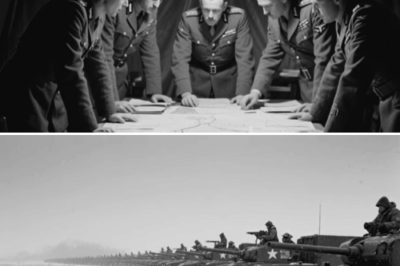

On the morning of December 18, 1944, the numbers said the war in Europe was almost over. The experts said the enemy’s army was broken. The maps in the headquarters made it look like victory was a matter of time and logistics.

But on a frozen bridge in Belgium, none of that mattered.

There, a 19-year-old American sergeant named Francis Currey was staring at a nightmare that wasn’t supposed to exist anymore: a massive German heavy tank rolling toward him through the fog, supported by some of the most hardened infantry in the enemy’s army.

Currey weighed about 130 pounds. He had no tanks behind him, no aircraft overhead, and no reserves on call. His squad was badly outnumbered, pinned down, and nearly out of options. In front of him was a steel giant that could shrug off most of the weapons he had.

Every handbook said his situation was hopeless.

Currey wasn’t thinking about handbooks.

He was thinking like a farm kid who’d grown up fixing what was in front of him, with whatever tools he had, because nobody else was coming.

In the next few hours, this quiet orphan from Indiana would turn a “routine guard duty” into one of the most astonishing small-unit stands of the Battle of the Bulge. He would knock out vehicles, hold off elite troops, save his trapped comrades, and keep a vital bridge out of enemy hands — often completely alone.

And then, when the war was over, he would go home and slip quietly back into ordinary life, the kind of man you’d walk past in a waiting room without ever guessing what he’d done.

This is his story.

The “Quiet Sector” That Was a Trap

In December 1944, Currey’s unit — Company K, 120th Infantry Regiment — was sent to what was supposed to be a calm stretch of the line near the Belgian town of Malmedy. Soldiers called it the “ghost front.” It was where battered units were sent to rest and new ones were sent to learn.

The snow made everything look peaceful. The pine forests were still. The front felt distant.

It was an illusion.

Out in those woods, hidden under a blanket of fog and bad weather, the enemy was assembling a last, desperate gamble: a massive surprise offensive that would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. Over 200,000 men and hundreds of armored vehicles were moving at night, under strict radio silence, relying on low clouds to hide them from Allied aircraft.

Currey and his squad were told to secure a bridge over a small river near an industrial building — an assignment that sounded simple. Guard the crossing. Watch the road. Stay alert.

They had no idea they were standing directly in the path of a spearhead from one of the most feared armored formations in the enemy’s arsenal.

As the temperature plunged and the ground froze solid, the Americans tried to dig in. The frost was so hard that digging a foxhole was like trying to carve concrete. Their boots soaked through. Their breath turned to ice. They shivered in thin winter clothing that was never meant for this kind of cold.

Currey checked his men. He didn’t brag or bluff. He just watched. He watched the treeline. He watched the fog. And somewhere deep down, the same sense he’d developed on the farm — that feeling when the birds go silent and you know a storm isn’t coming, it’s already here — started to kick in.

He was right.

From Orphan to “Weakling” to Squad Leader

To understand what Currey did on that bridge, you have to understand where he came from.

Born in 1925, he lost his parents young. By the time most kids were worrying about school or games, he was worrying about where he would live and how he would work. He bounced around relatives and foster homes before ending up on a farm in Indiana.

On a Depression-era farm, an orphan wasn’t pampered. He was a worker.

Currey’s childhood was long days of cold mornings, heavy lifting, and hard chores: pitching hay, fixing fences, wrestling with broken machinery. No one cared how tired he was. No one was going to “save” him from the work. If something was broken, you figured out how to fix it. If a job was too heavy, you didn’t complain — you found a lever, a better angle, a way to make it possible.

It wasn’t military training. It was something deeper: an instinct for problem-solving under pressure, and a quiet toughness that didn’t need an audience.

When the war came, Currey tried to enlist at 17 and was turned away as too small. He didn’t sulk. He came back at 18, having forced his weight up just enough to make the minimum. The army saw a skinny kid and assumed he was better suited for a soft job. They didn’t see the calloused hands and sharp eyes of a farm worker.

He ended up in the infantry anyway.

By the time he reached Europe in mid-1944, Currey had gained something far more important than muscle: the respect of his squad. Under fire, he stayed calm. When orders got confusing, he focused on the task in front of him. He picked up the heavier weapons no one else wanted to deal with — the Browning Automatic Rifle, the bazooka — and learned their quirks the way he’d once learned the quirks of old farm equipment.

