I posted our data and an invite to meet on the porch where opinions have to fit into chairs. Two skeptics came, drank tea, and counted blankets while Beacon took a neutral position on the rug. We reviewed nights, calls, and the one incident that ended with a helpful ride instead of a headline. They left with a copy of Restore and a promise to help on Tuesdays before storms. The thread cooled, a few hearts appeared, and the map gained one more careful dot. I learned again that arguments shrink at doorways because nuance refuses to shout.

In August a storm hit sideways and snapped a branch that tried to occupy the street. A neighbor slipped on wet leaves and twisted an ankle two houses down. We brought the first-aid kit, stabilized what we could, and called for a ride that arrived fast. Emma kept her voice low and her questions simple, matching the calm she wanted to hear back. Beacon lay beside the curb like a sandbag with ears, and the cat watched from the window like a lighthouse. The retired nurse arrived with tape, checked our work, and signed off like a patient teacher. Later we logged the incident and replenished the kit, grateful for small drills that practice being ready.

Emma’s mother started a new job with evening shifts, and our calendar learned a new wobble. The first week we tripped over pickups and forgot which house had the purple folder. Emma’s shoulders rose a notch, and the therapist reminded us that predictability is a language worth speaking. We adjusted with color codes, alarms that dinged politely, and a shared meal that did not move. By Friday the wobble became a rhythm and the folder chose a single hook like it had always known it. We apologized for the mix-ups without turning them into monuments. Emma lowered her shoulders and asked for pancakes, which is our way of signing a truce.

At an art fair, Carla and Emma staffed a table for the nonprofit beside a booth that sold honey. They traded shifts, told the bench story without drama, and sent visitors home with a one-page kit. Between questions, Carla showed Emma how her grandmother stitched quilt bindings that never frayed. Emma listened, practiced the fold, and said the seam felt like a boundary that keeps warmth inside. I watched them share a craft that had nothing to do with crisis and everything to do with care. When a gust lifted the flyers, Beacon held the corner with one paw like a professional. On the ride home, Emma said I like her steadiness, and I nodded like a man who heard the right noun.

The magnet program started with a hallway that smelled like clay, graphite, and ambition. Orientation covered course loads, studio hours, and how to clean a press without losing a finger. Emma found a locker near a window and taped a small lantern print inside the door. The principal spoke quietly about supports and handed parents a card with names instead of slogans. I left before I could hover and trusted the building to do the job it advertised. At home the porch bench waited like a simple promise that did not need a calendar. That night Emma hung her schedule on the fridge, and the grid looked honest and possible.

Her first critique landed on a Tuesday and felt heavier than the folder looked. One student questioned the repetition of lanterns, and the comment grazed her like a low branch. At home we ate pancakes and talked about motif versus rut, and she decided to test a new window. She sketched a series where the source of light is off page, and the rooms still learn to glow. She brought the new set to class, and the conversation turned from theme to choice. Progress looked like a pencil shaving curled at her elbow and a laugh that didn’t check the door. She tacked the strongest drawing over her desk and wrote try again beside it without apology.

A local paper asked for an op-ed, and I wrote about porches as policy using short sentences. I kept names out, put numbers in, and ended with phone lines that answer after midnight. They ran it on a Sunday page between sports and weather, which felt exactly right. A TV producer called and I said no, because some stories survive better without lighting. A neighbor slipped a note into our mailbox that said your words kept me from giving up on Tuesday. I folded the note into the folder that holds other small reasons to keep going. Emma read the op-ed and circled the phrase ordinary courage like a teacher grading a quiz.

As winter returned, we added windbreak panels around the bench and a small sensor that blinked politely. Knitting nights moved to Thursdays, and the hats came in quieter colors that held heat. Emma designed a new sign that said take what helps and leave what doesn’t, which seemed to teach the bin manners. A man left a drawing of a sunrise clipped to the note and wrote thanks for the light in careful print. We laminated it and gave it a spot by the thermos stand where steam names the air. The cat slept through the improvements as if endorsing them by nap. We went to bed smelling faintly of wool and mint, which is a better winter than most.

One evening, the former stepdaughter sent a voice memo laughing about a student who drew thirty doors and called it homework. She said the kid insisted each door had a different welcome, which felt like curriculum and poetry at once. Emma replied with a photo of her new print run and a caption that read I am still choosing light. They planned a classroom swap where each would teach the other’s group the same lesson. I handled the permission slips and bought extra pencils because ambition eats supplies. The swap went smoothly, and each room applauded like they had discovered a secret handshake. Driving home, we agreed that safe rooms learn each other’s dialects quickly.

On the porch after a dusting of snow, Carla asked if I was ready to name what we were doing. I said yes to a word that could sit beside parent without fighting for the chair. We told Emma over pancakes with the same two questions ready to be answered again. She asked for steady Sundays and no surprises on school nights, and we agreed with gratitude. Beacon wagged like a stamp of approval, and the cat ignored us with ceremonial dignity. We put the new word on the calendar in small letters and left the rest of the month blank. The door closed softly when she left that evening, which is how a house says keep going.

