At dawn on February 20, 1943, the mountains of central Tunisia shook with the sound of artillery. The air over the Kasserine Pass was thick with dust, smoke, and confusion. American units that had arrived in North Africa full of confidence were now falling back faster than their commanders could even locate them on a map.

By mid-morning, the messages flowing into headquarters didn’t sound like normal battle reports anymore. They sounded like alarm bells.

“Unit overrun.”

“Position abandoned.”

“Men scattered.”

In less than a day, the U.S. Army had suffered a blow so serious that hardened British veterans—men who had already survived three brutal years of war—whispered to each other that maybe, just maybe, America wasn’t ready for this kind of fight.

At Kasserine Pass, the numbers told a harsh story. Over 2,500 Americans killed, wounded, or missing. Nearly 200 vehicles destroyed or left behind—some tanks with their guns still clean, never fired in combat. Enemy armor came through the pass at a pace nearly a third faster than American planners had predicted, sweeping aside roadblocks and hasty defenses as if they were nothing more than cardboard.

Some American units broke within minutes. Others tried to hold but lacked ammunition, radios, or clear orders. What had been planned as a controlled defensive stand dissolved into the worst defeat in the modern history of the U.S. Army.

And yet, in the middle of that disaster, one man was already building the comeback.

A Green Army Meets a Relentless Opponent

In early 1943, the American Army in North Africa was brand new to large-scale ground combat.

Fewer than 20% of its officers had ever heard an enemy round whistle overhead. Over 70% of its enlisted soldiers had never fired a shot in anger. Most had trained on flat American fields, not in rocky mountains and twisting desert passes.

The enemy they were facing was the exact opposite.

The armored formations driving into Kasserine were filled with veterans who had fought in Poland, France, Greece, and across North Africa. They knew how to use terrain. They knew how to coordinate artillery, tanks, and infantry. They knew how to turn speed into a weapon.

The imbalance was brutal.

A 19-year-old American private from the Midwest later described seeing his first enemy tank crest a ridge. First came the deep rumble, then the dust cloud, then the flash of the gun and the realization that someone was actually shooting at him. He froze for a heartbeat, then stepped back, then ran.

It wasn’t cowardice. It was raw shock.

That same shock rippled across the pass. Artillery crews abandoned their guns. Truck drivers turned their vehicles around and floored the gas. Whole units pulled back not because they were ordered to, but because they had no idea where anyone else was.

Communication lines were cut in the first hour. Radios failed or were misused. Some commanders thought the enemy was still miles away when enemy armor was already rolling into their positions.

Observers from allied units wrote, in almost clinical language, that the Americans were “learning the lessons of war the hard way.”

They were right. But they were only seeing half the story.

“We Weren’t Beaten by Tanks. We Were Beaten by Confusion.”

On paper, American equipment didn’t look hopeless.

The U.S. had modern medium tanks like the M4 Sherman. It had respectable artillery. It had trucks, jeeps, and aircraft in quantities the enemy could only dream of.

But battles are not fought on paper.

In Tunisia’s rocky, uneven terrain, American tanks threw tracks more often than expected. Maintenance teams had never dealt with this type of environment. Some early-model tanks had guns fixed in the hull, forcing the entire vehicle to pivot just to aim, while enemy tanks could traverse their turrets freely and faster.

Maps were outdated. Signal procedures were slow and sloppy. When enemy artillery cut a key phone line along a main road, nearly half of a major American formation lost contact with headquarters. Radio operators, under stress and poorly trained, sent long, unclear messages that clogged the air.

One American officer later summed it up with painful honesty: “We weren’t beaten by tanks. We were beaten by confusion.”

To the opposing side, this seemed to confirm what they already believed. Intelligence reports described American soldiers as “soft” and “undisciplined,” brave but clumsy, equipped but not truly dangerous.

For a brief moment at Kasserine, that assessment wasn’t entirely wrong.

But there was something hiding inside that confusion—buried in the chaos of the retreat—that almost no one noticed.

Almost.

The Man Who Looked at a Retreat and Saw a Measurement

In the days after Kasserine, one officer pored over the raw reports: fuel logs, movement times, retreat distances, traffic patterns on the roads behind the front.

His name was George S. Patton.

Where others saw only arrows pointing backward on a map, Patton saw data.