By December, the “weakling” was a sergeant, in charge of other men.

Nothing in that journey, though, could fully prepare him for what stepped out of the fog on December 18.

A Tank, a Ditch, and a Decision

The first sign was not visual. It was physical.

Currey and his squad felt a vibration in their chests before they heard the sound: a deep, grinding rumble that made the icy branches tremble. Then came the squeal of tracks and the clatter of metal on frozen ground.

Currey eased up to peer out from his position near the bridge.

Out of the mist, a massive tank rolled into view, painted in winter camouflage, its long gun barrel sweeping slowly across the street like a searching finger. Behind it, enemy infantry moved in the snow — disciplined, methodical, and very much at home in combat.

These weren’t raw recruits. They were veterans from an elite armored division.

Currey’s squad was outnumbered and outgunned. They had rifles, a machine gun, and a few anti-tank weapons. They did not have anything that looked, on paper, like enough.

And the tank’s gun was now swinging toward the building where several of his fellow soldiers were sheltering.

Doctrine said you pull back when you’re facing armor that strong with no real support. You live to fight another day. You fall back to stronger positions.

Currey looked at the bridge. He thought about what would happen if those tanks crossed it — how they could roll deeper into the American rear, reaching depots and fuel dumps that kept the whole front alive.

Then he looked at the bazooka lying in the snow beside him.

He didn’t see a hopeless situation. He saw a problem to solve.

He stood up in his snowy ditch, aimed, and fired.

The rocket didn’t blow the tank apart in a fireball. Instead, it slammed against the thick armor with a brutal clang and shattered. But it stripped away the tank’s external sights and kicked up a blast that effectively blinded the crew inside.

Suddenly that steel giant was stumbling in the dark.

Shells from the tank crashed into nearby walls. The concussion hammered Currey and buried him in dust and snow. Most people would have stayed down.

Currey checked his weapon, realized he was out of rockets — and immediately started thinking about how to get more.

One Soldier, Three Roles, and a Town That Refused to Fall

Across the road, Currey spotted an abandoned American halftrack loaded with supplies. If there were more rockets anywhere nearby, it would be there.

There was one problem: the ground between his position and that vehicle was a shooting gallery. Enemy machine guns had it zeroed in, and tracer rounds were stitching the snow.

He went anyway.

He sprinted through the open, dove behind the halftrack, ripped open an ammunition crate with numb hands, and reloaded his bazooka. When the heavy tank pulled back, lighter tanks and infantry moved in.

Currey knocked a tank out of action, then switched weapons and opened up on the infantry with a Browning Automatic Rifle. For several frantic minutes, he became his own fire team — firing rockets, then machine-gun bursts, then changing positions and doing it again.

From the enemy’s point of view, it looked like a coordinated defense with multiple gunners.

In reality, it was one exhausted 19-year-old sprinting from position to position, working through the cold and pain on sheer determination.

He was hit by blasts, battered by debris, and shaken by near misses. Each time, he got back up, checked what still worked — legs, hands, weapons — and went back to work.

When the situation worsened, he climbed into another halftrack and brought a .50-caliber machine gun into the fight, using its heavy fire to pin enemy troops and cover the escape of five wounded Americans trapped in the factory building.

He shouted for them to move while he held the line.

Finally, when the big gun jammed and his heavier weapons ran dry, Currey fell back into the ruined structure with only his rifle and a handful of grenades. Enemy soldiers stalked the shattered rooms, convinced they were hunting a full team.

Currey turned the broken building into a maze, using his knowledge of the layout to outmaneuver them. He fired, disappeared, reappeared elsewhere, and kept them off balance. At one point, a sniper’s bullet hit the rim of his helmet hard enough to knock him unconscious and send the helmet flying.

The enemy assumed he was dead.

He wasn’t.

Bruised, concussed, and barely able to move, Currey woke up under debris, realized the fight wasn’t over, and dragged himself back into the battle.

The Shot That Broke the Advance

By now, Currey’s body was at its limits. He was soaked, freezing, and battered, with only a few rounds of ammunition left. Enemy forces were regrouping to push across the bridge and exploit the gap.

He could not stop the tanks with a rifle. But tanks, he knew, depended on fuel and leadership.

Crawling through a drainage ditch behind enemy lines, he worked his way close enough to see a command vehicle and a tank carrying external fuel drums. From his cold, muddy position, he took careful aim — not at a person, but at those fuel containers.

A few well-placed shots later, the tank was suddenly engulfed in flame. In the chaos, the enemy commander’s communications were disrupted. To the enemy, it looked and felt like a larger American force had struck from the rear.

