While the Battle Raged in Europe, Germans Sang ‘Silent Night’ in Kansas: The Untold Story of America’s POW Farm Program

How 370,000 German Soldiers Came to Discover the American Heartland — And Why Hundreds Never Wanted to Leave

September 14, 1944. On a dirt road near Concordia, Kansas, a convoy of olive drab Army trucks rolled through golden wheat fields. In the back of one truck sat 23 German prisoners of war, freshly arrived from Europe. Eleven weeks earlier, they had surrendered in Normandy. Now, they watched with disbelief as American children waved to them from front porches, and white farmhouses dotted a horizon that looked like a postcard.

“Das kann nicht sein,” muttered Hans Görtz, a former German grenadier, as he stared out the canvas flaps. This can’t be real.

But it was.

Between 1943 and 1946, more than 370,000 German POWs were held across the United States. While the largest camps were in the South, tens of thousands of prisoners were sent into rural America to solve an agricultural crisis that threatened the Allied food supply.

The War Behind the War

In 1944, America’s farms faced a labor emergency. Over 12 million American men were in uniform. Another 18 million worked in war industries. That left farms without hands to bring in critical crops like wheat, sugar beets, cotton, and potatoes.

Faced with rotting harvests and empty fields, the U.S. government turned to an unexpected solution: German prisoners of war. Held in more than 500 base camps and 700 smaller work detachments across 46 states, German POWs became a crucial labor force.

The arrangement adhered to the Geneva Convention of 1929, which allowed POWs to work as long as they were treated humanely, paid, and not used in war industries.

Camp Concordia: Barbed Wire in the Heartland

Camp Concordia in Kansas was one of the more typical medium-sized camps, holding around 4,000 prisoners at its peak. Surrounded by a simple fence and four guard towers, it looked more like a fairground than a prison.

Prisoners lived in tar-paper barracks, played soccer, attended classes in English and American history, and even published a camp newspaper. But the real education came when they left the fence.

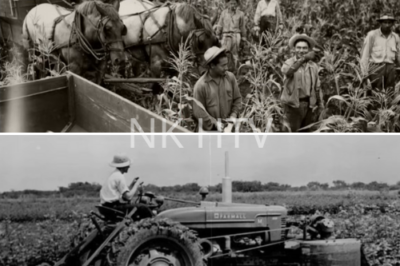

Prisoners were trucked out to work in fields across the Midwest: Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Wisconsin, the Dakotas. They harvested sugar beets, picked potatoes, milked cows, and operated American farm machinery.

“They looked around and saw something they didn’t expect,” recalled James Henderson, a former Camp Concordia guard. “They saw abundance. Peace. And regular people who treated them like human beings.”

From Enemies to Essential Workers

Farmers like Robert Hoffman of Clay County, Kansas, were skeptical at first. His son was fighting in Europe. Now, the government was sending him Germans to bring in his sugar beet crop.

But when the trucks arrived and the prisoners climbed down, most of them little more than boys in patched uniforms, something changed.

“Anybody here know sugar beets?” Hoffman asked in rough German.

Three hands went up.

The prisoners were supposed to remain under supervision, separated from civilians, and returned to the camp each night. In practice, rules were quickly bent. Guards were often older men or recovering soldiers, and after a few days, they parked under a tree with a sandwich and let the Germans work.

The Meal That Changed Everything

October 11, 1944. After a cold rain, Robert Hoffman did something technically against War Department rules. He invited his prisoners inside.

Elizabeth Hoffman served chicken and dumplings, green beans, biscuits, butter, and apple pie. One of the Germans had tears in his eyes.

“Hans told us it was the first time he’d sat at a family table in three years,” said Martha Hoffman Klene, then a teenager. “It reminded him of home, before the war.”

This moment would be replicated across thousands of farms. Families shared meals. Children played with the young prisoners. Germans taught farm kids how to sing “Stille Nacht” — Silent Night.

By Christmas 1944, as the Battle of the Bulge raged in Belgium, German prisoners across Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, and Minnesota were eating Christmas dinners with American families.

Not Just Work — A Cultural Transformation

The work program wasn’t just an economic necessity. It became the most successful prisoner re-education program in American history.