In the fourth spring, the city offered a tiny storefront for a shared workshop, and we debated scales. Emma argued for afternoons only, volunteers argued for weekends, and the budget argued for folding tables. We signed a short lease and painted the walls the color of primer that forgives. Lantern Table met there on Tuesdays, benches were built on Saturdays, and math class happened when receipts appeared. A corner held a shelf of Restore guides and a kettle that never boiled angry. People came in needing chairs, not speeches, and left with lists and phone numbers that work. At closing time we swept the floor and thanked the room for trying.

On a summer evening, Emma stood on the porch and watched the lantern come on before she flipped the switch. She said she had learned the timing and liked the half second when light decides aloud. I told her that decision is a muscle, and she laughed like a person who had been training it daily. She packed her bag for a teaching practicum and put the pin-shaped star on the inside pocket. I added a note that said call if the room forgets how to be kind, and she rolled her eyes gently. The cat rubbed her ankle, Beacon touched his nose to her hand, and the door waited without pressure. When she left in the morning, the house held steady, and the bench kept watch the way it always does.

The morning Emma left for her practicum, the house held its breath and then remembered how to exhale. She checked her bag twice, smoothed the pocket with the pin-shaped star, and pressed Beacon’s head like a doorbell. The cat watched from the stairs, pretending indifference the way royalty pretends democracy. I packed her lunch like a dad practicing brevity and slid a note into the side pocket that said go easy on yourself. Carla dropped by with a thermos and a joke about teachers and shoes that do not squeak on linoleum. Emma laughed, took the thermos, and promised to text when the first bell learned her name. When the door closed softly behind her, the house did not creak, which is how I measure progress now.

At the elementary school her mentor greeted her with a clipboard, a warm voice, and a room that already knew where the light came from. Emma started the morning with a simple drawing exercise about doors that feel friendly, not performative. A boy who chewed his hoodie strings asked if doors could be quiet, and she said yes, and showed him how a hinge can whisper. Another student drew a window with a curtain that behaved, and the mentor nodded like she had been waiting to see that curtain for years. They practiced noticing, naming, and acting by tidying the supply table like a neighborhood learns to share a bench. When a fire truck siren drifted through the open window, Emma guided the class to count five blue things without turning safety into theater. By lunch the room’s hum sounded like trust, and the principal stopped by to say the timing of her breathing was perfect.

At the storefront I restocked the guides, adjusted the kettle, and wrote the day’s hours on the window where condensation likes to spell mistakes. A man came in holding a folded flyer like a passport and asked quietly how to help a friend who kept saying everything was fine. We sat at the small table with the tidy corners, and I walked him through the script we keep taped under the glass. He made the call while I stepped away to the inventory shelf, far enough to grant privacy and close enough to be gravity. When he hung up, his shoulders had dropped that half inch you can measure with your own eyes. He took two Restore booklets, said he hadn’t known where to put his hands, and left with something useful to carry. I wrote the interaction in the log, not for statistics but for the feeling of a day that decided to be useful.

Carla arrived with a box of cups and the grin she uses when she’s accomplished something that required phone menus. We labeled shelves while she told me about a student who solved a geometry proof and then taught it back to the class. She said good teaching is hospitality with objectives, and I said good porches are policy with chairs. We talked about compartments, how love doesn’t need to sit where grief used to, and how both deserve proper storage. She asked if the word we chose still fit, and I said it did, especially on Tuesdays when the kettle behaves. The bell chimed, a neighbor waved, and we sold exactly one print to a teenager who liked the courage in the lines. When we locked up, the key turned with that satisfying click that sounds like a boundary keeping its promise.

Emma came home before dusk with chalk on her sleeves and a voice that still had classroom air in it. She told us about a girl who drew a doorknob too high and then lowered it after deciding everyone deserved to reach. We cooked eggs and toast because big days require food that knows its job. Her mentor had written a note about presence, and the word sat on the counter like a postcard from the future. We folded laundry at the table and counted the towels because counting is what you do when words need a rest. She texted a thank-you to the principal and put her phone face down without flinching when it buzzed. Before bed she taped a new sketch to the hallway wire, and the lantern in it breathed like a small, steady animal.

Two nights later, someone scrawled a crude word on the side of the bench and left footprints that looked like confusion trying to sprint. I took a photo for the file, wiped the plank clean, and sanded the grain until the insult lost its foothold. Emma brought out a stencil and repainted the words Open Door Bench with strokes that refused to hurry. Carla set a kettle on low and poured tea for the neighbor who had seen the footprints first. We posted a short note that said vandalism won’t change the job of wood, and the map gained two silent dots by morning. A kid from down the block asked if he could help, and we handed him a brush with a handle sized for his hand. By sunset the bench looked like a lesson, and the lesson looked like community wearing work gloves.

At the college fair the gym buzzed with brochures that promised futures in fonts too cheerful for tuition. Emma spoke to a rep from a teacher-education program who explained how fieldwork starts early if you know the right questions to ask. She asked three of them and received a folder that felt heavier than its paper. We sat in the bleachers to read, and she underlined phrases like culturally responsive and classroom climate as if they were familiar relatives. I filled out a parent contact card and wrote ordinary courage under interests because it didn’t have a box but deserved one. On the ride home we ranked options by proximity, support, and the quality of cafeteria soup. That night she wrote a list on the fridge titled Next Doors, and I pretended not to watch the handwriting steady.