Confusion turned to fear. Orders turned into shouts. Vehicles backed up. Infantry began to pull away, unsure of how big the threat really was.

The advance on the bridge collapsed.

Currey stayed in his ditch until his last rounds were gone, firing into the smoke to encourage the retreat. Then he simply ran out of ammunition — and strength. The cold finally began to win. He lay there as snow started to cover him, drifting between consciousness and something darker.

He had done what he set out to do: the bridge was still in American hands.

Hours later, the men he’d saved came back looking for him.

They found him half-buried in snow, barely alive, and dragged him out of that ditch. He woke up in a hospital bed in England, battered and frostbitten, but alive.

The Medal, the Stadium, and the Quiet Life

The war ended. The enemy surrendered. Those heavy tanks that once seemed unstoppable ended up as scrap metal or museum pieces.

In July 1945, Currey was ordered to report to a stadium in Germany. He didn’t know why. He stood in formation, looking like any other thin, worn-out young soldier.

Then a senior general read out a citation for actions near Malmedy: holding a bridge under overwhelming attack, disabling vehicles, rescuing trapped comrades, and forcing a much larger enemy force to withdraw.

The citation ended with the words “above and beyond the call of duty.”

The entire stadium fell silent as the list of actions rolled on — the stand at the bridge, the destroyed vehicles, the lives saved. Then the general stepped forward and placed a blue ribbon around Currey’s neck.

He had just been awarded the Medal of Honor.

In the famous photo from that day, Currey doesn’t look like an action hero. He looks like what he always was: a slightly bewildered young man who had done what he felt needed to be done.

After the war, he didn’t chase fame. He went home, took a job working with veterans, and spent decades quietly helping others navigate the struggles that followed them back from battle. Many of the people who sat across from his desk never knew they were talking to one of the most decorated heroes of the Battle of the Bulge.

He gardened. He fixed things. He lived simply.

When he passed away in 2019 at age 94, he was the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from that brutal winter campaign.

What Francis Currey Really Proved

We live in a world that often equates strength with size, volume, or spotlight. We imagine heroes as larger-than-life figures, impossibly confident and immune to fear.

Francis Currey was none of those things.

He was a quiet orphan who did hard work without complaint. A kid who barely made the weight requirement. A young man who treated a battlefield like a broken tractor: a dangerous, terrifying, confusing problem — but still a problem to be solved.

On that frozen bridge in Belgium, the enemy brought armor, numbers, and momentum.

Currey brought something they couldn’t measure on a map: grit.

Not the loud kind, but the kind that gets back up after the blast, that crawls when walking isn’t possible, that keeps thinking when panic would be understandable.

His story reminds us that history is not just shaped by famous names on posters and statues. It’s shaped, again and again, by people who never expected to be heroes — farm boys, factory workers, clerks, and kids who learned early that nobody was coming to rescue them, so they’d better learn to stand their ground.

On December 18, 1944, everything said Francis Currey was outmatched.

He refused to accept the math.

And because one skinny nineteen-year-old refused to give up a bridge, an entire armored thrust was thrown off balance — and the story of the Battle of the Bulge was quietly, powerfully rewritten by a boy who went back home and planted tomatoes.

News

(nk)Lily and Max: An Inspirational Story of Love, Courage, and Family Bonds

Last Updated on September 8, 2025 by Grayson Elwood Life has a way of testing us when we least expect it….

ch1(nk)The Phone Call That Changed the Battle of the Bulge

One Winter Phone Call That Saved an Army.The Supreme Commander Didn’t Believe It Could Be Done.A “Crazy” Promise Turned Into…

(nk)During dinner, my daughter quietly slipped a folded note in front of me. “Pretend You’re Sick And Get Out Of Here,” it read. I didn’t understand — but something in her eyes made me trust her. So I followed her instructions and walked out. Ten minutes later… I finally realized why she warned me.

When I opened that small, crumpled piece of paper, I never imagined those five words, scribbled in my daughter’s familiar…

(nk)They Spilled Coffee on a Black Girl, Not Knowing She Was a Billionaire’s Adopted Daughter

A Cup of Justice The wind in Manhattan bit through Jonathan Hail’s overcoat as he carried Anna across 81st and…

At Our Divorce Hearing, My Husband Mocked (nk)Me in Front of His Mistress. But When the Judge Read My Sealed Evidence, Everything They Planned Fell Apart

Last Updated on December 1, 2025 by Grayson Elwood The morning of our divorce hearing, the air inside the courthouse felt…

(nk)“You know what? I think we can fix that,” I said as I stood up. I turned to the shop owner.

“You know what? I think we can fix that,” I said as I stood up. I turned to the shop…

End of content

No more pages to load