As truck columns fled the pass under fire, they had been moving at speeds between 18 and 25 miles per hour over rough ground. These were not sleek sports cars or light scout vehicles—these were fully loaded military trucks, many of them driven by young men who had never imagined they’d be doing this under enemy pressure.

On the other side, enemy armored columns in that sector averaged closer to 12–14 miles per hour over similar terrain.

To almost everyone, the retreat was a humiliation. To Patton, it was proof.

If American vehicles, with no plan and no coordination, could move that far, that fast while running away, what could they do with a plan? With discipline? With leadership that understood speed as a weapon, not an accident?

He didn’t just see a broken line. He saw a hidden advantage, waiting to be turned around.

So when Patton arrived to take charge of the battered formations in early March, he didn’t speak like a man preparing to dig in and hide. He looked at the maps, at the jagged line of the recent retreat, and said:

“This ends now.”

Turning Humiliation Into High-Speed Discipline

What followed hardly looked like heroics. It looked like a crackdown.

Patton toured camps, headquarters, and front-line positions like a storm.

Helmets on.

Sidearms carried.

Tents lined up.

Vehicles cleaned, inspected, and refueled.

Shaving required every morning.

To some, it felt petty—like a general obsessing over appearances after a defeat. But under the surface, it was all flowing toward one purpose: speed.

Patton understood something few others did at the time: you cannot move fast in combat if the basics are sloppy. The same army that had sprinted backward in disorder now had to learn what it felt like to move forward in organized, controlled aggression.

He cut the time it took infantry to climb into trucks. He pushed gunners to reload faster. He drilled tank crews to mount and dismount their vehicles until they could do it almost instinctively. He rewrote radio procedures so messages were short, clear, and fast.

He reworked how traffic moved. Instead of long, slow columns clogging roads, he ordered tighter, more focused streams of vehicles, with fuel and ammunition trucks pushed forward instead of lagging behind. Maintenance teams became mobile “pit crews,” swapping out engines and fixing tracks at incredible speeds.

It wasn’t glamorous. It was mechanical.

And it was exactly what this army needed.

Beneath the harsh language and strict rules, Patton was telling his soldiers something important:

You are not slow. You are not weak. You are disorganized. Fix that, and you can be faster than anyone you face.

Three Days That Stunned the Desert

In mid-March, before dawn, engines began to growl across miles of desert. Trucks, tanks, and support vehicles lined up not to fall back this time—but to surge forward.

Patton’s counterattack started in the dark and didn’t move like the army that had been routed at Kasserine. It moved like a shock wave.

On day one, the American advance covered roughly 90 miles through rocky passes, dried riverbeds, and rough tracks. On day two, it didn’t slow—it accelerated, passing 100 miles. On day three, it pushed past that again.

Over three days, the battered force that had once stumbled backward now drove forward more than 300 miles.

Enemy scouts reported American vehicles appearing in places they weren’t supposed to reach for another day or two, based on traditional movement calculations. One report back to higher headquarters simply stated that the Americans were advancing “too quickly to be plotted” on normal timetables.

Patton had taken the raw speed revealed in the retreat and turned it into controlled momentum.

Fuel trucks moved inside the columns, refueling on the go. Repair teams worked beside the front lines, swapping parts instead of dragging vehicles to rear workshops. Infantry rode in trucks that outran armored units accustomed to setting the pace.

For the first time in the desert war, the enemy wasn’t just under fire. They were being outrun.

The Real Battle: Trucks, Fuel, and Time

What made this possible wasn’t just courage, and it wasn’t magic.

It was logistics.

By 1943, the American force in North Africa was fully motorized. If it moved, it moved on wheels or tracks. No horse-drawn wagons. No marching columns trying to keep up with tanks.

That mattered more than most people realized.

A traditional infantry formation on foot could cover maybe 12–15 miles a day under good conditions. A motorized formation could cover four to six times that distance. And when your opponent is tied to slower systems—whether it’s horses, limited trucks, or fuel shortages—speed becomes more deadly than any single weapon.

On top of that, American equipment was built with interchangeable parts and simple, rugged designs. Engines were mounted to be swapped quickly. Tracks, tires, and mechanical components were standardized across huge fleets of vehicles. If something broke, the answer wasn’t “nurse it along.” The answer was “swap it and keep moving.”

Behind it all stood something even bigger: an industrial economy capable of sending spare engines, tires, and fuel across an ocean in quantities that looked almost unreal to anyone used to tight rationing.