The former stepdaughter visited on a Saturday with a roll of butcher paper and a lesson plan that ended with applause. She and Emma co-taught a circle of kids how to make welcome signs that read like sentences you wouldn’t mind being judged by. They modeled how to negotiate glue sticks and how to share quiet without making it a contest. After cleanup she told us her certification exam date, and we marked it in the calendar with a calm star. We sent her home with a folder of Restore and a bag of markers that do not bleed through. Later she texted a photo of a classroom doorway decorated with paper lanterns that looked like punctuation marks in the right places. I stared at the photo until my eyes watered, which I blamed on the markers even though everyone knew better.

A cold snap rolled in quick and the city asked our storefront to host an overnight warming room for six families. We said yes with conditions that protected staff, kids, and the kind of peace that needs checklists. Volunteers set out cots, we posted rules in simple language, and the kettle took overtime like a pro. Emma managed the art table where paper and crayons kept small hands busy without asking them to explain anything. A social worker handled intakes while Beacon lay by the door greeting arrivals with the diplomacy of a trained napper. By dawn the room smelled like oatmeal and relief, and the logbook recorded nothing dramatic, which is my favorite outcome. We packed the cots, washed the cups, and left the place better than we found it, which is a policy we can keep.

Carla and I began a Sunday routine that looked like a promise without declaring itself a ceremony. We cooked something simple, took a walk, and left the last twenty minutes quiet on purpose. Emma joined when she felt like it and skipped when homework or silence needed the chair more. On one of those Sundays she asked if Carla wanted a key for emergencies, and my eyes did something I pretended was dust. Carla said yes, then no, then yes but only for emergencies, which felt like the right way to enter a room you respect. We labeled the key with a small dot that meant in case, not in general, and slid it onto a separate ring. The door accepted the idea without commentary, which is the only opinion a door should have.

The school year closed with an evening ceremony where students wore shoes that clicked like stage directions. Emma received a small award for service that came with a line about leadership that doesn’t need volume. She walked across the stage with shoulders level and took the paper without apologizing for the space she occupied. I clapped the way you clap for weather finally learning your preference. Afterward we took a photo by the mural of the town’s river, and someone’s flash caught Beacon mid yawn like a celebrity. We went for pie and split the last slice with a precision that would impress a surveyor. On the way home the porch lantern clicked on as if it had been listening for our steps.

The acceptance email arrived on a Wednesday afternoon and disguised itself as routine until the subject line gave up the ruse. Emma read it twice, then a third time aloud, and then sat down like a person who knows chairs were invented for this moment. The program offered a scholarship that covered books, buses, and the kind of materials that smell like a future. We called her mother, looped in the mentor, and let the word congratulations do most of the talking. That evening we walked to the storefront and taped a small copy of the email to the bulletin board where victories share space with schedules. Neighbors signed it in the margins like a yearbook that belonged to all of us and to one person in particular. When we got home, Emma stood on the porch in the half second before the light decided, and then she flipped the switch with a steady hand.

The day after the acceptance, we made a list with boxes you can actually check and taped it beside the fridge calendar. Financial aid appointments, bookstore hours, bus pass forms, and the line that says immunization records all found their little squares. Emma added a rectangle labeled studio orientation and drew a tiny lantern in the corner like a signature. The treasurer stopped by the storefront with sparkling water and a spreadsheet, and we built a tuition envelope that feels like community when you hold it. Neighbors signed a card, the librarian slipped in a gift card for paper, and the band teacher sent a note about patience with photocopiers. We scheduled one more porch clinic and called it the Next Doors Night, because celebration is better when it is also instruction. At the end of the week the map on our site gained a small gold star with her initials, and it looked like hope with receipts.

Move-in day arrived with carts that squeak like optimism and a campus that smells like rain and coffee. Emma’s mother met us by the loading zone, and we made a quiet triangle that worked. Carla parked two blocks away to give space, then appeared with a tool kit and the kind of tape that obeys walls. We carried bins, made the bed, and set the lantern print above the desk where morning light knows where to land. Emma asked for no speeches and high-fives only, and we complied like professionals who have finally learned the brief. Her mother labeled the snack bin, I labeled the chargers, and Carla adjusted the chair until it forgave the floor. When the door tag with her first name went up, the hallway applauded softly in my chest.

Her roommate arrived with a plant, a laugh, and a shelf of novels that smelled like good decisions. They compared schedules, divided drawers, and signed a treaty about lights out that could keep peace between small nations. The RA held a floor meeting about keys, quiet hours, and the emergency exits that turn architecture into kindness. I left a sticky note in the top drawer that simply said call if the room forgets how to be gentle. Emma walked us to the elevator and pressed the button like the captain of a ship telling the tide to behave. The door closed with the soft confidence of a hinge that has been rehearsed. I drove home on muscle memory while Beacon kept my seat warm in theory and the bench held the porch like a vow.