“You can show a man a film about democracy,” said historian Ron Robin, “but when he eats at a farmer’s table and watches how Americans live and speak freely, that’s what teaches him.”

Letters home reflect this shift. In September 1944, Hans Görtz wrote:

“We are treated correctly according to the Geneva rules.”

By February 1945:

“I begin to understand why we lost. Not just machines. It is their belief that a man can rise through work. That even the daughter of a farmer may study and own land.”

Some prisoners remained committed Nazis. Conflicts erupted. In November 1944, a suspected anti-Nazi was beaten by fellow prisoners. American authorities began segregating camps to prevent violence.

But many POWs, especially those who worked directly with American families, softened. The ideology melted. Humanity returned.

A Reluctance to Leave

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, most POWs expected to be sent home. But under the Geneva Convention, the U.S. could retain them for labor until a formal peace treaty. Many stayed through 1946, helping rebuild American agriculture.

The longer they stayed, the deeper the bonds grew.

Robert Hoffman tried to sponsor Hans Görtz to immigrate permanently. Görtz wrote:

“I wish to farm here. I wish to become American.”

But immigration quotas were strict. Only 19 POWs are known to have had their applications approved before 1950.

Görtz returned to Germany in 1946. His family farm near Münster had been damaged but not destroyed. He rebuilt it, married, and had four children. He corresponded with the Hoffmans for 40 years.

The Legacy

In 1976, Camp Concordia held a reunion. Seven former prisoners returned. Over 400 locals came. There were handshakes, hugs, and more than a few tears.

“You treated us as men,” said Friedrich Müller, a former POW. “You showed us a better way. We carried that home. And it helped us build a better Germany.”

The impact of the POW labor program went beyond economics. It gave tens of thousands of young German men their first real taste of freedom, fairness, and democracy.

They didn’t all become Americans. But they carried American values back with them.

In a very real sense, America planted democracy not with speeches, but with meals, work, and kindness in the heartland.

Final Thoughts

While Allied forces stormed Europe, German POWs pulled weeds in Nebraska, milked cows in Wisconsin, and fixed tractors in Iowa.

They arrived as enemies. Many left as friends.

They came expecting punishment and found pie. They brought memories of battlefields and left with memories of barn dances.

The legacy of that era is still alive in letters, photographs, and the quiet memory of families who took a risk and welcomed the enemy to dinner.

Not all of them got to stay.

But the ones who didn’t?

They took a piece of America home with them.

News

ch1 POWs Sang “Silent Night” in Kansas — While the Battle of the Bulge Raged in Europe

While the Battle Raged in Europe, Germans Sang ‘Silent Night’ in Kansas: The Untold Story of America’s POW Farm Program…

CH1(nk)The U.S. Army Was Humiliated in Its First Real Test. British Officers Quietly Wondered If America Was Ready for This War at All. Then One General Looked at a Retreat and Saw the One Detail Everyone Else Missed. What He Did Next Turned a Collapse Into a 304-Mile Counterattack. This Is the Untold Story of How a Broken Army Learned to Move Faster Than Its Enemy Could Think.

At dawn on February 20, 1943, the mountains of central Tunisia shook with the sound of artillery. The air over…

CH1(nk)One Iowa Farmer Made 40 German Prisoners Go Silent. They Thought Americans Were Lazy. What They Saw That Afternoon Proved Why Their Side Never Stood a Chance. This Forgotten Story Explains How a Single Machine Helped Win a Global War.

On a blazing July afternoon in 1944, a group of German prisoners of war stood in an Iowa wheat field…

(nk)The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Truth

Powered by GliaStudios The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed…

The 7-year-old boy in the wheelchair tried to hold back his tears while his stepmother humiliated him without mercy.

For two years, the Montes de Oca mansion had lived in silence—not from the absence of people, but from the…

THE MILLIONAIRE’S BABY CRIED WHEN HE SAW THE MAID — HIS FIRST WORDS SHATTERED EVERYONE

The Little Boy Who Called the Maid “Mom” The crystal glasses still vibrated when silence fell across the grand hall….

End of content

No more pages to load