While the opposing side measured fuel by the barrel and prayed their convoys wouldn’t be sunk on the way across the sea, Patton’s men had entire depots stacked high with supplies. That surplus wasn’t waste. It was freedom—the freedom to move fast, make mistakes, and still keep going.

From Desert Disaster to Blueprint for Victory

The three-day, 304-mile counterattack in Tunisia didn’t destroy every enemy unit in front of it. But it did something more important.

It took the initiative away.

After Kasserine, the opposing commanders had believed they were in control of the tempo, choosing when and where to hit. After Patton’s counterstroke, they found themselves constantly reacting, burning precious fuel just to avoid encirclement, shifting units back and forth to meet threats that seemed to appear earlier than they should have.

They were no longer choosing the battlefield. The battlefield was choosing them.

Within weeks, the North African campaign swung decisively. By May 1943, hundreds of thousands of enemy troops laid down their weapons in Tunisia. The road to the next phase of the war—Sicily, then Italy, then eventually Normandy—was open.

But the most important transformation wasn’t on a map. It was inside the U.S. Army itself.

The force that had arrived in North Africa green and disorganized left as something fundamentally different: hardened, coordinated, and comfortable with movement at a tempo that would define the rest of the war.

The young private who had run at Kasserine now trusted his truck, his crew, and his training. The officers who had once lost track of their own units now thought in terms of miles per day, fuel per mile, and how to keep pressure on an enemy without ever letting the pace slow.

Patton captured that change in a single line in his diary: after the counterattack, he wrote, his men were “not afraid to move. They were afraid to stop.”

Why This Story Still Matters

It’s easy to look back at history and focus only on the moments of triumph: the successful landings, the flags raised, the victory parades.

What happened at Kasserine—and what happened just weeks later in that 304-mile counterattack—reminds us that real turning points often start with failure.

The U.S. Army’s worst defeat in the desert became the laboratory where it discovered its greatest strength: the ability to learn fast, to adapt under pressure, and to turn raw industrial power into controlled speed on the battlefield.

One general saw a retreat and read it like a math problem.

He saw not just what had gone wrong, but what might be possible.

Out of that insight came a new way of fighting—one built not on perfection, but on motion, logistics, and relentless tempo. It was born in the dust of Tunisia, refined in Sicily and Italy, and unleashed in full on the roads of France and Germany.

In the end, this story isn’t just about one general or one battle. It’s about an army that grew up in a hurry—and about how sometimes, the most important victories begin on the worst days, when someone looks at chaos and sees not an ending, but a starting line.

News

A Billionaire Freezes in Shock After Seeing His Mother Leaning on a Homeless Man — What Happens Next Changes Everything

Alejandro Ruiz stepped out of the glass skyscraper in the upscale Salamanca district, fresh from closing a €30 million deal….

Her husband threw her out for being infertile—and then a single father CEO asked: “Come with me.”

Snow fell heavily that December afternoon, thick flakes muffling the city into an eerie silence. Clara Benítez sat at a…

“She’s nobody,” said the CEO’s fiancée, but the children shouted, “She’s our mom!”

For two years, the grand Montes de Oca mansion had been drenched in silence. Not peaceful, comforting silence—but the heavy,…

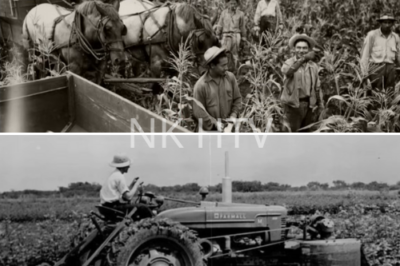

ch1 From Enemies to Farmhands — How German POWs Found Humanity in Kansas Fields

While the Battle Raged in Europe, Germans Sang ‘Silent Night’ in Kansas: The Untold Story of America’s POW Farm Program…

ch1 POWs Sang “Silent Night” in Kansas — While the Battle of the Bulge Raged in Europe

While the Battle Raged in Europe, Germans Sang ‘Silent Night’ in Kansas: The Untold Story of America’s POW Farm Program…

CH1(nk)One Iowa Farmer Made 40 German Prisoners Go Silent. They Thought Americans Were Lazy. What They Saw That Afternoon Proved Why Their Side Never Stood a Chance. This Forgotten Story Explains How a Single Machine Helped Win a Global War.

On a blazing July afternoon in 1944, a group of German prisoners of war stood in an Iowa wheat field…

End of content

No more pages to load